AntiNote: This essay by Aida Baghernejad, a researcher in Berlin, was published only a few days after a racist gunman attacked two hookah bars in Hanau, Germany, killing nine people. Today, a year after the attack, her words—her frustration, pain, and rage—feel that much more potent. Have we made any progress at all? Or are we even further down the spiral into abject reactionary barbarism, still dressed for church?

Printed with the author’s kind permission.

And the End Result Is Hanau

On growing up in a racist country

by Aida Baghernejad for SPEX (Germany)

24 February 2020 (original post in German)

In Germany, it’s already business-as-usual again and society has learned nothing.

So is everyone back to business-as-usual after the murders in Hanau? Have they once again filed away the attack as another “deranged lone wolf,” perhaps now embellished with the remark, “radicalized online?” Have the victims once again fallen down the memory hole? Are Gauland, Weidel, Meuthen and company already back on the talk shows? Is Bild back to printing stuff about the bad lazy “foreigners,” Hans-Georg Maassen on the dangerous left, Ulf Poschardt on the correlation between freedom and “wiggle room?” Have the victim’s families once again been left alone with their grief, their loss, their pain, their fear? And when someone among them resists, demands an investigation, asks why the police and federal law enforcement hadn’t had the murderer on their radar, do we find this person once again somehow a little too shrill?

In other words: has society once again learned nothing—I mean really absolutely nothing? Do the police say, and journalists write, “xenophobia” when the word they’re looking for is “racism?” Because that’s precisely the point: we, people with (assigned) “migration backgrounds,” racialized people—we are seen as strangers, outsiders. It doesn’t matter how long we’ve been here; it doesn’t matter what we contribute, how hard we try to fit in, how much we—to use some people’s (above all conservative politicians’) favorite word—integrate? None of this changes anything about the fact that the place we live will never be our home in the eyes of the so-called majority society.

You don’t belong here—not really, not completely.

I was born in 1988 in a town not far from Hanau, and my cries brought down walls (to paraphrase Hendrik Bolz a.k.a. Testo from [German rap duo] Zugezogen Maskulin). As I was growing up, sheltered and protected, the country around me was aflame. I was two years old when Amadeu Antonio was murdered; three when the mob in Rostock-Lichtenhagen stormed asylum seekers’ housing; four when people were burned to death in their own home in Solingen. How did society respond to these and all the other atrocities? With human chains and candlelight. And with the tightening of asylum laws as a reward for the murderers. Racism as a social problem was shifted onto a foreign Other, namely East Germany, while West Germany maintained its self-image as superior.

Of course East Germany has a racism problem. A big one, as last year’s discourse around the “baseball bat years” made very clear. What else is to be expected when half the heirs of Nazi dictatorship are comforted over decades with the reassurance: You are free of blame; fascism was only “over there”—only to greet reunification with flag-waving nationalist ecstasy? But West Germany is not blameless: until 1980, there were no comprehensive records kept on victims of rightwing terror. There are rudimentary numbers, but one must assume that the real totals were much higher. Only in the 1980s—with the Oktoberfest attack in 1980 to be exact—was there even a gesture of attention to rightwing terrorism. But a lot of people were dying before that. In Hamburg. In Erlangen. In Gündelback, Norderstedt, Hannover, Berlin, and so many other places. At the hands of “deranged lone wolves” who went berserk and killed their neighbors while yelling racist slogans. Or organized groups like Wehrsportgruppe Hoffman and radical rightwing motorcycle clubs.

Integration until burnout and beyond

I was lucky enough to be born into a privileged family. I was spared the open hostility that so many other BIPOC speak of. But microaggressions, the little needle pokes—they happened daily. Frequently bestowed as compliments. One wound, still today not fully healed, was inflicted by a supposed friend: “From your voice on the phone, it’s impossible to tell you’re a foreigner!” She had grown up the child of German hippies in Greece and had only been in Germany a few weeks at the time. But the “foreigner”—that was me! Not her. It could never be her.

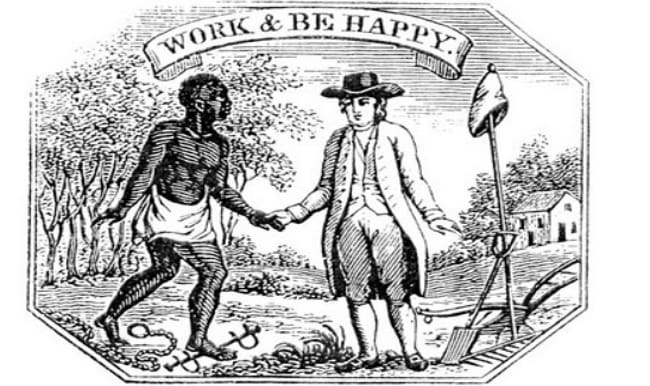

I can almost understand her—she wasn’t the one being targeted by the posters that screamed at us on the street: “The boat is full!” on a red background, or “Safe travels home!” above a cartoon of people sitting on a carpet like the ones we had at our house. We tried to laugh about it, but the needles hit their mark anyway. You don’t belong here. Not really. Not completely. Even a German passport, which I—as a person born in Germany—only received as a teenager, didn’t change anything. In Hessen around this time there were signatures being collected against double citizenship. Against people like me. At the citizens’ assemblies, as eyewitnesses recall, were people who showed up asking, “Where do I sign my name against the foreigners?”

Maybe it would help, then, to be better than the rest? Faster? More productive? Strive to integrate until well past burnout? Fatma Aydemir writes about this in her fantastic essay “Arbeit” [“Labor”] in the collection Eure Heimat ist unser Alptraum [Your Homeland is our Nightmare]: “Perhaps the abiding condition of exhaustion is for many simply so normal, stretching over generations, that it cannot even be diagnosed. Perhaps speaking about mental health crises is seen as a weakness among those who must learn to be especially strong in order to survive in this society.”

This is precisely what happens under this constant pressure to justify our existence: it makes us sick. It sneaks into our brains, binds our self-worth to our productivity, and tricks us into thinking everything is fine. If you contribute something, if you are integrated, if you surrender, then you belong. That is the prize at the finish line: finally being “normal.” Finally not being judged and categorized long before you’ve even opened your mouth.

No passport, no title, no capital can protect us.

But this is nothing but an illusion. You will never be like the others. You will never know whether you finally did everything right in order to belong. A tiny voice will always whisper in your brain: was I not let into the nightclub, even though all my friends were, because I’m just not cool enough or because I look different? Was I turned down for that job because the other applicants were better qualified, or because my surname is too complicated? Did the property manager not get back to me because the apartment was already taken or because I sound like a foreigner? Do my white peers get support and job offers because they’re just better, or also (or only) because it never occurs to well-meaning people in positions of power to work through their racist biases, and my skin and hair color carry negative connotations and therefore I will always be judged more harshly, and cannot permit myself the same mistakes that others routinely make?

The white supremacist capitalist patriarchy that bell hooks writes about also exists within people who mean us well. They claim to “see no color,” and thereby shut their eyes to the reality of the world: that they can sail on through, where we must pick our way through brambles. They shut their eyes to the discrimination and the real danger we are confronted with. They can forget that every word that comes out of Alexander Gauland’s mouth, every Alternative für Deutschland campaign poster is directed at me and my family. No passport, no job title, no class position, no achievement will protect us from constantly being seen as outsiders, as those who do not belong. I don’t have to frequent hookah bars to understand the message of the Hanau terrorist and those who stoked his hatred. My New Year’s party could be a target—our weddings, our festivals, any place where we permit ourselves to meet with our communities, to honor our traditions, to recharge for the next few days of navigating a society that always regards us with suspicion.

A friend of mine works with Holocaust survivors who have dedicated decades of their lives to repeatedly bearing witness, even today, with every ounce of strength they have. Talking about what happened. Recounting how suddenly their home places started seeing them as the monstrous Other. Remembering and retelling it so that it never happens again. Yet when I saw this friend recently, she told me that the present political situation has these survivors in despair. Their words have meant nothing, they think. One is even hoping to die soon so as not to have to see what the world might be facing. It broke my heart to hear this, but today I understand them. It keeps getting closer, more frequent. Supposedly cultured words cloak the racism, reversing victim and offender. And the end result—the end result is Hanau.

Translated by Antidote

Featured image source: Seebrücke Frankfurt (Twitter)