AntiNote: The following is an extended excerpt of a transcribed conversation between a Syrian and a Ukrainian, both peace activists resisting authoritarianism, imperialism, and fascist violence. The hosts of this conversation agreed to keep video and audio recordings of the event private for the safety of participants. Some names have been changed to protect speakers from state and non-state repression and retaliation.

Edited by Antidote for space and readability, published with gratitude to the speakers and hosts for their eagerness to share with our readers.

If you’re going to take one thing away from this conversation we have tonight, I hope you remember the people on the ground who are living and resisting every single day, whatever forces are trying to shut them down.

Ukraine and Syria: War and Resistance

A conversation hosted by Minnesota Alliance of Peacemakers (MAP), Citizens for Global Solutions – Minnesota (CGS-MN), and the East Side Freedom Library (St. Paul, Minnesota)

14 July 2022

Minnesota Alliance of Peacemakers (MAP) is a coalition of peace and justice groups that has been active in Minnesota for thirty years as an important venue for groups to network and exchange ideas. Their focus this year is to take action against threats to democracy in the United States.

Peter Rachleff: I want to introduce our speakers. Ramah Kudaimi is a Syrian-American activist; she currently works at the Action Center on Race and the Economy, taking on corporate complicity in Islamophobia. She has previously worked at the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights and has been a member of the national committee of the War Resisters’ League. She dreams of a world without war, militarism, and borders, and believes we can create that world through a commitment to collective liberation and transnational solidarity with all those fighting oppressive regimes and systems.

Our other speaker this evening is N. She grew up by the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, where she fell in love with seafood, volunteering, and the writings of George Orwell. N has supported hundreds of emerging leaders from Eastern Europe, Central and Southeast Asia, and the Caucasus region. She holds two master’s degrees from two different parts of the world, and is trilingual—in Ukrainian, Russian, and English.

Our first question is to both Ramah and N: if you would give a brief history of the conflict in your home country and whatever personal stories you might share about that? For this one why don’t we start with Ramah, please: the conflict in Syria and your personal connections to it.

Ramah Kudaimi: Thank you, Peter. Thanks everyone for joining us tonight. I’m really looking forward to this conversation with N and being able to talk about connections between what’s been happening in Syria and Ukraine and what that may mean for finding justice and accountability in both places.

I was born and raised outside of Chicago, but my family comes from Syria. My family is from the cities of Damascus and Hama—Damascus is the capital; Hama is a city where, under the Hafez al-Assad regime back in the eighties, a huge massacre happened. I share this because it sets the background for how I have related to my parents’ homeland and what it meant growing up knowing this history of a massacre.

At the time there had been a mini-uprising by members of the Muslim Brotherhood, and the Assad regime decided to completely destroy the city. It is estimated that tens of thousands—up to forty or fifty thousand people—were killed. And growing up, we never talked about that. It was something I knew that happened, but it wasn’t something that was talked about in my family.

Even though I wasn’t born and raised in Syria, we used to go every summer, and we automatically knew once we got on the airplane to head to Syria that we should not talk politics while there. We should just talk about how much fun we’re having with our cousins and our grandparents and uncles, but just avoid the topic of politics. Even in the United States we had to be very careful about what to speak and not speak, because you really had no idea if there was anyone spying on what was going on and reporting back to the regime.

This is the background of what Syria was like. There is sometimes confusion around what was actually the reality on the ground before the March 2011 uprising: that things were fine, it was only because of foreign interference that people rose up, and wasn’t it better then than it is now? That’s just an attempt to whitewash the reality of a very repressive state, with people living in fear all their lives, scared even of family members who might or might not be reporting on you.

To get into more of the politics: when we talk about Syria now, it’s just war. Or it doesn’t get talked about. I was trying to remember the last time I had a talk about Syria—and it’s been over a year. At the beginning I used to give talks really frequently; now it’s kind of a backdrop to a lot of other things happening in the world. Unfortunately (as anyone who’s going through a conflict will tell you), at the beginning there’s a lot of attention and then sadly it goes away. I’m sure, N, you can relate as well with Ukraine now.

But I want to bring it back, because a lot of times the conversation around Syria is either “It’s just war and it’s very sad and there are helpless refugees that we need to support,” or it’s very geopolitical: Russia and Iran versus the United States versus Assad versus all these different players, Hezbollah, Hamas, Israel, Turkey—and then no one actually talks about the people themselves. If you’re going to take one thing away from this conversation we have tonight, I hope you remember the people on the ground who are living and resisting every single day, whatever forces are trying to shut them down, pursuing demands for various simple things like freedom and justice and equality.

So I’ll take us back to March 2011: we have to remember that the context of the uprisings against all the other regimes in the region is very important. We can’t separate Syria from what was happening across the region at the time. We have to remember this even if it seems like a distant memory, considering all of the violence—at this point, people will tell you many of these uprisings “failed.” But all of the sudden we had Mohamed Bouazizi, the street vendor who set himself on fire in December of 2010 in Tunisia; protests occurred, and what is called the Jasmine Revolution happened; their president, Ben Ali, who had been in power for decades, resigned and fled. From there, uprisings moved to Egypt (where their president, Mubarak, then resigned), Libya (which also went into war), and then Yemen (which also had a resignation, more protests, and then war), Bahrain, and then Syria as well.

The Syrian people really were inspired, seeing what was happening in their neighboring countries. Youth in the city of Dera’a, which is near the Jordanian border, went out and painted freedom slogans on the wall of their city. They were arrested and tortured, and from there protests erupted, and started addressing other grievances: stagnating salaries as the cost of living was increasing sharply; a drought that was impacting people’s ability to grow crops; neoliberal policies that the regime had been putting in place, slashing subsidies while expenses rose. Then of course the regional context: people saw what other people were accomplishing and thought they could accomplish the same. They started going out and protesting.

The regime decided, as all brutal regimes do, to react with force, to attack and shut down the disturbances. They tried to shut down Dera’a, so it spread to other cities, and more people took to the streets. What the regime failed to see is that these were not isolated incidents in smaller villages that they could stop. Quickly it reached the bigger cities, like Homs and Aleppo—grievances were shared across the country.

Slowly people became very creative—and we’ll get to this later in our conversation: the creativity of people power, and how we can get inspired by that in our own context, wherever we may be today. People were trying to disrupt business-as-usual. There was a moment, in those early years, that was really beautiful. For the first roughly one-and-a-half years, people were very inspired and building their own alternatives to regime control. It was very beautiful, and we’ll get into this more.

And what did the regime and their backers do? They decided to respond with great violence. Since about 2013, the violence has continued to grow, and grow immensely, with the Assad regime, Iranian militias, and the backing of Russia (which we can also get into more), to the point now today that there have been hundreds of thousands of people killed; millions of people—about thirteen million people—have been displaced, whether internally or outside the country as refugees; we’ve had people tortured, imprisoned, under siege, and the targeting of civilians becoming the norm.

As we get into the conversation, I’m just reflecting back on these ten years, thinking about the lessons we can take from people who have continued, day in and day out, to resist, and also what we as folks who are in solidarity (with Syrians or other folks under oppression) can learn from what we failed, potentially, in Syria, to support—so we don’t repeat those mistakes elsewhere.

PR: Thank you, Ramah, thank you very much. So much history to condense and tell in so little time. Thank you.

N, please, if you would introduce us to Ukraine and your experiences.

I remember the rage inside me: it seems like the world doesn’t care—how can that be? I have no home right now! I’m an internally displaced person. I cannot go home. It’s not mine anymore. Somebody just decided that they can send ‘green men’ and take it over, and that’s it.

N: Absolutely, thank you Peter. And thank you, Ramah—I know it’s so hard to condense everything into a couple of minutes, to explain all the details. Thank you for sharing and kicking off this conversation.

I’ll start by saying I’m a little bit older than my own country, which is a rare thing in most places in the world—not so much for people of my generation in Ukraine. My country gained independence in 1991 from the Soviet Union, and a huge majority of Ukrainians voted in the referendum to gain independence (just like other Soviet republics had as well).

I remember that time a little bit—I was still small, but I remember the transition and I remember how, in my child’s mind, some of the TV channels that I used to watch were not available anymore. There was only one TV channel, that’s it, and they only operated in the mornings and evenings, and during the middle of the day there was nothing on the TV. Just some childhood memories.

I grew up in a very beautiful and challenging area that has been disputed many times—spoken about, mostly, but the reason I bring up that specific location is because it eventually played one of the key roles in the war that we have right now. I grew up in Crimea—I’m Ukrainian by nationality but Crimea is also home to an Indigenous population, the Crimean Tatars, who have been populating that area and call that area their home; they have a tragic history of persecution and deportation by the Stalin regime, and are still trying to preserve their national identity, their language.

By choice I went to my first university, which was the only Crimean Tatar university in the world. I was lucky, among the luckiest people, to be immersed in the cultural minority as a representative of a majority culture, and that opened up a lot of my horizons in learning about my land and the history of my country and all the political forces that play a role in forming our minds as young people who go to university. My grandpa, who’s Russian, and I love him dearly, refused to speak to me when he learned I decided to pursue a major in Ukrainian language and literature, and that I wanted to be a teacher of Ukrainian literature. He did not speak with me for a few months for that.

That little story is an illustration of a typical family. We have Crimean Tatars who are native to the land, and then we have decisions that were made at a political level where Crimean Tatars were deported from Crimea to Uzbekistan and Central Asia and so on, and the Russian population was moved in, assimilating and claiming the land and taking their homes. That’s the story of my family, essentially, with one side of my family having migrated from far east Russia to Crimea and deciding that’s their home, and the other side of my family Ukrainians who were born in Crimea and were part of that natural habitat, I’d say, of people mingling and sharing the resources that they have.

That shows the complexity of the diverse populations and the very gruesome decisions that were made, and that people were basically trapped in it as pawns, not necessarily always knowing how those political decisions were made, how claiming lands impacted their view on what is theirs and what is not theirs. It’s like a pre-story maybe to illustrate something that is not widely talked about in newspapers or in the media: most of the stories of families out there.

As you know, Crimea has been occupied by Russia since 2014. For me personally, when people say the war started on February 24, 2022, I say no. The war did not start then. The war started in 2014, it’s just that at the time nobody considered it as such. “It was just a couple people who died.” I say that in a morbid and sarcastic way, because every human life has precious value.

The events, as some of you might have followed, actually started in November 2013. At that time it was something called Euromaidan. Maidan is the Ukrainian word for square. In Kyiv, the capital, they have this big square, ironically called the Square of Independence. The Euromaidan started with the president then, Viktor Yanukovych, backing down on a decision to sign an agreement for political association and free trade with the European Union. At that time, a lot of students—similarly to how Ramah described: this is where the power, the civic power and the leadership is—the young people decided, no, we elected you and your government, and you’re not going to back down. That’s not what we want. We protest that. You cannot back down.

Large protests started: students were going on the Maidan and the surrounding streets, and their mothers, their fathers, their grandparents, everybody started joining. President Yanukovych’s administration sent their social riot police to suppress the protests, in the most horrific way. They beat down a lot of people, and those were just kids. We don’t really have weapons in Ukraine that citizens carry around or anything like that. These are just kids—eighteen-year-olds. And here this well-equipped Berkut is beating down these kids, and of course the mothers, the fathers, the grandmas and grandpas could not take it. So it started gaining more momentum and people started protesting this complete abuse of power and unfair display, this despicable thing that happened.

Soon enough it came to be a large civic protest, and it was not ending—people were very committed. It was a very cold winter and they were still there. My friends stood there. They were supporting each other. A lot of movement was created at that time. Eventually it led to the president, Yanukovych, fleeing the country. He abandoned everything. He abandoned his glorious house that he’d built with corrupt money that he had. He even left behind some papers incriminating him and all those things. And he left to guess where? He went to hide in Russia.

Lots of things started coming out and getting known to the public, of all the dealings and all the things that were happening. Just the fact that Yanukovych was in power was largely connected to Russia and to Vladimir Putin’s decisions on how puppet governments might work in surrounding countries and how that could help in building his empire world. When Yanukovych left, some people stepped in, but there was no specific person who was spearheading anything; the government was trying to function as it could.

A temporary government skipped in and started working, but around March of 2014, right after Yanukovych fled the country, all of the sudden in Crimea, in my land, I saw on TV reporting that some ‘strange green men’ are now walking around town, and they don’t have any identifying anything, they just wear this green uniform that looks like military but kind of not, and they have semi-automatic and automatic guns with them, and they just freely walk around. Who are these men?

The suspicion became that Russia sent troops to Crimea for some reason. Russia denied it a bazillion times, essentially until there was no denial anymore, and as you might or might not know, in Crimea, in Sevastopol, which is the Black Sea port city, historically (for some reason unknown to me) we had the Russian Black Sea fleet. That made it very easy for Russia to quickly turn things over and claim that they had come to “save” the Russian-speaking population in Crimea.

Looking back to the story of my family and my grandpa: the majority of the population is Russian-speaking. I grew up speaking Russian as my first language. Absolutely everybody speaks Russian there, and nobody has ever been persecuted because of the language that they speak. There was no need to protect anybody; that was just an excuse that Putin had in is mind to claim that all of these ‘green men’ are there to protect somebody.

I’m sitting a lot in this “old news,” so to speak, but that’s because it is largely forgotten. But it’s a story that teaches us, as the world, to know when we should react: sooner, to prevent many deaths in the future. But moving forward, Russia took over Crimea. They did a pseudo-referendum which was completely unlawful, and there was not even a question whether or not Crimea was going to remain under Ukraine. Rather, it was: “Do you want to be with Russia or do you not want to be with Russia?” Furthermore, it’s against the constitution of Ukraine to hold a referendum without letting all citizens of Ukraine take part in a decision around the territorial integrity of the country. Essentially Putin claimed Crimea, and he turned it into part of Russian territory in 2014.

At that time, I was living in Kyiv but I saw how, slowly, first the trains stopped going there, the planes stopped going there. It was very difficult to get there. It was very scary crossing borders, not very safe to visit family. It was a very difficult time. I remember the rage inside me that nobody cares: it seems like the world doesn’t care—how can that be? I have no home right now! I’m an internally displaced person. I cannot go home. It’s not mine anymore. Somebody just decided that they can send ‘green men’ and take it over, and that’s it.

It was difficult for many people, especially younger people. And soon after the Crimean occupation, Russia started thinking about grabbing some of eastern Ukraine in addition to that as well. In the Donbas region, which consists of two oblasts of Ukraine, some pseudo-separatists started popping up and saying, “We need to declare our own republic here.” The reason I’m saying “pseudo” separatists is because we don’t have any ethnic, national, religious, or any thing that would separate them from anybody in Ukraine. But when a couple of people like that started doing their own thing, soon enough the world saw that the Russian military and Russian big money were backing them up. Soon enough it was proven and discovered that it’s not really Ukrainian “separatists” trying to break off from Ukraine, it’s Russia trying to find puppets in Ukraine to claim more land, just like they did with Crimea.

2014 is when Ukrainians consider the Russian war on Ukraine to have officially started. It started with Russia bringing military equipment and soldiers to fight on Ukrainian territory, and covering it up with the pseudo-separatists. Lots of lives were lost at that time, and fighting was happening, and Ukraine did what they could. We had elections; government changed; people grew in their understanding of their civic rights and the power that they have, as well as their collective voice. Good changes, bad changes, we saw it all.

This brings us to February 24, 2022, as the whole world saw Russia sending missiles into apartment buildings in places like Kyiv, and to the events of yesterday when they gruesomely, morbidly, sent their rockets into Vinnitsa, a place that was absolutely no military threat. It was a completely civilian object, with people walking around and just going about their day. The terror that is happening and what Russia is doing in Ukraine right now—I could go on and on about it. But in the minds of many Ukrainians, it makes us wonder: is Putin’s appetite to eradicate all Ukrainians? Is this a genocide going on right now? Does he just not want us to exist? Do we bother him somehow? Do we prevent him from claiming his greatness in his Russian empire, and that’s why he’s doing it?

It’s very hard to justify or understand the reason why. Why would he just kill civilians in central Ukraine, far away from front lines? I cannot understand it. Not many human beings could. But here is where we are right now.

PR: Thank you, N.

We have certainly seen violence on the television screens, the violence visited on civilians. It’s an area that we might talk more about tonight if people are interested. But I feel that we’ve been inundated with images of it. What we haven’t seen much of is the organizing on the ground in Syria and in Ukraine. Both of you have pointed to the activism of young people, and how young people have brought their families into struggles; the ethnic diversities and the role that that’s played.

So I want to ask you to talk a little bit more specifically about the organizing that you know about that’s going on in both places. Again I’ll go back to Ramah, if you would start, please.

It was a beautiful moment, because there was this flourishing of freedom of expression that, again, hadn’t been seen in Syria for decades. People really starting to imagine what happens after the regime falls.

RK: I appreciate this question, because again, the violence is there, it’s in the news: here are the numbers dead, here are the potential war crimes, here are the hospitals bombed, the markets bombed. We’ve become desensitized to this, globally. And yet there is so much that people are doing on the ground, and a lot of creative actions.

A lot of things happened in the past, and the regime expelled activists, killed them, imprisoned them, tortured them. And their focus has been on the people who do this type of action, the civil disobedience, the creative action. They know that’s where the power is. They would rather get rid of those people than, say, people who are taking up arms. We can get into discussions of resistance and what that means, but they know there is an edge to people who are thinking more creatively and building alternate modes of power, because it takes a lot more community effort and conversations.

In Syria, again, we’re talking about a society that was highly controlled by the regime. There was only one political party. The president was in power for decades, and when he passed, the son came to power and stayed for now twenty years. We’re talking about a society that has been propagandized to believe this is the one and only way to do things. So the moment there was any sort of freedom, it flourished. People flourished in their creativity.

The music, the poetry that came out in those early days of the revolution! There was a singer called Qashoush, who was killed back in July 2011, who came up with the song “Come On, Leave Bashar.” If you listened to any of the protests in the beginning, that was the big song, alongside “The People Want the Fall of the Regime,” which had become the anthem of all the revolutions across the region. We saw genres like hip-hop and rap really grow too—it’s not only what we would consider Arabic music, but other genres that people had obviously listened to from uprisings across the globe throughout history.

People did sit-ins and strikes; businesses shut down their stores. Students took action on their campuses. The reclaiming of public space—again, in the past people who were afraid to even gather in a group of five people, because that could automatically mean getting thrown in jail. They were reclaiming that, and saying, “No, this is now ours.”

There was one activist, Ghiyath Matar, also killed in September 2011, who in Darayya (another city that was a central part of the revolution) would give out roses to the soldiers, begging them to defect. They would put songs like “Come On, Leave Bashar” in cassette players and put them in black bags in garbage cans across the cities to annoy the soldiers in the area. There was a political artist, Ali Farzat, who drew political cartoons—his hands were broken in August 2011. There was a lot of visual art and theater: banners, cartoons, signs, leaflets, skits and vigils, anything. The creativity was amazing.

And people also thought, “These types of actions aren’t enough, we also have to build alternate ways to function as a society.” If we’re going to get rid of the regime, what is going to come in and replace it? People started thinking about that. It’s a big question to ask. If you get rid of the regime, what’s going to happen? There were a ton of things happening on the ground. People were creating local coordination councils, neighborhood councils of people deciding, “Hey, this is how we’re going to conduct our business now as a neighborhood.” People were creating new space for grassroots organizing and politics—creating, again, what the state had failed to provide for decades.

New media outlets were sprouting up, like the Enab Baladi newspaper, or Radio Fresh. If you’ve seen the pictures in Kafranbel of people holding signs over the years, people with a message to the world—the founder of Radio Fresh was one of the main activists helping with those signs. Raed Fares was also killed, unfortunately, a few years ago. People were creating new libraries where people could come and borrow each other’s books and discuss things. It was a beautiful moment, because there was this flourishing of freedom of expression that, again, hadn’t been seen in Syria for decades. People really starting to imagine what happens after the regime falls.

Again, it’s unfortunate, because the discussion ends up being about what the international community should do or not do, or about terrorism and using War on Terror language—who is Russia bombing today, who is the US bombing today, who is Turkey bombing today, who is Israel bombing today? The reality is yes, there is that bigger geopolitical game that has been happening in Syria and continues to happen in Syria, to the detriment of the people of Syria. Because the people of Syria were clear on their demands. It doesn’t mean it was ever going to be easy, it doesn’t mean that everything was going to click into place. But if people had been paying more attention to what was happening on the ground there in the early days, I imagine things may have turned out a little bit differently than where we are now, where unfortunately a lot of the violence is so wretched that people just lose the facts of what happened early on.

One more thing: even though this violence is awful, you should know that protests still continue against the regime and all parties that do not abide by the revolution’s values of freedom and dignity—whether it’s armed groups that came in and took advantage of the revolution, the regime itself, or other militias backed by other countries. Every March, the anniversary of the start of the revolution, people are out in the streets, particularly in Idlib, which is still not under regime control. They make it clear: our demand is still the same, the fall of the regime. That’s that spirit of continuing to resist. As long as you’re resisting you’re not actually defeated. It’s something hopefully that we can support in some way or another.

PR: Thank you, Ramah. It’s so important for us to hear these stories that we see so little reflected and expressed in the media.

N, what can you share with us?

Local volunteers, local people who refused to just watch what’s going to happen, decided to do some action. They were taking care of people—disabled people, elderly people who did not have access to anything, or were trapped in their apartments, or trapped in the bomb shelters, and did not have access to water or food. Volunteers took it upon themselves to coordinate things as they could.

N: Yes, thank you, and thank you Ramah for the inspiration and the reminder to move beyond the headlines. I’ll just start with saying that my husband does not speak Ukrainian or Russian, so just by seeing what kind of news he gets, I usually can judge what the rest of the world gets. Very often, he’s like, “What is going on? Why is it so silent?” He asks me for information, for the news. And that’s where most of those beautiful reflections of civilian resistance and camaraderie come out: it’s from those stories that we get from our friends, our neighbors, our people. We just need more of that. I really respect you putting together this event so we could have a platform to remind people everywhere that we’re human beings who love their countries and want to preserve our national identity, and we are doing what we can through arts, through volunteering, or other things.

When the full-scale invasion by Russia started on February 24 this year, people were in disbelief for the most part, and a lot of people were not prepared for anything that would come. In the first few days, I was also in shock. But very quickly, somehow, this resilience and this tenacity kicked in for a lot of people, and people started caring for their own communities, their neighbors, their people. We created a chat for some of our alumni and participants in some of these programs between Minnesota and Ukraine. We then started adding other people that we know, trusted people. In that chat we were very reactive at first: people were saying, “Somebody needs immediate attention over here, do you know anybody?” But we were playing this role of connecting and trying to find resources.

In the first few days, as you probably saw, the Ukrainian government made the decision to give out weapons, basically as many weapons as Ukraine had, to civilians who decided to come in and help the army. The forces were so uneven, it was mind-boggling, so people were very scared, and all the attention was to support the army.

Then, through that little chat that we created—and I know there were probably millions of chats like this, of people who cared, that started elsewhere—slowly, what I saw happening was local volunteers, local people who refused to just watch what’s going to happen, decided to do some action. They were taking care of people—disabled people, elderly people who did not have access to anything, or were trapped in their apartments, or trapped in the bomb shelters, and did not have access to water or food. Volunteers took it upon themselves to coordinate things as they could, get the little fuel that they had in their cars and figure out who has what. We started working on supporting over a dozen communities across the front lines, in the occupied territories and in territories that soon became occupied, additionally, and the front lines essentially, throughout the southeast. It was one trouble to another.

A couple months in, with all the advertisements all over the internet with international organizations asking for donations, I’m talking to dozens of Ukrainian leaders doing what they can, and they’ve seen nothing of that help. Maybe it’s somewhere there, I’m not claiming to know, I’m just saying that something was ridiculously broken. It broke my heart; I had my trust in some of those international organizations that have big names, and most Americans do too, but this full-scale war and our work helping our people in Ukraine opened up my eyes to the fact that we are ourselves empowered individuals and we can do what we can to help each other, not relying necessarily on international aid as much—and at the same time we can remind people around us: instead of donating to international aid organizations, seek out the local organizations that you know personally or your friend knows personally, and donate there. That’s where the help is needed.

For the most part, in the city of Mykolaiv, which is a southern city that is currently being shelled almost every day, and it’s very close to Kherson, which is now occupied by Russia—at some point Russians shut down any access to clean drinking water there, and the whole city is not getting water. I was writing everywhere I could trying to figure out what to do, how to help, where to go—people were forced to get water from the river, which is polluted already. I was thinking: if only all these Americans who kindheartedly donated their funds to all of those places knew that aid does not get to Mykolaiv because it’s under heavy shelling and bombs every day! No aid organization is going to put their train there.

But my friend and I are able to send money to our volunteer there who is able to purchase water filters and provide them to people. Working through a lot of frustration and disillusionment of all sorts, together we found a way to connect rotary clubs, connect other funding, raise our own funds as well, and help provide volunteers on the front lines with supplies to purify water from the river. People were telling us that without it they didn’t have anything to drink.

Twice a week we hold meetings with our Ukrainian and other partners, to talk about needs and opportunities and the ways we can work together and support each other. The needs change from one week to the next. All of the sudden Ukraine is out of salt—how in the hell are we going to find out how to transport salt? And then the next week they’re out of gas and now everybody needs to buy bicycles to deliver salt or water. It’s almost comical, if it weren’t so tragic.

But through this experience I learned there is no limit to creativity. That’s how people work. They’ve empowered themselves. Okay, it’s scary, we don’t know anything…I didn’t know the first thing about water filters, but I’ll try and figure it out because I care about people who depend on it.

This is just our community doing things, and there are many communities like that. What is so powerful about people coming together this way is that there was no “my child” or “your child,” it’s “our children.” There is no “your grandma” or “their grandma,” it’s “our grandma.” People do all they can to feed each other, share what they have. That sense of togetherness and unity, more than anything, scares Russians.

PR: Thank you. I’m so struck that you used the terms comical and tragic. I think what I’m hearing tonight is inspirational, coming from both of you. And it doesn’t mean the situations aren’t tragic and it doesn’t mean there isn’t evil at work. But the inspiration of our neighbors, of our extended families, of the people we know working with each other and helping each other—that there is a new world inside this monstrosity that exists in Syria and Ukraine and in so many parts of the world. There is a new world. And you’re both helping us see it tonight, and I’m very moved and appreciative.

I hate to go to the negative, but I do also want to think a little bit about how the dominant media not only leaves stuff out, but also circulates lies and misrepresentations. The people who you’ve both been talking about tonight, helping each other and caring for their neighbors, are described as “terrorists” and “Nazis” and “al-Qaeda.” I wonder if you would like to address those misrepresentations that have gotten in the way of our seeing the kinds of stories that you’ve been telling.

Ramah, please.

The conspiracies that came out of Syria were absurd and comical. We would laugh at them if it didn’t mean people were actually being killed because of this.

RK: Thanks, Peter. I think it’s important to talk about this, because again there are lessons here for how we deal with other spaces and demands for solidarity. I’ll focus a little bit on Syria and do some comparisons between Syria and Ukraine that are also important to think about.

When I started organizing and thinking about what it means for folks in the States to be in solidarity with Syria, it was very difficult. I’ve talked about this in the past with folks on this call. There’s a problem on the left when it comes to thinking about geopolitics, imagining a different world and not falling into what many folks define as campism, or the idea that the enemy of my enemy is my friend. For several years in Syria, it was a lot. It was very hard to organize solidarity when you had to cut through the propaganda from the regime that was then amplified by Russia, and then amplified by bots on social media. If you compare the first few years of the revolution to later when Russia really amped up their support for the regime, the destruction of the discourse online was immediate. There’s a lot to dive through.

In addition to that, there has been confusion among antiwar folks, leftists, and progressives in the US wondering what they’re supposed to believe. That was the whole purpose of Assad’s and Russian propaganda, to get you to the point where you don’t know what’s true and what’s not, so you just resign yourself and don’t engage. That was a big problem. It continues to be a big problem. Again, there’s a point in that: don’t think about this regime, don’t create solidarity, don’t think about solidarity with the Syrian people. Instead, just say, “It’s complicated! We don’t really know who did this chemical weapons attack! Aren’t they all terrorists anyway?” All of the sudden there were progressives in the US—who should understand that the War on Terror is a problematic concept—saying “it’s different in Syria; those are really terrorists who should be attacked.”

I would push people, again, to listen. You have to listen to leftists, and particularly Syrian leftists, when you’re thinking about this. It’s not, “My local communist said XYZ.” Okay, that’s what they’re saying. What are the people on the ground, the people who have experience, saying?

Another difficulty is: what do you do when a situation does become armed and things get messier? The reality in Syria is that yes, things took a turn. The responsibility is on the regime—it’s still on the regime. But the fact is that at some point or another, there were so many different armed groups fighting on the ground. What, then, is solidarity? Imagining what the difference is, what solidarity means at this moment in time—I see people talk about mutual aid networks, and how they continue to support activists who are being thrown out of the country, tortured, imprisoned.

One thing I would tell people to think about is that there are demands that are going to be demands no matter what, such as demanding accountability for all war crimes. It doesn’t matter if it’s the US, or Israel, or Turkey, or Iran, or Russia, or whatever armed group. You can make an overall demand that we need accountability for war crimes. These sieges that the regime would do, or the carpet-bombing. The barrel bombing. These are war crimes. Bombing of hospitals—we can’t even agree on these certain things? We couldn’t, because people were like, “Well, I don’t believe this is true.”

Or the demand for freedom for political prisoners. That’s something that people across the globe should be thinking about. What is the role of prisoners and mass imprisonment? Again, there are bigger ways that we can make demands that don’t have to get into the nitty-gritty. You don’t need to get into the nitty-gritty as a solidarity activist. You know your solidarity is with demands of freedom and justice and accountability. Don’t let the messiness take you away from being able to say that clearly. Victims do not need to be perfect for you to get in solidarity with them. But we got complicated, like, “We don’t actually know: I saw this picture of a Syrian activist with this rightwing politician!” and all of a sudden that meant the entire revolution was some rightwing conspiracy. That’s not how things work on the ground. People have agency.

The other part of it is just that: people didn’t understand agency. “This is just a CIA conspiracy; this is a Zionist conspiracy; this is a Soros conspiracy; this is an al-Jazeera conspiracy!” The conspiracies that came out of Syria were absurd and comical, like N was saying. We would laugh at them if didn’t mean people were actually being killed because of this. Again, our role is to respect the agency of people. When people are saying, “This is what I’m dealing with; these are my demands, you need to figure out a way to help me in these demands,” then it’s back on us to figure it out. Not to act like, “Well, I have no idea what to do,” and just sit—or even worse, buy into the propaganda and disinformation.

The last thing I’ll add: I’ve been thinking a lot about how Ukraine and Syria have similarities, most obviously in terms of Russia being one of the main belligerents. But there are also very clear differences. Ukraine is a country that’s being occupied—that’s different than a people rising up against their dictator. And then, unfortunately, the way the world has reacted has also shown the Islamophobia of the world, the anti-Arab racism. Compare the welcoming of Ukrainian refugees across Europe to how Syrian refugees or Afghan refugees or others were received—it’s like, wow, they’re really fine being this openly racist and Islamophobic. These are countries that just a few months ago were letting Syrian refugees freeze at their borders, in the forest (Poland for example), now opening their arms to Ukrainian refugees. In the US, Biden gave the Title 42 exception to only Ukrainians, while for everyone else it was, “Nope, you still can’t enter.” That’s a reality.

Or if we look at the swell in boycotts and sanctions talk. We can discuss the reality: why it took so long for actual sanctions against Russian oil, or the impact of people saying they’re going to boycott XYZ corporations or “boycott Russia.” I used to do BDS campaigns in support of Palestine. These corporations just pretend they don’t have anything to do with it. Do you see the hypocrisy? When you are saying, “We need to push, we need to isolate Russia”—Russia, as it was bombing Syria, hosted the World Cup and the Olympics in the past few years. No talk about isolating Russia happened at that time.

I do work now around tech corporations and the role tech corporations play in helping spread disinformation and propaganda. Again, companies like YouTube are now claiming they are going to “take Russian propaganda seriously” on their platform. Awesome! I have seen plenty of anti-Syrian-people propaganda. These accounts have been posting for years. You all took no action.

Still, it’s important for us not to use these moments, seeing the different reactions, to say Ukrainians don’t deserve this aid. I’m glad you all are taking these actions for Ukraine. Ideally, in the future you will take them in support of other people as well.

PR: Thank you, Ramah. N?

It’s very difficult for me as an intellectual human being to overcome a sense of dissatisfaction with the way people use their brains. It’s very unfortunate, and I think we just need to talk about it more and teach critical thinking, identify facts, and learn history.

N: When I think of propaganda—there is a whole science out there, and some journalists who might be on this call might be interested in this and already studying the subject. There are plenty of examples in history. Ramah just shared some, and we have some from World War Two as well. But the essence of it that many people do not know—and I feel everybody needs to be educated on this—is that propaganda is not about saying something that is completely untrue and repeating it over and over (although the trolls on the internet do that sometimes). The point is to make it half-true, half false, put the story out, and make people doubt, and make people disoriented. Then put out another story debunking that first story but then adding something else to it. And then the third one, and the fourth one—there comes be so much of it that everyday people, who are worried about bringing food on their table and feeding their children, are not going to look into the intricacies of who was right, who was wrong. That’s the role of propaganda: for people to stop thinking, stop trusting anything, and stop digging and trying to find the truth.

People are like, “Who knows? It’s all relative, right?” That’s what propaganda is aiming to do, for people to say, “Who knows nowadays who’s right and who’s wrong? There is no truth out there! Maybe this is half the truth and that is half the truth.” In reality, in some cases there is very much a fine line for what is right and what is wrong, what is truth and what is not, and the benefit of the doubt should not be given.

That’s what we’ve witnessed in Ukraine. Although I do understand, just from being here, that in the United States it’s very clear how many people here support Ukraine and do not buy into Russian propaganda. We cannot say the same about other conflicts out there, obviously. But it’s been worse for people who are in the predominately Russian-speaking population—Russia could not figure out or does not have enough money to use their propaganda on the English speaking world as much. They are trying to, and there are some English-speaking TV channels that are doing that. But they are most successful in the Russian-speaking media world.

It is sometimes very strange to me how people could believe certain things, and it’s difficult for me to talk to my own family, when they’re telling me “Bucha was staged.” No, my friend actually escaped from there two days before it happened. They were sitting in the bomb shelter because they were afraid to go out. It’s just hard. The difficulty of the propaganda and the way it impacts people is that people would rather step away from learning anything, from believing their own daughter or their own sister or their own brother or relative who is calling them and saying, “I’m sitting in a bomb shelter right now and the Russian missiles are hitting my house. I do not know when I’m going to have water or food,” and their relative in Russia would say, “That’s nonsense. You’re making it up.”

Stories like that—I don’t know. It’s very difficult for me as an intellectual human being to overcome a sense of dissatisfaction with the way people use their brains. It’s very unfortunate, and I think we just need to talk about it more and teach critical thinking, and identify facts, learn history, and learn examples of propaganda from history, too.

In terms of the support that the world is giving and not giving: it’s a shame. Definitely, the world picks and chooses who to help and who not to help. A lot of politics play a role in that, obviously, geopolitics, and this is terrible. But the lesson I got from helping people figure out how to evacuate or move away from danger, and being frustrated with the fact that they cannot navigate bureaucracies of other countries, even with the doors seemingly open to them, is that it’s still not very easy. What I learned is to rely on the fact that nobody owes me anything and I do not owe anything to anyone. That’s a very scary principle to admit, but unfortunately it’s a very sane mentality that can get people through the day, and from a dangerous place to a better place, hopefully.

But it’s a shame that we’re not doing more as a community to stop segregating people into black and white, asking who deserves more. There is no such thing. There is one Earth, it’s the same air we breathe. We have our own histories to share, and our pain to add, and we need to come and recognize those things, and not segregate people more. That’s the whole reason why we are having these wars. I don’t understand how this is not clear for many people, but to me personally it is clear. For as long as we are trying to call somebody a second-class citizen or trying to give them less than people deserve, that’s how long we are going to have war and conflict and the struggle to grab power.

PR: Thank you, N.

It’s been moving to me to hear terms like mutual aid and solidarity being used in the cases of Syria and Ukraine, when many of us here in the Twin Cities have also been talking and trying to practice solidarity and mutual aid since the murder of George Floyd, if not before. So I think we’re all connected in all these ways.

There was a question about prisoners and also about Ukrainians being forced to relocate to Russia. These seem like particularly egregious stories already within a horror story. I wonder, N, can you address what it is that we’re hearing about Ukrainians being forced to move to Russia? And then Ramah, maybe you can say a little bit about people imprisoned in Syria.

N, please.

N: Yes, absolutely. Thank you for this question. Again, it’s not talked about in the media, largely. But essentially, when people get trapped in territory that Russia has been able to claim and occupy since February 24 this year, people are restricted in their movement—they’re not able to leave. They’re not able to go into Ukrainian territory. And the Russians are not stopping at just occupying territories, they are looking for “spies,” looking for “Nazis,” looking for whatever the heck they are looking for. They are persecuting and looking for people that might have a Ukrainian flag in their house, which for them would be considered Nazi or whatever. So some people fear for their lives, but they are not able to safely leave. Some people tried to escape through Russia and then through Georgia or other areas. It’s very dangerous to do, and it’s basically your own risk, whatever may happen.

This is just the cases of people who are willingly leaving; the only route to escape back to Ukraine is through Russia and then through Georgia or Armenia or other places, and back to Ukraine through Europe. But then there are cases where people are just forcibly deported to Russia. In Mariupol, the very tragic city as you might know, whenever there were evacuation corridors agreed upon with Russia, instead of letting people choose where they want to go, they just channeled everybody to Russia. We have accounts of specific filtration camps that Russia set up on their territory to filter those Ukrainians and check them, search them, question them, do whatever to them, to identify if they are Nazis, essentially.

We also know cases of a lot of children being trafficked—let’s call it as it is—to Russia without any permissions, usually, and also they are children whose families Russian soldiers killed in the first place. That’s a big issue that Ukraine will have to somehow figure out how to address. For the most part we know that, in cases when Russia deports people, they try and spread them around Russia, as far and wide as possible, from Rostov all the way into the far east or Siberia. They spread them around as much as possible, which makes it financially or logistically impossible for people to get back, because they normally don’t have any money.

It’s very tragic. And it’s a subtle way to kill the nation, essentially, and to disrupt people’s lives and disrupt any faith and any humanity overall, I’d say. It’s one more cruel way that adds to killing.

PR: Thank you. And Ramah, about the imprisonment of people within Syria?

Prisoners seem to be something in all societies, and the way they are tortured and mistreated is something that people are waking up to more and more. I think there is an opening there, potentially, to talk about political prisoners across our different contexts, and how we can fight on their behalf.

RK: The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights does really good work in terms of data on awful things in Syria. In their latest tracking of arbitrary arrests and forced disappearance, they estimate that 150,000-plus people are still in prison, or families may not know where they are but they know they’ve been forcibly disappeared. The overwhelming number of those people were disappeared by the regime. The regime’s prisons, even before 2011, were notorious for the torture that happened in them. Again, this was a police state.

Every couple of months, news trickles out about the regime calling people to tell them, “Yeah, your loved one is dead,” and they didn’t know, and they don’t get any more information. Or there will be a massive release. A few months ago, a lot of people were suddenly released from prisons, and there was confusion about what exactly the regime was trying to do by that. Again, these are methods of genocide. It’s trying to harm society. How do you harm society? You separate people from their families. We know this, we’re living through it in the US as well. Causing confusion for people—not knowing whether your loved one is dead or alive is a big problem.

There’s another group of Syrian families called Families for Freedom that is also focused primarily on Syrian political prisoners. Again, the issue of political prisoners is something I bring up when people say they don’t know how to relate. I’m like, well, prisoners seem to be something in all societies, and the way they are tortured and mistreated is something that people are waking up to more and more. I think there is an opening there, potentially, to talk about political prisoners across our different contexts, and how we can fight on their behalf.

Again, it’s a big problem that existed pre-revolution. One big impetus for people to rise up in the early days was the story of a child who was twelve or thirteen at the time, Hamza al-Khateeb, who left his house, went out to protest, and was imprisoned for some time—his body was returned to his parents in awful condition of torture, and people saw. Those pictures circulated, and threw people more into the streets. The youth of Dera’a who went out and wrote “You Stole Our Future” were also imprisoned and tortured—it’s awful, I’m not going to go into details of the torture. But that also was an impetus for people to take to the streets. So there is something there. People need to understand why people take risks to go out and protest, and then get tortured in those prisons, and then people rise up more.

PR: It’s been inspiring tonight to hear from Ramah and N, and also to see how many people have come together to try to find positive ways that we can contribute to peace and justice in the world.

N, you’ve raised your hand, go ahead please.

N: Thank you, Peter. I just wanted to add: if you have the opportunity to meet Ukrainians or Syrians who do events or visit your state or your city, do that. That’s the way to connect, to relate. That’s the way we contribute to stopping the war, by having personal connections. My team I mentioned, by the way: we are full volunteers doing things pro bono, we have day jobs, but this is just something we do. We are hoping to host eighteen Ukrainian young leaders in Minnesota this August and September, so we’re working day and night to be able to bring them here for an amazing experience of five weeks in Minnesota.

We are still in the process of securing visas for that, but you can find information on our website, and if you want to join in, if you do a potluck or open air event, we would love to see you. Meet these children, talk to them, hear their stories, share about your story. They are extremely excited, they want to see the world and meet other people and tell them about Ukraine, how much they love their country, how much they want peace.

I think communications and meetings like that are what make us more relatable to each other, and make us think more about choices we make—and hopefully can be a way to stop war and stop the atrocity that it brings to so many lives.

PR: Ramah, do you have a parting comment?

RK: Yeah, thanks, and I’m really honored that you all organized this, and wonderful to be in conversation with you, N.

One thing for people: you don’t need to be like, “Oh my god, I’m busy, and now I have to add Syria to my plate, or Ukraine to my plate.” I’m sure you all are doing amazing work around social justice issues, around accountability. Even having conversations about these two places within your work is powerful in and of itself. We’re not sharing our stories for people to be like, “Oh my god, I don’t have the capacity.” We’re all busy. I know that. We’re all doing such amazing work. But solidarity can be as simple as: okay, we’re talking about labor unions here? Let’s talk about labor in Syria. Let’s talk about labor in Ukraine and what that means. We’re talking about mass imprisonment? Let’s talk about that. We’re talking about surveillance and so on—you can connect literally any issue you’re working on to the issues that Ukraine and Syria are bringing up. And that in itself is so important.

PR: Thank you everyone. Keep up the struggle. Stay well. Thank you, goodnight.

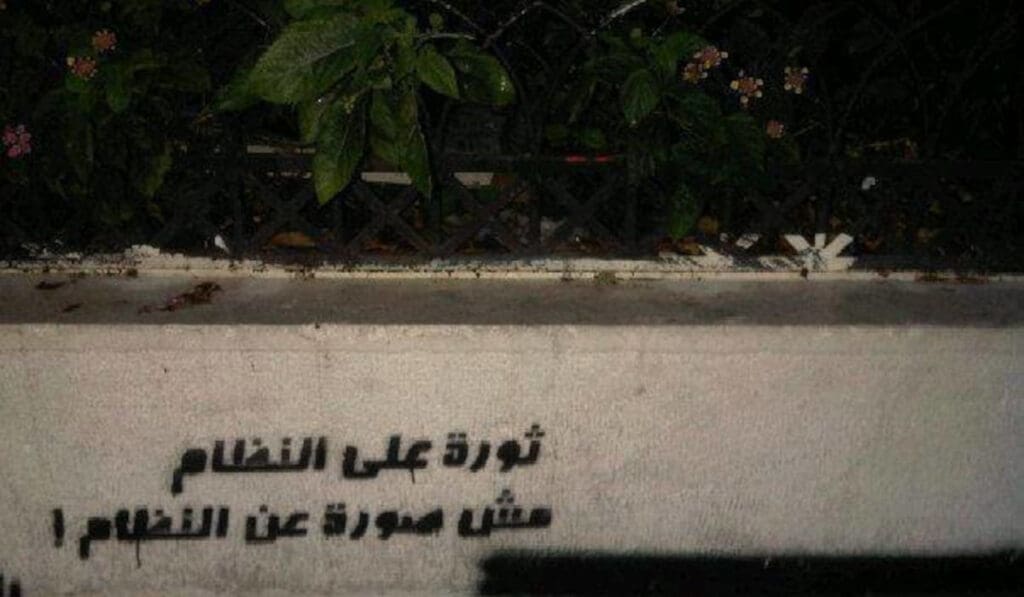

Featured image: Ukraine solidarity mural being painted by Aziz Al-Asmar and friends in Binnish, Idlib, Syria. They are the same revolutionary Syrian artists who made the mural in solidarity with the worldwide George Floyd uprisings in 2020.