AntiNote: this zine by anonymous authors in Minneapolis has been circulating locally since the recent municipal elections in which the mayor who presided over the police murder of George Floyd was re-elected and a special ballot measure to begin changing the structures that maintain and enrich the violent racist MPD was narrowly defeated by scared rich white people.

Here it is adapted for web reading; the text speaks for itself. PDFs of the real-life zine for reading and printing linked at top and bottom. Please download, copy, and distribute as you like.

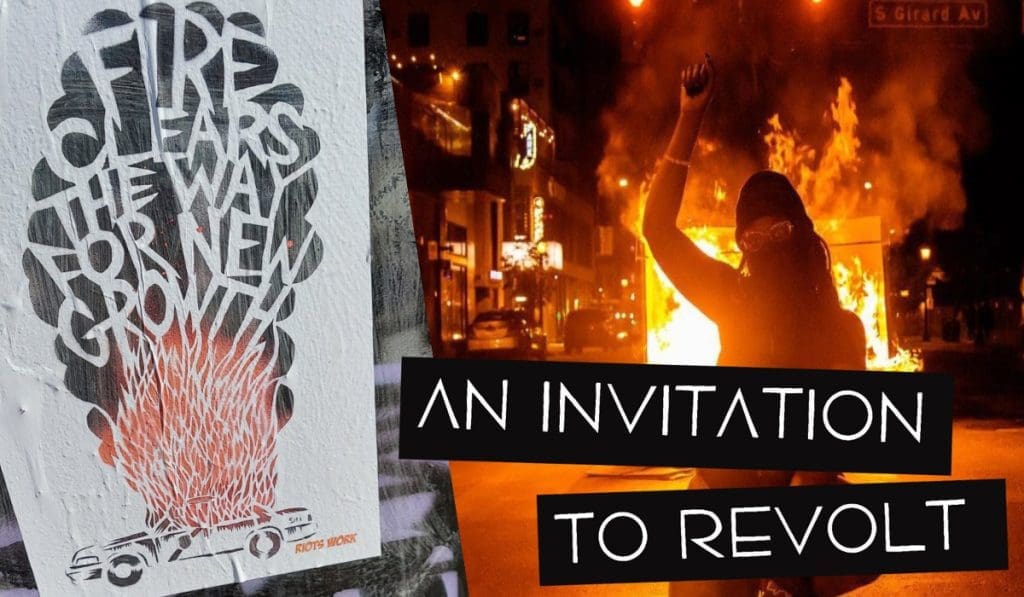

An Invitation to Revolt

Anonymous authors in so-called Minneapolis (Mni Sota Makoce)

November 2021 (PDF for reading | PDF for printing)

So, you’re an abolitionist in Minneapolis, and you just lost at the polls. Now what?

** Not from, or new to, Minneapolis? Unfamiliar with the history? See the appendix for a brief overview of what led to this moment in November 2021.

We’re abolitionists too, perhaps of a little different flavor or spice blend. And this is an invitation to come join us now that this historic election is, well, history.

Maybe you took a canvassing gig to make some extra money, or volunteered for the most-palatable candidate’s campaign or the so-called “public safety amendment”. You boosted #NoYesYes and #DontRankFrey and your fave candidate’s infographics on social media. Maybe you phonebanked, talked to your neighbors, handed out yard signs. Maybe you just came home from work, wished you had the energy to do more, and threw a few bucks at the people you thought could use it best.

Maybe you’ve felt a little exploited by politicians and nonprofits in the process, or wondered if what you spent the past few weeks (or months, or years) working towards was really the best use of your energy. Maybe now you’re feeling burned out, disillusioned, wary. Maybe you’re trying to put on a strong face – the fight continues, but… how?

If you see yourself in any of that – then, this invitation is for you.

Let us begin to find each other.

Explanatory note: To be clear, the following offering is specifically for visionaries and rebels who believe in fighting for worlds without police. (We would go a step further and say worlds without policing.) This text will not bother to argue why this is necessary as we consider it a given. If you’re reading but aren’t convinced about why a police- and policing-free present and future is necessary, we invite you to check out some of the many introductory resources on the subject instead, or some of the suggested readings listed at the back of the print zine and in the footnotes.

WHAT’S BEEN WON

First, congratulations on making some big gains over the past year. You (together with everyone else arguing for Yes on 2 and against the re-election of Jacob Frey and the other most odious backers of policing) have helped solidify “police reform” as a default moderate/conservative position in local politics – and arguably much further afield. The Uprising started this shift, but the ballot initiative forced so many to take an official position on it, whereas previously they could simply hang a Black Lives Matter sign in their window and call it a day. Instead of fighting to maintain particular policies or structures, they must instead now fight to defend the entire existing order of things, the very foundations of their castles.

As abolitionists, we know “police reform” is an impossibility; while certain tactical reforms that shrink the size and scope of policing and associated carceral systems can aid us on the road to abolition, reform as a strategy would only strengthen our enemy’s position.i Nonetheless, to have reform be the public position of everyone from Jacob Frey to the Operation Safety Now PAC, to Trumpist council candidate Victor Martinez, to the police department itself and even high-ranking Republican officials, is a huge shift from the “police can do no wrong” attitude prevalent only a few years ago.

Conservatives and liberals in opposition to City Question 2ii framed the amendment as an initiative meant to “abolish the police,” and corporate media posed the question as a referendum on whether to remove, replace, disband, dismantle, defund or abolish even though it clearly would not have done any of the above. The upside of that? By their own framing, 44% of the electorate voted in favor of this! Furthermore, sixty thousand voters in the mayoral race ranked Sheila Nezhad, an avowed police abolitionist who was agitating to end policing before it was cool, and who as a street medic was out in front of the third precinct treating chemical weapons exposure and rubber bullet wounds for frontline fighters during the uprising.

And of course there’s the untold hours spent having conversations with other Minneapolis residents about the issue, moving prior enemies into neutral players, and neutral neighbors into potential allies. That work of one-to-one conversations is proven to pay off down the road.

Unfortunately, so much of the discourse around City Question 2 became a battle of narrative rather than substance. The emotion-driven shouts of “Where’s the plan?!” versus “It’s literally right here!!” obscured the possibilities that the flames rising from the third precinct had clearly illuminated a year before. Branding the initiative as “Public Safety” rather than “Liberation” also closed doors that had been smashed open during the riots. That limited our imaginations only to determining how to best stay “safe,” rather than how to free ourselves, which is the only way to ensure lasting safety.

Now that the task of persuading the electorate is over, we can say fuck the optics and slogans and admit two crucial truths: that the initiative did indeed have its roots in movements toward police abolition, and also became so watered down both in its bark and its bite as to make many abolitionists wonder whether the new “Public Safety Department” it proposed to create would actually do more harm than good. True, it would have rid the city charter of a minimum policing requirement. But Yes 4 Minneapolis spokespeople went out of their way to assure the liberal and centrist masses of Minneapolis’ elderly white electorate that their goal was not to get rid of police, but rather simply to reallocate resources so that police could do their jobs “better” without having to also serve as impromptu mental health workers or outreach specialists.

For those of us who would rather police not be enabled to do their jobs better but who want them to get progressively worse at it and then cease to exist within our lifetime, along with all other agents of policing, we’ve just seen the limits of elections…some of us for the first or second time up close, some of us for the umpteenth.

The alternative is a deeper abolition than the voting booth could even pretend to offer: of the cops and politicians inside our heads, which in turn leads us to the abolition of policing, prisons, the state and all forms of authoritarian social control.

In other words: the practice of uncontrollability, and of becoming ungovernable.

“Should we answer it? Let’s answer it,” I said to my partner, after hearing another knock on the door. It’s election season, and that means canvassing time, and our little house just seems so damn approachable. The last ones were with “All of Minneapolis,” the right-wing PAC that just hired a bunch of kids off craigslist. They didn’t have their heart in it, so we showed them how to fake their canvass data.

“Hi, my name’s Sheila, and I’m running for Mayor of Minneapolis…” Ooh, an actual candidate this time! After exchanging small talk, my partner decided to cut right to the chase. “Look, we’re abolitionists too, so we already know you’re better than everyone else running. But why are you only talking about abolishing the police? I want to talk about abolishing YOU!”

“Back during the uprising there were so many moments of empowerment. Walking through the Target/Cub parking lot while everybody was just going in and out of stores taking what they needed, giving snacks and med supplies to people on the frontlines, treating themselves, sending cartons to mutual aid pantries… that was heavenly. Stopping for a selfie in front of the tipped over and burned down sky cam! Burning barricades in the street to keep each other safe, the whole city a canvas – despite all the pain and struggle it was also a glimpse into another world I never thought was possible. That week changed me like nothing before or since.”

“We’ve had some tastes of that since then, like at times in Brooklyn Center and Uptown, but it hasn’t been the same – not enough regular folks joining in spontaneously, and the state has gotten a lot smarter since then. How do we bring that feeling back?”

[Additional inspiring first person testimonials of revolt from the past 18 months in the Twin Cities – from kettling cops to expropriating food to facing off versus fascists – are scattered throughout the printed zine version of this essay, and also appended at the bottom of this page.]

ALWAYS FIGHT

The real stories and reflections spread throughout this zine give some examples of what ungovernability may look like for different people. However, through these examples, we do not wish to privilege or uplift particular forms of struggle over others, so long as all reject a politics of control and of being controlled.

Some may ask us: “So, you just want to fight the cops and that’s it?”

Of course not – we also want to fight politicians, school administrators, bosses, concentration camp paper pushers, social service gate keepers, and authority figures of all sorts who uphold systems of punishment and policing.

To which those same critics might respond, “So… you just want to fight and that’s it?”

Yes, now we’re getting to the heart of it!

The trick is that the fight must be present in all our activities, whether steamrolling a cop to de-arrest a comrade, learning to treat wounds so we don’t need the ambulance, or planning to blow up a new jail under construction. After all, we didn’t start the fire of the post-1492 social war–but it continues to burn in every moment of our lives so long as we live under police, capital and the state. Thus, our resistance activities must necessarily include conflict.

Fighting fascists wherever they appear, the burning of police stations, the prison riots, the middle of the night acts of destruction and creation—are all crucially important. So too is the fight we bring to the creation of community gardens, mutual aid pantries, encampment support, building communication infrastructures, political education, and much more. Whether at a street blockade or in front of one’s computer; a black bloc or a seed-saving class—if conflict is not present, our actions do little towards the future we want to see. That future will be built with guns, food, incendiaries, shelter, rage, love, and so much more…but always, always with conflict as a key ingredient.

In the days after the height of the George Floyd uprising—and especially after that infamous Powderhorn Park event at which “fearing for their lives, city politicians actually resolved to disband the Minneapolis police—a decision easily reversed once they regained control of the streets”iii—the focus of rebellion became less on militant street action and more on mutual aid. Some of that mutual aid work can be accurately described as militant, grounded in struggle, and heightening conflict with the state and capitalism—most notably the takeover of the Sheraton Hotel into a sanctuary for the unhoused,iv the subsequent struggle to establish encampments in parks, and thereafter some instances of militant camp defense by unhoused residents and supporters. But much of it blurred the realm of solidarity work and functioned more as de facto service work, devoid of political analysis or conflict.

Such work can and should build conflict into the fabric of its activities. As one critique of common characteristics in modern self-proclaimed mutual aid projects explains,

“Honest service work is not always antithetical to a broader struggle which is primarily propelled by target-and-demand driven projects. They can be a very good supplement, to the point where if you are in a growing group dedicated to class struggle that is really making bigger and bigger moves, devoting a bit of extra labor in this direction is a good idea. However, it raises the question of an overall strategy, and where we really want to put our faith. We need to harvest new relations and forms of care, but outside the context of conflict, we lack the thrust which gives these new forms their class character.”v

This critique cites historical examples of honest service work (projects that no doubt might be called “mutual aid” today) that integrated conflict and class struggle into their approach. The Black Panthers’ survival programs existed alongside armed community defense and explicitly revolutionary organizing. Literacy programs have been used not just to teach people to read, but “to actually further be able to reach people and deepen their relationships,” building political education and the comradeship necessary for confrontational struggle.

The past two years of struggle in Minneapolis have been filled with examples of mutual aid/service work/community building that centered conflict. George Floyd Square is perhaps the most visible example of this (although the amount that the revolutionary, militant spirit of its formation has been co-opted and re-formed greatly complicates any full analysis). At the heart of the GFS project, aside from the maintenance of a sacred site and its initial function as a base of organizing during the Uprising, is an occupation of territory for a wide array of activities that serve community—to the dismay, irritation, and even fury of the police and allied political forces. All these activities could, theoretically, take place at permitted, non-confrontational locations, in quiet corners of the urban landscape, but instead each act that takes place in the square, no matter how seemingly mundane, speaks “these are our streets and our city, cops and rulers be damned.”

Similarly, the creation of community space at the site of the assassination of Winston Smith and murder of Deona Marie Knajdek Erickson in Uptown positioned conflict at the fore not just among the looting, fires, and black blocs that manifested, but also in the vegetable gardens, discussion circles, and campfires. Graffiti artists engaged in pitched battles each night with vigilante whitewashers who during the day tried to erase the names of our fallen accomplices and our dreams of liberation. Community garden projects in contested spaces elsewhere had similar effects, as did actions by unhoused people who moved into previously off-limits territories.

For examples of conflict not rooted in the occupation of physical space, we can look to the autonomous groups of neighbors who cooked hot meals for encampments, mostly funding their efforts through small (if any) monetary donations and with much food sourced via dumpstering and expropriation. With no strings attached (as in a nonprofit structure or when accepting large monetary donations), these loose groups were able to skirt city regulations about serving meals that had frequently been used to crack down on such activity—today those regulations are rarely enforced, but when the city attempts to do so, mutual aid workers will disobey and continue to get food to those who need it anyway.

In contrast, efforts to ameliorate conditions for unhoused residents by a nonprofit that fundraised for hotel rooms became mired by gatekeeping, to only short-term benefits for the people they purported to serve. Actions in response to the MPD murder of Dolal Idd were mostly organized by professional/celebrity activists and nonprofits and followed a predictable pattern of marching around the neighborhood with not much more than holding signs and chanting. Accordingly, the rebellious spirit that erupted in the aftermath of the murders of George Floyd, Daunte Wright, and Winston Smith never materialized.

So, yes—the answer to “So all you want to do is fight?” is a resounding “Hell yeah.” No matter what form it takes or what part of the battlefield we choose, we can either fight, or forfeit. Let’s fucking go!

SUN POWER

Go where? Before further inspecting what ungovernability might look like for you in practice, should you choose to take up the mandate, we must first (both individually and in our horizontal groups) analyze the power relations of the current terrain. Movement elder and police/prison abolitionist Ricardo Levins Morales conceives of power by speaking of “moon spaces” and “sun spaces.” In an essay analyzing a city council race in 2013, he explained the concept by writing:

“I don’t ignore electoral contests exactly but they don’t dominate my attention, either. You see city councils, legislatures, courtrooms, and negotiating tables are what I call “moon spaces.” The moon gives you light to work by but it doesn’t actually generate any. It’s all solar power beaming in from the streets, workplaces, school yards and prison yards. […] I work in those “sun spaces.” Getting someone into office can indicate a shift in power but doesn’t cause it.”vi

We must spend more time creating power in the sun spaces. Politicians and electoral and legislative campaigners, as well as professional activists who use the same old tactics time after time after time yet seem to expect different results (or do they?) know this because it’s where they go to make it seem as if they create solar power, rather than mere reflections of moonlight. Consider those four incubators of people power Levins Morales lists:

The workplaces: Politicians are quick to tout their labor endorsements, even though those endorsements are usually made by crusty executive committees and not the rank-and-file. Even when the endorsements come from such conservative unions as the building trades or firefighters, politicians try to use them to pad their alleged credentials. Even relatively left-wing sections of the labor movement have enabled this—nary a union activist was calling for the expulsion of police unions from the labor movement umbrella, before the George Floyd Uprising.

While the politicians seek to portray themselves as workers, the capitalists—which includes NGO executives and management—know that the workplace is a battlefield. Anyone who’s been forced to watch a union-busting video, stood under a security camera for a ten-hour shift, or been sternly told not to discuss their pay with coworkers, can attest to the utter terror of bosses well aware of the prospects of worker revolt.

The school yards: Like the workplaces, these are a key battleground for those who seek to maintain state and police control. Contemporary battles (often lopsided in favor of the far right) for control of school boards and curricula are proof of the school yards’ power, as is the vast extent of digital surveillance of students as recently exposed by Minneapolis South high schoolers.

Like with union endorsements, hopeful lefty politicians see the power of aligning with youth struggles, too. When Northeast Middle School students walked out shortly before the election against a teacher’s racist remarks and the failure of administration to respond, two mayoral candidates were quick to roll up in their campaign-mobiles decked with signs and slogans to accompany the students on a march.

The prison yards: Here, and in the detention centers, immigrant concentration camps, juvenile jails, and myriad carceral “community programs,” like a chess player guarding her king, the state telegraphs what it fears the most: widespread revolt by those who, if enough chains were broken, could seismically shift the balance of power. A small spat of looting in a commercial district may prompt unhinged national politicians to crow about “anarchist jurisdictions,” but regular occurrences like prison riots, killings of guards, hunger strikes and various other forms of rebellion often are not known to those of us on the outside until disseminated via illicit social media posts, whispered phone calls or long-delayed letters.

The politicians, nonprofits, and celebrity activists rarely bother to try to co-opt the solar power coming from the prison yards…although we do increasingly see today’s slaveholders and concentration camp administrators attempting to rebrand themselves with such dystopian language as “housing providers” or “community justice service providers”—further evidence of the threat we pose when we aim to tear down their walls.

…And the streets: The territory prowled not just by the blue-uniformed gangs representing law and order, but also by the established activists and their organizations stuck in the same script of token opposition.

An illustrative example: At an October 2021 march to City Attorney Jim Rowader’s house near the northeast corner of Bde Maka Ska, demanding he drop charges against the 646 protesters arrested on I-94 the day after the 2020 election, marchers easily could have chosen to disrupt the heart of Uptown and visit the much-contested nearby site of the assassination of Winston Smith. Instead they chose a residential route, shying away from potential confrontation with authorities who in recent months have been made to shake in their boots at any mobilization in the commercial center of Uptown.

Notably, even when leading chants of “Fuck 12” and “All Cops Are Bastards,” the organizers passed around petitions for “community control of the police,”vii as if, well, all cops are NOT bastards who won’t submit to such a thing. Many of those organizers, in fact, had publicly announced their outright opposition to City Question 2. Ironically, the “Department of Public Safety” proposed by the ballot initiative mimics the state level department which includes the State Patrol, who conducted the mass arrest and kettle on I-94. This wasn’t the reason for their opposition, however, which instead was framed largely in terms of practicality, with more than a hint of unresolved beef about certain abolitionists stealing their thunder as some of the city’s celebrity activists.

Examining all these strategies used by different actors of social control—politicians, capitalists, nonprofits, activists—when they attempt to challenge the sites of solar people power helps us see at which avenues of attack they may be most vulnerable.

Mapping out this battlefield reveals that arguing for mere abolition is no longer sufficient.

ABOLITION AS THE COMPROMISE

A good negotiator knows that you always ask for more than you’re going to get. A union’s first contract proposal inevitably contains far more benefits for workers than the contract that ultimately will be ratified. From our enemies’ point of view, a “good” prosecutor always piles on more criminal charges than they know will actually stick, or than a jury is likely to convict on. Some riot here, conspiracy there, assault, unlawful assembly, public nuisance…by shooting for total destruction of a defendant’s life, they know they’re more likely to at least get a small jail term, even with the best criminal defense.

In 2010, two different campaigns fought to increase the minimum wage in Minnesota—a “respectable” campaign asked for $9.50, the “pie in the sky” campaign asked for $15, and it was then deemed an unrealistic proposal. In 2021, the MN minimum wage is only $8.21 ($12.50 in Minneapolis). Cost of living has soared such that low wage workers are effectively getting less and less pay each year. Only now are people daring to ask for $25, $35, or more as a livable minimum wage (The critical goal would be the elimination of bullshit jobs and the abolition of work itself).

For decades, demanding abolition (referring to police, policing, and prisons now) was smart because it was not even within the Overton windowviii of respectability. That has changed, and yet the demand has not grown as the terrain has shifted. Currently, defenders of police can sleep comfortably without worrying too much about abolition because, when ignoring it, laughing it off, or attacking it head-on fails, the demands of police abolitionists can easily be re-defined, re-formed, and re-packaged into things our conception of abolition is not: in short, the Police 2.0 currently previewed by “community policing” initiatives, recuperative processes that shift policing responsibilities to other structures such as Black-operated nonprofit patrols,ix and “violence prevention” initiatives that only address interpersonal and not systemic violence nor the violence of the police itself.x

Police abolition is no longer a pie-in-the-sky goal. As such, it should be the compromise position, one that the reformists will eventually concede to because the alternative—unceasing attacks on police, policing, prisons, and power itself—becomes too great for the system to bear.

A graffiti slogan has been increasingly noticeable throughout town these past few months, when it evades the foam rollers of the whitewashers and the public works department: “Save Lives, Kill Cops” or “Kill Cops, Save Lives.” Whether you view this slogan as speaking to the physical homicide of police officers, a metaphoric call for the complete annihilation of structures of policing, or both, is irrelevant. Its call is for two things that will never be achieved in, nor co-opted by, the moon spaces of government: the complete death of the forces by which government upholds itself, and the prioritization of human life over the structures of carcerality and capitalism.

“Save Lives, Kill Cops” is, of course, a little too “spicy” for a candidate or nonprofit or professional activist to sign on to…and that’s exactly the point! In positioning police abolition right where it should be as the compromise position, our aspirations can be weighed by exactly that test. Annihilate policing and the founding logic of punishment both. Burn every prison and free every prisoner—even the innocent ones. Tear down every state house until “politician” is a forgotten concept.

Prosecute the policexi? Worthless. Abolish the police? We’ll settle for it. Execute the police, as some long-lasting graffiti at the site of Winston Smith’s assassination declared? Now we’re talking.

End mass incarceration? Not enough. Abolish prisons? We’ll settle for it. Every city every town, burn the prisons to the ground—now we’re talking.

Harm reduction by voting? If you insist, but it’s still just keeping the structures that manage our desires alive in a vegetative state, before we inevitably must come to grips with reality and pull the plug. People over profits, power from below? We’ll settle for it. Death to capitalism, amerikkka and imperialism everywhere? Hell yeah—ain’t nobody getting elected on that platform!

It is useful to look at the “abolition” of slavery (in quotes here to emphasize that abolition, like revolution, is not an event but a process—despite emancipation, no such total abolition of slavery in fact occurred) as a history lesson when considering how high we must aim.

Modern police abolitionists frequently point to slave patrols as one origin of modern systems of policing, and this aspect is well understood. But we would do well to study also both the resistance (the general strike of the slaves, and especially the transition from a mode of struggle centered on persuasion to one built around force) as well as the re-formation of white supremacy (wage labor, sharecropping, imprisonment, lynchings, Jim Crow) in ways similar to how we have been seeing the accelerated re-formation of policing.

The brutal human cost of that time period tempts one to delve into the the necessary violence implied by the “Save Lives, Kill Cops” slogan, and how it may compare to the brutal costs of our current time period. We will not do so here, though, except to note that “nonviolence has lost the debate.”xii

Police abolition should be our compromise, fallback position. Frankly, it’s a good deal for the ruling class colonizers, compared to what we could achieve if we really put the pedal to the metal: complete annihilation of policing, prisons, the state and all rulers, and freedom for ourselves and all those we love.

LET’S FIND EACH OTHER

“Of all the modern delusions, the ballot has certainly been the greatest… The principle of rulership is in itself wrong: no one has any right to rule another.”

—Lucy Parsons

Abolition, revolution, is the daily pushing over the table we’ve been forced to sit at, and standing up to continue the task of creating another world. This daily act is part of a process of rage and negation, but also of joy and love. Consider this account of the riots in May 2020:

“The uprising was a meeting of strangers, and yet everyone was invited to take part in the festival of revolutionary violence. It didn’t matter what your specific vision of the future was. Your passport through this world was your actions, your willingness to fight, burn, and take risks in the moment, and this unique passport allowed all to become human…This is why the rioters chanted “We All N***** Now!” as multi-racial crowds looted and fought the police.”xiii

It’s not just the police we must fight, of course. Remember “the whole damn system is guilty as hell”? It’s the entire principle of rulership, as Lucy Parsons put it. Although many Minneapolis police abolitionists are also committed prison abolitionists, and struggle against all forms of rulership from the state to schooling to enforced monogamy, too many have so far had their field of vision limited as a result of the specific conditions created in Minneapolis before, during, and after the George Floyd uprising. Even though it was specifically police abolition that surged into the spotlight, police and even policing is but one face of the totality that must be annihilated.

As we set upon the task ahead of us—perhaps discarding the organizations and formations that grew strangely contorted and toxic from the past year’s electoral soil—the ways we can address that totality, the ways we push the table over each day, thankfully also point to how we might find like-minded comrades to join us in the revolutionary festival.

Are you communicating with abolitionist and political prisoners and prisoners of war, and supporting the prison strikes already planned for late summer 2022? Expropriating from work, perhaps finding in the process comrades doing the same? Taking cues from the youth struggling against the carcerality of educational institutions? Writing on walls, stepping off the sidewalk, embodying unmitigated hostility toward our enemies and the “no peace” in that one tired, worn-out slogan?

And crucially, in the process, noting who among us is doing the same, and finding each other?

We’ll be looking for you.

APPENDIX: BACKGROUND & BALLOT LANGUAGE

During the May 2020 George Floyd Uprising in Minneapolis, a horizontally organized, multiracial crowd of rebels burned and destroyed the Minneapolis Police Department’s third precinct and made the entire city, for a time, ungovernable. Thanks to their militant actions of rage and love, and the years-long efforts prior by abolitionist organizers and cultural workers to tend the soil and plant seeds, police abolition suddenly became a topic of mainstream global conversation for the first time.

After the embers cooled and curfews succeeded at quelling the riots, with anti-police sentiment at an all-time high in the city, nine city council members appeared at a now infamous event at Powderhorn Park, vowing to “defund” the MPD. [In this author’s experience, in those early days after the uprising, many police abolitionists used the words “abolish” and “defund” interchangeably (i.e., advocating for an eventual 100% defunding), where as at the time of this writing “defund” is more commonly understood to represent a reformist, “still police, just with less money” position.]

Predictably, all the council members quickly backtracked their position. With this about-face, activists seeking change via city government turned their eyes to a ballot initiative, as the city charter contained a requirement for a minimum number of police officers (notably, since the uprising, even this “requirement” has not been met due to large-scale attrition within the MPD). Their first attempt to get an initiative on the ballot in late 2020 was stonewalled by the city charter commission, a judicially appointed body most representative of Minneapolis’ wealthiest, whitest neighborhoods. Activists then successfully gathered 20,000 signatures to force a 2021 ballot initiative, which was still repeatedly stonewalled by court challenges, procedural wrangling, and revisions to the ballot language.

In their analysis “How (Not) to Abolish The Police: A Guide From the City of Minneapolis,” Crimethinc wrote in the week after the election:

“After a year and a half of obstacles, media fear-mongering, and vigorous PR campaigns from police departments around the country, a proposal to replace the Minneapolis Police Department with other agencies was put before the public in a referendum on November 2, 2021. At any time before May 26, 2020, if almost 44% percent of the voting population of any metropolitan area in the United States had voted to abolish the police, this would have been reported as a significant blow to the legitimacy of the institution of policing; Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860 with a mere 39% of the vote, and he was not even running on an abolitionist platform. This past week, however, centrists and conservatives claimed the defeat of the proposal in Minneapolis as a victory.“

This is the language that actually appeared on the Minneapolis 2021 ballot:

“Department of Public Safety: Shall the Minneapolis City Charter be amended to remove the Police Department and replace it with a Department of Public Safety that employs a comprehensive public health approach to the delivery of functions by the Department of Public Safety, with those specific functions to be determined by the Mayor and City Council by ordinance; which will not be subject to exclusive mayoral power over its establishment, maintenance, and command; and which could include licensed peace officers (police officers), if necessary, to fulfill its responsibilities for public safety, with the general nature of the amendments being briefly indicated in the explanatory note below, which is made a part of this ballot?“

The following “Explanatory Note” also appeared on the ballot:

“This amendment would create a Department of Public Safety combining public safety functions through a comprehensive public health approach to be determined by the Mayor and Council. The department would be led by a Commissioner nominated by the Mayor and appointed by the Council. The Police Department, and its chief, would be removed from the City Charter. The Public Safety Department could include police officers, but the minimum funding requirement would be eliminated.“

TESTIMONIALS TO REVOLT

Like every New Years Eve, people gather to make noise loud enough to be heard inside the cells at the downtown jails, to let those inside know they’re not forgotten. At the tail end of the year of the biggest uprising the city has seen in decades, the crowd is ready to fuck around. Dressed in black winter gear and masks to obscure identities, militants set off deafening fireworks and colorful smoke bombs, pound on drums and noisemakers, and cover the walls of the jail and nearby buildings with anti-cop graffiti, perhaps lingering too long before getting mobile again.

After moving on, police soon move in to trap the crowd—but a parking lot provides an escape route, as some comrades lift up chain link blocking the way so others can duck under it to escape. The group re-forms again headed another direction, but a poorly chosen next escape route forces the group to hurriedly turn around, straight into a police kettle. As officers announce the entire group is under arrest, the crowd screams and charges. One person throws a metal tea kettle at an officer, hitting the cop squarely in the chest – kettle this, pig! – giving themselves and others an opportunity to breach the line and escape. Others dash past slowfooted cops and into the nearby woods.

Many, however, are kidnapped by the state, forced face down into the snow before being hauled on buses to jail. Some huddled back-to-back while ziptied, holding hands to keep feeling in each other’s fingers. Comrades quickly organize jail and legal support, practices well honed after the previous year, maintaining vigil until all are at liberty again. The county attorney trumpets their haul to the media, noting the (legally carried) guns among some of those arrested and the strong organization of the group, inadvertently praising their dedication to keeping each other safe – “a dedicated EMT,” two-way radios, ample personal protective equipment and handwarmers. Five people are charged with felony riot, and others with a slew of lesser charges. As the months roll by, the vast majority of the charges are dismissed due to lack of evidence.

After a particularly tough action, some friends and I walked to a nearby park to recharge and recover. Turns out we weren’t the only ones with that idea. Total strangers passed around free snacks and free beers—no money exchanged at all. That sense of community, mostly with folks I’d never met, was amazing. A lil light into the better world we all know is possible.

Late night on the barricades at George Floyd Square over the winter…it felt like we were almost dying of cold, and the fires took so damn long to build at first, but we took care of each other. Our overnight crew got to know each other so well, and finding a new comrade to snuggle with helped keep me warm too.

In the wake of an uprising fed and nurtured by goods looted from the Target, Cub Foods, and Aldi across from the burned out husk of the third precinct, workers scheme new ways to loot back from their thieving employers. One person lands a job at a “Hell Foods” grocery store, biking each day from a beautiful Lake Street on which community gardens have replaced smashed and burned corporate shops, into a desolate wealthy neighborhood where the well-to-do buy their overpriced groceries in between browsing Nextdoor and watching MSNBC.

After a short period of scoping out the security cameras and learning which of their coworkers can be trusted, they begin moving carton upon crate upon pallet of food out the back door. Comrades receive instructions with a specific time to come pick up the haul, and how large of a vehicle is required. One load goes to a house cooking hot meals for the unhoused three days a week. Another, to the spontaneous gathering of those gathering in love and rage at yet another police murder. More, to feed an abolition study group meeting once a week in a park. If the manager is away, another station wagon’s worth can be sent to the people guarding the barricades at George Floyd Square through the cold winter nights.

Not a can nor a single fresh vegetable goes to the nonprofits that gatekeep access to their resources depending on who “deserves” it, who follows the rules, which of the unhoused are willing to submit to a religious spiel, charitable photo-op, or a night of family separation at a shelter. Hell Foods already takes care of those groups and gets a tax write off for it, after all.

Eventually, our conniving expropriator comes under suspicion by upper management. They’ve carefully planned for this moment. A new scheme is put into action, and within weeks, a different Hell Foods store’s security cameras are being scoped and coworkers appraised…

A group of unhoused neighbors is shuffled from park to vacant lot to superfund site, everywhere getting the run around by city officials. They finally are left alone by the city, cops and nonprofit-sheltermongers long enough to build structures to withstand the winter, while mutual aid workers raise funds for hotel stays on the coldest polar vortex days. With spring finally within sight, eviction notices are posted yet again. Nobody’s obeying this time. Unhoused residents join forces with housed neighborhood accomplices, and in the hours before sunrise, fifty people clad in all black gather. At dawn, several squad cars pull up and begin to tape off the area, as public works bulldozers wait nearby. The tape is pulled down, and dumpsters and other blockade materials rolled into the street. The police line is rushed and pushed back. Some people throw hands, others snowballs, and others their best insults. Defenders perform de-arrests that take officers off their feet. Despite kidnappings and assaults by the cops, the crowd holds the line and the outnumbered and overwhelmed police back down from the eviction attempt.

On television the police chief decries the attack on their officers, but the bulldozers stay away. The next day, a neighboring business calls 911 on a journalist, claiming their camera was a gun. Over the police radio, camp defenders hear the dispatcher report the call but instruct officers to stay away from the encampment “due to the prior day’s events,” and a cheer goes up. Defenders and residents build up barricades made of mini-murals, cache bricks and tires, and organize copwatch shifts for the coming months in case the cops come back. The cops don’t.

eight months later, the encampment still stands while countless others around the city have been destroyed and their residents displaced time and time again. In contemplating the eviction of a different camp, county officials reference the attack on MPD as a reason they are reluctant to carry out yet another bulldozing. Meanwhile, at a trial for assault on a police officer stemming from a separate eviction defense the previous fall, police admit on the stand that the community defense forced them to delay planned evictions several times. The defender on trial claims self defense against the MPD and the jury agrees, finding them not guilty.

Going out to confront the Proud Boys and Nazis in Saint Paul was something I’m really proud of having done in the past year.

It was the first time I’d been part of a shield wall, and I was nervous as all hell until I felt a comrade’s hand on my back. I didn’t know who it was, and there were no words – just steady reassurance – and I knew I was in the right place at the right time. Thankfully now we know how to make shields that aren’t quite so heavy though…

Afterwards, a few of us would always get together at someone’s place to smoke and eat pizza. We became best friends because no matter how tired we were, it was our after-action ritual.

When Daunte Wright was murdered, I was with a friend, we heard something had happened, someone was possibly killed by the police out in Brooklyn Center. We decided to go there together, and notified others what may have transpired as we tried to gather info. We came upon a police line, a growing crowd, an increasingly angry crowd. Peace police attempted to dampen the energy but to no avail, the police line was pushed back, eventually folks hopped up on police cars, smashing their windows with landscaping blocks. A man was shot in the head by a policeman’s rubber bullet and fell to the ground. The crowd quickly got him to safety from police and towards medical care.

The crowd began to murmur of what next, a vigil began, a speaking circle, music, and then the collective energy seemed to be moving towards the police department. Some drove there, and others began to march, knowing with the crowd split there would be issues with police. We hopped in our car, everyone shouting to each other to create the impromptu route and marshals. When we arrived at the police department, there were no fences as there are today, but hundreds of police had come to meet the crowds. The battle of BC had begun. Talk of looting was in the air, and there were no peace police to be found. The crowd militantly confronted the police and seemingly all of Brooklyn Center came out of their homes to stand in the streets. Megaphones and celebrity activists are no match for collective action, militancy, and true working class solidarity.

Anti-copyright: steal, reproduce, and modify at will.

Want to get in touch? Find us on the barricades.

Notes

i Much has been written about the distinction between abolitionist and non-abolitionist reforms. For those unfamiliar with the concept, this passage from IN THE BELLY: An Abolitionist Journal sums it up: “A lot of abolition can look like what reformers do. But the difference is that reformers think that we can fix these problems and have a fair, non-racist criminal justice system. We say that’s impossible – the whole thing has to be torn up, root and stem. So when we push for reforms, we push for reforms that weaken the system rather than strengthen and legitimize it. Fellow abolitionist and comrade Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls these “non-reformist reforms.” For example, building new jails to deal with overcrowding is a reformist reform – it ensures another century of jailing people. A non-reformist reform would be something like decarcerating and shrinking jail populations by funding communities and decriminalizing sex work, drugs, and homelessness. It won’t get us full abolition this year, but it pushes us that much closer.”

ii The text of the ballot initiative is printed in the appendix.

iv Even this – as much as the action was instigated by taking a needed resource by force, rather than asking for permission – was to a large degree co-opted by a nonprofit managerial class of activists, who insisted on using raised funds to pay the hotel owner, rather than to wrestle complete control away from him. Although many factors played a role in the collapse of the hotel takeover, a critical one was when, over a week after the occupation began, the owner, still able to access hotel computer systems, was able to remotely disable all room keys. A better approach than negotiating with the owner for so long would’ve been to further raise the ungovernability inherent in the act of moving unhoused neighbors into the hotel without asking, and cut the owner out of the picture entirely by any means needed.

v Gus Breslauer, “Mutual Aid: A Factor of Liberalism,” Regeneration Magazine, 27 Nov. 2020 https://regenerationmag.org/mutual-aid-a-factor-of-liberalism/

vi “Unity and Division in the Ninth Ward,” 4 Nov. 2013. Retrieved from https://rlmartstudio.wordpress.com/2013/11/04/unity-and-division-in-the-ninth-ward/. Notably, the candidate who won the city council race analyzed by Levins Morales in this essay, Alondra Cano, became perhaps one of the best local case studies of a lauded “progressive,” working class, representative-of-the-neighborhood, accomplished community organizer turning an about face after a few years of rule and becoming a functionary of police and corporate power.

vii See “The Fantasy of Community Control of the Police,” by Woods Ervin et al, at The Forge: Organizing Strategy and Practice, https://forgeorganizing.org/article/fantasy-community-control-police

viii The Overton window refers to the range of policies or discourse deemed acceptable by the mainstream population at a given time.

ix See “Field Guide to Twin Cities Collaborators,” Whittier Copwatch, 5 June 2021: https://antidotezine.com/2021/06/06/tc-collaborators/

x Here in Minneapolis, Sheila Nezhad, before running for mayor, agitated with Reclaim The Block for the creation of the Office of Violence Prevention which essentially served the purpose stated here. Publically, she touted OVP as a top achievement, critical to framing herself as the “Public Safety Candidate.” In quieter conversations, she admitted that the design and function of OVP was largely a mistake. While attempting to balance using her work towards OVP to boost her campaign, while also acknowledging the grassroots criticisms of it, she unintentionally showed the limits of an abolitionist framework that only addresses police and not the entire concept of policing and social control. That flavor of abolition, of course, would disqualify all but the most committed hypocrite from pursuing elected office.

xi See “Copaganda: Police Trials as a State and Media Kettling Tool” https://www.mpd150.com/copaganda-police-trials-as-a-state-and-media-kettling-tool/

xii “The Failure of Nonviolence,” Peter Gelderloos

All images via zine authors