Transcribed from the 13 April 2021 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

They built what I call a transcontinental defense of unfreedom, because they knew that one unfree institution depended on the other. And they were successful.

Chuck Mertz: The story we’re told is: the west here in the United States was never really touched by the sin of slavery, it was never sullied by the ‘peculiar institution’ which was entrenched in the southeast part of the country. Being free of such a stain, the west was a perfect place for the rough and tough individualistic icon of what it meant to be American in the United States and defined so much of what we are today.

It turns out none of that is true. The master class had succeeded to some extent in making US slavery transcontinental. They even had global plans that were being set in motion.

Here to help us reexamine and reconsider what slavery really was in the United States, nineteenth-century political historian Kevin Waite is author of the book West of Slavery: The Southern Dream of a Transcontinental Empire.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Kevin.

Kevin Waite: Thanks, Chuck, it’s good to be here.

CM: You write, “As the nation careened towards civil war, a pair of curious tunes rang through the streets and saloons of Los Angeles.” I tried to find these on YouTube yesterday and I’m really glad I couldn’t. The two songs are called, “We’ll Hang Abe Lincoln in a Tree” and “We’ll Drive the Bloody Tyrant from our Dear Native Soul.”

“They were not composed in California but they quickly found favor with the town’s rebellious element in the spring of 1861. Through these songs, white Angelenos taunted the region’s outnumbered Unionist population and gave voice to their deep-seated Southern allegiances.”

This is after California became a state, eleven years earlier in 1850. So do these Confederate sympathies in California reflect any level of long standing discontent with being part of the Union? Or was this anti-Union sentiment caused by the events that were leading up to the war?

KW: Truth be told, I have no idea what those songs sound like either, and I guess I’m sort of glad too. I would say the long standing sentiment in California was a sentiment in favor of slavery. A lot of white Californians, especially in the southern part of the state, were from the South originally, and they supported the institution of slavery. So when eleven slave states seceded from the Union and started the civil war in 1861, they wanted a piece of that action. That’s why they were singing these songs, and that’s why a lot of them actually fled California during the war and enlisted in Confederate armies.

CM: You write, “Californians paraded Confederate symbols through public spaces across the state. They cheered Jefferson Davis and his generals. They bullied federal soldiers stationed at military outposts, and they conspired in ways big and small to turn California against the United States.”

How popular was this rebellion? And when it comes to taunting at military outposts, was there ever any response by the Union military?

KW: This sentiment was pretty popular. I should say from the outset that California remained loyal to the Union, partly because there were enough federal soldiers in the state to put down these pro-Confederate demonstrations. But it was touch-and-go for a while. Even when there was overwhelming force in places like Los Angeles, these secessionist hooligans (for want of a better term) still pressed the buttons of federalist soldiers. They engaged in fistfights with them, they threw one Union supporter from an upstairs balcony. There were a couple casualties in these encounters with soldiers throughout California. I guess we could call some of those casualties the westernmost of the civil war.

CM: You write, “White Angelenos had no discernible tyrants to drive from their native soil in the spring of 1861, as they claimed in their rebel anthem, but they did express a deep sense of kinship built over the preceding decade with the slaveholders of the South.”

How was that kinship built? And was it an intentional project of the South to court the west to their side prior to the civil war? You mention political patronage as well, and because we’ve had a political patronage system here in Chicago for a very long time, I can’t help but wonder if this was a kind of laboratory for that kind of political patronage. So how was that kinship built, and how did that political patronage work?

KW: That’s a really good way to put it, Chuck—the west was really a laboratory for all sorts of pro-slavery schemes. Like you say, there were white Southerners who were actively courting support in the far west, in California and in New Mexico particularly, because they knew that they needed political power, and they needed votes in congress. All white Southerners were really concerned about their declining share of the nation’s total population, and they thought if demographic trends kept going this way, they would be a political rump. It sounds like certain Republican concerns right now. But they knew they needed to cultivate allies outside of the the South, and they saw California as a likely partner, because California—even though its population was probably only a third white and Southern—it voted with the South on a number of major political issues.

Like you say, they used political patronage to lure the west into the pro-slavery Southern political orbit. A lot of people don’t think of patronage today because we have a professional civil service, so it’s not as important. But in the 1850s, patronage was big business. These were some of the highest paying jobs in the state of California. You were more likely to make money as the collector of customs in San Francisco than you were mining for gold outside Sacramento. This was the way to get ahead. So these white Southerners formed a powerful, well-oiled political machine and they put all their friends into high places in these patronage offices.

The customs house in San Francisco was so packed with white Southerners on federal sinecures that it became known as the Virginia Poorhouse. This is where a lot of Virginians and other Southerners went to get rich in California.

The American cotton trade was far too lucrative for the major European powers to give up. They scolded slaveholders on the one hand while taking their cotton with the other.

CM: Back in 2016 we spoke with the historian Andrés Reséndez about his book The Other Slavery: The Uncovered Story of Indian Enslavement in America, which was a National Book Award finalist. Andrés writes about the enslavement of the Indigenous that was conducted by the conquistadors and, following them, in the Spanish colonies throughout Mexico and in the western and southwestern United States.

Did Indigenous enslavement affect the way the west viewed slavery?

KW: Absolutely. That’s a great book. If you wanted to own the labor of other people in the 1850s in the American west, there were all sorts of ways to go about doing it. You could bring African-American chattel slaves with you, and plenty of Southerners did. But the easiest way to get unfree labor was just to buy Native labor or ensnare Indigenous people in lifelong cycles of debt to make them your peons.

The numbers are really tricky to get at, because nobody was keeping careful records of this, but it’s estimated that between 500 and 1,500 enslaved African-Americans were taken into California during this decade—but thousands, tens of thousands of American Indians were ensnared in all sorts of involuntarily labor relations.

CM: You also write about a problem with the categorization of slavery: when we only look at, let’s say, Native American slavery, or we only look at the enslavement of those of African descent—what do we miss in our understanding of slavery when we have them separated in these different categories?

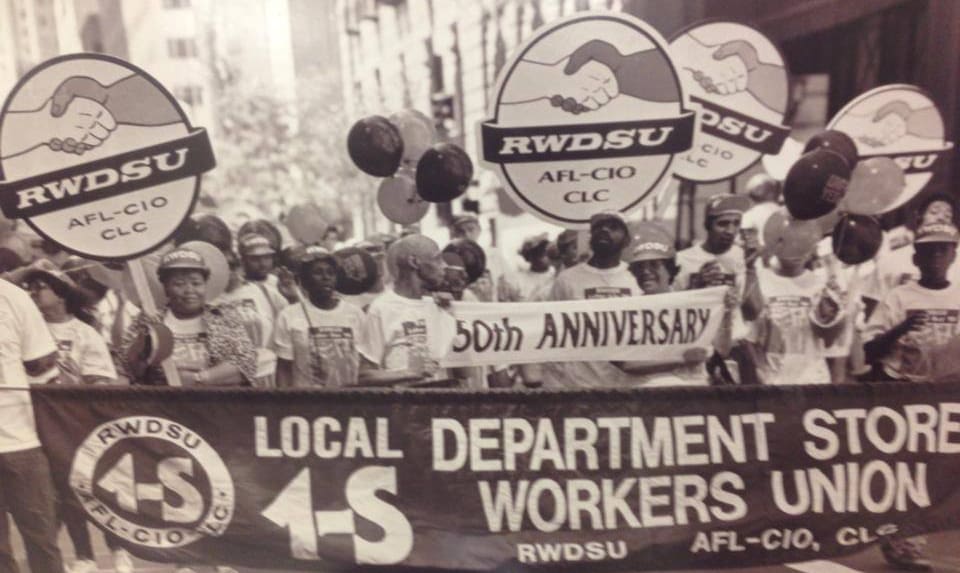

KW: That was well-said, Chuck. We know so much about African-American slavery in the South, and we still need to know more, but there’s a great literature on it. And there’s a budding literature on Native American slavery in the American west (Andrés is at the forefront of that). But we never really consider these two types of slavery within the same narrative frame. They belong to two separate bodies of historical research.

I try to put them in conversation, put them in the same frame, and see what happens. The biggest slaveholders in the United States at the time, the guys in the South, thought really seriously about Native slavery and what it meant for them. They regularly compared plantation slavery in the South to these coercive labor relationships in the west, and thought their system was clearly much better. But when anti-slavery Northerners tried to outlaw Native slavery in the west, white Southerners rallied in defense of it, because they knew if Native slavery were outlawed, it would be the lead domino to fall in a process that might threaten plantation slavery in the South.

They built what I call a transcontinental defense of unfreedom, because they knew that one unfree institution depended on the other. And they were successful. Unfree Indian labor wasn’t outlawed before the civil war. In fact it took decades after the war and after the thirteenth amendment for Indian slavery to be stamped out in the west.

CM: You write, “The American master class was more formal and far-reaching than previously imagined. Historians in numerous important works have tracked slaveholders’ expansionist projects in the Atlantic world. We now understand how American Southerners, through diplomatic influence, commercial power, and direct assaults on foreign soil, extended their imperial agenda across this swathe of the globe. Yet planters’ horizons could never be confined to a single ocean basin: while they operated primarily in an Atlantic world, slaveholders lusted after a transpacific dominion.”

Was the South, prior to the civil war, in direct competition with the Union, long before there was a Confederacy? And were the Union and the South engaged in parallel imperial wars prior to the civil war?

KW: I think the latter is more accurate, Chuck. Southern slaveholders knew they needed the power of the federal government, and they needed the power of Northern shipping in order to make money. It wasn’t until 1861 that they thought this bargain was no longer worth keeping. But when they looked to the Pacific, they saw the plantation economy of the South and the North’s industrial and martial economy as partners in the same agenda, and they wanted to extend the cotton trade to China. They were relatively successful in doing that.

Cotton was America’s leading export to China through most of the antebellum period. We forget this, because the China market wasn’t huge at this time. But cotton was number one for the United States, and slaveholders were all about the Chinese market because they saw hundreds of millions of potential consumers in China.

Truth be told, they didn’t understand a thing about the Chinese or the markets of China, but they knew there were people there and they thought they could market their cotton to them.

CM: I recently learned how Confederate naval ships would attack Union whaling ships in the Pacific. Was there a process by the Confederacy of targeting non-slave trade goods during the civil war?

KW: It manifested more as a fear than what actually materialized. One of the first things Abraham Lincoln did at the outset of the war was to suspend gold shipments from California, because he was worried they would be seized by Confederate privateers. There was one quixotic Confederate campaign that was launched in California: a guy called Asbury Harpending (you can’t make these names up) recruited a bunch of California Confederates, armed a ship, and prepared to sail it out of the San Francisco harbor. His plan was to capture a whole bunch of gold ships, arm them, and turn them into a mini-Confederate armada in the Pacific.

He never got out of the port, but the fact is that the Confederacy was eyeing the gold shipments because they knew if they could disrupt or capture them, they could really take it to the Union war effort.

CM: You write, “Convinced that the markets of Asia and its six hundred million consumers promised a vast new frontier for their plantation economy. Slaveholders devised a set of initiatives to harness the Pacific trade. They sought nothing less than a global web of cotton commerce stretching from the docks of Liverpool in one direction to the trading houses of Canton in the other.”

Europe, at this point, was moving away from slavery. In the early nineteenth century, actually. Did nations have any reluctance to trade with the South because of its continuing practice of chattel slavery?

KW: They probably wish they did, but the fact of the matter is that the American cotton trade was far too lucrative for the major European powers to give up. They scolded slaveholders on the one hand while taking their cotton with the other. Southerners, in turn, looked at places like the Caribbean, saw that the British were importing tons of Asian contract laborers to work on plantations there, and they said, “A-ha, see? Free labor does not pay in these plantation economies! You need unfree labor of some sort”—whether that’s enslaved Africans or indentured Chinese workers or other Asian workers, it’s unfreedom that’s going to rule the world.

From a certain perspective, in the 1850s, it looked like they weren’t entirely wrong.

It wasn’t just Southern slaveholders who benefited from the expansion of US borders and the growth of the cotton trade. A lot of people were making money on this commerce. And a lot of Americans, North and South alike, supported imperial expansion.

CM: You write, “Slaveholders also waged a campaign to construct a transcontinental railroad through the deep South and into California that abolitionists ominously dubbed the ‘Great Slavery Road.’ A Pacific railway, white Southerners argued, would funnel their plantation goods across the continent and to the sea lanes beyond.”

The story we’re always told, though, is that the North believed in the technology of railroads while the South chose to continue focusing on rivers for trade—a story that reinforces a belief that the South made poor or even backwards decisions, thus losing the civil war. How is the South understood differently when we understand their more continental vision for slavery? What happens when slaveholders are seen as unsophisticated yokels instead of a scheming master class?

KW: We have this image of the typical Southern planter in the 1850s as a colonel Sanders-esque aristocrat reading musty copies of Walter Scott. But it’s just as likely that he was profoundly interested in modern technology and capitalist accounting methods, and thought really seriously about how one could marry technology and slavery. One of the ways you do that is by building railroads.

The South was industrializing at a really rapid clip in the 1850s. I think if the South had won independence it would have been the fourth-most industrially sophisticated nation in the world. It had more railroad track mileage than any European power. Southerners thought that if they could just build a railroad across the country, through slave country and into New Mexico and California, that they would control the main commercial artery in the United States. And that would have been the case.

We don’t usually think of slaveholders as railroad entrepreneurs, for a few reasons. One is that stereotype that I mentioned. Another is the fact that a transcontinental railroad never got built prior to the civil war. It took until after the war itself. This is something I describe as a monumental non-event. The railroad didn’t get built, so not many historians think much about the transcontinental railroad debates of the 1850s. They’re not very sexy. But they were really important. This was the major political wedge issue of the era, and it triggered a whole lot of other political issues that were related to it.

CM: You write, “The federal government, and more specifically the executive branch, was the primary mechanism through which Southerners extended their influence over the far west. From 1853 to 1861 pro-slavery Democrats controlled the executive. Presidents Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan, although natives of free states, appointed slaveholding partisans to key cabinet positions—a gesture to the Southern voters who secured their elections.”

Was it US policy leading up to the civil war to expand the South’s influence as well as the slave trade and the market for goods produced through slavery?

KW: To a large extent it was. It wasn’t just Southern slaveholders who benefited from the expansion of US borders and the growth of the cotton trade. A lot of people were making money on this commerce. And a lot of Americans, North and South alike, supported imperial expansion. So I don’t mean to suggest that every time the United States engages in an imperial enterprise in the 1850s that it’s Southerners and Southerners only who are calling the shots. But it’s one of the reasons their political agenda was so successful, at least for a time: because they were able to build support in places beyond the South.

CM: You write, “By uncovering the old South in unexpected places beyond the cotton fields and sugar plantations that exemplify the region, [you] bring together histories that are often divorced in the popular mind, with consequences for how we understand politics and race to this day.”

How and where do you see that impact revealing itself to this day?

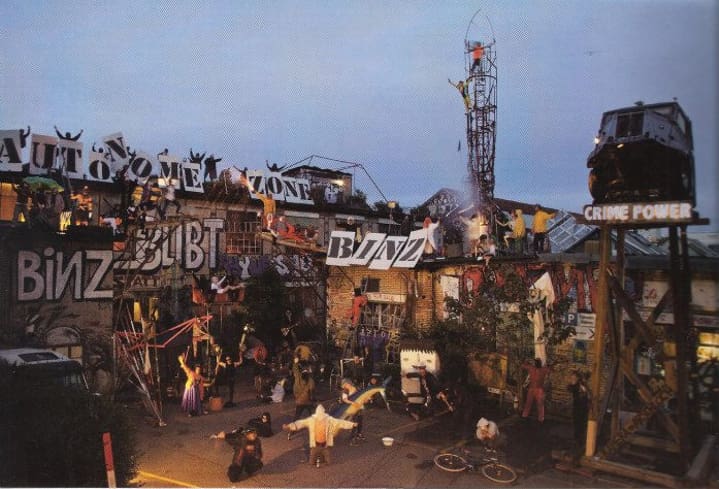

KW: It was maybe most prominent and recognizable in California until very recently. Most people seem to think California is a bastion of cultural pluralism and progressive policymaking, but California had more Confederate monument than any other free state. There were more than a dozen monuments and place names in California that honor the Confederacy. Most of them have been taken down or renamed—a lot of them in the wake of the murder of George Floyd. But of course it’s not only in monuments that the long influence of slavery can be seen.

It’s in the racial policies of the west. I guess also it’s in myths and stories that westerners like to tell. Like you said at the beginning of the show, it’s supposed to be this landscape of rugged individualists—but that’s just not tenable.

CM: You write, “In tribute to the antebellum railroad campaigning, several California monuments celebrate Jefferson Davis as the ‘Father of National Highways.’ Davis may have failed to construct a Great Slavery Road, but his ghost now graces a Great Rebel Highway.”

How is Davis the “father of national highways”? Are the Daughters of the Confederacy (the organization that was behind the early twentieth century program to have highways’ names changed to make a contiguous Jefferson Davis highway) giving a hat-tip to Davis and the Confederacy’s plan for a Great Slavery Road?

KW: I think they were. I’m glad you caught that, Chuck, because it’s really bizarre. No one in their right mind would actually consider Jefferson Davis the father of national highways. But the guy was an avid proponent of the Great Slavery Road during the 1850s, and he spearheaded several Pacific railroad surveys when he was the secretary of war. It’s true that Jefferson Davis was really interested in infrastructure, primarily as a way of expanding slavery across the continent, but “the father of highways” is a bit of a stretch.

More and more people are coming to recognize this history, and I think the John Wayne and Clint Eastwood myth of the west, slowly but surely, is eroding.

This is also a funny bit of trivia: Davis was the architect behind a bizarre American scheme to import camels into the southwest. He called them “ships of the desert.” He thought you could use camels instead of horses to put down Native American resistance in the southwest, beat back the Apaches and Comanches, and extend American sovereignty over this region—and then, through that means, slavery can leak across the continent. So he imported something like a hundred camels into Texas, and then eventually New Mexico and California, before the civil war.

Some of those camels and the descendants of those camels were spotted decades after, roaming the desert. The project never really went anywhere, but it’s another example of just how resourceful (I guess you could call it) some of these Southerners were in trying to put forward their plans for expansion into the west.

CM: You write, “The newest and largest Confederate monument in California, a nine-foot pillar in an Orange County cemetery, met a similar end to other monuments. Erected in 2004, the monument bore the names if numerous rebels, including some—like Stonewall Jackson—who had never set foot in California. A 100-foot crane lifted it from the cemetery grounds in August 2019, purging California of its most audacious Confederate tribute.”

2004? Who was behind that monument being erected in this century?

KW: Isn’t that wild? At the unveiling of this monument, all these Orange County dudes dressed in their Confederate gray took photos in front of the thing. It was like a big cook-out for them. It was a local Confederate memorial association that erected it. It didn’t really attract all that much attention in 2004. I think that’s one of the reasons you could erect so many Confederate monuments in California prior to Charlottesville: they didn’t generate that much attention. It’s only recently that people started writing about them and thinking really seriously about what these monuments meant.

CM: You point out how there were different ways the civil war ended for the South and for the west: “The plantation South had been shattered, but elements of the Continental South lived on. In the twenty-first century, California’s Confederate monuments and place names spoke to the enduring and often overlooked hold of the old South in the far west.”

So, postwar, was the way the power of white supremacy was challenged in the southeast any different to how it was being challenged in California? Did the federal government really focus on the South and give California and the west a pass?

KW: Yeah. That’s a good way of putting it. White supremacy could spread in more insidious ways in the far west because it wasn’t an issue of federal concern as were the former Confederates in the South during the Reconstruction era. I uncovered the emergence of the KKK in California in the late 1860s. It was basically a copycat organization. They saw the effect that Klansmen were having in the South, and they directed similar tactics—not against African-Americans, because there weren’t that many in California at the time, but against Chinese immigrants. The Klan in California got going as an anti-Chinese campaign. There were dozens of attacks on Chinese workers in the state during this time.

They sort of floated under the radar, because they weren’t as numerous and maybe they weren’t as threatening as the Klansmen in the South. They certainly were threatening to the communities that they attacked.

CM: You point out, “The west as it exists in the American imagination, and even in much historical literature, lies far beyond the shadow of slavery. The most enduring images of the nineteenth-century frontier feature white pioneers and rugged individualists leaving behind the political schisms that convulsed the eastern half of the country.”

Is the myth of the west a west that erases slavery of the Indigenous and those of African descent? Are Westerns an idealized United States that was untouched by the peculiar institution, the institution of slavery, which turns out not to be so peculiar at all?

KW: That’s part of the myth of the west. It’s a convenient myth. It’s a nice story. It’s a Clint Eastwood story. It’s a John Wayne story. That story doesn’t have a lot of room for slaveholders because it’s so fundamentally opposed to this foundational myth of the United States and the west. But more and more people are coming to recognize that slavery reached far beyond the American South. It’s not something I ever learned about when I was a kid growing up in California. I had great teachers, no disrespect to them, but we just never discussed the history of slavery in California because I don’t think it was on anybody’s radar. I had to go and do a PhD in Pennsylvania to learn about slavery in California.

But I think more and more people are coming to recognize this history, and I think the John Wayne and Clint Eastwood myth of the west, slowly but surely, is eroding.

CM: You write, “From Thomas Jefferson to Frederick Jackson Turner to popular portrayals today, the west has come to symbolize fresh starts and forward progress. These pioneer tropes obscure the ways in which slavery and its legacies radiated outward from the old plantation districts, instead placing the source of the nation’s racial problems squarely in the southeast.”

Was that the intent of Jefferson and Turner? Were those histories meant to be a kind of propaganda that censors slavery from US history?

KW: I’d say that someone like Jefferson was obviously eager to avoid the question of slavery whenever he could, because for him it was such a personal issue. But in his ideal America, slavery wasn’t going to reach west with these guys. He didn’t think through these questions as seriously as he should have. Then people like Frederick Jackson Turner, who characterized the American west as the nursery of American democracy—I don’t know if he simply didn’t know about the history of slavery in the west or if it wasn’t important enough to him and it didn’t jive with the thesis he was making.

CM: You write, “As Thomas Jefferson famously claimed, the west belonged to white yeomen whose economic independence and agrarian virtues would usher forth an empire of liberty. Roughly a century later, Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier thesis provided scholarly validation for the stories that Americans tell about the west. Purportedly free from the squabbles over slavery that convulsed the eastern half of the country, Turner’s frontier was the nursery of republicanism and virtuous self-sufficiency. Meanwhile, a pervasive pop culture industry, beginning with dime novels and then migrating to the silver screen, embellished these myths of a free and vigorous white frontier.”

So to what extent do you think white supremacy depends upon that foundation of a mythical history? And since this is accepted history in so many classrooms across the United States, to what degree can we change the history that white supremacy made up and depends upon?

KW: I’ll give an answer I think that Marx would like (at least the start of it): know your history. Learn history and the historical processes that give rise to the conditions we’re living in today. I think there is a silver lining here, Chuck. We’re living in a much better world now than we had in 1850s America. Whenever I get especially beaten down by the depressing topics that I study, it’s nice to step into the modern world—all the problems that we do have notwithstanding.

But if we look back we can see that progress has been made. We’re reaching desperately towards a better future. We’ve got a long way to go. But learning about the past, learning about the mistakes that we’ve made, and learning about some of the advances that we’ve made too, is a step in the right direction. Identifying white supremacy is part of the path to curing it.

CM: Kevin, thanks so much for being on our show.

KW: Thanks so much, Chuck.