AntiNote: The following is a condensed compilation of three accounts from Greece. Two refugees share emotional testimony about the precarity and oppression they are experiencing on their journey (as well as their strategies for surviving it), and a friend they made on Samos island weighs in with a message of solidarity. Lift these voices.

Deep gratitude once again to the whole scattered crew that makes Samos Chronicles. They have been lifting voices virtually unheeded for a long time.

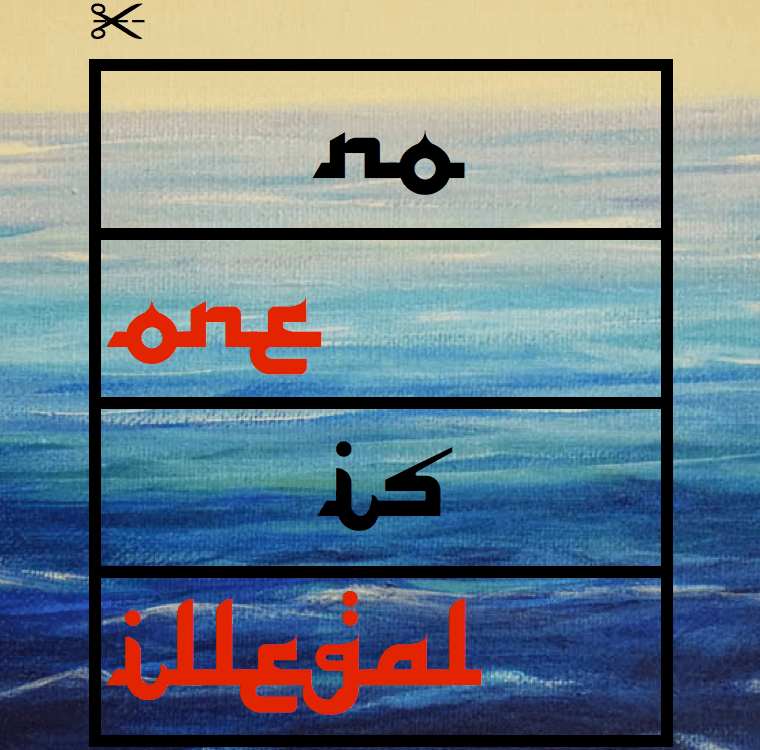

Refugee Lessons: Let Us Free Like the Birds!

by Saad Abdullah for Samos Chronicles

1 September 2019 (original post)

My life has been turned upside down and inside out. My brain has never had to work so hard to make sense of things, to survive and to live. For some of my hardest years, the system saw me and treated me as illegal. That is a big experience. I learned much. But above all I thought about being human and being free.

Syria

Now twenty-four years old, I was born in Aleppo in northern Syria. As one of the oldest human cities in the world it is rich with history. But I didn’t think of the city as a unique place. I thought that our cultures were everywhere in the world. As a young Syrian I couldn’t leave the country for many reasons, including money and international laws, which did not allow me to roam freely across the Earth. I had no direct knowledge of the world other than Syria.

After the winds of war tore up my country, I was forced to leave Syria without any options other than escaping into Turkey, illegally. For the first time in my life I came to understand the incredible importance that humans give to “papers” – passports, IDs, visas, and so on. If I had been a bird in Aleppo I would have been free to go where I wished, with no thought about papers or borders. For birds and all other living creatures on this Earth, borders have no meaning. We seem to be alone among living things in restricting this universal right.

Turkey

When I arrived in Turkey I discovered that there are people who speak a strange language (my first feeling), which is Turkish, and they do not know Arabic. I thought that I must learn their language so that I can communicate with them, but the Turkish language was not the only obstacle; the Turkish way of life I also found hard to accept.

In the short time I spent in Turkey, I experienced a society where men and women worked very hard for little money. Life for many seemed little better than prison.

One sunny morning I went to a public garden to sit under the sun. There were a lot of young and old people in the garden, and I approached one of them and said hi, but he refused to respond and then he said, “What do you want, do you know me?”

I returned to my house, where I heard the voices of the women in our neighborhood, which I did not understand, but they were very loud. It was strange for me that their women sit in the street and talk and prepare food and wear bright clothes whilst on their heads they put a colored cap that does not cover half of their hair, while their daughters wear short skirts and go from morning until evening to work. Their life looked very difficult and complex and I did not understand it well.

On Fridays I saw men streaming to the mosque to hear the Imam’s speech, which is filled with screaming, crying, warnings, and intimidations from god. And the people there were all crying and praying. But once they leave the mosque they go back to their hard work, and later, tired after long hours of work, they drink beer (which is not allowed in Islam) and eat dough mixed with chili (I don’t like chili!). There was a simplicity to this life, but it was so hard, and I felt that I was never accepted as a refugee from Syria. I felt that I had to become like them in order to live with them.

After some days I decided that I couldn’t make a new life in Turkey so I left for Greece—again “illegally.” There was no other choice for me. I am no longer afraid of illegal travel. I have been a homeless and guilty refugee—as some people in the world seem to see me, and as international laws want me—but in fact I am a bird traveling wherever he wants.

Greece

When I arrived in Greece (Samos island), I could not roam the streets or travel between the islands because I was forced to live in a cage, a camp for refugees.

The Samos camp was full of refugees of different colors, shapes, and languages. For the first time I met many different people who I hadn’t been able to meet before, such as Ethiopians and Afghanis, Pakistanis, Indians, Egyptian Arabs, Algerians, and many others. I did not know that all human beings were so alike and that we eat similar food with a slightly different taste and that Afghans and Pakistanis have a lot of cooking skills. Others were into sports and learning languages, and the prettiest of all of this was the chance I had to touch the body of one of the black refugees from Africa without fear, and I knew they were human beings like us. And it was in Greece where I had the opportunity to meet and know people from Europe and North America.

How beautiful it is to be a free bird.

Despite all these great and new experiences, there were many difficulties in getting close to people from so many different societies. There seemed many issues which held us back from accepting one another.

Even gays from Arab and Asian countries—and Greece as well—seemed closed to themselves and do not seem to like any person except gays. But I think that is a reaction because many people don’t accept them. How hard it is to be different and to be a friend to all people, they see you as different and you see them as different and both of you are afraid of the other.

The Greek government allowed me to fly to its capital after much time and trouble, to start another tale.

Athens is not similar to Aleppo or Izmir, and was so different from them, with people from many countries and cultures. But this did not change the nature of its people who love to dance and party, drinking beer and raki, which is the best alcoholic beverage they have. This may be nice for them, but I was very surprised that most of the workers I saw in Athens were immigrants and refugees from Asia and Africa.

It was not difficult to talk to the young Greek people because they speak English and I have enough to make conversation. Their pronunciation of the English language can seem strange as they speak a new language with a strange voice, but the bigger problem was with the old people who speak only the language of their country.

If I hadn’t met my English friends, life would have been harder for me in Greece. It was also great that my English friends are sociologists, which helped them and me better understand the Greek people and others. I began to realize that I too had been influenced by the place where I grew up, where the air I breathed was not so open and fresh.

In Greece, which is one of the gateways into Europe, you find a lot of refugees fleeing from their walled countries—and many of them are also seeking to escape from Greece. The reason is that they are looking for a country that does not have racism, fences, and prisons, and is full of safety and love and coexistence. And where you have a chance to make a new life. Greece is a beautiful country but it is so poor that like many refugees I couldn’t see how I could make my new life there.

It seemed to me that most of us still carry in our minds many feelings of distrust and lack of acceptance of those different from ourselves, just as we are looking for people different from us and to become like them. I experienced a lot of persecution from other refugees, which made me think that the freedom we are looking for is still infected by the poisonous air from the societies where we once called home. Even now I am still trying to understand all of this!

Netherlands

My illegal journey finished in Greece. I was so lucky when the Dutch government allowed to me to go to Holland by family re-unification. They recognized me as a free, legal bird. A few weeks after my acceptance, I took the travel documents and went to Athens airport to stand there just like anyone else, and could now say I am here! I am a legitimate bird so you have to let me get on the plane.

I arrived in the Netherlands, with my beautiful loyal dog Max, after I got financial help from my British friends to buy tickets for me and my dog and some money to buy food, clothes, and bags.

The journey was very beautiful, but the fear of another shock was in my mind all the time. I arrived in that beautiful green country, which is trying to escape from the water, which is threatening it from all sides. Should it win, then will I be safe with Dutch people or should I learn how to swim, to start my journey again but this time as a fish not a bird? That was the first question in my mind. Crazy!

In the airport in Amsterdam, my friend was waiting for me to take me to his house in Enschede where he is living. It was not a house, but just one room he shared with another three Syrian refugees.

These were not the easiest days for me in the Netherlands, because I was living with my friend and Max, my dog, in a small room. I couldn’t relax because these Syrian birds didn’t accept me and my dog with them in the same house, and because they saw me as a “fucking feminine” boy so they wanted to fuck me or for me to leave the house. They didn’t accept Max either, because they said it is not allowed in Islam to have a dog in your house. I tried to talk with one of them and explain to him that we are both human and that I am a good person and not what he thinks, and his answer was “Why you are talking with me? What do you want?”

My question is, is he right that I shouldn’t have talked to him and every person must make his life in a small shell? Or is he a psychiatric patient who needs treatment in order to learn to live with others?

Smiles

Before going to my friend’s house I had to spend a few days in a camp sorting out my papers. I arrived at the refugee camp after a journey of more than three and a half hours, but the beauty of the nature and the houses there made me forget everything. In my whole life I had not seen more beautiful buildings and more beautiful grounds for a refugee camp. Wherever you look, you find trees, flowers, and small houses with red roofs, white doors, and policemen wandering around camp on bicycles with big smiles on their faces.

I cannot forget those smiles that explained the meaning of life and assured me of my humanity, which I feel has been ‘imprisoned’ since I was a child growing up in Aleppo. And it was not only the smiles on the faces of the police, but wherever you go, you find people smiling at you and greeting you as if they knew you for years or as if you were one of their family.

Even the refugees living here were painting their faces with the same smile. Perhaps the secret is that when you see this smile everywhere and all the time, it will draw on your face without thinking. This experience made me very happy, because I never imagined that there are people smiling for all people even if they have different colors, religions, shapes, education levels, races, and passports.

The story does not end here, but the smiles still accompany me everywhere here in the city where I decided to live in the east of the Netherlands. Every morning and evening, I go out with my dog for a walk. I see people around me smile and greet each other, and they greet me too. That is really the key to life, and this is a beautiful society which seems to accept all cultures, and with smiles welcomes all people and all creatures.

Perhaps the Netherlands is not the only country with these wonderful qualities, but this is what I have discovered so far. Life is going on, and my wings are stronger and longer now that I’ve got legitimate wings. But I will never forget: legal or not, we will never stop trying to fly, free like the birds in the sky.

Saad Abdullah

August 2019

* * *

Nea Kavala Camp: Hell in Northern Greece

by Abshir for Samos Chronicles

2 September 2019 (original post)

I cried when I heard that the Greek government said it would send a thousand refugees from Moria camp on Lesvos to Nea Kavala on the mainland. They wanted to relieve the pressure on Moria, with all its new arrivals. I heard that the refugees to be moved were all seen as “vulnerable.”

I wanted to shout out: “Don’t go, please don’t go!”

I was a “vulnerable” refugee on Samos, and in March this year I was moved to the mainland with over three hundred refugees from Samos. I was sent to the Nea Kavala Camp. I lived there for four months.

It is hell.

It is cruel.

It is shit.

If I had known what was waiting in this desolate camp in northern Greece, I would not have moved. They would have had to carry me there by force. But I knew nothing of this camp. They told me nothing. They never asked me if I wanted to move.

When you are held on the islands, like Samos, you get the idea that the mainland is a better place to be. They say this a lot on Samos. The mainland has better resources and facilities than the island. This is what we hear.

As I quickly learned, this is not true at all. And yes, I want to shout this out. Please listen.

Nea Kavala camp is one of hell’s chosen spots in Greece. To think that this government sees it as a suitable place for vulnerable refugees shows to me how much it must hate us. Nobody should be expected to stay there.

Shock! All of us from Samos were shocked by what we found there. It was so unbelievable. In just a few days, many whom I had traveled with left the camp, disappearing into the night to try and find a better place to stay in Thessaloniki or Athens. They had nowhere to go. Most had little money. But they wouldn’t stay.

First, Nea Kavala camp is an old military airfield. It is in flat and boring countryside. There are no trees. It is isolated. It is at least a twenty minute walk to the nearest shop. The nearest village is a forty minute walk. What you see are lines of tents and cabins with no shade and no protection.

I was in my own room in Samos town. I shared a bathroom and a kitchen. It had a washing machine. It had electricity. It had wi-fi.

In Nea Kavala I was given a tent. I was on my own, at least, which was something okay. But no bed, no electricity, no reliable wi-fi, no personal security (my tent was robbed four times of food and clothes). Now I faced long queues for the toilet, for the shower, and days waiting to wash my clothes. Because I was given the tent and food, my monthly allowance was cut from 150 to 90 euros. The food from the army was disgusting. I couldn’t eat it or face the queues and stress in getting the food, so lived for most of the time on croissants, bananas, and milk from the supermarket.

Of course I had to stop my Greek classes on Samos. But in Nea Kavala there was nothing like that. None of the people responsible for the camp stayed at Nea Kavala. Even the camp manager, who I got to know, only came for a few hours a day. She told me she was frightened by the place. The only people there all the time were some soldiers involved with the meals, and some police. The police could not be bothered with us. I reported my thefts each time, only to be told to go away. They were always rude and aggressive.

Nea Kavala is in the north of Greece near the border with Macedonia. It has long and cold winters. In the first few weeks it was very cold at night and we had a lot of rain. On my second night there, an old woman in the next tent died, and I am sure the cold finished her life. We had just one blanket each. Over Easter, the sewage system broke and I found a river of sewage flowing past my tent. It took days to repair because of the holidays.

Then came the summer. We cooked in our tents. No shade. Nowhere to cool off. Torture.

This is where they are sending over a thousand vulnerable refugees. There will be many children and older people. Their tents are waiting!

I am sure that there are other mainland camps that are just as bad. I just know Nea Kavala. It is not a place for human beings. The refugees being moved there must be told. The world must be told. When you now hear that refugees are being moved from the islands to the mainland don’t assume that they are going to a better place. Listen to us! Don’t stand by in silence. Please.

Abshir, (Somalian, 26 years old)

Note from Samos Chronicles: They have arrived now. “We left Moria hoping for something better,” said Sazan, a 20-year-old Afghan, referring to the main camp on Lesvos. “And in the end, it’s worse.” (from France24: Migrants deplore conditions in new Greek camp)

* * *

Moving Stories

by Chris Jones et al. for Samos Chronicles

2 September 2019 (original post)

Many issues are highlighted in these two stories.

Firstly, the powerlessness of the refugees over where and how they live. Their needs and voices are simply ignored. Refugees are given little or no notice, whether it is moving house or moving off an island. Abshir and Saad had five days’ notice. As I write, the minster for migration is on Samos for a few days, and he has just announced that when he leaves at the end of the week he will be taking hundreds of refugees with him on a Greek navy boat. I wonder if the refugees affected have been told yet? The casual way in which the agencies act in moving refugees without any negotiation or discussion, with complete disregard to their needs and circumstances, reveals (once more) the fundamental lack of solidarity and respect for refugees.

Secondly, there is no sign that the authorities grasp or understand the critical importance of place (home, locality) for refugees as they wait for the asylum system to process their applications. In Saad’s case, he had been in Greece since October 2016 and in Athens for over two years waiting for his final interview in June. As with thousands of other refugees, his ability to survive these months, when his life was virtually stopped, came down to his friends. His apartment became part of a network of places where friends could meet and in many cases find a bed in an emergency. His home was crucial to his well-being. This has now been taken away from him.

For his part, Abshir has his asylum interview scheduled for January 2021. As far as he knows, he could be in Nea Kavala camp for two more years.

Thirdly, these stories challenge the widely held view that refugees are better off being moved to the mainland from the camps on the frontier islands. It would seem that many assume the conditions there must be better than on Samos.

Virtually no one questions the mantra of “decongesting” the frontier islands. It is a mantra shared across the political spectrum and voiced by virtually every refugee agency and NGO in Greece. Here on Samos, no questions are asked about where and what happens to the refugees who are moved. Of course no one asks the refugees what they think.

But there is no innocence in “decongestion.” The authorities and the NGOs know very well that what awaits many of the refugees on the mainland will mark no improvement in their lives and may very well be worse than what they have left behind on the islands. But they say nothing to those leaving, and do what they can to stop people from refusing to leave.

There is a madness to decongestion. In the week Abshir left with 350 refugees for Athens – heralded on Samos for relieving the pressure on the camp – a similar number of new refugees arrived. It is like watching a child trying to empty a bath while the water continues to pour in.

The camp in Vathi is an outrage. No argument. But then you are drinking tea with a 34-year-old refugee from Gaza who has beautifully painted and fitted out the recently opened Banana House, a new refugee space, in Vathi. Over tea, he shows off photos of his tent in the jungle around the camp. It is amazing. From the outside it looks as desperate as all the other tents and shelters clustered among the olive trees. But! Inside his homemade cabin under the trees, he has created a place of wonder and comfort. It has a floor, carpets, storage cupboards on the wall, a fireplace, and a small kitchen area. He lives there with his wife and daughter. The man is a genius. There are many others who are perhaps not as talented but who have created some comfort in such extreme conditions. They, and not the authorities, have done this. It is theirs. For many, their resilience as refugees rests on these kinds of activities and the spaces they create for living, meeting, and talking; passing time as best they can as they wait. All these factors make arbitrary removals highly disruptive and damaging.

Without a doubt, after being detained on Samos, being moved to the mainland carries more than the mere scent of new freedom. For some, detention on Samos has gone on for up to two years—and all have been on Samos for months at least. So it is with some hope that they leave the island for the mainland.

But the way these refugees’ movements – big and small – are managed makes them problematic and flawed. When it suits them, major NGOs (among others) will draw attention to the trauma of refugees, and in particular the psychological damage to refugees from being corralled in disgusting camps, as on Samos. But what of their compliance in cruelties such as moving people from their homes without notice or discussion? Silence. Where, in this one part of the refugee experience in Greece, does one get a clear sense that refugees are human beings with all our individual and paradoxical dimensions? Nowhere. Watching the refugees who are being moved off on the ferries is like watching sheep being herded. It is dehumanizing.

Sometimes small individual stories take us to much bigger issues, and in so doing reveal much—especially illustrating the impact of macro policy and ideology on lived daily experiences. Abshir’s and Saad’s stories are such examples. For as they share their experiences, we see just how pernicious and damaging is the European insistence of placing deterrence at the very center of its refugee practices, at least with respect to the kinds of refugees that come to islands like Samos (it does not apply to those with wealth and who are offered “golden visas” and the like). As we see every day on Samos, deterrence allows no space for humanity, dignity, or respect. Deterrence does not allow for compassion and care. It is the very opposite of solidarity. And for refugees, the consequences are distressing at best and lethal at worst.

Featured image: Nea Kavala by night. Source: Abshir. All images via Samos Chronicles