Calais After the Jungle

Interview with Calais Migrant Solidarity

by Corporate Watch

20 June 2019 (original posts in English and French)

In 2016, the northern French port town of Calais was all over the TV screens, as an army of gendarmes and CRS riot police evicted the “Jungle”i – a largely self-built refugee camp where about six thousand exiles from the world’s war zones lived in sight of the razor-wire border fences. But Calais’ refugee story goes back much further, and it’s not over yet. Hundreds of refugees are still gathered around the main channel crossing point, living in even more miserable and precarious conditions now that the big jungle is gone. To get a snapshot of the current situation, Corporate Watch talked to friends from Calais Migrant Solidarity, a network that has been active alongside migrants in Calais since 2009.

Corporate Watch: How many people are still trying to cross the border at Calais? Where do they come from?

Calais Migrant Solidarity: In Calais itself, maybe around five hundred people. It fluctuates a lot, so perhaps between three hundred and six hundred people at any time. But then there are also hundreds more people further along the coast at Dunkerques, and all the way towards Belgium.

In Calais the nationalities of people follow the same patterns – we’re talking about people from war zones and dictatorships, where those countries have a historical connection to British colonialism. So people may speak English, or have family connections, or may have grown up with some idea of the UK as a safe haven and a beacon of democracy. Many Afghans, Iraqis, Iranians, Kurds, Eritreans, Sudanese, and also a few others now from as far as Nigeria, Chad and other places.

There are not so many children and women now, and those who do turn up are often sheltered by charities. There are more families in Dunkerques, where there is a more sympathetic mayor who provides a gym building where vulnerable people are allowed to stay. There are maybe three hundred people living inside that, including at least thirty families (about one hundred people), and maybe around one hundred unaccompanied minors. Also, there are around another three hundred people living in tents near the gym, which are more or less tolerated by the authorities. A lot of these are Kurdish people from all countries – Turkey, Syria, Iran and Iraq. Then there are also more informal Pakistani and Afghani settlements in the woods outside Dunkerques, which are treated much worse and attacked on a daily basis by the police, as in Calais.

CW: And do people still manage to cross?

CMS: Yes, of course. But the massive securitization in recent years has meant that people need to travel farther and take ever greater risks.

CW: Hence the recent boat crossings that have made the headlines?

CMS: They can’t make a fence in the middle of the sea. People always find ways around fences, under or over, and crossing the channel is one of the latest and most visible ways people have been trying. It is extremely dangerous, particularly for the high traffic. But the UK is actually visible from Calais. People have traveled thousands of miles to get here, often risking their lives many times—then they see the cliffs of Dover in the distance, and they’re not going to stop.

The boats are so far mainly organized by smugglers who charge a lot of money for spaces. But there have also been some individuals trying to cross on makeshift rafts, like the guy without an engine who was washed as far as the Netherlands. People like that aren’t even able to buy a life jacket—there have been reported cases where shops refused to sell lifejackets to people, asked to see their papers, and threatened to call the police. Of course this doesn’t hurt the organized smugglers, but it makes the attempted crossing even more hazardous for individuals trying to make it themselves.

CW: So what is daily life like now for people trying to cross the border in Calais?

CMS: Basically, the authorities have pretty much succeeded now in clearing people out of the town center, and also stopping them from creating any stable settlement like the old jungle. So people are scattered and hidden in very precarious camps outside of the town. People still talk about the “jungles,” but that means just a few tents hidden in the bushes. The old jungle site has been turned into a nature reserve of sand dunes and swamps. Other more habitable areas nearby, of woodland and fields, have been fenced off to prevent people living there.

The camps are clustered around three main sites along the highway: the roundabout by the hospital, the roundabout by the stadium, and the turn-off close to the old jungle. The state has now set up official amenities at these three spots – water points, toilet cubicles, and a few showers. This came after a long struggle and a court case taken by individuals without papers, supported by volunteers, with lawyers from Paris who had worked on cases against the jungle demolition.

The facilities are provided by La Vie Active, the same NGO that ran official services at the old jungle and container camp. These official spots also act as distribution points where the associations (charities) come at a set time with vans to give out food, clothes, and so on.

One point we should maybe note here: while it’s no doubt unwitting, the associations running these van distributions help the authorities’ policy of keeping migrants segregated outside the town. In the past, the town hall hated that migrants came into the town for the food distribution, or to get clothes from the church “vestiaire,” or medical treatment from the main clinics. Having all these services delivered away in the woods certainly helps whitewash the migrants out of Calais.

CW: What do the police do?

CMS: Apart from guarding the fences, the police also focus on the three distribution points. They come almost every morning to those areas. Sometimes they just park up and stay there by the distribution points for a few hours, sitting in their vans or standing outside. This intimidates people and scares them from settling. Then, when they get the order, they attack the camps. They work with the prefecture authorities who send their “cleaners” – employees who pick up the tents and people’s belongings. Apart from stealing tents and personal affects, the police like to spray tear gas. This is pretty much like the old days in Calais before the big jungle was allowed in 2015.

Also, of course, they patrol the crossing points along the highway. When they catch people trying to cross they sometimes arrest them and bring them to the detention center in Coquelles. Sometimes they put people in the van but don’t head for Coquelles. Instead they drive some miles out along the highway and just dump people in the middle of nowhere.

But often they just spray tear gas and chase people away. Sometimes they beat people up, using batons and kicks. Also, there is a lot of verbal abuse and intimidation. People complain a lot about the verbal insults – you dirty n****r, you black dog, etc. People find this particularly demeaning and somehow shocking. It’s as if maybe you expect the police to use a bit of force to clear you away from the fences, but the insults show they’re not just “doing their job,” they’re really reveling in their violence.

CW: Do the police arrest people away from the fences too, like when they used to patrol around the town and just round anyone up who looks like a migrant?

CMS: This happens less than it did before 2015. People feel fairly safe during the day. In the night, it’s more common. The police will drive around in vans and pick up people they see walking from the jungles to the town, or walking back from the detention center at Coquelles. We still have that thing where people get arrested and taken to Coquelles, then released and are arrested again when they’re walking back from detention. But on the whole, those kind of random controls are not so much the police’s main focus now as they were in the past.

CW: What is the effect of all these attacks on people? Do they actually deter people from crossing?

CMS: No, as we said, people have traveled thousands of miles and gone through a great deal to get to Calais. They are not going to give up now.

But what we do see is the very real effects of all this constant harassment on people’s mental health. I think this has really gotten worse. There are ever more fences and walls, its ever harder to live, as well as to get to crossing places. And people are chased relentlessly, like vermin. Forced out of the town, forced to hide and disappear. And the verbal abuse and intimidation compound that.

As it gets harder to cross, people may stay a lot longer around Calais than before. You also see an increasing number of people who have already been on the road for years, maybe they have already been refused asylum in other European countries, so they come here, seeing the UK as their last hope. This can lead to big problems with alcohol and drugs, and makes people vulnerable to traffickers and others willing to profit from their distress.

CW: You said the authorities have largely succeeded in clearing people out of the town center. Before 2015, a lot of people used to live in the town in empty buildings – both the officially recognized squats that CMS helped to create, as well as informal occupations that were more vulnerable to police attacks. Is that no longer possible?

CMS: Well, certainly there are no “official” squats now in Calais at all. Any recent attempts to open them have been shut down straight away by the police, whatever the law might say. That’s not to say it’s impossible to do again. But there haven’t been people in Calais really concentrating on trying to do that.

As for unofficial squats, people may shelter in buildings and survive if they keep hidden or are in very small groups that don’t attract attention. The town hall and police deny the presence of any “illegals” in the town, so they may prefer not to move against small groups that stay largely unnoticed. But there are no big or visible squats like in the past. These would be shut down immediately.

CW: There was a massive surge of aid and support organizations, mainly from the UK, into Calais in 2015-16. Has this kept up, or have the charities left now that Calais is no longer in the headlines?

CMS: Many of them stayed. This is a big difference from before 2015 – the presence of still quite large numbers of humanitarians, professionals, and volunteers, particularly from abroad. However, they haven’t really adapted their infrastructure or approaches so much after the closure of the big jungle.

There are still two big distribution warehouses in Calais. One is run by Care for Calais, which distributes mainly clothes, tents, sleeping bags, hygiene items. They also now work beyond Calais, taking stuff as far as Paris. The other warehouse is run by the French association L’Auberge des Migrants and the British charity Help Refugees. In the same building there is also the Calais Refugee Community Kitchen (RCK), which cooks and distributes food.

Help Refugees was a big player in the jungle, after raising possibly millions from donations in the UK. This gave it a lot of power to set the agenda, as many other associations came to rely on it for funding. Now Help Refugees is quitting its direct presence in Calais, but will continue to act as a foundation funding other groups.

There is also Utopia, which managed the former camp in Dunkerques, then turned to litter picking in the jungle, and now distributes clothes, food, and other items.

One of the most interesting developments has been the new day center run by the Catholic charity Secours Catholique. This is a big building in the town, on Rue du Moscou towards the port. It’s open Monday to Friday until five p.m. and has lots of activities like language classes, clothes mending, and even a radio station. There are water points and toilets, meeting rooms, and a big space where people hang out, charge phones, use wi-fi, drink tea, and play board games.

CW: One thing that’s interesting about the day center is that it’s right on the corner of Rue de Cronstadt, the street where CMS rented a warehouse and opened it as a social center back in 2010. That was shut down within days by riot police using a dubious health and safety excuse. What do you think when you see Secours Catholique running a center there now?

CMS: Of course the Catholic church is a lot more respectable and powerful than we were. But it’s an interesting indication of how the political landscape has shifted in Calais. In 2010, it would have been unthinkable for the church to support a project like that, let alone organize it themselves. CMS tried twice to open legal centers, the “Zetkin centre” as well as Rue de Cronstadt, besides the numerous squats. Both received an immediate response from the state. It was clear that a social center open to migrants in the town was a serious challenge to the town authorities, and they wouldn’t tolerate it. It’s interesting to think about how this has changed – whether the authorities are not so scared of a place like that now, or the official charities are willing to push further.

As for the Secours Catholique center, it’s far from perfect, but it is a space of possibilities. And, interestingly, they do seem to be working in a way that is less patronizing, less of a giver/receiver relationship, than some other charity attempts in Calais. They allow people to use the space in their own ways. And, as opposed to other associations, most of the people volunteering there are long-term Calais residents, including refugees who have settled in the town. The space is also used by groups like Legal Shelter that collects testimonies of police violence or accompanies people on asylum claims.

CW: It seems like quite a few of the main public roles of CMS, like running social centers or tracking police violence, are being carried out by more official organizations now. What do you think about that? And what role does CMS have to play now?

CMS: Yes, it’s true. Again, it’s interesting to think about how the landscape has shifted, about what’s seen as radical and unacceptable by the authorities and the charities, and what’s considered normal or acceptable. For instance, CMS were the first in Calais to really talk about and document state violence, with the “This Border Kills” dossier in 2010. That was seen as a radical move, few of the associations would go anywhere near it. Also, we were the first to open a squat dedicated to housing women and children. Now everyone agrees with challenging police violence, and everyone agrees with providing accommodation for women – if not everyone else.

But still there’s a big difference between our approach and how the charities work. You can talk about people’s miserable conditions of life. But why are those problems there in the first place? Why are the police going around beating people up in Calais, why are people hiding in tents in the woods?

It’s because of the border. These problems will exist, in one form or another, so long as the border exists—that is, so long as people facing bombs and exploitation in Africa and Asia try to get to the rich world that’s sending the bombs, and so long as our politicians and police try to keep them out. But, maybe apart from a few slogans on a demo now and then, the charities don’t mention the border.

So some of the actions, like making accommodation or a social center, may be similar. But we also have to think about the wider repercussions, the meanings of these actions. First of all, do they bring people together – people with or without official papers, people from Calais and people from far away? Ideally on a basis of equality, not just giving and receiving, but sharing and making a struggle together. And do they challenge the silence of the border, help force into the open those questions the authorities are so keen to hide?

Since CMS started ten years ago in 2009, you could say we’ve been causing trouble by challenging the authorities’ attempt to whitewash the town and the border. They have a vision of a clean white town – ethnic French people and British tourists shopping happily in shiny corporate malls. Hence all the efforts to push migrants out of the town, keep them hidden in the bushes. Whereas in reality, most of Calais is a boarded up ghost town, with very many white Calaisiens also living in poverty. The right-wing, anti-migrant politics hasn’t done anything to address that, just provided a scapegoat.

At least some of us in CMS have had a different vision of what Calais could be. Imagine a town where people with and without papers, French or migrant, meet each other freely, share experiences and creativity. Making projects together that could help bring the town back to life. And helping each other fight our common enemies.

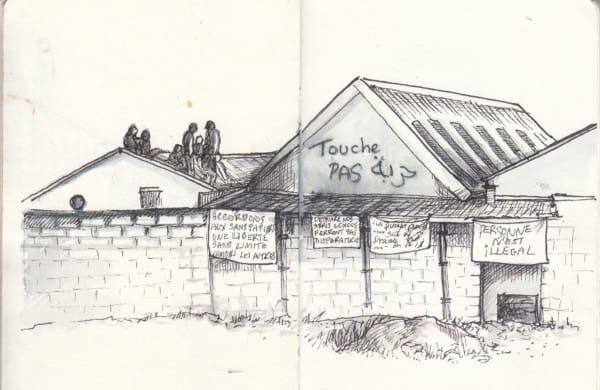

Drawings by Carrie Mackinnon, via Corporate Watch

i The word «jungle» is the term still widely used by migrants in Calais for camps in the woods outside the town. It was used long before 2015, including for the major Afghan jungle in 2009-10. It comes from the Farsi and Pashto word for forest, جنگل (jangal).