Transcribed from the 11 February 2020 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Mixing humans and nature in a way that pleases capitalist corporations is a complete contradiction. Capitalism depends on separations, putting boundaries between things, and privatizing different parts of nature for commodities.

Chuck Mertz: We are living in the anthropocene, a new geological age where humans are the most dominant force on Earth, even more powerful than nature itself. Or are we? How does knowing we are now the planet’s most dominant force affect the way we view the planet and ideas like conservation?

Here to help us understand conservation in what people are calling the anthropocene, sociologists Bram Büscher and Robert Fletcher are coauthors of The Conservation Revolution: Radical Ideas for Saving Nature During the Anthropocene.

Bram is professor and chair of sociology of development and change group at Wageningen University and holds visiting positions at the University of Johannesburg and Stellenbosch University. Robert is associate professor in the sociology of development and change group also at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. He is co-editor-in-chief of Geoforum and associate editor of Conservation and Society.

Robert, let’s start with you. You write, “A revolution in conservation is brewing. This is not necessarily an event that makes everything different—rather a growing urgency and pressure are building towards radical change.” Once I talked to a park ranger whose expertise is in forestry, and he explained that in his view, there are conservationists who want to keep nature in a certain state, conserving nature as it existed at a certain time. He then also defined environmentalists as those who wanted nature to take its course. I spoke to a biologist about those definitions, and while she found them interesting she wasn’t sure if that was framing it in a perfectly accurate way.

So Robert, how would you define conservationism, and how is conservationism different from environmentalism? Or are they the same thing?

Robert Fletcher: First off, there are lots of different approaches to conservation—it’s a conversation among different positions and different strategies, none of which really agree on essentially what they’re doing and what it really means. At the base of it all, there has been a history of trying to do exactly what this ranger suggested to you: to cordon off nature from human activity and preserve it in a state that seems to be pristine (even though it isn’t, necessarily).

Conservation, in that form and also in other forms that we discuss, is one aspect of environmentalism—but of course environmentalism can take very different forms that don’t necessarily have to do with conservation itself. I’d say conservation is a subset of environmentalism.

CM: So Bram, what is the pristine time that they look to? This sounds like nostalgia for a past, and often when that happens, that past is misremembered, fictionalized, becomes something even mythical. So what is the pristine past conservationists look to?

Bram Buscher: That’s a very good question. Many of the conservationists we’re talking about don’t really know that themselves, and they’re having the hardest time defining the baseline. And because this is impossible to decide on, because we literally can’t get back in time to look at what was before, we will be surprised to see how many people have always been influencing landscapes in one way or another. The easiest way to solve that problem is to have the idea of wilderness-without-people front and center as part of the imaginary of pristine nature.

In the literature, the question of baselines becomes really important. At some point you have to establish this baseline and work towards that to re-establish it in the future. In the Netherlands there is an interesting local park, where the idea of a baseline was very different from the standard ideas of baselines for European nature. The standard idea was it’s all forests—thick with forests. But an alternative baseline that was suggested was maybe it looked more like the Serengeti. Maybe it’s more open grasslands and things like that. Why don’t we try to recreate this kind of nature based on grasslands? You get a very different type of nature preserve as a consequence, of course.

We think that these ideas are very interesting. They tell us a lot about how we live with nature today, but they don’t necessarily say a lot about what we can do to ‘conserve’ nature. Because they are imaginaries. They don’t tell us how to live with nature and biodiversity currently, and how that fits into broader political and economic contexts.

CM: Robert, let me follow up on Bram’s response to that question. Where do we get that baseline from? Was there a period of romanticism about nature when suddenly we came up with this idea of a pristine time in nature? Where do we get that baseline from?

RF: The baseline is almost always right before people showed up in any given landscape. There are different ways to determine that: ecological methods like going down in the Earth and trying to figure out what actually existed at that point in time. But usually we have this idea that what existed before was the environment populated with the plants and animals that you see, only more of them and in different varieties, just with the difference that humans weren’t part of it. The main aim, then, is to get the humans out and to allow nature to take its course, usually, without the influence of people.

Usually now we get a baseline for what pristine nature used to look like from parts of protected areas where the former inhabitants have been cleared out. It appears to be pristine nature—these are the things we always tend to see in nature documentaries. It looks like the pristine nature that we imagine would have been found before humans showed up on the scene, but is in reality the result of very human processes and long periods of occupation and change. So it really muddies the idea of what a pristine baseline could even be.

CM: Bram, you and Robert write, “In the last decade, a number of radical alternate approaches to contemporary mainstream conservation have emerged. The two most prominent of these are New or Anthropocene Conservationism on the one hand, and Neoprotectionist or ‘Back to the Barriers’ movement on the other. Together these have caused quite a rift among conservationists.”

What is the difference between the two? I can’t help but think by accepting the idea that we are living in the anthropocene, we are giving agency to the same contributors to climate change in the first place. So what is the difference between the Anthropocene and the Neoprotectionist approaches?

Conservation has always been very central to the development of capitalism. It was a big part of the enclosure movements that forced people off the land in rural areas.

BB: It’s an important distinction, and there are several core issues that separate them. Two of these are the relations between people and nature on the one hand, and the way they approach capitalism and the broader political economy on the other. New conservationists have critiqued mainstream conservation basically by saying conservationists have been working against the poor, as Rob was just saying, dispossessing people from the lands that they’ve lived in for a long time by creating protected areas. But separating humans and nature as the main strategy to conserve nature is not really integrating biodiversity into the broader society and the economy. That is then also their solution. They’re very blunt about this. They are literally saying instead of scathing capitalism, we should really integrate conservation into capitalism’s culture and ways of doing things.

Neoprotectionists, or “Back to the Barrier” ecologists as we call them, are very critical of both these positions. They are quite opposed to them. Of course there are nuances within these broader groups, but what they would say is that we should put fairly clear boundaries between people and nature in all kinds of ways, but also clear boundaries on where humans can live, how many humans there should be more generally—most of them are very much also against the idea of further population growth, think we should limit human population growth, and so on.

Interestingly, a large part of the discussion is also about limiting growth and consumerism more generally. Some take a more political-economic approach to that, hinting at the power structures behind it that we really try to make explicit by connecting the history of conservation with the history of capitalism more broadly, but some leave it more vaguely at establishing limits to all kinds of things: limits to where humans can live (there could be thirty or fifty percent of the terrestrial part of the Earth reserved mainly for nonhuman nature) but also limits to growth, limits to consumerism, limits to population growth, and those kinds of things.

This is where they really don’t see eye to eye. They accuse each other of not being conservationists at all. When we look at those differences in much more detail, even though they seem very stark in the debate, the critique of Neoprotectionists on consumerism and growth is not actually very profound. They don’t go into deeper political power dynamics of contemporary and historical capitalism. We think that the idea of mixing humans and nature in a way that pleases capitalist corporations is a complete contradiction in terms. Capitalism depends on separations, putting boundaries between things, and privatizing different parts of nature for commodities. That doesn’t really make sense to us.

This is then where we come with our broader analysis and an alternative way forward.

CM: So Robert, then, mainstream conservationism seems to be based on the view that we are ‘stakeholders’ in nature, and we can save it with market economics. To what extent are stakeholder approaches, and capitalism (as it is embraced within mainstream conservationism), a threat to nature? The way conservationism has been approached in the past—has it played a role in nature’s destruction and in climate change?

RF: That’s a very good question. The way conservationists have framed the conservation, it’s been an alternative to capitalism, a thing that tries to separate off pieces of nature from the forces of capitalism. We argue that conservation has always been very central to the development of capitalism. It was a big part of the enclosure movements that forced people off the land in rural areas, forced them into the cities, where they became an urban proletariat. Conservation and capitalism have actually been closely entwined from the beginning, even though conservationists tend to go back and erase that link in the past.

More recently, what conservationists try to do is use capitalist forces as the basis for generating income and revenue to support conservation itself. In this case, we could argue that these mechanisms have not been good for nature, not good for the environment. But they haven’t been wholly destructive of it. They’ve mostly been problematic in terms of obscuring or disguising the things that capitalist extractive processes are doing, by making it seem that these can become sustainable, that they can be “offset,” that they can be rendered part of a more sustainable capitalism more generally.

That’s what I see as the real danger of these market-based mechanisms. They keep us in the solution that we can use capitalism to solve the problems created by capitalism itself, and don’t recognize that this is, as Bram said, a fundamental contradiction in terms. Capitalism is the fundamental threat that we really need to be facing head on.

CM: Bram, you and Robert write that “Mainstream conservation is fundamentally capitalist and steeped in nature/people dichotomies, especially through its foundational emphasis on protected areas and continued infatuation with images of wilderness and pristine natures. Phrased differently, mainstream conservation does not fundamentally challenge the hegemonic global capitalist order, and is firmly embedded in myriad dualisms wherein humans and their society or culture are seen as epistomologically and ontologically distinct from nature.”

Can there actually be conservation of nature without fundamentally challenging what you call the hegemonic global capitalist order? Is the capitalism of conservationism being challenged today? And is that the biggest debate within conservation? That is, is capitalism either compatible with or in competition with nature? Is that what the debate boils down to, or is that oversimplifying the debate, Bram?

BB: Yes and no. You’re right, it does ultimately boil down to that, but it’s often phrased in ways that don’t really make that explicit. The very term capitalism seems to be very scary for many people (even though that is changing as well). Simply looking around us, with the Australian fires and everything we see—if we just look, not even closely, it’s pretty clear that the economic model we have these days is not sustainable.

But does that mean that it’s also talked about in relation to conservation in those ways? Last year there was a report that came out by IPBES, an intergovernmental panel on biodiversity and ecosystem services, and it was really a landmark report. Not only did it conclude that over a million species are threatened with extinction if we continue business as usual—over a million species; just imagine that—but it also said that we need transformational change. This is a bit of a euphemistic approach to refer to questioning growth and those kinds of things. Literally prince Charles of England two weeks ago also said that we need a different political-economic model. Yes, slowly but surely, more and more people within conservation are actually questioning the foundations of capitalism—just without necessarily always referring to capitalism in and of itself.

There is something rather weird and contradictory about millions and millions of people flying across the world to spend some money to protect biodiversity in faraway places.

People are afraid to say this, to make this explicit, and then to confront this head-on, as Rob said. We want to open that up. Just because we’re talking about capitalism doesn’t mean that we need to say that everybody involved in everything that happens these days is evil or bad. For us it’s a very simple position: namely that it’s just obvious. We need to move beyond capitalism if we want to be sustainable, because there is indeed a foundational antagonism between longer-term sustainability and forms of human development. We want to take a very down-to-Earth, normal position where we start thinking about how we actually start doing that. It’s about confronting power, on the one hand, but also thinking through what other ways we can imagine in order to build new institutions, new ways of working together, new ways of making sure people have decent food, ways of living with perhaps dangerous wildlife, and so on.

Having criticized this for about fifteen years, I still believe it’s incredibly necessary, especially because capitalism is so hegemonic. But also, at some point we came to the conclusion that we just have to get over this. More people will have to come to that position one way or another. It’s so obvious. Let’s just take that step and start thinking what could be.

CM: Robert, does capitalism, then, impose that nature/culture dichotomy upon us? Can capitalism exist without that nature/culture dichotomy, that separating, that cutting off of humanity from nature? Or is that what capitalism depends upon for its bottom line, for its success?

RF: Historically, capitalism has been one of the main forces that ends up creating that sense of separation. I want to preface that by saying there isn’t any thing called nature. Nature is itself a construction. There are different species, and different ecosystems, and dividing that into different realms, one called Nature and one called Culture, is one of the things that capitalism as an economic process has always done, in different ways.

Originally, there was a separation between the countryside and the city, where city life was sustained by cannibalizing the resources of the country. Then it went global, and there came distinctions between developed and “underdeveloped” countries. We had similar types of exploitative relationships in which some places were rural and other places were urban, different configurations of nature and culture. Now we’re seeing new mechanisms where pieces of nature are cordoned off as the basis for conservation finance, the idea that we leave resources in the ground rather than extracting them, and use that non-extraction as a basis of trying to generate revenue: things like paying for “environmental services,” reduced emissions through avoiding deforestation and land degradation, carbon markets, and those kinds of things.

There are still distinctions between nature areas and cultural areas. But those distinctions and where they fall change over time. Whether that’s absolutely necessary to capitalism, and whether capitalism could find a way to go beyond that and actually develop a new form that doesn’t require these kinds of divisions—I can’t speak to that. Capitalism has been shown to be endlessly creative and capable of morphing in ways that no one would have predicted it would in the past, and it’s quite possible it’ll continue to do that into the future.

CM: Bram, you and Robert write that “The alternative if convivial conservation is the most optimistic, equitable, and—importantly—realistic model for a conservation for the future. While the term convivial conservation may be new, many of its premises are not. Numerous Indigenous, progressive, youth, emancipatory, and other movements, individuals, and organizations have long been working on and engaged in alternative conservation practices and ideas that include elements of what we propose here.”

First, Bram, how would you define convivial conservation? And can we simply take what has worked in the past and just apply it to the present? Is it as simple as that?

BB: No, certainly not. Convivial conservation is not a blueprint. Conservation (and also the broader development scene) is quite full of these magic silver-bullet type solutions that don’t work. They don’t take into account histories, contexts, positionalities of different people, and so on.

Convivial conservation, for us, is both a politics and a governance program but also a set of practical mechanisms, practical things that conservation could start doing immediately in order to create and stimulate change in the right direction. We don’t posit convivial conservation as something that on its own could ever lead us into a sustainable world. To move into post-capitalism is a broader issue than conservation in and of itself could ever hope to achieve.

But conservation is of course very central to it because of the central relationship between humans and the rest of nature, between humans and the biodiversity base that we all depend on. That’s where we see an important role for the conservation community: in broader post-capitalist struggles. We think that the community should take this on.

That aside, what is convivial conservation? Conviviality as an idea literally means living with. For us that already signals that we must live with the rest of nature, not separate ourselves from it. That’s the first, most immediate connotation. Second, convivial conservation comes from older ideas around conviviality that have certain connotations in the English language, obviously, but its literal meaning has to do with being skilled in conversation. To actually do justice to all the contradictions and the conversations that we were just talking about, conviviality moves through them to find a way forward.

As a set of governance mechanisms and more practical things, we could talk about it in quite a bit of detail. But we separate long term and short term measures in order to re-focus on reintegrating humans and nature and moving beyond global capitalism. One is that we advocate a move from protected areas to promoted areas. We need to get away from the idea of protection. Rob came up with a slogan for convivial conservation: “From Protection to Connection,” meaning to re-embed protected areas in their social, environmental, political surroundings in order not to separate ourselves discursively from the rest of nature, not to feel that we need to protect nature from humans—or ourselves from ourselves, basically—but that we can learn to live with different types of nature in more mixed landscapes. Some are wilder than others. Some are more human-dominated. There can be all kinds of different gradations between those. But that certainly is one step to deal with protected areas towards the future.

The danger of the anthropocene frame is that it makes it seem like there’s been a linear progression whereby humans multiply and start degrading the ecosystem. It’s much more complicated than that.

Another one has to do with tourism. Tourism is often hailed as the savior of nature, and brings in cash for conservation. But obviously there is something rather weird and contradictory about millions and millions of people flying across the world to spend some money to protect biodiversity in faraway places, as many people actually do these days. It’s one of the world’s largest industries, of course. We advocate a move from this kind of superficial, tick-the-box tourism—seen-that-done-that, five days Kruger Park, six days Costa Rica, ten days wherever—to longer-term, engaged visitation so that you can do more justice to an area. You don’t have to see everything, but look at the social surroundings of these areas so that you can appreciate all kinds of nature in its social contexts.

That’s a little bit of a harder sell. It’s not a nice marketing slogan. But to a degree it’s what people have been doing for a long time. Would it mean going back in time? No. But certainly, it’s learning from ways different types of people in the world still live with all kinds of nature in ways that does justice to them and the biodiversity around them.

CM: Robert, I really love your phrase “From Protection to Connection.” One of the words that we always hear associated with environmentalism is stewardship. I think that term might be problematic. You two write, “The social scientists who accept the anthropocene see positive potential in how this new reality forces humans to acknowledge the extent to which their actions influence the planet, and to therefore take their obligation to responsibly steward it more seriously.”

Is stewardship control? Is the idea of being stewards of nature nothing but a repackaging of human control over nature? Is one a slippery slope to the other?

RF: Yeah. I don’t think it necessarily needs to be thought of in that way, but it often is, and it is problematic. It’s a very fine line. We need to recognize that humans do have tremendous influence over the planet, even to the point that we’re really starting to make it unlivable for ourselves and other species due to climate change and other issues. But on the other hand we don’t really have control in some larger sense. There are a lot of processes that are still very much beyond our control.

Somehow finding the fine line within that means recognizing both our potential to make things better for ourselves and for other species through changing the ways we live and interact with other species, while at the same time having some humility in that process and recognizing that our control is less than we tend to think of it. We need to be cognizant of the fact that there are all these other processes that happen without us—and that our actions lead to unpredictable outcomes—and to be able to accept those limitations.

It’s both trying to make sure that the things we do are done in a manner that allows us to coexist and live sustainably with other species, while at the same time limiting that and trying to scale it back to the point that we don’t impose ourselves over these other places and species. It’s that fine line that we’re trying to get to through the idea of convivial conservation. But it’s a very difficult tightrope walk.

CM: Bram, you write, “The question of whether we should label our current era the anthropocene is important. A better descriptor for this new phase in human history is the capitalocene, as argued by Andreas Malm, Jason Moore, and others.” Andreas has been on our show a couple times. His writing is spectacular. Why is capitalocene a better term to use than anthropocene? Does capital have more control over nature than humans do? Is that why we have climate change? Because capital has conquered the Earth and now controls it more than humanity?

BB: The idea of the anthropos as some generic humanity leaves completely out of the picture how differentiated this humanity is, and that certain people have always done more to stimulate these processes, and have also structural benefited from these extractive and dominating processes than others. So there is no generic anthropos, some generic humanity, as Andreas Malm and others show very clearly.

Humanity in and of itself didn’t lead to the situation that we find ourselves in where we face climate change, rapid Earth system changes, biodiversity loss, huge inequalities, and so on. The basis of that is indeed capital. Capital, for me, is very simply defined as putting forth money or resources to get more of those: to get more money, to get more resources. It’s an endless cycle of accumulation. That in and of itself is the motor that drives this broader system of capitalism, and hence why we should call this era the capitalocene rather than some generic anthropocene.

At the same time we may not want to get too much into the semantics of that game, but more the logic of the analysis behind it—that will lead to other ways of looking at this going forward. For us, that’s part of the politics of convivial conservation. We talk about details and pragmatic stuff, but also the whole analysis leading up to it, and the logic behind it. That will hopefully help people find solutions in very context-specific situations, rather than some overarching blueprint that they can just apply.

CM: Robert, what would you to say to someone who argues this is the anthropocene because human-caused capitalism is leading to climate change—that a human-caused and -controlled factor, capitalism, is causing climate change and it is the dominant feature, so this is human-caused climate change; this is the anthropocene because we created capitalism?

RF: You’re right in that sense, but it’s important to think about it a bit more deeply, get a bit more nuanced, and recognize all the different things Bram is talking about in terms of different groups of people and their embeddedness within these political and economic systems. Those are the things we should be focusing on. The danger of the anthropocene frame is that it makes it seem like there’s been a linear progression whereby humans multiply and start degrading the ecosystem. It’s much more complicated than that. If we just look at that simplified narrative, then it doesn’t allow us to get to the roots of the issue and be able to build the kind of sustainable future that we need.

CM: Bram, was the right correct all along? Is climate change and environmentalism nothing more than a socialist plot to overthrow not only the government of the United States but global capitalism?

BB: That’s complete nonsense of course. Obviously it’s a rhetorical trick—it has nothing to do with left or right whatsoever. We all live on this planet, we all need to deal with it. But perhaps one side of the equation is a little more realistic than the other, has their eyes a little more open, or perhaps are less embedded in these power relations than the other, and is able to look at this a little bit more clear-sighted, and on that basis think about ways out that benefit all of us, including people on the right. They too would benefit from a healthy environment. I guarantee you that.

CM: Bram, I really appreciate both you and Robert being on the show with us this week.

BB & RF: Thanks!

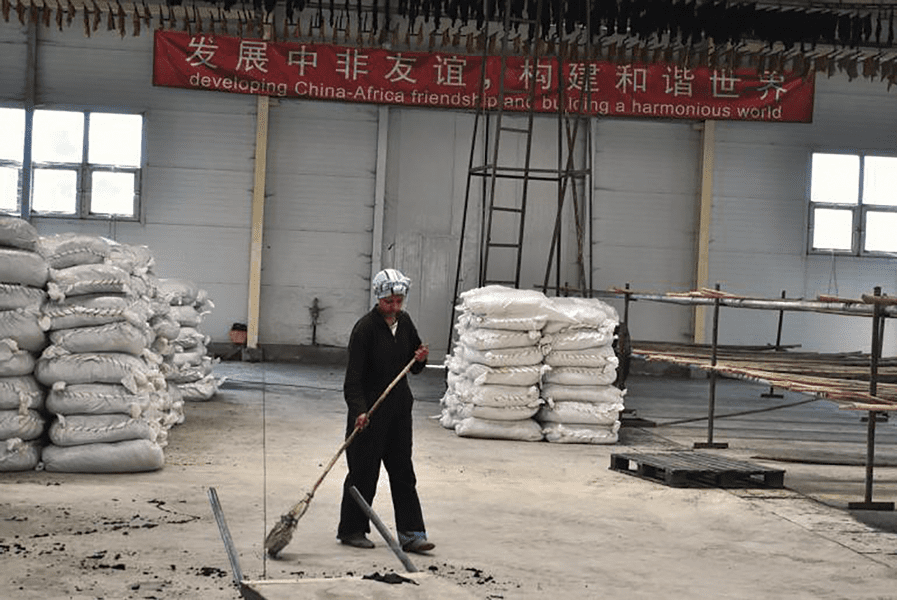

Featured image: generic wetland photo stolen from a capitalist conservation site, with zero remorse.