Transcribed from the 2 June 2020 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Massive inequality, financialization of the economy, xenophobia, ultra-nationalism: these are all part of the logic of what I call neoliberal fascism. It’s misery conjoined with terror.

Chuck Mertz: When we want a clear reading of the impact that neoliberalism is having on our planet, we always turn to our next guest. Whether it’s the racial violence that killed George Floyd or the violence to our environment that led to the global pandemic, you can count on it all going back to the cruel system of neoliberalism. Returning to This is Hell! to explain: cultural critic, writer, university professor, journalist, and a member of the board of directors for Truthout!, Henry A. Giroux.

Henry, how are you?

Henry Giroux: Good, Chuck.

CM: In an article at Counterpunch, “Racial domestic terrorism and the legacy of state violence,” you write that the “sheer brutality of George Floyd’s death at the hands of a viciously violent cop symbolizes the unadulterated racism of a culture that looks the other way in the face of police violence against Black people, but also a society in which a form of racialized domestic terrorism has become normalized.”

You see this as terrorism. President Trump sees antifa as terrorists, not white supremacist groups who have a long record of hate crimes and violence in the United States according to the Southern Poverty Law Center. What does it reveal to you about the Trump administration, or US governance more generally, when the actions of police are not seen as terrorism but antifascists are seen as terrorists?

HG: Trump basically wants to militarize every possible space that he can in order to concentrate power, ruthlessly, not only in his own hands but in the hands of his racist, white supremacist, neofascist followers. Trump only knows the language of violence; he only knows the language of self-absorption, greed, and self interest. And he has a propensity to label anything—whether it’s oppositional language, oppositional journalists, or people suffering in the face of state violence—as terrorists, when in fact he’s the real terrorist.

His policies, whether they’re on the border dealing with undocumented immigrants and putting children in cages, or whether he’s telling the police to become more thug-like in dealing with people that they arrest (which of course is generally poor Black and Brown people), or whether he is enacting policies that destroy the environment—these are all acts of violence. What we have to ask ourselves is what the thread is that connects all of these. We’re not just talking about racism. We’re talking about massive inequality, financialization of the economy, xenophobia, ultra-nationalism. These are all part of the logic of what I call neoliberal fascism. It’s misery conjoined with terror, connected with what I call racial sorting.

CM: During the Obama administration, we did hear a lot of Republicans—especially those on the far right—complaining about the potential for totalitarianism, authoritarianism, and even the potential for martial law under the Barack Obama administration. And now we hear Donald Trump calling for, as you were saying, a militarized response not only to the coronavirus but also to the protests around the killing of George Floyd.

What explains to you why the far right would be so afraid of martial law under one leadership and then call for martial law under another leadership?

HG: These are all diversions. Anything the far right media says is the product both of their own political and economic interests, which align with Trump’s, and the fact that they’re sycophants. This is pure propaganda. There’s no journalism involved here. Let’s recognize what we’re dealing with: cultural apparatuses in the hands of the state that will say anything to defend their Leader.

I do take them seriously in terms of the influence they have in persuading people to believe in acting according to interests that are not theirs, and helping to consolidate the rule and power of elites. But to look for contradictions in what they say is to believe that at some level there’s a logic there. It isn’t about logic, it’s about power. These groups are nothing more than legitimating tools, disimagination machines. They sow divisiveness. They claim the pandemic was a joke designed to defeat Trump. When they talk about terror, they look at people who are fighting for their lives in order to survive. Everything is Orwellian. This is the Ministry of Falsehoods.

Certainly we need to expose these lies, but what we really need to recognize is who they are. They’re adjuncts to the consolidation of neoliberal fascist power. They can’t be trusted. They should be condemned. We need to fight for alternative media like This is Hell! that expose them and point out options that are more viable, and that are willing to understand the conditions that give rise to them. I’m more concerned about where they come from, how they’re funded, and whose interests they serve than I am in looking at the contradictions that come out of their idiotic mouths every day.

CM: In your writing on the coronavius, you write, “The other plague, among many, is the rise of cultural apparatuses such as Fox News and Breitbart media in which truth is treated with scorn, science is viewed as a hindrance, and critical thought is maligned as fake news. This is a plague of willful ignorance and state-sanctioned civic illiteracy.”

Willful ignorance? Why would anyone will themselves into ignorance? And can that happen on both the right and the left?

HG: It certainly can happen on both the right and the left. There are no political guarantees just because one operates from a particular ideological position. But we do want to recognize that people on the left basically operate from a position where they’re talking about social justice, equality, and making the world a better place. Some of them slide into political purity; some of them might distort the truth in some ways. On the other hand, on the right we’re not talking about people who have a vision of a better society—we’re talking about people who want to justify inequality, racism, racial violence and state violence, and the destruction of the environment. We’re talking about a death machine.

These are very different groups. Let’s begin with where they start from in order to understand that to say that the left lies and the right lies is a false equivalence. Let’s look at who has the power in this country. Think about the president’s comment about antifa. Is he really serious? Does he really believe that hundreds of thousands of people mobilizing in the streets of over forty cities in the United States are organized by antifa? These are such distortions of the truth that we really have to start asking ourselves what is being defended here. What is the root of this problem?

People cannot be agents if they don’t have a sense of history. They cannot be agents if they don’t understand the connections between what’s going on now and what’s happened in the past.

Of course the truth is being maligned. But the truth is always maligned for a particular purpose. You ask me why they would engage in willful ignorance. There are two kinds of ignorance: there’s the ignorance of just not knowing; and then there’s willful ignorance, which is the refusal to know, so you can reproduce your own particular interests, in this case the interests of oppressive power.

CM: One thing that’s really been bugging me about the coverage of the protests against the police violence killed George Floyd is that some who are supporting the cops will just say, “Hey, look, it’s just a few bad apples.” But when it comes to the “looters,” who might also just be a “few bad apples,” they appear to completely undermine the entire movement against police violence. The focus in the media and much of the public discussion is now on the looting, without deeper conversations and analysis on the racial violence imposed by the police.

HG: There are three issues here. One: if we’re going to talk about looting, let’s put it in a context that gives the term some substance. There are corporations, banks, and hedge funds and there are policies that loot from the American public and push whatever funds we have upward into the hands of relatively few people. That’s real looting. The financial crisis of 2008 was looting. We basically cheated people out of their homes: the banks gave them false mortgages. It goes on and on. We have tax breaks: 1.5 trillion dollars that go to the rich. We have a pandemic bill that serves billionaires and millionaires and does almost nothing for small business owners. That’s looting.

Secondly, “looting” is code. It’s code for a form of racism. When we talk about “looters” in the media, what we’re talking about generally is poor people stealing televisions from Target. That’s what’s going on here. There is a refusal to really think through what the term means.

Thirdly, the tactic is a diversion. To talk about looting and not talk about the conditions that produce it is to miss the point.

Fourthly, it seems to me—there’s yet another argument. There are many people involved in protests who were nonviolent and who said, “This is a diversion, we don’t support this, and we have to think through how we’re going to handle this while at the same time not condemning everybody who is involved in this sort of thing; we need to talk about it not just as a moral issue but as a strategic issue.” This is not beneficial, it seems to me, because it offers too many opportunities for a “law and order” president to emerge beating his chest and do a photo-op talking about how he likes protesters and loves Black people. These terms, when they get seized upon so quickly, especially by the mainstream press, are really supporting the kind of “law and order” they think they’re reacting against.

And one more thing has to be said: if we’re going to talk about “looting” as the destruction of property and not as the destruction if human life, we’re missing the point. If we want to talk about looting, think about the pharmaceutical companies, and think about how many people died because they purposely flooded the market with opioids, knowing that those drugs would kill people, and still did it, and raked in millions and millions of dollars. That’s looting. Were they put in jail? Were they described as criminals? No, not really.

CM: We were talking to Ariella Aisha Azoulay about her book Potential Histories: Unlearning Imperialism, and she was talking about how for instance in Palestine in 1947, Arabs and Jews were working together trying to find a peaceful solution, and that was overrun by imperialism. She said we have to remember those moments in time.

You write, “The people running into stores taking TVs are labeled ‘looters,’ when in fact as James Baldwin once said, captive populations don’t loot; hedge fund managers, bankers, pharmaceutical executives, big corporations and the rest of the ultra-rich are the real looters.”

I heard this James Baldwin quote attributed by a TV reporter to “young people today.” How dependent is the history of racial violence on the erasing of voices and movements against police violence that have risen up in the past, just like we see the erasing of the stories against imperialism that happened for instance back in 1947 Palestine?

HG: We’re not just talking about the erasure of impressive events that we should learn from in terms of understanding origins—we’re talking about the erasure and reconfiguration of historical memory in general. We live in a culture of immediacy; we live in a culture for which history is the enemy. We live in a culture in which historical memory is a term that belongs in some academic textbook and is not really part of the pedagogical practices that are necessary for people to become critically engaged citizens.

We’re talking here not simply about the crisis of history, we’re talking about the crisis of agency. People cannot be agents if they don’t have a sense of history. They cannot be agents if they don’t understand the connections between what’s going on now and what’s happened in the past. If you can’t connect the violence that’s going in the streets right now to 1968, if you can’t connect that to Jim Crow, if you can’t connect that to the rise of capital punishment in the United States, to the origins of slavery, to the genocide waged against Native Americans, you don’t get it. You don’t have an understanding. All you can hear is a president stand in front of a church making a phony speech about how we need law and order without any sense of how that term has been used as a weapon to literally kill people.

CM: You write, “Under the Trump regime, people of color are ‘thugs’ relegated to zones of social abandonment, lacking human rights, and unknowable as lives worthy of value.”

Lives being unknowable as worthy of value—is that simply a mechanism of neoliberalism, capitalism, imperialism, to have a labor force viewed as lacking value so others can benefit from their poorly rewarded work? Is that just the way that capitalism works?

HG: Go back and listen to the speeches of Malcolm X if you really want an answer to that question. One of the things that capitalism does is say that whatever strengths working class people have, whatever strengths Black people have, or Brown people have—whatever strengths the oppressed have are really not strengths, they’re deficits, and they should be ashamed. Basically, their lives are worthless. Basically, if they’re not good consumers they have no identity. Their histories don’t matter—the schools attempt to eliminate those histories. Arizona attempted to wipe from the textbooks the history of Mexican Americans’ families for their children.

The notion that the economy is more important than human life is really an argument for neoliberal fascism.

When you undermine the possibility for people to speak—to be voiceless is to be powerless. When you undermine and eliminate the narratives that give people a sense of their histories, that’s a form of depoliticization. It’s not just an attack on their self-esteem. It’s a way of refiguring history to suggest that the only people worthy of history are white people. The only people worthy of history are the rich. The only people worthy of history are the Donald Trumps. The only heroes we have today are the heads of tech companies. The CEOs. The crisis of historical memory is a crisis of agency, and it’s also a crisis of politics and democracy.

Do we need to learn those histories? Absolutely. Do we need, in some fundamental way, to be able to define ourselves so as to be able to think through who we are, and what our strengths are? There’s a term for that. As a working class kid I was defined by my deficits. You’re too emotional, you’re too kinetic, you’re too passionate—that kind of nonsense. I called it flipping the script: at some point I recognized that the things I was told to emulate in middle class and ruling class values were really despicable. Once I was able to flip that script, I understood that I came from a neighborhood where there was an enormous sense of solidarity among working class kids: that we hung together, that we had a sense of ethical responsibility, and there were all kinds of things that gave us a sense of community.

I think the key question here is how do we flip the script against dominant historical narratives?

CM: You write, “No one talks about the roots of these problems, and I do not simply mean their origins in slavery, a culture of lynching, and a deeply ingrained institutional racism, however crucial these events are. I am talking about the roots of a fascist politics in which money counts more than people, and some people count more than others.”

We heard people on the right being very concerned that the “cure” for the coronavirus might be worse than the disease: that the shutting down of the economy might be worse than the actual pandemic. They wanted to put profits before people instead of people before profits. Does putting the economy before the people—is that the definition of fascism?

HG: Max Horkheimer, a member of the Frankfurt School—when he was studying fascism, he had a great line: if you don’t want to talk about capitalism, you can’t talk about fascism. I think he’s absolutely right. We’ve seen the evolution of capitalism over the last forty years, particularly since the election of Ronald Reagan: it’s become more severe, extreme, savage, and cruel. What that basically means is it can no longer defend itself. It can no longer say it’s about social mobility, it’ll trickle down, we’re gonna raise people up from the bottom to the top—those things are just lies and they’re gone.

So now it’s turned to something else. They say the real problems, of course, are Black people. The real problems are people mobilizing in the streets. I don’t use the word riots. I say rebellions. People are rebelling in the streets. But they don’t use that term. The real problem is we’ve defunded education. The real problem is that people are suffering because they’re in debt and are afraid to access healthcare because they won’t be able to pay back the fees. People are dying because they don’t have enough food. People are dying because the economy has been financialized and there are no productive jobs anymore. People are dying because one in four people in America don’t have jobs right now. People are dying because 45% of those jobs won’t come back.

When you close down the future in the name of an economic system—and then, in the face of the misery it produces, say that the economy is worth some people dying—what you see is neoliberal fascism tying itself to the logic of genocide. Think about what was said in the pandemic about older people. “They can go, we don’t need them. Their lives are expendable. What really matters is keeping the economy alive.” That is a false choice. It’s not to say the economy doesn’t matter. It says that if we had a democratic socialist government that took half the funds they put in the military and provided people with what they need to survive and more while at the same time investing in health, investing in schools, investing in public goods, and doing everything you can to develop a vaccine…there is no dichotomy. The economy will come back. People will work. We’ll have national healthcare. We’d be able to address the problems that we have.

The notion that the economy is more important than human life is really an argument for neoliberal fascism. It’s a false argument. The other side of this is that it’s now become so brutalizing and so cruel, and so obvious and so visible, that it makes no apologies: some people should die so that the GDP can go up and the stock market can revive itself. Can you imagine?

CM: At the beginning of the pandemic response here in the US, the media and the government kept saying “We are all in this together,” in a repeated call for unity in this time of crisis. Under the virus, has that contradiction been revealed as unsustainable?

HG: It’s such false language. I saw a big billboard on the highway that said, “Pick up the trash, we’re all in this together.” Actually no, I’m afraid we’re not all in this together. Some people have power and contribute in an inordinate way to destroying the environment. My putting my trash in the green bin is not the same as corporations dumping millions of pollutants into the waterways, crippling kids, putting lead in the water in Flint and other cities, having schools where there are cockroaches running around and kids are being exposed to that, cutting back on food stamps so that people get sick and don’t have access to healthcare. I’m sorry. Three families in the United States control as much wealth as fifty percent of the bottom of the population—don’t say that we’re all in this together. We’re not all in this together.

Some of us are victims. Some of us are in this because we have no choice. Some of us don’t have the capabilities or the possibilities to address these problems, because we’re struggling to survive. The “unity” in that language is a false unity, as bad as the neoliberal argument that the only responsibility one has is to oneself, and the only way to address any problem is to blame oneself. It’s just a horrendously cruel and false argument.

CM: You write, “Neoliberal capitalism is the underlying pandemic feeding the current global shortage of hospitals, medical supplies, beds, and robust social welfare provisions—and increasingly, an indifference to human life.”

Here in Chicago, right in my neighborhood, there is a closed-down hospital that they started tearing down at the beginning of the coronavirus. Why don’t we ask why there’s a shortage of hospitals? You’d think that would be the conversation on the very first day. When they say we have a shortage of beds, you’d think we’d ask why we have a shortage of beds. We have a shortage of hospitals. Why do we have a shortage of hospitals? There was a political choice made to close down health facilities that were needed. Why is that question not being investigated in any way?

A whole range of questions coming out of this fissure are enormously important. What kind of society do we now want to envision?

HG: Because it’s too dangerous. It’s a question that exposes the very heart of a savage kind of capitalism which believes the market should control and govern all of social life, and therefore the social contract is the enemy, democracy is the enemy; public goods should not be supported; people who get any public benefit are moochers or greedy and stupid and they really don’t deserve that; we all have to pick ourselves up by the bootstraps; and if we want good healthcare we have to fight for it alone and prove that we’re worthy of it.

This is such a savage argument. This hatred of the social contract and hatred of equality translates into a massive endorsement of inequality. This hatred of compassion translates into a culture of enormous cruelty. This refusal to deal with the language that supports community and democracy translates into a language of divisiveness. Othering people because of their color—their class, race, sexual orientation—translates into the language of hate. And the language of hate translates into the language of violence.

CM: You write, “The many people who are dying and will die as a result of reckless policies towards coronavirus will be those traditionally viewed as disposable under the reign of neoliberalism. These include the elderly, the destitute, poor people of color, undocumented immigrants, and people with disabilities, not to mention the frontline medical workers who lack the equipment they need as they treat the elderly, the sick, and the dangerously ill.”

We’re all calling these people essential workers, whether they are grocery store workers or EMTs—for now. How can essential workers be disposable under neoliberalism? Does that show yet another fissure in neoliberalism?

HG: Absolutely. Just like the rebellions that have taken place in the streets all over the country right now, what the pandemic has made clear is that, I’m sorry, these populations are essential to how the country runs. All of the sudden the heroes are not bankers and the hedge fund managers. Nobody’s talking about Bill Gates as a hero right now. Give me a break. Jamie Dimond? See you later. The real heroes are the people who go out every day and put their lives on the line, the people who make the electricity work, the people who nurture the buildings, the people who provide the food, the people who do the jobs that make this country and societies all over the world function.

We’re discovering that. To me, that’s a sign of hope. Let’s talk about our priorities. What do we want to invest in? Do we want to invest in the upper one-tenth of one percent and shift all our wealth, money, interest, policies, and power to those people? Or do we want to ask ourselves the question: if we need healthcare, what do we do? If we need food, what should we do? If we need security for our children, what should we do? How do we hold back a government that endorses the police brutalizing Black and Brown populations? What should we do?

A whole range of questions coming out of this fissure are enormously important. What kind of society do we now want to envision in light of all these different pandemics we’re seeing?

CM: There had already been an epidemic of loneliness and depression sweeping the United States and the UK. What impact do you think neoliberalism’s language (as you call it: the language of isolation, deprivation, human suffering, and death) and its outcomes have on the ability of the US or UK public to emotionally and psychologically deal with quarantine? What impact does neoliberalism have?

HG: It makes it very difficult. Loneliness and social atomization—if I can put it this way, echoing Hannah Arendt—is a form of terrorism. It’s a form of terrorism when you separate people, break down communities, force people to simply think about surviving and nothing else—it’s a form of terrorism when you say the language of compassion is a disease and that the very notion of community or solidarity most be broken up and destroyed in the interest of pushing a particular ideology.

It’s really horrendous. People suffer for that. We’re social beings: we need to function in a way that allows us to work together, to be cooperative. We need a society of shared responsibilities, not a society based on shared fears. And that’s what we have: a society based on divisiveness, self interest, shared fears. It doesn’t work. It produces anxiety, precarity, fear, and loneliness. But it also produces something else: it produces a hatred for other people.

It’s a terrible, dangerous ideology that fosters a norm of collective fascism.

CM: Back in November-December 2008, we had a guest on talking about how we need to push the Barack Obama administration to make certain that it lives up to the ideals of the antiwar activists who helped him get into office. Immediately upon his getting into office Democrats everywhere said you can’t push him too far to the left or he’ll be a one term president.

How can we make certain that Democratic candidates, if they do get into office, do the things we want them to do instead of doing as Barack Obama did, which was a race to the center?

HG: You go in the streets. You’ve got to put a stop to all of this. That’s not a call for violence. It’s a call for new strategies that unite different groups in ways that shut the country down. We’ve got to shut down the power that dominates this country. You want to shut it down? Go for their pocketbooks. Occupy. Mass civil disobedience. Do what Martin Luther King did. Be selective. Shut down different things in this country at different times. Use those opportunities to educate people.

We’ve got to paralyze the system. The system has got to be stopped, and it’s not going to be stopped through elections that are a joke. It’s not going to happen that way. We need massive education, we need a unified mass movement, and we need strategies that work, that can make the machinery come to a halt—if temporarily at times—to make it clear that we cannot go on like this anymore.

CM: What is our future? If, once we are allowed to go back outside, we do go “back to normal?”

HG: The future is not inventing a future that mimics the present. The future is fighting collectively. The future is taking advantage of the energies of young people and bringing them together. The future is about getting rid of the factions that we see on the left. The future is to talk about a society that is just, equitable, and serious about democratic participation, economic equality, and social justice.

We need a new language, Chuck. We need a new language, and we need educational systems that produce it: we need radical imagination machines. We need an alternative media. And we need a mass movement that sees the question of education and the question of collective struggle as inseparable.

CM: Our guests on last Monday’s show argued it is inevitable that neoliberalism will fail under the virus. Can neoliberalism fail as long as the rich are getting more and more rich off of it?

HG: There’s no guarantee that anything will fail unless people become aware, through a process of critical understanding and critical action, of what it means to come together and invent a future that doesn’t reproduce the present. That’s an enormous political question, because it operates on the assumption that we need a new language, new agents, a new vision, and new possibilities.

CM: Henry, I love talking to you. Thank you so much for being back on our show again.

HG: It’s my pleasure, Chuck, thank you.

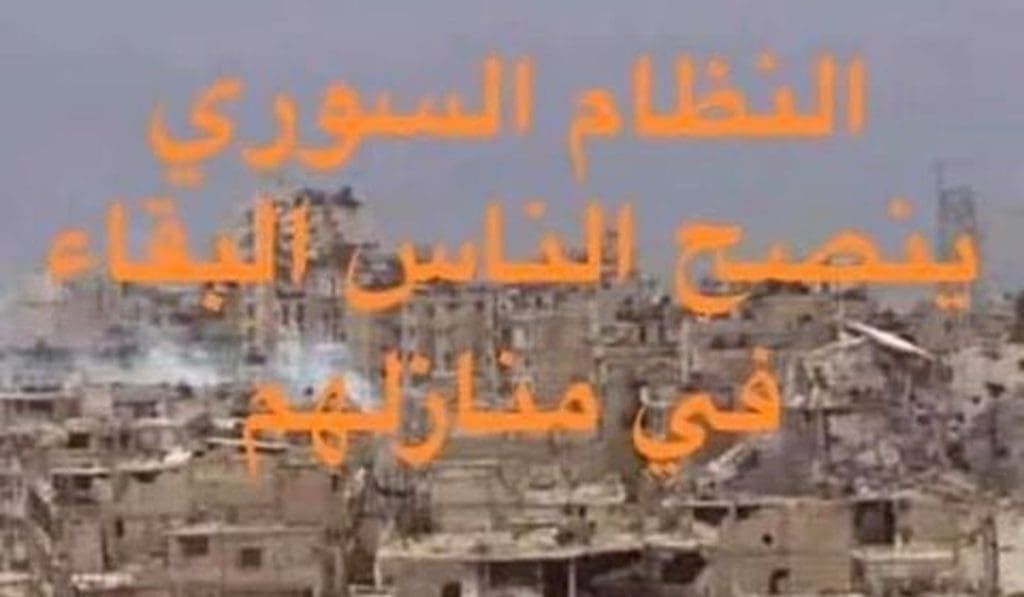

Featured image: dark humor at the outer limit of neoliberal fascism. A meme circulated among Syrians on social media in mid-2020, reading: “The Syrian government has asked people to stay home.”