Transcribed from the 11 May 2020 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

One of the key things that “managing” migration has meant in recent decades is keeping migrants and refugees outside of the visible framework while at the same time working through a process of selection.

Chuck Mertz: The US continues to push down the road the issues facing refugees and migrants fleeing their homelands in search of safety and survival, hoping that time will somehow solve their situation. But it never does, and conditions keep just getting worse for those detained. Here to tell us about Europe’s externalization of their migrant and refugee issues, and why that keeps making things worse, social activist Pavlos Roufos wrote the Brooklyn Rail article “A Disaster Foretold.”

Pavlos was on the show in 2018; he had then just written a book called A Happy Future is a Thing of the Past: The Greek Crisis and Other Disasters. Pavlos is a social activist and writes in Berlin, and he’s been active in Greece’s social movements since the 1990s. He writes on a semi-regular basis about the economic crisis for the Brooklyn Rail as well as Berlin’s Jungle World. Pavlos has worked as a film editor and is currently a PhD candidate on German economic policy and ordoliberalism at the University of Kassel.

Welcome back to This is Hell!, Pavlos.

Pavlos Roufos: Hi Chuck, very nice to be back, thanks for inviting me.

CM: You write, “When the Greek government’s council of national security declared that it would be closing down its borders with Turkey on March 1, 2020, the language used fell nothing short of one announcing a military operation. The militarized escalation came two days after president Erdoğan announced that Turkey will open its borders to Europe to ease the burden of a new wave of people fleeing war-torn Syria.

“A parallel observation is warranted. There is nothing sudden about what happened in March 2020. What came into the open during those days was instead an entirely expected and consistently predicted consequence of a situation that has been building up for at least five years. The pretense that this was unexpected served only as a pathetic attempt to deny this simple reality and as a diversion from the inevitable conclusion that the migration policies of the last five years made such events unavoidable.”

Delaying the inevitable is not sustainable, and the longer you avoid the inevitable, the inevitable always seems to get worse. Why, in your opinion, does capitalism delay the inevitable instead of addressing it? Why would capitalism threaten its own long term sustainability by making problems worse by delaying?

PR: That’s a structural question about capitalism. The simple answer would be that capitalism is a system of social relations that has very deep contradictions that cannot be resolved within its own framework. The way capitalism progresses historically is to try to mediate or mitigate those contradictory relations and conflicts for its own profit. There are moments in time when that becomes unsustainable, and that’s when we see the explosion of social antagonism, conflict, and revolutions. But to the extent that none of these have been successful, the story continues.

CM: Why does capitalism do so poorly in a crisis?

PR: It really depends how we define “poorly,” because what we know for sure is there is a recurring crisis happening in the history of capitalism. It is pretty obvious that this system, this mode of production, cannot avoid crisis coming back. But I’m not sure that we can say it has been doing poorly. From the perspective of capital, those crises so far have been overcome or at least put in the background, and without reaching the point that they actually threaten the continuation of capital.

If we look, for example, at the economic crisis of 2007-8 and the Eurozone crisis of 2010: we are ten years out now from these times. Capitalism was seriously threatened, to a certain extent—the continuation of this economic system was under threat. The people on the top were actually panicking. But ten years later, even despite those contradictions and problems, and despite the social movements that emerged, what we have is a continuation of more or less the same recipe.

So I don’t know if one can really say that capitalism is doing “poorly” in crisis. It’s probably more accurate to say that capitalism lives through crisis.

CM: You write, “In tandem with the logic of the wider organization of global capital, the situation of migrants and refugees corresponds to what Mike Davis recently described as an ‘ongoing triage’ whereby significant parts of the world’s population are effectively made invisible and written off.”

Why does so much of the world want immigrants to be invisible? For migrants and refugees not to be seen? What do they represent that we do not want to recognize or realize about the world in which we live?

PR: There are different ways of answering that question. There are historical ways to look at it. But I would focus on a couple different aspects. First of all, the question of migration is as old as human history. It is not something new, it is not something that has changed, it is something that has been descriptive of the passage of humans through this planet. The whole world has been built around migration. Our day today is not different.

Why do they appear as invisible especially today? We could say they always have. But there are two reasons that make the situation even worse today. One is what Mike Davis described as ‘triage,’ that the development of the economy cannot accommodate large parts of the population that seem to have been abandoned. We can see that already in developed capitalist countries in terms of how they treat their own populations and the poor in those places. The US is a perfect example of that.

But in the hierarchy of oppression, if such a thing can be used, it is even worse for those who cross borders and reach different places from the ones that they were born in. One of the key differences that they have from the rest of us is that they are not immediately acknowledged as having the same rights, the same opportunities, the same humanity. This is what I understand by Mike Davis’s succinct description, this triage: people are written off entirely and they’re not even considered; they are a second-class category of people.

If we can frame migration policy in the last thirty or forty years within a specific context, one of the key things that “managing” migration has meant in those decades is keeping migrants and refugees outside of the visible framework while at the same time working through a process of selection. I’m talking mostly about Europe now: certain migrants, through a process of selection, might be allowed to enter the national territories of different member states of the European Union, but this will be done in a very specific, “effective” and organized, bureaucratic way. The rest will be left out and not allowed inside.

“Security” and the uncertainty that term brings, and the fear that is created by propagating this migration as a “foreign invasion” (as they did in Greece in early March 2020) creates a completely different set of understandings and approaches that influence the way the population understands and relates to the issue.

In order for that to happen, what the European Union has done for quite some time now is externalize the issue. They make countries bordering around Europe responsible for keeping migrants at bay, not allowing them to cross into European territory, and in exchange they get some cash or funds or whatever—different agreements have been drawn up. This, unfortunately, has quite a long history, it didn’t start in 2015 either. It goes all the way back to deals that Italy had with Gaddafi in Libya before the regime was overthrown. This is the main understanding: you keep migrants and refugees outside; you do not allow them to enter European territory or to have access to the rights and responsibilities that are meant to be given refugees and migrants according to international law. You keep them invisible, you keep them outside, and you perform a process of selection according to different considerations (like economic considerations). And you select a few to be allowed to go in. That is the framework within which migration policy has operated in the European Union.

That framework was threatened in 2015 when there was a massive movement of people. A majority were from Syria, but not only from Syria. They were from other countries as well: Afghanistan, Iraq, all the way to Pakistan and countries in northern Africa. But there was a collectivized movement of people who were all crossing the borders together. Operationalizing the migration policy of closing down borders, making selections, and leaving out the rest in the the outskirts of Europe did not really work in 2015.

CM: You write, “By hiding the cruel treatment of migrants and refugees behind inaccessible internment camps in countries with ambiguous relations to international protection agreements, the EU hoped to maintain that it remains internally a union that respects legal procedures and its own regulations, while at the same restricting irregular movements.”

Is the EU acting above the law? Outside the law? Does passing laws and invoking regulations and then not enforcing those rules work in leading the public to believe that their society is more humane than it actually is? Does this kind of ploy work in convincing citizens of the EU that the EU is far more humane than it is in reality?

PR: To a certain extent, the EU does uphold the international regulations and agreements that it has signed. It does do that—internally. Once you are inside Europe, a certain “understanding” of the legal process has to be kept. This is one of the reasons that in Greece there were specific developments concerning the migrants in camps and their relocation to the mainland and so on.

But—and this is a key point—countries with which the EU has made deals in order to manage migration, such as Turkey or Libya, are not upholding international regulations in the same way. The Geneva Convention that deals with questions of migrants and refugees has not been fully signed, for example, by Turkey. They signed it with a territorial clause that allows them to differentiate between migrants and refugees. Turkey, up to this moment, is required by law to give full rights and be responsible for migrants and refugees only to the extent that they come from Europe. It does not have the obligation, according to international law, to treat migrants and refugees from other countries with the same rights.

This is a very blind spot for the EU-Turkey deal, which was the legal framework of the outcome of 2015. Many commentators and writers have pointed out that Turkey does not fulfill the legal obligations for being designated a so-called “safe third country” to which migrants and refugees could be sent instead of Europe—but at the same time Europe can pretend that the regulations, international treaties, conventions, and all the necessary agreements within the EU are being kept.

What happens in Turkey is a different situation, and it is not up to the EU to decide it—at least this is what they pretend. In most cases they would say they are pressuring politically and diplomatically for Turkey to expand its recognition of official international law and agreements. At the same time, the reality for the last five years has been desperate. There are quite a large number of migrants in Turkey. Maybe many listeners in the US do not know, but Turkey has approximately 3 to 3.5 million refugees from Syria and surrounding areas, a quite significant number of people, and they have been there since the beginning of the Syrian war in many cases.

In contrast, Europe, the big event that changed the whole discourse and situation in Europe concerned 1 million people. The contrast is quite significant. It’s difficult to avoid. And one should pay attention to the fact that 1 million people crossing into Europe created a huge mess, increased nationalism, xenophobia, and racist attacks against migrants—whereas in places like Turkey and other countries, the actual migrant population is much larger and under different circumstances.

It is worth noting in general when talking about migration that the biggest number of migrants and refugees are located in developing countries and not in the developed countries. This is also something that needs to be taken into account, and a lot of people don’t notice that. The whole propaganda around migration is centered around the idea that migration and border crossings represent some kind of security threat or destabilizing factor for developed countries, whereas the reality is that the overwhelming majority of migrants and refugees are in this moment located in developing countries.

CM: What is the lens through which migrant and refugee policy is created within the EU? Is it through a lens of security? Is it through a lens of economic relations? Is it through a lens of humanitarianism? I’m trying to understand the position from which the EU writes their migrant and refugee policy.

PR: All of the above, I would have to say. They are all part of the considerations they make, but of course they don’t all carry the same weight. If I tried to separate those issues, I would say the number one priority would be economic concerns. The European Union and the European monetary union are primarily economic units and nothing else, so the economic concern is right at the center of considerations.

But of course the economic concern itself is not easy; it is a complicated issue because there are different national economies with different needs and different considerations on that issue. For example there is Germany, which has an observed problem with demand—Germans do not spend a lot. There is a problem with the aging of the population that creates issues with insurance and social security. And then there are countries that have very low labor supply—so migration from that perspective would be a very positive thing to bring people who would fill out those spots (usually low paid and precarious, but that is a different issue). From the economic perspective there are reasons why migration is seen positively, and this is one of the key reasons why neoliberals (at least some of them) are also in favor of opening borders and allowing migration—but purely to the extent that this could be economically accommodated and absorbed.

When there are families who come from places that have been bombed, of course there are going to be people in a vulnerable state. There are people injured, people with health issues; there are unaccompanied minors, people with severe psychological trauma. All of this is absolutely logical. For that reason, it is very normal to designate them as vulnerable groups. But SYRIZA tried gradually, in different ways, to minimize the legal categories that would pass as vulnerable.

The question of security plays a role in understanding the ways policy has been created. But it is not the central one. There are numerous reports, one after the other—an endless list of reports—that show the absolutely overwhelming majority of migrants do not pose any security threat whatsoever. This is absolutely clear to everyone who takes the time to look around at what’s happening. At the same time it is quite useful to present the question of migration as one of security. “Security” and the uncertainty that term brings, and the fear that is created by propagating this as a “foreign invasion” (as they did in Greece in early March 2020) creates a completely different set of understandings and approaches that influence the way the population understands and relates to the issue. So the security question plays a part, but mostly as a propaganda issue. It is not something that actually has any particular force.

The last bit, the humanitarian aspect—this is also true: the humanitarian aspect comes out of the legal situation. The legal process is framed around issues of humanitarian help and giving aid to people in need. At the same time, there is a liberal understanding of migration that is very much interested in distancing itself from far-right nationalist expressions and their understanding of migration as something entirely hostile. There is a liberal understanding which has a more humanitarian approach towards the question of migration.

But at the end of the day, the migration policy of the European Union is a process of externalizing and then managing a selective few who manage to come through. What they try to do is balance between the far-right, racist, outright rejection of migration and the more liberal humanitarian acceptance of migration, up to a certain point. There’s always this sense that you can’t just open the borders and just allow everyone to come in and give them equal rights, because that would completely abolish the whole idea of how migrants can be exploited.

In any case, this approach to managing migration does try to balance between these two. It does not accept the outright racist hostile position, but it also does not fully endorse the humanitarian liberal view. It balances this out, and gives a little bit towards the liberal side by saying we’re going to have a selection, we’re going to have a managed migration policy—and then it also gives a little bit to the right wing by making sure that the borders are closed, that they are militarized, and that agreements they make ensure that third countries take the “burden” of dealing with those thousands, millions of people who are trying to escape war, poverty, and absolute destitution.

CM: These policies were put into place under SYRIZA, not the current government under New Democracy. But a lot of these policies put in place by SYRIZA—they took out PTSD as a sign of vulnerability that affects Syrian refugees. They would accept them into the country at one point based on PTSD as a sign of vulnerability, but they took that away. SYRIZA was deploying a lot of migrant and refugee policies (just like the Obama administration was) that were then adopted by the rightwing government that came in following them.

Did SYRIZA have to oblige those rightwing tropes when it came to migrant and refugee policy in order to stay in power? Because it didn’t keep them in power. I’m trying to figure out why hate is something that is such an integral part of the migrant and refugee policy not only in the EU but within Greece, when that is a policy that is only forwarded by a very vocal minority of the population.

PR: As we have discussed in the past, I don’t have a lot of positive things to say about SYRIZA, but at the same time we need to be fair and objective. I don’t think one can actually say that SYRIZA is responsible for this hate. What SYRIZA did, in the same way as it did in the economic sphere, is fully comply to EU policy. They did that, and as soon as they accepted that this is the situation, they went in over their heads to overcompensate having initially presented themselves as hostile to such policies.

During SYRIZA’s time, of course, a lot of negative things happened on the migration front. Of course there was a problematic situation. This was framed (and this is not an excuse) in terms of how to make EU policy function. How do we implement it in the best possible way? The main framework of the migration management program of the EU was the EU-Turkey deal. SYRIZA, as the government of the country in which the EU-Turkey deal was meant to be implemented, was trying to find the best way to do that.

One of the things they came across as an obstacle to implementing the EU-Turkey deal was the fact that migrants or refugees who are recognized as belonging to vulnerable groups are not going to be eligible to be immediately sent back to Turkey. This is a legal situation, this is something recognized by the United Nations and all the international migration authorities, so they are obliged to follow that process. What they ran across, however, was that a lot of people were being classified as vulnerable.

In a certain way, it makes absolute sense. When there are families who come from places that have been bombed, of course there are going to be people in a vulnerable state. There are people injured, there are people with health issues, there are unaccompanied minors, there are people with severe psychological trauma. All of this is absolutely logical. For that reason, it is very normal to designate them as vulnerable groups. But SYRIZA tried gradually, in different ways, to minimize the actual categories that would pass as vulnerable, in order to stop them from being exempt from being sent back to Turkey.

That was one of the things that SYRIZA definitely did. There are other examples that do not show SYRIZA in a good light. At the same time, we also have to acknowledge that New Democracy has been much worse on the question of migration. The New Democracy government was elected in the summer of 2019 with a number of promises, mostly around the idea that they’re going to get rid of SYRIZA and its incredible failures or whatever. These promises were on the one hand based on economic improvement: they said they were going to lower taxes, increase wages, everything that every political party says in a pre-election period to appease the public.

But the economic reality in Greece is that none of these measures could actually be implemented. Even though Greece is now formally outside the memorandum of understanding agreements and the bailout mechanisms, it is still supervised and monitored by the EU and the European monetary union, and they have very strict limits on how they organize their budget, where they spend, what they can cut in taxes, and so on. There was also an “automatic stabilizer” put in place during SYRIZA’s government—this is kind of like the neoliberal wet dream. It means whenever spending (public spending or state spending) crosses a certain threshold, then immediately a cut will be made from another part of the budget without any process requiring parliamentary certification or discussion, or even publicity. It’s not even publicized.

These mechanisms are already in place in Greece, so New Democracy could not deliver much at that level, despite its promises. But what it could deliver is the second side of New Democracy’s paradigm as a rightwing party: law and order. When New Democracy was elected, knowing they could not do many things, they focused on law and order, presenting things as if we were at the brink of absolute collapse and social conflict, which is of course nonsense. One of the issues they used for the law and order campaign was the ridiculous idea of “cleaning up” Exarchia. Exarchia is a small neighborhood in the center of Athens that has a history of anarchist and radical left agitation. This is a different topic, but it is indicative that New Democracy, as a national government, could base a policy of law and order on one small neighborhood in Athens. That in itself is kind of indicative.

The biggest threat that migrants and refugees are facing is not from local vigilantes, fascists who once in a while get together and mobilize against them. The biggest threat comes from the actual policies that are being implemented at a state level.

Having said that, the second way New Democracy promised to re-establish law and order (as they said) was the question of migration. There they did significantly different things from what SYRIZA had done. One of the first laws passed by this government—not just on the question of migration but in general—was cutting off access for migrants and refugees to healthcare. That was one of the first things that they did as an elected government.

Further along the line they promised to initiate a process of what they called “decongesting” the islands. Because of the EU-Turkey deal, one of the key geographical locations where migrants end up when they cross the border to Greece are islands where there are various makeshift camps. They are supposed to be organized, but they are not. These camps have horrible conditions, and of course the numbers in the camps have been increasing, for a variety of reasons that I can explain if I’m not speaking too much:

In the last few years, the only way for migrants who arrive in Greece to reach the mainland was through a program run by the United Nations that rented out housing and apartments and could organize the transport of people from the camps to the mainland. There’s a limit to the number of people who can be transferred, because there is a limit to the number of houses that the United Nations can offer. There are other reasons why the transfers were being blockaded, but I won’t tire you with details. Let’s just say that the migrant population on the islands was increasing beyond the capacity of the camps and beyond the capacity of the organizations that were working there, and there were many, many people being concentrated, and that created a backlash from local inhabitants.

New Democracy came saying they would solve this problem quick and easy. Their suggestion was to create new camps on the same islands, but closed ones. That was the main idea that they had. And because they had the support of local politicians and the local population, which had just voted for New Democracy members in the islands, they thought this would be an easy plan to implement. But in reality that’s not what happened. As soon as they tried to start building these closed camps in the islands, the local population reacted in a very confrontational way. There were massive demonstrations, and riots against the police that were sent from Athens to oversee the building of these camps. The population was so unified that the government was forced to withdraw police forces from the islands and stop the plan altogether.

CM: It seems like New Democracy kind of set the stage for the kind of violence that happened. Golden Dawn went to the islands, fighting for some sort of fascist autonomy they believe the islands could have. There were roaming vigilante mobs that were beating up migrants, some were even being killed. To what extent can we blame the rhetoric of New Democracy for setting the stage that led to the far rightwing violence on the islands against migrants and refugees?

PR: It’s a bit of a complicated issue. The situation in the islands has changed over the last few years. Although initially there was a lot of support—it was widely reported—and a sense of solidarity given to migrants and refugees in the Greek islands, that situation started to change after a while. And one of the key reasons the attitude of local populations changed was the realization that the presence of migrants and refugees was not a temporary one.

The support and solidarity that was happening was completely understandable, completely honorable. But it was based on the idea that these populations were in a transit phase, they were passing through. People saw what was in front of them—at the houses and the beaches where they went, they saw women and children and all people arriving in very dire situations, so they did help at first. Once the realization set in that the policies of both the EU and the Greek government were centered around the idea that the population would be permanently placed in those makeshift camps, the attitude in the islands started to change.

Of course it didn’t change for everyone; there was a huge presence of NGOs and all their workers and volunteers—all these people needed a place to stay, needed a car to move around; they would buy in the local markets. The same goes for migrants and refugees. Moria camp, which is located in Lesvos, now has approximately nineteen to twenty thousand people; these people get some money every month from the United Nations and the International Migration Organization, (90 euros per person or 250 per family, something along those lines), and all of that money is spent locally. So to a certain extent, the presence of migrants and refugees, plus the aid organizations and the NGOs, did actually revitalize a certain part of the local economy. A lot of people remained if not necessarily sympathetic, maybe indifferent.

Of course there were people within communities in the islands who did not see it the same way. They had no way of accessing those funds, so they started complaining. Now I want to make clear something that a lot of people are not always ready to accept. Some of the complaints that the local population had were justified. I use one example in the article: a local farmer whose land and animals are next to the camp has continuously complained about their olive trees being chopped down and their animals being killed and eaten by migrants in the camps. Of course if one were a farmer and everything they had was being lost, it is absolutely natural to have grievances and to complain about it.

But this is one of the key problems in how the question of migration is complicated: to try and think why this situation is happening and who is to blame for the harm. If we look at it from the perspective of the migrants, they are literally left with no other choice. As I said, those camps that they have survived in (some of them have been there for three, four, even five years) are completely makeshift. The population is so large that they have spilled outside the few buildings that were built, and people live in tents—in the cold winter with snow, people live in tents that have absolutely no heating whatsoever. Of course if you’re in a situation like that, any one of us would have done the exact same thing; we would have cut down a tree nearby and used it for a fire to warm ourselves. If eating means you have to stand in line for three hours to get a bowl of soup or some lentils and rice to feed your family, then of course if you see a goat or a pig, you might be tempted to go for that.

So the reason why migrants were forced by circumstances to resort to certain actions was absolutely understandable as well. The key question in my mind is how a situation like that brings two different groups into conflict, and the people responsible for the situation are not the ones being blamed.

CM: Are migrants and refugees on the Greek islands better or worse off with the global pandemic?

PR: The lockdown made it more difficult for local fascists and racists to mobilize and demonstrate, and to repeat many of the things they had done in early March—making roadblocks and attacking migrants or even NGO members who were just passing through. They could not do that, for sure.

But the biggest threat that migrants and refugees are facing is not from local vigilantes, fascists who once in a while get together and mobilize against them. The biggest threat comes from the actual policies that are being implemented at a state level. This is what keeps migrants in a position of vulnerability, keeps them under threat, and allows for fascists and racists to utilize the situation to make hate speeches and mobilize people.

The greatest fear of everyone I spoke to, when I was in Lesvos just before the lockdown was initiated, was what would happen if there were COVID-19 cases reported in the camps. This population is already in triage. They are already written off. Right now if you look at the United States or the United Kingdom, you see governments that are not interested in dealing with the problem for their own population—you can imagine what that would mean for migrants that are already written off. So the biggest fear was how to avoid a misanthropic backlash in case there were some kind of COVID-19 outbreak in the island.

This has not happened yet. I think we’re extremely lucky, we have to say that. It’s still unclear what will happen. There were some cases reported in camps on the mainland, but the biggest camp on Lesvos still hasn’t recorded any cases. But what the government has done is, in a way, even worse: they forbade migrants from leaving the camp. One of the key things that migrants could still enjoy under the circumstances in which they live was to go outside to the main cities, to do some extra shopping, to feed themselves, to walk around on the seafront, to have a coffee, to have a drink, to feel like normal human beings. That was one of the key things that they could do, despite the fact that they had to live in Moria camp.

Now this has been taken away. With the excuse of the COVID-19 threat, migrants are not allowed to leave the camps, and they are stopped and fined if they are caught outside the camp. If they go to the supermarket for some rice and vegetables, they get caught and they get fined. The fine in Greece if you get caught outside, and you haven’t got permission to be outside, is 150 euros. As I said before, migrants receive 90 euros per month. So you can imagine what that means.

This is how the government has been treating the issue. At the same time, they have tried to move many people from Moria to the mainland. They have started moving 1,500 mostly unaccompanied minors towards the mainland. But this has come across various problems as well. Just last week they tried to move a group of fifty women and children—and I cannot emphasize this enough, women and children—to a hotel in the north part of Greece, and local racists and fascists mobilized and burned down the hotel, so they could not take those women and children to that hotel. This is the situation, this is how they reacted. So I haven’t got a lot of positive things to say I’m afraid. This is the situation we’re facing, and this is the situation we have to be constantly fighting.

CM: Pavlos, thank you so much for being back on our show.

PR: Thanks a lot for having me back.

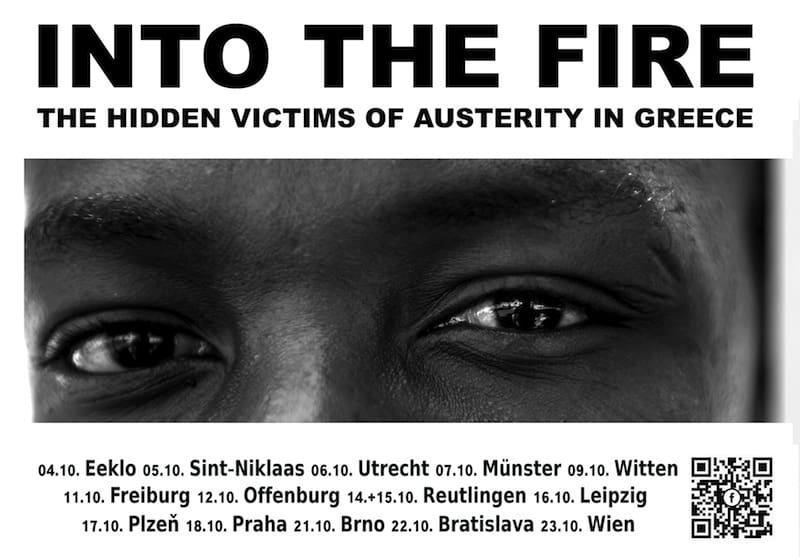

Featured image: Samos island, 2016. Although we are getting less diligent about republishing their articles, we strongly recommend the website Samos Chronicles for thorough and intimate updates on how the situation for refugees on that island has changed and worsened over the years. —AZ