Transcribed from the 24 January 2021 episode of The Fire These Times podcast and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h3d6oAGgmkY&w=560&h=315]

If you are a true internationalist you should support struggles against capitalism and authoritarianism wherever they occur in the world. Maybe you have more leverage to support struggles against your own state, but regardless of that you should do your best at least to speak out against oppression.

Joey Ayoub: Today we’re talking to Rohini Hensman. She is an India-based Sri Lankan labor activist, feminist, and independent scholar whose book Indefensible: Democracy, Counterrevolution, and the Rhetoric of Anti-Imperialism I reviewed some years ago and will be the topic of our conversation today.

In that book, she argues that the apparent anti-imperialism of many self-professed socialists amounts to explicit or implicit support for totalitarianism, fascism, Islamic theocracy, and—ironically enough—imperialism. She goes through the examples of Syria, Iran, Iraq, Bosnia, Russia, and Ukraine.

Some of you may know by now that this has been a concern of mine for a few years now, and I wanted to take this opportunity to bring it to a wider audience. So Rohini is on to explore how such a supposedly noble political position—anti-imperialism—can be so easily corrupted. I should say here that you don’t have to identify with any “ism” to find this topic informative. You just need to be someone who opposes authoritarian politics.

Rohini, your book asks a question that I know many of our listeners would have asked themselves: how has the rhetoric of what we might call anti-imperialism (very broadly understood) come to be used by various actors in support of anti-democratic counterrevolutions around the world?

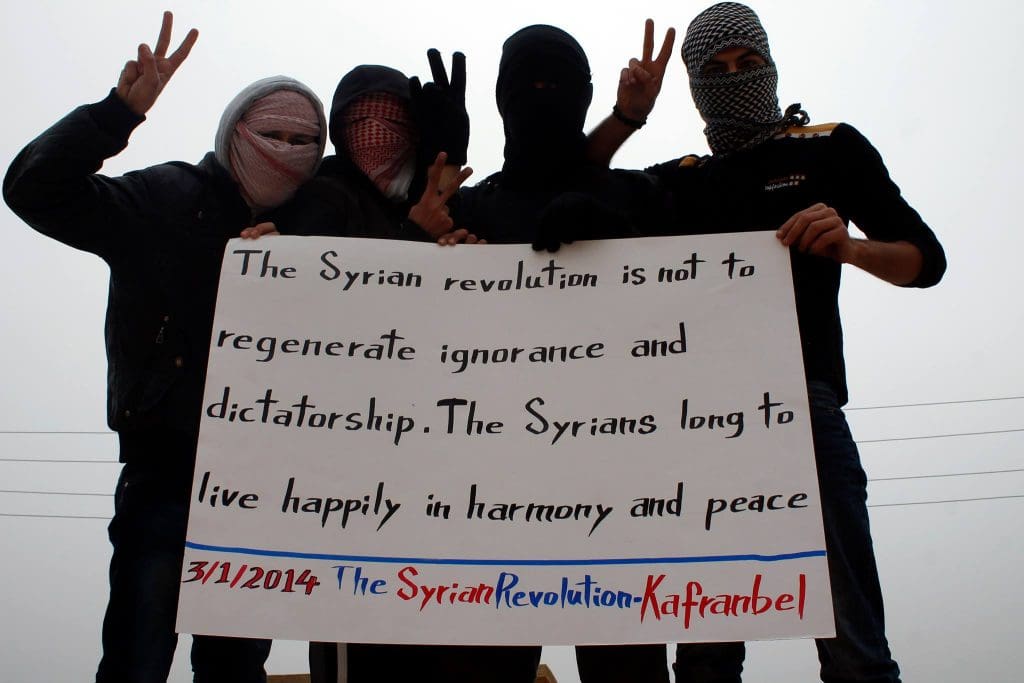

Rohini Hensman: I came to ask this question at a specific point in time, when the Syrian uprising was being crushed very brutally. One would have expected there would be an outcry from the left. Earlier on, when the Arab Spring started, at the end of 2010, the entire left welcomed it, very excited about the positive development. But very soon I realized that the response to the uprisings in Egypt and Tunisia was different from the response to the uprisings in Syria and Libya.

As the repression grew, it became more and more obvious that there was a significant section of the left which did not side with the uprising in Syria in particular, and which even was cheering on Assad. I found that really upsetting. At roughly that same time, other things were also happening. There was the Russian incursion into eastern Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea. Again, there was a section of the left which was cheering it on. That really set me off. I thought I had to understand, and help other people to understand why this is happening. It’s really a very negative development for the left to be taking these stances.

JA: Thank you for that background. To kickstart this conversation, how do you understand that question of Why? Why does this happen? What are some of the underlying causes?

RH: The original problem starts with what happened in the Russian revolution and then the counterrevolution that occurred in Russia, in spite of which large sections of socialists continued to treat Russia as a socialist country and the Stalinists as socialists. This carried on throughout the Cold War, where there were people on one side, the American side, supporting US imperialism, but on the other side there were equally horrific violations of human rights and imperialist domination of what were formerly tsarist Russian colonies. While that was going on, people were calling it socialism and communism. Of course, that’s a completely wrong idea from the standpoint I would take on what is meant by socialism or communism.

I call this wide section of people who support what became Putin’s Russia—which actually has no resemblance to what Russia was after the revolution, and is not even similar to Stalin’s Russia or its allies—neo-Stalinists, because they are no longer like the old Stalinists. They support everything that Russia and its allies do, regardless of how atrocious and oppressive it is.

But there is an even wider section of people who don’t necessarily support Assad or Putin but who more generally feel that the only thing to do is oppose western imperialism. This seems to me also a sort of strange stance to take. Because if you are a true internationalist you should support struggles against capitalism and authoritarianism wherever they occur in the world. Maybe you have more leverage to support struggles against your own state, but regardless of that you should do your best at least to speak out against oppression by other imperialisms or other authoritarian states, and possibly to take other actions such as demonstrating against them, and so on.

If you ask them why they don’t do this, there’s hedging. Ultimately these people set up a binary: if you don’t support these supposedly anti-US and anti-Israel forces, then it necessarily means that you are supporting US imperialism and Israeli aggression and so on. They don’t seem to understand that there is a possible third position where you oppose both. That’s a very common stance.

Finally, taking advantage of this, there are the despots and tyrants themselves, the authoritarian dictators and the imperialists on the other side who claim that because they are opposed to the US and its allies, they are therefore anti-imperialist. So the worst elements are also claiming to be anti-imperialist.

JA: There are three broad categories of this tendency, which you call pseudo anti-imperialism (I’ve called it “alt-imperialism,” Leila Shami called it “the anti-imperialism of idiots;” so many other terms have been used). It is a real problem on the left. It might sound like we’re focusing a bit too much on this relatively small minority or whatever, but the tendency goes beyond those who are card-carrying supporters of this ideology. There is a broader tendency which people adhere to, to various extents, and which can be just as damaging.

So just to reiterate the three categories for those who missed it: there are the tyrants and imperialists, there are the neo-Stalinists (whom many people just call tankies these days), and then there are those who “seem unable to deal with complexity, including the possibility that there may be more than one oppressor in a particular situation” [Hensman 2018]. They don’t understand that there can actually be two or more “bad guys.” I’ll mention that I did an episode of the Arab Tyrant Manual last year in which I was asked very similar questions by Ahmed Gatnash, who is a Libyan-British activist [transcript here –ed.]. One of the things I reiterated many times is this allergy, this hostility towards complexity.

One of the main takeaways I got from your book, and what I myself concluded from my understanding specifically of Syria (sometimes I can’t believe that it’s really been a decade) is that this alt-imperialism depends on “a West-centrism which makes them oblivious to the fact that people in other parts of the world have agency too and that they can exercise it both to oppress others and to fight against oppression; an orientalism which refuses to acknowledge that ‘Third World’ peoples can desire and fight for democratic rights and freedoms taken for granted in the West; and a complete lack of solidarity with people who do undertake such struggles” [Hensman 2018].

As a feminist too, I find support for these regimes quite obnoxious. All of them are extremely patriarchal and misogynist—horrific treatment of women, including women political prisoners; torture and rape used as a weapon of war. I find it really hard to take, this support for these regimes. Both as a long-time anti-imperialist and as a feminist, I find it quite repellent.

This is kind of a joke in the circles I am in now: everything that happens in the world is a conspiracy or a Western plot or the CIA has its hands in it one way or another. I’ve seen this tendency, and I’ll ask you to comment from your own background on this. I’ve seen it not just among Westerners. I’ve been at the receiving end of it—I’ve been called al Qaeda to ISIS, an agent of empire; sometimes they just call me a liberal because they think this is the worst thing they can call me. And I’ve gotten it from both Westerners in the West but also (in smaller numbers) from other Arabs in the Middle East. Even nominally anti-imperialist Arabs or Arab leftists specifically who reproduce alt-imperialism are deeply invested in this West-centrism, and are unable to view the agency of Assad in Syria or Gaddafi in Libya, ignoring things like Assad’s participation in the CIA torture program under the Bush administration, Gaddafi’s open and cozy relationship with Berlusconi, his assassinations of activists abroad and in Libya, and so on.

This, to me, is the other side of the coin of those who believe in US exceptionalism through military means. They don’t just reproduce the same logic, they reproduce the same narrative—they simply pick the other camp. It’s a campism, it’s a binary. And they don’t try to undo that binary, obviously. That’s the entire problem here. They don’t seek that third option.

This is my experience in the Arab world—would you mind bringing your own background into this?

RH: I came from an anti-imperialist family in Sri Lanka. Both my parents were committed anti-imperialists, and they tracked liberation struggles around the world. I grew up in that atmosphere. But that was part of a general support for democracy and against authoritarianism, wherever it came up, including in Sri Lanka itself. So I associated anti-imperialism with anti-authoritarianism and pro-democracy ideas. This is one reason I was so appalled at what was happening after the Syrian revolution.

As a feminist too, I find support for these regimes quite obnoxious. All of them are extremely patriarchal and misogynist—horrific treatment of women, including women political prisoners; torture and rape used as a weapon of war. There was a previous episode which I found equally horrendous, which was the Bosnian genocide. Then, too, there was a section of the left—including some mainstream people like Edward Herman, who was Chomsky’s associate and coworker—coming out very strongly in support of the Serb nationalists. Think of the horrific things: an actual genocide happening that included mass rape; rape camps (something that hadn’t been reported before) as a way to commit genocide that has not even been addressed today. There are victims who are still waiting for some kind of acknowledgment of their experience. So as a feminist I find it really hard to take, this support for these regimes. Both as a long-time anti-imperialist and as a feminist, I find it quite repellent, really, these tendencies.

There is also orientalism, as you mentioned. I would go so far as to call it racism. Imagine, there are these huge masses of people coming out in peaceful protest, and you say that they are being manipulated either by Islamists or by imperialists; you don’t give them the benefit of recognizing them as people who want democracy, just like you. No, they’re different. And yes, we find it even among our people, “Third World” people—I find it in India too, this writing off of uprisings as either Islamist or imperialist or both.

Earlier on at least, India was a staunch supporter of Palestine. Many on the left still support Palestine. Part of the problem is that they have followed discourse around the “axis of resistance” and therefore feel that those who claim to be part of the axis of resistance, such as Assad or Khamenei, have to be supported. For one section of the left, that is their motivation for supporting these people. Again, this is crazy, because Assad has actually bombed Palestinians in Syria. There are Palestinian political prisoners in Syria. The fact that he’s doing it to Syrians surely should move one to think: is he really pro-Palestinian if he crushes a democratic uprising this way? Is he supporting democracy?

That is one motivation. Another is a failure to identify with and empathize. In India there is a situation where ethnoreligious minorities, women, workers, the rural poor, and dissidents of all kinds including journalists, intellectuals, academics, human rights defenders—all are being suppressed in various ways. There is a similar situation in Syria, and one would expect that people who are facing this kind of situation in our country would sympathize with and identify with people who are being subjected to the same kinds of oppression elsewhere. But again racism comes in the way. They claim to be opposed to US imperialism; they claim to be against Israeli oppression; therefore you must support the oppressors, not the people rising up against them.

This is very weird, really. That’s why one feels so terrible about what happened in Syria: they are people like us who are being crushed. That’s what I would expect anyone on the left to feel.

JA: I had a very similar thought process in the past decade or so. My exposure to Syria was through Lebanon, since I grew up in Lebanon and I’m Lebanese. There’s a very specific context there. To some people, Syria is the ally that helped Lebanon resist against Israel. To other people, Syria was the invader in 1976. The reality is it’s a combination of both, and it’s also beyond both. The support against Israel, for example, was conditional. It had its limitations; at times it was contradictory, and it erases the fact that in 1976 Hafez al Assad’s regime invaded Lebanon to oppose the Palestinian and leftwing nationalist factions.

The year after the invasion, in 1977, Kamal Jumblatt was assassinated; he was the leader of that coalition of Palestinian and leftwing factions (and a few nationalist factions) in Lebanon. Their main opponent was the Christian rightwing nationalists at the time, who were broadly aligned with Israel. The people who bring up the eighties do so without bringing up the seventies; people who mention Hezbollah’s role against Israel in the nineties then ignore events like in 2008 when Hezbollah took over parts of Beirut and Mount Lebanon, and obviously ignore Hezbollah’s military intervention in Syria since 2011, especially 2012-13. This suggests to me that they are willing to go against their own history.

There is the example of Lebanese and Syrian communists. There are many of them, and there is no one tendency. But those who were opposed to the authoritarian regimes in Lebanon or in Syria were crushed—exiled or killed. Those who put that aside or have openly allied themselves with these regimes were more or less allowed to operate, because they were defanged; they don’t really pose a threat. In Lebanon (and in Syria as well, but that’s a different story), prominent Marxists and intellectuals in the south, like Mahdi Amel, were assassinated by what would end up becoming Hezbollah. These were people who were part of the community. They were Shias from southern Lebanon who dominated rural and working class politics in southern Lebanon especially. I suppose Gramsci would call them organic intellectuals; there were a lot of these coming up.

There is the example of Lebanese and Syrian communists. There are many of them, and there is no one tendency. But those who were opposed to the authoritarian regimes in Lebanon or in Syria were crushed—exiled or killed. Those who put that aside or have openly allied themselves with these regimes were more or less allowed to operate, because they were defanged.

Now, it’s a broader story. I did an episode with Ziad Majed, who was part of that world for a long time, on the fifteen-year commemoration of the assassination of Samir Kassir—2 June 2005. He was a leftwing Lebanese-Palestinian-Syrian involved in liberation struggles in both Palestine and Syria, and he saw them linked as well as linked to the struggle in Lebanon at the time against the Syrian government. That was after the liberation of southern Lebanon in 2000. Between 2000 and 2005 is when all of this happened, mostly.

This is all to say that there are still people today in Lebanon—not many, and in general these numbers are not very high in the first place—who would call themselves communists but who sort of gloss over the fact that Hezbollah did this to communists. It is similar to some Iranian anti-imperialists glossing over the role of Khomeini in crushing Iranian communists. These people would often fight with other Iranian communists who opposed Khomeini for those specific reasons (and Khamenei these days for the same specific reasons).

It goes back to your initial point that being uncomfortable with complexity. Being willing to go with the flow to embrace one narrative that’s easy to digest does incredible damage. I’m barely scratching the surface here. I’ve mentioned assassinations and I’ve barely started.

I wanted to ask you again about the Sri Lankan context, because probably most people listening to this don’t know much. Would you mind mentioning how anti-imperialism as a rhetoric, as a narrative, was used and maybe is still being used by the ruling establishment in Sri Lanka to whitewash their own politics?

RH: Most people know there was a civil war in Sri Lanka. There was oppression of the Tamil minority in Sri Lanka. There were many armed groups but the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam became the dominant one. They were on the other side of the war. Huge violations of human rights occurred on both sides. It ended in 2009 in a most horrific way. The Tamil Tigers, basically using Tamil civilians, hundreds of thousands of them, forced them to retreat as the Sri Lankan forces were advancing. At that time, Mahinda Rajapaksa was the president. His brother Gotabaya Rajapaksa was the army commander. And they showed no mercy. They knew that most of these people were civilians. They knew the Tigers were forcing them to retreat. And still they went ahead. They bombed hospitals, they bombed breadlines. At the end of the war at least forty thousand (and some people put it at many more) civilians were killed when the Sri Lankan forces finally defeated the Tigers.

Of course, not all Sinhalese were in favor of what was happening. And the government was clamping down on people who objected. At the end of the war, it was mainly Western powers in the UN, in the human rights council as well as the security council, arguing that there should be an investigation into war crimes at the end of the war in Sri Lanka, and people should be held accountable. In that context, Mahinda Rajapaksa claimed anti-imperialism, opposing this demand for accountability for war crimes; anti-imperialism was the grounds on which he opposed it.

Oppression had been heaped on Tamils. Apart from those who were killed, hundreds of thousands were interned in military camps. It was horrendous. Their relatives outside didn’t know who had died, who had survived, who had disappeared, nothing. At this point you would expect anyone to support a demand for at least an investigation, if not some degree of accountability. They should also have held the Tigers to account for their atrocities too. But no. Now, I would expect China and Russia to object. But what I found especially disturbing was the Pink Tide people in Latin America. They were supporting Rajapaksa. The Evo Morales regime even gave Rajapaksa a Peace and Democracy award. At that point I must say I lost my respect for them. If they didn’t know what had been going on, they should have. To honor someone who has been slaughtering civilians is really beyond the pale.

That was my personal experience of the way anti-imperialism has been used by criminals, essentially—people responsible for mass crimes—to cover up their crimes. And the way other people accepted it.

JA: I was thinking about the gendered aspect of it, which you already brought up. I feel that by and large, this tendency that we’re calling alt-imperialists, tankies, pseudo-anti-imperialists—authoritarianism on the “left” broadly speaking—it doesn’t take too much to notice that they tend to be men.

What is the link between masculinity, misogyny, patriarchy, these forms of power and domination, the forms of masculinity that are authoritarian and toxic—what is the relationship between these things and this specific form of “anti-imperialism?” How would you understand it? I don’t think enough attention has been paid to the gendered component of it.

I’ll include this as a parenthesis: Lebanon also had a civil war, of course, 1975 to 1990, and the crimes that were committed during that war, which included rape and torture and everything else, were essentially written off in 1990-91 through an amnesty law. Long story short it’s how the warlords who were in power during the war ended up in government after the war. They are all men, obviously. And Lebanon, although there is a very vibrant feminist movement, remains a hyper patriarchal society.

By and large this form of “anti-imperialism” draws its political energy from existing patriarchal structures and from existing misogyny, and we can add transphobia and homophobia that also come with it. It can be very obvious. As soon as you include feminism as a framework, the links are very obvious. It can be very jarring to see people, often men (but not always; there are also women who participate in this), calling themselves feminists while reproducing this authoritarian logic which ultimately is linked in one way or another to patriarchal domination and violence.

How would you see this link between masculinity and “alt-imperialism?”

In the patriarchal family, the last resort to enforce the subordination of women is violence. There is a huge amount of violence against women, which may or may not be acknowledged, and women fighting against it are often suppressed and repressed. I would see this as a key feature of all these regimes.

RH: I have argued elsewhere that a key pillar of any authoritarian state is the authoritarian patriarchal family. All of these authoritarian regimes, whether they are on the protofascist right or whether they claim to be on the left but are in many ways equally oppressive, depend to a large degree on suppressing women. In the patriarchal family, the last resort to enforce the subordination of women is violence. There is a huge amount of violence against women, which may or may not be acknowledged, and women fighting against it are often suppressed and repressed. I would see this as a key feature of all these regimes. Because they are authoritarian, they do rely on patriarchy, misogyny, and in many cases homophobia—the so-called “family values” which see women as subordinate, girls being less valuable than boys, and so on. And violence against women has been permissible.

So there’s no puzzle here, really. I would agree with you that this kind of masculinity is very compatible with it, even where there are a few women who participate in this—they have also succumbed to this logic of aggressive masculinity.

JA: I would add another example, the figure of Hezbollah’s leader himself, Hassan Nasrallah. If people just listen to his speeches—and a lot of them are subtitled in English—his comments on feminism and on people who are LGBTQ (which he doesn’t even recognize as existing) are so rightwing that they make some rightwing figures in places like Europe and America look liberal in comparison. They are extremely ultraconservative. He literally views feminism as a Western invention and a Western import—that this comes directly down the line from Khomeini and Khamenei is very obvious two people who study these two figures and others around them.

For me personally, it ends up becoming like a dissociative state: seeing on one side people saying one thing and then as soon as they cross the border, so to speak, to Lebanon or to Syria or Iran or wherever, then they put on a completely different hat, which is identical to what someone on the far right would say. Syria for me was the case study par excellence of this happening. I documented this, that’s how meticulous and obsessive I was about it: if you look at which side of the spectrum the Western politicians are on who would go to Syria (and to Damascus specifically, invited by the Assad regime), it’s seventy to eighty percent far right, and the remaining twenty to thirty percent are “leftwing” “anti-imperialists.” This includes American politicians, Spanish politicians, some in the UK and so on. I can also name leaders on both the left and the far right in France who have made almost identical statements when it comes to Bashar al Assad.

In the last section of your book, you list five ways that anti-authoritarians can use to counter the tendency that we’ve been talking about here. Can you go through them a bit?

RH: The first one is to pursue the truth and tell the truth. A lot of the people who swallow the kind of disinformation that’s been dished out—I don’t blame all of them, because it’s really hard. It takes a lot of time and effort to find out for yourself what is actually going on. But the people who create this disinformation, who put it out, who create bots that repeat it ad nauseam and so on—that is a counterrevolutionary thing to do. Regardless of what you call yourself, that is rightwing. Because it completely denies the truth—you see what’s happening in the US right now—and therefore actively helps oppressors carry on oppressing.

It is the task and the responsibility of those of us who are opposed to this kind of oppression to find out the truth and to find ways of getting it out, and telling people that it’s not a simple matter of everything that’s put out in the Western media is wrong and everything that’s put out in the anti-Western media is correct. No, you have to use your mind and look at them all critically. You will find inconsistencies in stuff on both sides. But there’s so much similarity in the stories about weapons of mass destruction in 2003 to justify the war on Iraq on the one hand and the stories denying the chemical weapons attacks on Syrians. It’s so similar. In both cases it helps an aggressor kill and maim and displace innocent people. It is a profoundly counterrevolutionary and criminal thing to do. You are becoming a part of the crime.

The second one is to bring back humanity and morality into politics. This may sound wishy-washy, but it is absolutely necessary. As Howard Zinn said: in a world of conflict, there are victims and executioners, and it’s the responsibility of thinking people not to be on the side of the executioners. Unfortunately this is what people who I call pseudo anti-imperialists are. They are taking the side of the executioners and completely ignoring—or in some cases actually vilifying—the victims. There are the stories against the White Helmets, who are rescue workers and have saved thousands of lives. Many of them have been killed in the process. And you vilify them as Islamist or imperialist. And you vilify the victims who they are trying to help, who are being bombed. You call them terrorists as well. That is totally evil. People—not just socialists, but anyone with any kind of humanitarian instincts—should not participate in that, and should see what is wrong with that.

The third one is democracy. Here we have a problem on the left that is encapsulated in the term bourgeois democracy. Somehow democracy is associated with capitalism, and therefore it is dismissed, it’s not what we fight for. But this is completely untrue. I have examined it, gone back to Marx and Engels and so on, and this is not at all how democracy was seen. In fact, democratic revolution was the first step towards a socialist revolution. So this is a profoundly wrong attitude towards democracy. We should support struggles for democracy wherever they are in the world. That is one step towards socialism.

We have to critique not just the Stalinists—they are the worst in some ways, because they justify an ultra-authoritarian dictatorship which crushed democracy completely—but there are also some on the left who may even be anti-Stalinist but still have this suspicion against democracy and don’t see it as their duty to support democratic struggles, only seeing revolution as coming from above in some way, by a party or some section of elite, and not by working people as a mass.

This leads into the theme of internationalism, which is the fourth one. Capitalism is an international system. The world is increasingly globalized. Whatever problems we face, from poverty and unemployment to global warming to refugees—the whole idea that you can tackle any of these things simply within the borders of one country, your own country, is wrong. What is happening in the rest of the world is of profound importance to your own struggle. That is, elsewhere there is some dictatorship which is crushing democracy, and crushing democracy means crushing trades unions, which means crushing workers’ struggles, women’s rights struggles. Ultimately that is going to affect you. Ultimately, to oppose capitalism you will need the help of those people who are being crushed. So it is absolutely necessary, and not a luxury, that you support struggles for democracy and human rights wherever they happen in the world. That is part of the struggle for socialism.

It has become extremely evident, especially from the example of Syria, that any international intent to help a population of working people under a murderous genocidal assault will need to deal with the fact that any such help can be blocked by the UN security council’s permanent members who will not allow any such assistance. Even food and medicine—forget about any kind of military assistance—could not be delivered to populations under siege, people who were being starved.

Whatever problems we face, from poverty and unemployment to global warming to refugees—the whole idea that you can tackle any of these things simply within the borders of one country, your own country, is wrong. What is happening in the rest of the world is of profound importance to your own struggle.

There are institutions that can be made use of, like the international criminal court, though again there is the problem that you have to go through the UN security council unless the country is signed up and has their own statute. Still, although we try as much as possible to build solidarity from below, there are some things that ordinary people like us can’t do. We can pursue the truth. We can publicize the truth. We can hold meetings and demonstrations in support of people who are being assaulted. But most of us are not really equipped to supply them with what they need in terms of support to defend their lives. And by opposing any attempts to help them, you become complicit in what is happening to them.

I’m thinking—and I may be wrong here—of the demand for no-fly zones in Syria, which many Syrians were asking for. How these would work I don’t know. But we have to at least look at that. People who are being bombarded, who are being gassed, who are being besieged and starved and killed—we have to do something, I think, which we can’t do as civilians. Something needs to be done for them. And for that we need some institution to call upon. To oppose that kind of initiative outright is wrong. Then you become complicit in the slaughter.

JA: One of the things I’m trying to focus on this year is the commemoration of the fact that it’s been ten years since the start of the uprisings in the Middle East and North Africa. But one of the negative things that has happened since then is the rise of authoritarianism throughout the world. I don’t want to be Arab-centric, either. It’s not just about the Arab Spring; it’s not just about the Middle East and North Africa of course. There are other factors. But part of the problem we’re facing today is the fact that there have been no consequences for people who have committed war crimes and crimes against humanity.

This doesn’t just include Arab dictators. It doesn’t just include Putin. I’m also referring to Western leaders in various capacities as well. But there’s something specific about what happened in Syria and what’s been happening in Syria, and the consequences on the world. Yassin al Haj Saleh called it the “syrianization” of the world, pointing towards the normalization of impunity. Especially in the past four or five years (and indeed we’re recording this just a couple days after the storming of the Capitol in the US), we’ve seen this extremely toxic combination of things like online disinformation, the messed up algorithms that social media giants use, the toxic masculinity, the sort of thing we see in Trump—all of these things, in addition to the environmental pressures that are increasing, and in addition to the economic crisis, which most likely will continue for the foreseeable future, especially as we’re still dealing with and reeling from the consequences of the global COVID-19 pandemic, a big part of the story is how the world has reacted, or not reacted, to the Syrian crisis.

This is perhaps most obvious in the Arab world and Europe. I’m thinking of “Fortress Europe,” the raising up of walls—while criticizing Trump’s plan, they are doing the same stuff to their own borders. Some of the militarized tactics that the Europeans use are worse than what the Americans use. I have an upcoming guest from the Border Violence Monitoring Network in the EU. They have recently published something called the Black Book of Pushbacks. It’s this massive volume of documented pushbacks, when border police literally push refugees and asylum-seekers and migrants back into a non-EU country where they don’t have to deal with them or think about them. This long document is being distributed in the EU among parliamentarians and so on, and one of the things it reveals is that in addition to the already-existing xenophobia and racism and nativism and nationalism and all these things we see pretty much everywhere in the world, there’s a very specific hatred and fear towards Syrian refugees. This is one consequence of the Arab Spring on Europe.

In the Arab world, the main result, with the exception of Tunisia which had its own trajectory, is for governments to point to Syria in order to discourage people from demanding too much. They can tolerate various forms of dissent, but this changes from place to place. In Iraq it depends which region; in Egypt (and in the Gulf region as well) it tends to be zero tolerance—it depends on your region but it also depends on your class, what kind of clout you have in different forms of financial or cultural capital that might protect you from certain repercussions. But they use Syria: “Well, at least we’re not Syria. At least it’s not as bad here as it is in Syria.” You don’t hear this as much any more in Lebanon because things have gotten so bad since the explosion and the crisis and everything, so people don’t seem to respond to it in the same way. But it has worked for the better part of a decade to use this fear tactic.

So my question to you after all this is: how would you describe the impact of the 2011 uprisings and revolutions on your own politics?

RH: I’ve learned a lot about the countries involved, including Iraq (which I thought I knew something about earlier because of opposition to the Iraq war, but it’s a much more complex situation after the war). You are right about the completely negative results, around the world, from the way there has been no accountability for the repression of them Arab uprisings. There was so much positive feeling when they started! That’s one of the things I learned: how in the aftermath of the US invasion of Iraq, the US and UK sectarianized the country and (this is very bizarre) handed it over to Iran-backed Shia politicians and militias, which in turn worsened the sectarian conflict in Iraq and allowed ISIS to form.

I was not aware of these aspects earlier, nor was I aware that from the beginning, Khomeini had his sights fixed on dominating Iraq. I didn’t know; I always thought of Saddam Hussein as the only bad guy in the Iran-Iraq war. I didn’t realize that after two years it could have ended if it weren’t pushed further by Khomeini for another six years in which over a million people died.

Of course now Iraq has become much more fundamentalist-dominated; I did not know the complexity of problems Iraqi women face as a result of this. I have learned about the incredibly complex character of what is going on in the countries I looked at in the book—again including Iran—and the incredible courage of the people standing up to the state in these places even with the horrific repression that they are met with. In Iraq just now, the uprising was again crushed in very brutal ways. One has to really admire the people fighting against sectarianism and authoritarianism in these countries, and look for better ways of supporting them.

The reaction of the pseudo anti-imperialists is so toxic, because on the one hand you would expect the rightwing to support these authoritarian regimes, and they do—but you would also expect a united leftwing response against them, and it is not there. The so-called left is completely divided and confused. On one side there are people who do support the uprisings and the democratic aspirations of the people in these countries. On the other hand there is a section who support the dictators, who support the oppressors, and still call themselves socialists. The way in which the Arab Spring has progressed brought this home to me in a very stark and heartbreaking way. It still breaks my heart to think of Syria and what happened there. It’s horrendous.

JA: Rohini Hensman, thanks a lot for your time, this has been a fascinating conversation.

RH: Thank you.

Featured image: painting by Iraqi artist Hani Dallah Ali