AntiNote: This post is a return to one of our original habits and practices at the zine: boosting the personal and often tragic voices and profiles of people on the move seeking freedom and dignity, struggling for life against the forces of death. Youssef’s journey to the next world happened three years ago, but his story and that of those like him keep being repeated.

This tribute and reflection was written by an acquaintance of his in Bosnia who has given us their kind permission to share their words. There are many other thoughtful articles about the situation of refugees near the Bosnian-Croatian border (circa 2019) at their Medium site.

Remembering Youssef

Tracing the hidden violence along the EU’s external border

By Karolína Augustová for Izbjegličke priče—Refugee stories

31 May 2019 (original post)

The body of Youssef is now lying in the morgue in Drmaljevo. The police investigated an abandoned house in Velika Kladuša, where the young man was temporarily living with other migrants. The police stated that there were no traces of violence on his body, adding that the death occurred during sleep.

—excerpted from the Facebook group “Migranti BiH” (19 May 2019)

I met Youssef the first week I arrived in Velika Kladuša (Bosnia and Herzegovina). He was a tall young man, in his early twenties, very skinny, with dark black hair, and gentle contours on his face. I saw him walking in the main square, looking tired—with each step, his chin was falling. When we started talking, he occasionally closed his eyes for few seconds, but when I touched his shoulder to ensure he was fine, he opened them and continued in conversation like nothing happened. He said that he had just returned from the Croatian border, and showed me bruises and scratches around his chin, arms, and belly.

After seeing a doctor, we went for a coffee. Slowly pulling from his cigarette, he described how the Croatian authorities had caught him and violently brought him back to Bosnia—a narrative I would hear almost daily for the following eight months. The border patrols had smashed his phone, stole his money, ripped his passport apart, laughed at him when he asked for asylum, and then took him to the Bosnian border, hit him several times with batons, and shouted at him to run back to Bosnia.

Later, Youssef talked about his mother, how much he loved her. He asked if he could call her from my phone. He hid his cigarettes and said, “My mum still sees me as a small boy, she does not know I am smoking.” When the camera opened, his mother was surprised and happy to see him. Youssef attempted to give her a smile, but she started crying and told him to come home. He refused because, as he said, he left his country to help his family; not to “fail.” At the end of the call, he promised his mother that he was going to keep trying to reach Europe.

Youssef then told me that he was born in Benghazi, Libya, where his father was killed during the civil war. After his father’s death, Youssef’s mother took him to her home country, Morocco, where he occasionally worked as a waiter but struggled to find a stable job. He recalled playing football tirelessly in order to avoid thinking about a life which he described as “unemployment and misery.”

Morocco, as a former French and Spanish colony, played its own role in the current wealth of European states: a feat achieved through the poor wages and the extraction of the country’s resources, enabling the consumption of cheap products in the West. Youssef wanted to provide for his family, not for pleasure or fun, but for survival. He said that at the age of seventeen he decided to travel to Spain and find work.

While the European citizens on holiday have no struggle to legally enter Morocco and reach the country within two hours by plane, Youssef lacked legal channels and never completed his journey, after more than three years of attempts. He borrowed one hundred euros from a relative and traveled partly with smugglers and partly alone on foot through Turkey, Greece, Macedonia, Montenegro, Kosovo, Serbia, and then to Bosnia, hoping to cross to Croatia, Slovenia, Italy, and then to Spain by bus.

In the months that passed after meeting Youssef in Velika Kladuša, he told me about his sixteen other unsuccessful “games”—border crossing attempts. His “games” always left him with more marks of violence, forcing him to return to life on the streets and in different abandoned houses.

One day, we went out for a coffee in the same restaurant as always, however this time a waiter stopped us before we found our seats: “Sorry, you have to leave. Boss said no migrants here.” In the next months, we did not even try to enter a café or restaurant together as Youssef, like many others, feared the same reaction.

As time passed, I saw Youssef’s body becoming skinnier. His eyes became watery and tired and his speech became slower as well. He mumbled more. He told me one day that he was regularly using tramadol, an opioid painkiller, to forget reality for a moment. As his use of the drug developed, we began seeing less and less of each other. The last contact we had was at the beginning of winter.

Last week, I called a friend who informed me that a man in Velika Kladuša had died. She sent me Youssef’s photo, explaining that he had overdosed in a squat. Youssef’s friends said that he felt severe pain in his body while fasting during Ramadan and took an extensive amount of painkillers that killed him. Local radio and news announced that Youssef died of natural causes, as “police found no traces of violence on his body.”

Over recent days I have been remembering Youssef in my mind and tracing the everyday violence in his life that eventually killed him. Perhaps these wounds were not the type that were visible on his body in the moment of his death—however their impact was just as deadly. I have been counting all of the harms that he talked about during our interactions: hazardous games [irregular border crossings] that he took while attempting to pass through the closed transit routes and border guards; systematic pushbacks and attacks in border zones; enclosure in the harmful living environments of abandoned houses and squats; and most importantly, the fear of failing to escape these all.

Thousands of other displaced people passing along the border in Velika Kladuša — surviving, suffering, and in some cases dying — have been perturbed by the same harms. Some of these harms are perpetrated directly, when a border guard strikes open flesh with a baton and visible bruises or bleeding appears. Most of these harms, however, operate indirectly. Youssef’s loss of life reminds us how violent border systems retain the ability to kill, albeit without visible wounds.

Kafka, in his book Before the Law (1915), describes the narrative of a foreigner coming to the gate and asking a gatekeeper for admittance to the Law. The gatekeeper denies him entry and says:

“No one else could ever be admitted here, since this gate was made only for you.”

Kafka’s story, like the one of Youssef, ends with the man waiting at the gate until he dies. Both narratives show how borders are sophisticated machines. Borders inscribe laws onto a person’s body based on their skin color and place of birth, then disallow them to seek protection, locking them into harmful environments in transit zones.

Tracing the violent strategies that lead to the deaths of people on the move is crucial, as ignorance only reinforces the silent and invisible cycle of brutality behind the borders, resulting in more unseen deaths. This article attempts to trace the memories and harms that preceded the death of a young person.

Youssef was a young beautiful man who loved his family and wanted to live better; a basic motivation and wish for us all. I hope that Youssef’s memories, which I attempted to recount in this text, can bring more powerful reflections on borders than the daily news about another migrant dying without traces of violence in the Balkans.

In memory of Youssef Mchichou, born 1997 in Libya and died 2019 in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

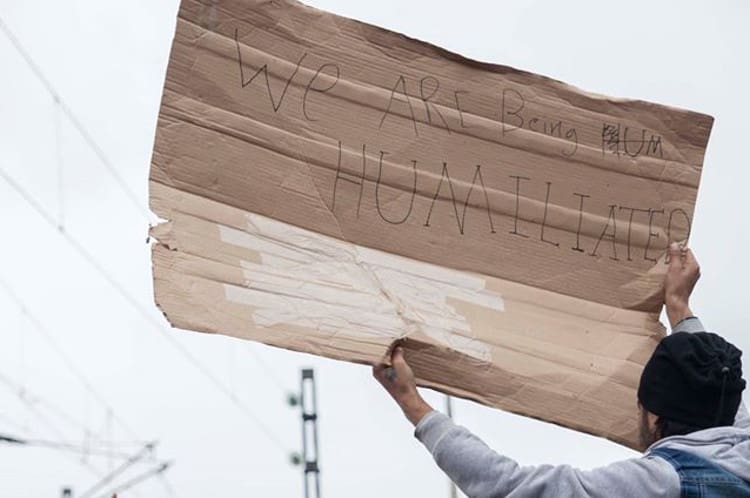

Featured image: Youssef photographed at the local radio station in Velika Kladuša