AntiNote: This is another gray translation of a highbrow commercial media article from Switzerland, by the same investigative reporter who broke the Cambridge Analytica story in late 2016 – the unauthorized translation of which was and remains Antidote’s most-read article of all time.

Hannes Grassegger’s intrepid reporting first appeared, as usual,* in Das Magazin, which we in 2017 compared to the New Yorker as context for readers in English. It’s probably more similar to the New York Times Magazine, upon further consideration. It arrives to subscribers with the Sunday print edition of Zurich’s Tages-Anzeiger newspaper each week.

The magazine, like its US counterparts, is paywalled. This story was long enough in the making, however, that Grassegger cross-posted it on his own website to broaden its reach. This was the source we used for the translation.

As for the substance of the piece – Grassegger’s subtitle and lede don’t leave much to discuss. It’s about a massive shift in international and national jurisprudence – which could also be described as the hijacking of such – the full consequences of which have yet to play out.

* Hannes Grassegger has since left Das Magazin and co-founded an experimental crowd-sourcing news network, Polaris News, in Switzerland.

The Man Who Knows No Boundaries

The wrong passport can be the end of you—but if you have enough money, this man can get you the right one. On the move with the Passport King: the Swiss man who built the global passport industry, and turned citizenship into a commodity.

by Hannes Grassegger for Das Magazin (Switzerland)

10 December 2022 (Originalversion auf Deutsch)

1. Encounter in a cellar bar

I first met the Passport King at a birthday party in a cellar bar in Klosters, just before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began. Standing between the bar and a cluster of shiny gold helium balloons shaped like the Bitcoin logo, in the wee hours of the morning, I noticed a slender gentleman in a suit coat. He had a hawkish face, light blue eyes, his gray-blond hair combed back. In contrast to many other guests, he was not wearing an expensive watch. We came into conversation.

He introduced himself as Chris, and explained that he was an attorney working in constitutional law. He had a monogram pin in the buttonhole of his lapel: H&P, in silver letters. When we were saying farewell, he gave me his card, upon which was printed in embossed charcoal letters: “Henley & Partners, Dr. Christian H. Kälin, Group Chairman.”

In the months that followed, I spent a lot of time with Christian Kälin. I learned from him how to get a passport for money, and where. He brought me along to negotiations with top state officials and showed me how he had built a worldwide business in citizenships from his office in Zurich, to the point that his company has essentially become a central passport administration for rich people.

Recently I caught word of his plan to sell even the Swiss passport. Although: I should not under any circumstances write it that way. “Selling” is totally the wrong word for it, he told me. But first, a couple basics.

2. What is a passport?

What is a passport, actually? There are two answers to this; two sides of the same story.

Both start in the same place: a passport is the official documentation of an individual’s belonging to a state. Determining the criteria by which someone may belong is the sole and exclusive sovereign prerogative of the state.

Passports are a relatively new invention. Visa requirements – and the concomitant requirement to prove citizenship – were only introduced in the mid-twentieth century.

In one telling, it’s all about protection and access. Passports developed out of so-called Geleitbriefen or diplomatic letters – promises of safe passage for noblemen or emissaries. The word passport comes from “passage” and “porta,” meaning gate. It promises access: when we show our passport, we are allowed to pass a boundary. Conversely, a passport is also a guarantee of readmittance upon returning home. The assurance that your country will accept and protect you. Citizenship, upon which passports are based, goes even deeper. It is “the right to have rights,” as the philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote. Only a citizen has claim to the full set of rights that a given country offers; in democratic countries, for example, the right to vote.

The spread of passports in the twentieth century appeared, in this first telling, as a promise of equal rights.

The other telling begins with an observation: passports create boundaries. In 1942, the author Stefan Zweig described the time before passports this way: “Before 1914, the Earth belonged to all people. Anyone could go wherever they wanted and stay as long as they wanted. There were no permissions and no prohibitions, and I am endlessly amused by the amazement of younger people when I tell them that before 1914, I traveled to India and America without having a passport.”

Birth is a passport lottery, writes the researcher Ayelet Shachar – and the vast majority of humanity are losers. A Swiss passport opens doors, and gates, worldwide. Switzerland sends charter flights and diplomats to rescue its citizens, it gets them evacuated, cares for them. Other states hack off the limbs of some of their citizens, hunt them around the world and murder them, such as Iran, Russia, or Saudi Arabia. The dictatorship in mainland China, moreover, has ceased granting passports without special dispensation; it has locked its population in.

The result is that many people would rather have a different passport. But that is difficult. Less than two percent of people receive new citizenship over the course of their lives. Ordinarily, one receives citizenship through birth. Either from your parents – “Ius Sanguinis” or Law of Blood – or from the place or country of birth – “Ius Solis” or Law of Land. Attaining new citizenship, so-called “naturalization,” isn’t easy in any country. It is not unusual to have to live in a country for as long as ten years, master the language, and be able to support yourself financially, in order to attain citizenship.

But there are exceptions. Because citizenship is actually an unregulated sector. There is no supreme global authority and no worldwide passport register. Every country writes its own rules regarding whom it will grant citizenship and whom it will not. This is where the business model for a passport broker begins, and this is where Christian Kälin comes in, as he explained it to me. But first, a very current example.

3. How Russians turn into Turks

When the full-scale war in Ukraine began, many Russians suspected that the situation in their home country would get harder, so they decided to become Turks. This was relatively simple. They just bought Turkish passports. Not counterfeit passports, though. That would be a crime.

One can acquire Turkish citizenship in exchange for money, through completely official channels. This is regulated through the citizenship law No. 5901, Art. 12. In order to become a Turk, you must demonstrate that you have either bought Turkish real estate for at least $400,000; created at least fifty jobs; or put at least a half a million into investments in Turkish companies, deposits in Turkish banks, or purchases of Turkish government bonds and securities. When one is able to buy citizenship according to these sorts of defined criteria, it is called a “passport program.” In Turkey, a country suffering under the devaluation of its currency, this program is funneling billions of hard dollars into state coffers.

You can only get a passport from a state, therefore passport sellers are always states. Formally, Turkey calls a purchase an “application.” Anyone can apply, except for people from enemy neighboring countries like Armenia. You don’t even have to submit a police certificate of conduct. Officially, the Turkish interior ministry handles the vetting of candidates. Before the Russians came, since 2018, around 20,000 Iranians, Iraqis, Yemenis, and Afghans – who often cannot get so much as entry permits or visas to other countries – had procured Turkish passports. For some of them, Turkish citizenship is a stepping stone to further travel into the US, the EU, or Switzerland.

When the full-scale war in Ukraine started, demand increased so sharply that in May 2022, Turkey raised the price – by a healthy sixty percent. Thereafter, citizenship via real estate purchase cost $400,000 US. Before, you’d only had to invest $250,000.

Turkey does not publish any numbers from this program, or the names of its customers. One indicator to follow, however, is real estate purchases. Thanks to the Turkish statistics office, we know that in February 2022 the number of Russians buying real estate was already double that of the same month the year before. In June 2022, it was six times the number in June of the previous year. Between January and July 2022, almost seven thousand Russians bought real estate in Turkey.

Both countries allow dual citizenship. So if an EU travel ban for Russians were to be declared, these newly minted Turks would still be able to travel to the EU, and would still be able to transfer money internationally – which is difficult for Russians today as a result of sanctions. In addition, if you only have a Russian passport, you are at Putin’s mercy. Passports, formally, are state property; this is printed on almost every one of them. Putin can revoke any Russian passport at any time.

This is why the superyachts of Russian billionaires are clogging Turkish ports. And Russia’s internet giant Mail.ru (known as VK) plans to resettle two thousand software developers in Turkey. The country is becoming a Russian outpost.

The fact that Turkey offers citizenship for money at all is thanks in large part to Christian Kälin.

4. Passports, from A as in Antigua to T as in Turkey

A gray, five-story, turn-of-the-century building on Klosbachstrasse in the posh Hottingen neighborhood of Zurich – here, on the ground floor, I find Kälin’s office. The company is called Henley & Partners; he inherited the English name when, together with his family, he bought out the British-American firm. Today, Kälin is the chairman of the board.

At our first meeting, a receptionist leads me into a bright conference room. She serves me coffee in a porcelain cup, a piece of chocolate to go with it. Books by Kälin line a wooden shelf; brochures are laid out for perusal. At the window, there is a row of exotic flags, like in a consulate. Henley & Partners has roughly three dozen offices around the world. The one in Moscow closed shortly after our conversation.

On their website, Henley & Partners advertises eleven citizenships, listed alphabetically from A as in Antigua to T as in Turkey. Furthermore, there are currently twenty-five so-called “golden visas,” residence permits in exchange for “investments,” for countries like Portugal, for example – or Switzerland. It is emphatically not the case, however, that one can buy Swiss citizenship, Kälin explains to me over tea.

Many Swiss cantons will grant wealthy applicants temporary residence: the B-Permit. This typically entails a flat tax – in other words, a fixed yearly fee starting at about 150,000 Swiss francs. Applications must be sent in advance for review by the federal government, who can assert veto power. The federal government can additionally have the submitted dossier inspected by federal police, and decides each case individually. The legal basis for this is Art. 30 in the Foreign Nationals and Integration Law, which permits naturalization for reasons of “significant public interest,” which category includes “substantial cantonal financial interests.” Since 2008, 5,094 people have received residence permits for reasons of public interest, according to the State Secretariat for Migration (SEM). Names are not public. Some applications have been turned down. The SEM will not provide any further details.

Kälin’s company is the global market leader in “citizenship by investment,” I had read on his website. I had also watched a video in which Kälin declared, “Henley & Partners is the company that built this industry.”

“This industry—is it passport-dealing?” I ask.

“No, no.” He shakes his head vehemently. “Buying and selling passports does occur in illegal markets, but we have absolutely nothing to do with that.” What he does is completely legal, he says. “The right way to say it is citizenship by investment, citizenship program, granting of citizenship through investment, or if need be, passport program or passports by investment.” I should not use the “wrong terms,” he admonishes me. “Henley & Partners does not ‘trade’ or ‘deal’ in passports. I explain that to all my people over and over, and also to governments, whenever it passes their lips.”

When I want to know more, Kälin hesitates. He has already had bad press, he says. He is referring to the reports of “election influence,” the innuendos in connection with the murder of Maltese journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, and the reports of suspected criminals, politicians, and oligarchs being among those for whom Henley & Partners has apparently procured passports. The media, the EU, the OECD – they have treated him unfairly, says Kälin. He has helped tens of thousands of people into better lives, he says. After a sip of tea he begins to recount how it all started.

5. St. Kitts 2006: Passports off a conveyor belt

In 2006, Christian Kälin, then thirty-four, traveled to St. Kitts and Nevis.

The island pair belongs to the strip of Caribbean islands that stretches from Venezuela to Cuba. The islands were facing great difficulty in 2006. St. Kitts and Nevis had, until just before then, mainly subsisted off its sugar cane plantations. But in 2005, the EU had altered its import conditions for sugar. The economy was running aground.

Kälin was already working for the small trust corporation Henley & Partners, which specialized in international projects and migration law. He had visited the country a couple of times before; this time, though, he had a proposal for the premier in his pocket.

The Swiss man was well acquainted with the wishes of wealthy customers. He had interned at a Zurich private bank, which had later been bought by Coutts & Co – who, for their part, were wracked by scandal in 2014 as a result of offshore trusts in the Cayman Islands, among other places. In the mid-nineties, when he was in law school, Kälin was hired on at a then-still-small Zurich trust corporation that specialized in citizenship law: Henley & Partners. Many customers sought not only tax havens for companies – they wanted to resettle to, buy real estate in, or make investments in foreign markets. For which they would need residence papers. This became Kälin’s specialty.

Net-positive-immigration countries like Canada or the US have long been offering investors residence papers for purchase. Golden visas like the EB-5 in the US. If you’ve invested at least $800,000 in US companies, you can attain legal long-term residence. Since 2008, this arrangement has brought $37 billion into the United States. Donald Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, for example, has financed real estate projects with this money.

But it was a small mountainous country in the heart of Europe that fascinated Kälin the most: Austria. There, since 1985, the citizenship law has allowed that naturalization be granted for “exceptional achievements of special interest to the republic.” An Austrian passport can be obtained in exchange for millions in investments or social philanthropy. This is a constitutional-level law, explains the Viennese attorney Stefan Pacher, but transparent criteria are lacking for the process of acquiring citizenship. All ministers of the entire federal government get together to decide on these citizenship applications, every six months. So these are the people you have to be able to get a hold of, and persuade. There is a lot of room for discretion. What that meant for Kälin, besides potential paydays from his clients, was cultivating contacts, arranging meetings and gatherings, furnishing mass-tailored legal arguments.

Kälin saw how labor-intensive this was. On the other hand, every successfully brokered citizenship brought in hundreds of thousands of francs in fees.

Besides Austria – and only specialists like him knew about that – one could only legally purchase citizenship in St. Kitts and Nevis, or Dominica, also an island nation. Both island passports had a bad reputation. But then, fate played into Kälin’s hands.

Canada let its investor visa rule, until then the world’s most favored, expire. The waiting list for the Federal Investor Immigration Program had gotten so long that it was already taking as long as a regular citizenship process. So the demand for a comparable visa – or even passport – exploded. And when St. Kitts and Nevis suddenly lost sugar as its main source of income in 2005, the island nation was facing catastrophe. Kälin saw his chance.

So there he was, sitting in the tiny office of premier Denzil Douglas on the top floor of government headquarters in the capital city, Basseterre, explaining how he could make St. Kitts and Nevis a lot of money: by bringing in investors who were interested in attaining citizenship and were ready to make the necessary investments. In a big way.

This sounded like a strange proposal. The Caribbean island already had a passport program. However, in 2005 they had sold a grand total of six citizenships. It bears mentioning that the St. Kittians basically invented “passport-dealing.” The story is hair-raising – and was the main reason almost no one wanted their passport. The purchase of citizenship in St. Kitts and Nevis was inaugurated when, in the island nation’s year of independence, 1983, a French middleman for the Medellín cartel had attempted to come into possession of passports there. He needed new identities for his clients. This inspired a resourceful politician to take initiative: the following year, parliament issued a law allowing the purchase of citizenship – for $50,000 US and a service fee.

Nonetheless, when Kälin started out in St. Kitts, it was complicated to purchase such an island citizenship. It could take months or years, depending on which minister you ended up with. No one held legal responsibility.

Now, this blond newcomer was explaining to the premier that he wanted to “scale up,” to make the purchase of citizenship into an industry. He had a vision: something like the Austrian passport – as reputable, but much cheaper. Therefore in greater volume, as Canada had done. His plan was clear: passports off a conveyor belt—good ones, too!

Kälin explained to the premier that he would raise the price, or, the “investment criteria.” He would also more strictly vet those who would receive passports. No criminals. This would make the product attractive. In turn, he would make it easier to access. And he would promote the hell out of St. Kitts and Nevis and its passport.

With the revenue from this, the leader would be able to rescue his country.

Premier Douglas was interested. But, he responded, he had no budget for such a project.

Kälin had accounted for this, too. Everything would be free of cost. Henley & Partners would finance the work on the front end, at their own risk, if a $20,000 premium is paid for every case they broker successfully. St. Kitts and Nevis would be giving Henley & Partners monopoly control of marketing and promotion, and would let Henley & Partners design the process – in other words, the legal provisions and procedures for the purchase of citizenship.

Douglas agreed.

Kälin knew exactly who his clients would be. On the one hand, there were traditionally many Americans and Brits who bought vacation homes on the islands. They surely wouldn’t turn down a passport as a bonus to buying a house. The others were a new target audience, however.

Globalization was firing on all cylinders. World trade meant offshoring: the export of production processes away from the expensive West into Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, and South America. A new class of wealthy businesspeople was emerging. The number of rich people in so-called developing countries was growing rapidly, and still is today. There are 62 million people worldwide who have one million dollars or more to their name. Over eight million of them are from Africa, the Middle East, and Asia.

At home, they lead first-class lives – but their passport is often a liability. If you’re from Bangladesh or Nigeria, for example, and you want to go to New York for shopping or business, you have to wait months for a visa. All of these people could really use a better passport. It’s not about moving to St. Kitts. They just want the passport. Kälin was on the scent of millions of clients. He called them: Global Citizens.

6. The St. Kitts Model: Citizenship for $250K, plus additional fees

“We did it all in St. Kitts,” Kälin effuses, still pleased with himself. He was able to devise rules entirely in the interests of his clients. For the first time in history, the market determined who became a citizen. It was the birth of an entire sector, and a template for how Kälin would soon break into the European Union.

Here in St. Kitts, Kälin created the blueprint for the way almost all “passport programs” work today. From the legal provisions to the administrative procedures all the way down to logos, websites, brochures – even job postings.

As for the price of a passport – or, more accurately, of citizenship – Kälin upped the ante: a quarter million, plus a “fee.” In order to acquire a passport for themselves and up to three family members (so-called financial dependents), a client could choose: either invest $250,000 in real estate on the island, or donate $150,000 to a money pot of Kälin’s devising: the government-established Sugar Industry Diversification Fund (SIDF).

If you donated instead of buying real estate, you also paid significantly less in fees: only $7,500 instead of $50,000. The incentive was clear. The SIDF was just what Kälin had promised prime minister Denzil Douglas: free money with which to shore up the staggering economy, formally disbursed as independent grants, but in reality a political pork barrel for the premier. The rules were always getting tweaked. Soon the minimum investment in real estate rose to $400,000, which unleashed a boom in luxury properties, and soon after the SIDF was jumping into lots of different activities: from financing of social housing and investments all the way to private loans for individual people.

Anyone could apply. You need not move to the country or even appear in person a single time; your application would be reviewed according to established, set rules. You would just need to undergo some so-called due diligence, in order to rule out undesirable clients who would drive down the value of a St. Kitts and Nevis passport. If criminals start using a certain passport, other countries will become wary and limit admissions for those passport holders.

Before, recalled Kälin, St. Kitts and Nevis might have looked up a local criminal history, or at most scanned Interpol lists. Almost no one was searching other databases, much less contacting the international money-laundering watchdog authorities at the FIU [Financial Intelligence Units].

Henley & Partners, in contrast, created numerous forms where clients had to make disclosures about, among other things, the sources of the money they were using to pay for the passport. To administer the process, Henley & Partners created its own official authority in St. Kitts and Nevis: the Citizenship by Investment Unit (CIU), which reported directly to the premier. This was the first time a state had had a central facility devoted to serving passport customers. And there were even control mechanisms: the state auditor general supervised the CIU, and the SIDF had PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), a global financial firm, looking over its shoulder.

Whoever paid and passed verification received citizenship – and therefore a passport. Nonetheless, when he was starting out in St. Kitts and Nevis, it looked like Kälin’s passport program might flop. In 2006, St. Kitts and Nevis sold only nineteen citizenships. “Saint what?” everyone asked when the Zuricher presented his Caribbean passport in Hong Kong. He and his team went on a traveling roadshow for three years pushing their “product.” Sales grew, but slowly. In 2007 it was seventy-five passports. In 2008, two hundred and two.

Throughout this whole experiment, however, Kälin was moonlighting in a different venue entirely, working towards his ultimate breakthrough: Brussels.

7. Off to Europe

For a while already, St. Kitts and Nevis had been negotiating with the EU over waiving visa requirements for its citizens. Christian Kälin was an official member of the bargaining delegation. Premier Douglas had named him “special envoy for bilateral agreements” as well as honorary general consul for Switzerland.

No country is required to grant entry to citizens of another country. However, when it appears to be mutually beneficial, countries enter into agreements that allow each others’ citizens free admittance. This is called a visa waiver. Everyone else must apply for entry, and the certificate of a successful application is called a visa. The scope of review for applications varies. Powerful countries regularly deny the visa applications of persons from “third countries” that are thought to be sources of elevated migration pressure (which means almost all the poorer countries in the world), with the pretext that these persons’ return to their countries of origin cannot be ensured, as lawyer and professor of migration law Marc Spescha explains. A passport with a visa waiver is therefore like a key to other countries. The more visa waivers a passport has, the more useful it is for travel – and in Kälin’s logic, the more valuable it becomes.

Swiss people almost never encounter visa requirements. They have visa-free access to 186 countries. In the year 2006, St. Kitts and Nevis had just sixty-two visa waivers. Unrestricted travel to the EU would turn the St. Kitts and Nevis passport to gold for Kälin.

On 30 June 2009, the EU and St. Kitts signed an agreement. From then on, anyone with a passport from St. Kitts could travel visa-free to the EU and could remain there for up to three months every half year. In one stroke, the passport became much more sought-after. Soon the island nation was selling over two thousand citizenships annually.

Since then, the passport program has doubled the nation’s population on paper, former government minister Dwyer Astaphan estimated in early 2021. Many applications included family members and other additional persons. A real estate boom commenced, even though only a tiny fraction of passport recipients actually resettled. Luxurious buildings – often hotels – began sprouting up on the islands, since the required investment stood at $400,000. Instead of becoming impoverished like Haiti, the island nation became a luxury destination.

State revenues exploded. Soon the passport program was the largest single source of income for the country, accounting for more than a quarter of the yearly economic product and forty percent of revenue. St. Kitts and Nevis no longer made its living from sugar cane, but from passports. Kälin’s company, Henley & Partners, was earning around forty million dollars a year.

“It was like we’d struck oil! And we turned the country around,” gushes Kälin. Soon neighboring islands were calling him. “I know everyone in the Caribbean,” he says. And while money was already flowing like a geyser, the next collapse played into Kälin’s hands too: as a result of the 2008 global financial crisis, state governments would all be in search of new sources of revenue. Along the way, they would stumble upon Kälin’s business model.

8. Kälin, savior of state economies

From 2009 on, Kälin began to develop passport and visa programs worldwide, going almost entirely unnoticed by the public. Henley & Partners offered governments everything: from basic consultations with authorities to the development of legal frameworks all the way to a full service plan under which Kälin’s company would also take care of all the marketing.

In 2009, his firm developed a golden visa for investors in Latvia—since then it has brought over twenty thousand people into the country. Eighty percent of them Russian. The following year, he collaborated on a reform to the investor visa program in Great Britain, which allowed for permanent residence permits. In this case, the more you invested, the more quickly you could get your documents. For two million pounds, it would be a five year process. For ten million and up, only two years. Over twelve thousand visas were issued; at least seventeen billion pounds flowed into the country; over twenty percent of the so-called Tier-1 visas went to Russian millionaires, who bought up so much real estate in central London that some neighborhoods got nicknamed “Londongrad.” In 2010, Henley & Partners started a passport program in Montenegro that promised a passport for 450,000 euros. Montenegro’s candidacy for accession to the EU made their passport more valuable. Applicants today are mostly Chinese and Russian.

Henley & Partners had now grown from a mere company to a full-blown Operation. An administrative headquarters was established on the tax haven Isle of Jersey (it has since been shuttered); in Lisbon, a central office was established for the coordination of negotiations with governments and politicians worldwide. The seat of their parent company would later be established in Dubai. Amid this success, Kälin pulled out of direct contact with individual clients. He withdrew to an estate on Nevis with spacious grounds, and there set about writing a doctoral thesis about his innovation: “Ius Doni,” or Law of the Gift.

9. Malta 2013: The big push

Malta is a small archipelago between Sicily and Libya, the tenth smallest country in the world. With 516,000 residents, it is densely populated, and given its lack of natural resources it is dependent on other sources of income. It was a British colony until 1964. Today, Malta is the smallest EU country. Anyone with a Maltese passport is also an EU citizen.

Kälin had been coming here for years. The finance minister at the time, Tonio Fenech, had been a strong advocate for him, Kälin told me (Fenech would go on to author the preface to one of Kälin’s numerous manuals). The long-standing government of the Nationalist Party would have liked to introduce a passport program, but only had a one-seat majority in parliament – 35 to 34. Too narrow to pass tricky laws like the sale of Maltese citizenship.

So Kälin also turned to the opposition. He always talks to all sides, he explains to me. “One group is in power today, the other tomorrow.” In 2011 he received an invitation to the headquarters of the opposition party Partit Laborista – the social democratic workers party – and met a handful of young politicians, among them Keith Schembri, the future chief of staff to the head of government. For Kälin it was a meeting much like any other. There was an exchange of business cards, he pitched his company’s services. His offer was the same as in St. Kitts: if they instituted his passport program, Malta would bring in a lot of money. Hundreds of millions of euros.

In March 2013, the social democrat Joseph Muscat came to power with an absolute majority and announced a draft passport program as one of his first economic measures. On 4 October 2013 Muscat introduced the plan – designed, implemented, and brought to market by Henley & Partners, who would also be overseeing the passport program’s worldwide promotion.

An EU passport in his catalog: this was a coup for Kälin. Soon his company would be processing forty percent of Malta’s citizenship applications, and their largest office would be in Malta. To this day, Kälin regards Malta’s Individual Investor Program as his masterpiece. From then on, he would wear EU flag pins in public and in client meetings, and advertised the program as “the only passport program recognized by the EU.” Images of the EU parliament building appeared in his promotional videos.

Kälin’s team drafted laws, devised rules for the vetting of applicants, and created, just as in St. Kitts, a state endowment fund that would collect seventy percent of all revenue and disburse it transparently. Under opposition pressure, an upper limit was set of 1,800 passports over a pilot period of several years. As remuneration, Kälin’s company would get four percent on every successful application. With a minimum investment of 650,000 euros, this meant 26,000 euros per citizenship for Henley & Partners. Additionally, Kälin would earn client fees.

The contract between Malta and Henley & Partners had initially been secret, which appalled critics. In the meantime, much has become more visible; since 2020 a revised passport program has been in force. Here is the exact process for purchasing citizenship:

Extended presence on the island is not necessary; two short appointments for submitting the application and picking up the passport are sufficient. A house or apartment counts as “presence” in the country.

Of course, a sheaf of documents is requested. It is first reviewed by an agency such as Henley & Partners. These agencies use services like World Check, a database where one can look up whether a person is on sanctions lists, has dubious relationships, or presents a political risk.

If a person is classified as risky by World Check, the diligent passport brokers will retain private investigators or financial detective agencies to evaluate whether they or their clients should accept them. There follows an additional check in police databases like Interpol, Europol, and the FIU. Alongside this, the Maltese government will retain two additional independent private global detective agencies who will each scrutinize and document the background of the applicant. Applicants who need Schengen visas – so, the vast majority of them – must also undergo the normal Schengen visa process.

During the application process, extensive personal data will thus be collected. Kälin estimates his company has arranged citizenship for tens of thousands of uberwealthy people. And every one of his clients has had to open their entire life up to scrutiny: the sources of all their wealth, and any potentially dirty laundry. No one knows more about wealthy people, he declares to me one day. “We know their relatives, their banks, their girlfriends and second wives, even entire second families.”

As a third step, the Community Malta Agency checks the correctness and accuracy of the applications – most importantly, the sources of the applicant’s wealth and assets.

Finally, the board of Community Malta Agency must recommend candidates for citizenship to a minister. Whoever is accepted must pay into the state endowment fund. Newly naturalized Maltese citizens will be announced by name in the official government newsletter, Gazetta.

This kind of transparency has consequences, as it scares off clients from states that forbid dual citizenship, like Saudi Arabia or China. Between 2014 and 2020, twenty-three percent of all applicants were refused. This is the highest refusal rate of any such passport program. Admittedly, only very few countries publish the names of their investor-citizens or their refusal rates. Nonetheless, passport brokers regard Malta as the strictest and most transparent passport program. Critics see it as a gateway for corrupt elites.

Indeed: as soon as they pass the first stage of the exam, applicants receive a residence permit which grants entry to the EU. While the St. Kitts passport was marketed to moneyed elites from developing countries, the Maltese passport, which is three times as expensive, is an offer for people with an average of over thirty million dollars on hand – so-called ultra-high-net-worth individuals. It is attractive for people from countries like Russia or Saudi Arabia, because it offers visa-free entry to over 185 states, right of permanent residence in the entire EU, and temporary residence in Switzerland. With this passport, you can easily travel to New York, St. Moritz, or London – even live there – and open a bank account in the EU.

How much does EU citizenship cost today, for one family of four? I’ll have Henley & Partners provide us with a quote: Malta Express – with the shortened waiting period of twelve months instead of thirty-six – comes in at 1,122,999 euros, including fees of 160,000 euros. For individuals, the starting price is 750,000 euros.

This citizenship was a big hit in the world of the wealthy. “We completely transformed Malta, we brought in so much money there,” says Kälin proudly. But in Malta he had actually hit something of a wasp’s nest.

10. The explosion

Luck had been at Christian Kälin’s side for a long while. Now, at the peak of his success, it turned away from him. He had encountered an unexpected opponent in Malta: Daphne Caruana Galizia, who would later be killed in a targeted attack.

The hunch this journalist was pursuing on her blog Running Commentary was just outrageous enough that at first she wasn’t taken very seriously by parts of the establishment media: her theory was that the government was trying to turn Malta into a mafia state.

All of Malta knew “Daphne,” as they call her here. In a country with half a million residents, she had, on some days, as many as four hundred thousand visitors to her blog. The trained archaeologist and mother of three was by herself the largest independent media source in the nation.

She held from the start that Malta’s “sale of citizenship,” as she called it, was illegal, and moreover that it was defrauding voters. She hadn’t liked Henley & Partners when they first showed up in Malta in 2013. Over the next few years, she would research and publish dozens of critical articles. She warned of the entire country being sold off to dubious elites – and of corruption. She revealed that hundreds of millions in the revenue Malta had taken in since 2016 had never been deposited in the endowment fund.

It was the network Kälin was building within the government that bothered her the most. Because of his contacts, he was more than just a passport broker. On her blog, she documented how Kälin operated. Kälin had contractually obligated the Maltese government to participate in his marketing events, which Henley & Partners had conceived as “conferences.” The first time Maltese premier Joseph Muscat attended one of these events in 2013, Kälin introduced him to a very special client: Ali Sadr Hashemi Nejad, known as Ali Sadr, son of the richest Iranian businessman at the time. Thanks to his St. Kitts citizenship, Ali Sadr could engage in international commerce despite sanctions on Iran. Soon after meeting Muscat, Sadr opened a bank in Malta: the Pilatus Bank.

Caruana Galizia started to look into conspicuous Pilatus Bank clients, and discovered accounts belonging to the government-enmeshed company 17 Black. Company owner Yorgen Fenech is now on trial for allegedly contracting to have her murdered.

On a weekly basis, and sometimes daily, Caruana Galizia published her most recent findings, as well as pure speculation, some of which was wrong. Kälin feared for his reputation and repeatedly demanded she delete certain posts. Then, Henley & Partners hired the London law office Mishcon de Reya, who are known for intimidating journalists with threats of litigation. Caruana Galizia responded with leaked e-mails in which Kälin and the Maltese head of government along with his chief of staff reached agreements on legal action against her.

In May 2017, Kälin attempted to win her over in person. He told me that she showed herself to be reasonable and deleted some posts, but that another injunction from the London lawyers had set her off and she went back on the attack. How much the two actually agreed upon can no longer be reconstructed today. On her blog, Caruana Galizia writes that she told Kälin he couldn’t behave in Malta the way he had in St. Kitts – like a colonial power.

On 6 October 2017 she wrote her final blog entry on the passport program. On 16 October she was killed by a car bomb.

With a thunder strike, the discreet Passport King and his business were suddenly in the spotlight. Reporters from all over the world showed up in Malta. The EU announced the Daphne Journalism Prize; the Daphne Research Foundation was set up. The incident unleashed an avalanche of revelations.

11. Passport brokers fall on harder times

In 2018 an internal database from Henley & Partners was leaked. It quickly became clear that there had already been numerous scandals that only a precious few in Europe had ever heard anything about.

For example, in 2011 Henley & Partners had assisted the Nigerian financial fraudster Oluwaseun Ogunbambo in his attempt to attain citizenship in St. Kitts and Nevis. This was not Kälin’s intention. Unscrupulous clients used a kind of loophole in Henley’s security checks, in which they would send unblemished relatives in their stead, having themselves listed only as “financial dependents” and therefore avoiding any scrutiny.

And in 2014, Fincen, the US authority overseeing financial crimes, published a warning about Caribbean passport programs. Above all they criticized Kälin’s practice, introduced during his collaboration with St. Kitts and Nevis, of not printing the birthplace of new citizens on the passports they were sold. As a consequence, islanders had had to recall five thousand passports.

In the Caribbean, where Kälin had established a passport program for numerous island nations in the early 2010s, it was evident that he had really earned the magisterial title “Passport King” by how many liberties he took. At the outset of the decade, for example, Kälin had helped his friend Patrick Liotard-Vogt get a passport from St. Kitts and Nevis, advocating for him with personal recommendation letters. Kälin had previously advised the Swiss jet-setter on how he could re-brand the social network for rich people he had bought – ASmallWorld – and relocate it to Switzerland. Soon he was assisting him with investments in St. Kitts, such as hotel developments. Just an example of how Kälin used his network of clients.

Kälin even intervened in election campaigns in the Caribbean, as reported by Fast Company, the Guardian, and the Tages-Anzeiger. For at least two different candidates’ campaigns, in the island nations of St. Vincent and St. Kitts and Nevis, Kälin had arranged contacts to potential investors for election campaign manager and Cambridge Analytica founder Alexander Nix, who was active on the islands and would later become infamous for his collaboration with Donald Trump. When asked about this, Kälin says that the passport program had never been under threat and that he had had good relationships with the opposition as well.

In Malta too, the press found questionable new citizens, mostly Russians with a lot of money and influence such as the former CEO of Russia’s largest investment bank, Alfa; the founder of the tech giant Yandex; or the CEO of the industry-leading alcohol distributor Beluga Group. Large sections of the Russian elite had bought into the EU – opponents as well as allies of Putin. Early on, Russians had already made up forty percent of all passport customers in Malta. Two Saudi business families alone had had sixty-two passports brokered – even though Saudi Arabia forbids dual citizenship. A member of the Saudi royal family had even convinced Malta’s head of state not to publish his name as required. In late 2019, Muscat’s government fell, under bribery accusations and the intimate ties chief-of-staff Keith Schembri had to 17 Black, the financial vehicle uncovered by Caruana Galizia, as well as questions around Schembri’s role in connection to Daphne Caruana Galizia’s murder.

Every once in a while, says Kälin, one might accidentally work for “bad people.” But that’s just how it is. Like with banks. For every thousand clients, there is bound to be a handful of rotten eggs. Kälin was never responsible for citizenship decisions. In precise terms, Henley & Partners is only a broker. “Consultants consult, states decide,” says Kälin.

If a state should ever earn the reputation of harboring suspect characters, it has consequences for all citizens of that state. Travel becomes significantly more difficult, because visa waivers get canceled. International money transfers become more difficult if institutions like the OECD or the International Monetary Fund begin to suspect money laundering and put countries on a gray or black list. Financial flows are constrained, and payments coming from the country in question get much more heavily scrutinized, or even blocked. In 2021, Malta landed temporarily on a “gray list.”

12. The EU says No

Critics in the EU parliament were getting more fired up about the increasingly obvious extent of the problems that this business in citizenships brought with it.

From the start of the Maltese passport program, resistance to it had been forming in the EU, which at first remained ineffectual.

Their point of departure was clear. For decades the EU had been promoting citizenship in the Union. It is, so to speak, an award to citizens, a kind of upgrade from the passport of any member country: freedom of movement, suffrage rights, freedom of residence, and a discrimination ban. Then came the passport brokers, offering all this on their websites for around a million euros.

In January 2014, just as the passport program in Malta was getting started, then-vice president of the European Commission Viviane Reding declared: “Citizenship will not be put up for sale.” You cannot put a price tag on EU citizenship. The EU parliament passed a resolution, with extraordinary unity – over eighty-eight percent – against golden passports, in which it was pronounced that citizenship should only be available to those with a genuine connection to a country.

This begs the question of what a “genuine connection” is. This has long been disputed in constitutional law.

States decide who may belong – this is a basic part of sovereignty. Only the European Commission can compel EU states to do anything, formally speaking. But the European Commission is comprised of representatives from member governments. If they were to attempt to put limits on their own naturalization processes, they would be undermining themselves. It’s a quandary.

This set off a dispute between the EU parliament and the European Commission. The internal gridlock revealed the lack of democracy at the heart of the EU: the people’s representative, parliament, is not the sovereign; it could pass resolutions, but not laws. In March 2019, after numerous other fact-finding probes, the European Commission decided to deploy yet another team of experts to look into the risks of investor citizenships.

It could probably have gone on this way forever, if journalists from Al-Jazeera hadn’t uncovered how corruption-prone the flourishing EU passport program was in Cyprus. Kälin hadn’t had a hand in creating this one, although his company was brokering citizenships there too. At 2.15 million euros per citizenship, Cyprus was much more expensive than Malta, but a favorite of Chinese and Russians. Nearly seven thousand citizenships had been issued – four times as many as in Malta. In the EU nation of Cyprus there emerged entire Russian districts: Limassol turned into Limassolgrad. And just as in St. Kitts, this investor migration threw up luxury hotels everywhere. This cashflow made up around 4.5% of the gross national product of the island.

Al-Jazeera filmed undercover as Cypriot passport brokers, real estate moguls, and the speaker of parliament accepted bribes. An investigative commission later found processing errors in over half of all the naturalizations they examined. Dozens of passports and their corresponding citizenships would later be revoked.

In September 2020, president of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen proclaimed: “European values are not for sale.” A “treaty violation proceeding” would be initiated against Cyprus and Malta. The Cypriots put their program on ice, and stopped admitting new customers.

In 2020 and 2021, the pandemic shut down air travel worldwide, as well as the operations of many state administrations. Passport brokers could no longer deliver. On the one hand, customers were lining up to wait; on the other hand, Beijing’s Zero-COVID policy and the intensifying controls it imposed on its citizens basically extinguished demand in China. Kälin’s business dropped by seventy percent, he told me.

On 24 February 2022, Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine. On 26 February, the White House commanded, in a joint declaration with France, Germany, Italy, Great Britain, Canada, and the European Commission, that no further citizenships be sold to Russians. Countries that offered such citizenships came under scrutiny. In June, Switzerland canceled its visa waiver for all citizens of Vanuatu, which had begun selling its passport in 2015. The EU had already taken this step in March. Also in March, Bulgaria decided to shelve its passport program. Austria succeeded in staying out of the discussion, because it had never formalized its passport program. Now only Malta was left.

On 10 May 2022, Ukrainian president Zelenskyy pleaded in a video statement for the Maltese parliament to revoke Russians’ golden passports and seize all their assets. Malta decided to suspend granting citizenship to Russians and Belorussians (which redirected the flow of Russians to Turkey), but refused to give up the passport program entirely. On 29 September, the European Commission ultimately decided to charge Malta before the European Court of Justice. Eight years after Kälin’s greatest success, it appeared the end was near.

Or was it?

13. One morning at WEF 2022

One morning in May 2022, I’m on my way to Davos, for the World Economic Forum. Kälin had invited me. He wants to show me that his business in citizenships is not on the brink of collapse, but quite the opposite: it’s on the verge of a breakthrough. So he’s bringing me along to secret negotiations. I would have to sign a non-disclosure agreement beforehand. I am not allowed to disclose who he met with over these two days.

The meeting spot in Davos is the Hard Rock Hotel, where Kälin has a round table in the restaurant reserved for several days running. As always, he has a pin on his suit coat. “We used to have a booth at WEF,” he says. “Then I realized that we didn’t need it. Governments were coming to me.” In London he would always receive government representatives at the same hotel; in Zurich, premiers would come to meet him at a billiards club. “We’re a relatively small company, with barely four hundred employees, but we punch above our weight.”

And indeed, government representatives arrive, one after the other. Roughly every hour and a half, a new table is set. Coffee, avocado salad, burgers. To start, Christian Kälin always slides a copy of his self-published promo-book, Residence & Citizenship Programs: Government Advisory, across the table. It is littered with portraits of grinning clients and government officials. The conversation is always the same: the premiers, chiefs of staff, or foreign ministers of smaller nations need money for their state coffers.

Kälin plays with numbers. Six hundred to seven hundred passports a year, he reckons, should earn them a hundred and fifty million in direct investments, and three hundred million in the real estate market. An especially well-informed prospective client asks: North Macedonia also offers citizenship – who ends up there? Mostly Chinese and other Asians, replies an H&P colleague, but it’s a new program and they don’t have numbers yet. Nods around the table. No one expresses any moral concerns, but every government is worried about ending up on a gray list or getting kicked out of international treaties. “The EU is freaking out over ten problem cases that slipped past due diligence,” says Kälin, “while they’re letting in hundreds of thousands of migrants unchecked, without batting an eye.”

Kälin is in his element; he has an answer for everything. He advises one interlocutor to rename their passport program and sell it anew as an initiative for attracting tech talent. In another case he offers his analysis on whether a critic who works at the OECD presents a serious threat. Kälin knows his opponents. He has ten people flying the globe all year, nurturing relationships with government officials.

Once the last foreign minister of the day has left, he snaps his fingers with satisfaction. “We’ve been lying in wait for that country for twenty years, like a tiger stalking an antelope.”

Suddenly, in the afternoon on the second day, just after a rather disappointing meeting in which he had gotten the brush-off from a prime minister, he jumps up with delight. An invitation from a powerful country. This time we go to them, hustling down Dorfstrasse in Davos, and enter a rented storefront property, where we are invited into a back room.

“Bring me the billionaires!” shouts the minister of an EU country as Kälin steps into the back room. “I am your project’s biggest fan, I am really your program’s biggest fan, and we absolutely need it over here.”

Kälin smiles.

“But the problem,” proceeds the minister, “is our head of state. And the real problem is the Cypriots.”

What he means by this is the situation that Al-Jazeera had filmed, showing how corrupt the Cypriot passport program had been.

Everyone takes a seat. The minister glances around mirthfully: “Oh, when everyone saw what they were doing! They were really telling people, they said to criminals, ‘Just change your name!’ On camera!”

A burst of laughter erupts among the minister’s people. Now we just have to wait and see whether the Cypriots have to pay a penalty, and how high, says the minister.

“They won’t have to…” starts Kälin knowingly. The minister cuts him off: “You know what I really think? We can’t build cars, but we can offer a good quality of life. Bring us a couple billionaires, please. Move them right into our villas.”

Kälin wants to get on with it. But as he starts to roll out a plan for the implementation of his new passport program, the minister waves it off: “That doesn’t help with the Cyprus problem.”

Kälin leans back. “We’re in conversation with two other European countries.”

The minister looks up. “If Austria offers it, and we do, and two others, that changes everything!”

“Exactly,” says Kälin. “Then the EU can’t do anything but accept it.”

14. Kälin’s connection in the European Commission

Just before the EU’s decision to bring suit against Malta, I ask Kälin how dangerous the European Commission could be to his business. They had just served Malta and Cyprus with so-called Reasoned Opinions – the final preliminary step before a charge.

Kälin downplays it as usual. I remember the list of his legal experts that he had sent me. Among these is his friend Dmitry Kochenov, with whom Kälin had already connected me at a conference in Brussels. Kochenov looks like a red-haired Einstein and likes to turn out in a double-breasted suit with a brightly colored bow tie. He is known as a brilliant European constitutional law scholar – and he hates passports. He gives speeches and publishes books in which he declares citizenship as such to be racist. It combines blood and soil, he argues, since citizenship is mostly passed down via parents, i.e. bloodlines.

Nothing is a greater determinant of our material well-being than the citizenship we are born into, he explained to me when I met him between sessions of a passport brokers summit, where he had given a fiery speech. Kochenov is the patron saint of passport brokers. They love him for explaining so well that their business model is good. Citizenship is, to him, like a forced marriage, a form of slavery. Any niche that offers an escape from this bondage is positive.

Kälin had first met Kochenov in 2011, in the lounge at Zurich airport. Both had been on their way to Malta. The government there wanted to consult with Kochenov about whether their planned investor passport program was legal. Kochenov found that yes, it was. Since then, the two have been friends. In 2020, they published an index that they had developed together, rating the value of citizenships: the “Quality of Nationality Index.” The QNI measures factors like freedom of movement and market freedom, and synthesizes the results into a global ranking system.

In 2021, Kochenov was forced out of his university in Holland due to criticism over the work he did on the Maltese passport program. Now he teaches at Central European University in Vienna.

Kochenov explains to me why the European Commission doesn’t stand much of a chance at being able to limit member countries’ citizenship sales. His argument: the EU consists of sovereign states. To strip these states of their ability to “form” their own population denies them their statehood and the essence of their sovereignty. In sum: without sovereign states, there can be no federation among sovereign states, and therefore no EU.

It is this loophole in international constitutional law that makes the business in citizenships viable.

But Kochenov has even more to offer. “A good friend of mine has worked on this topic at the Commission,” he texts me. “In case you’re interested in an insider perspective, I can connect you.”

So Kälin’s advisor Kochenov, then, has a direct relationship to the top regulator of the sector: the legal counsel to the general director of the European Commission.

Of course I am interested.

The next day I am speaking via Zoom with Kochenov’s friend. He is an attorney and drafts EU regulations at the Commission’s so-called “DG JUST.” Might he have something to do with why Kälin seems so relaxed about the prospect of a lawsuit from the European Union?

Now I’m curious. I wonder if I’ll find his name in the Henley leaks. And I do. In 2017, the board of Henley & Partners elected to hire this man. He would be their “chief government advisor.” I also find record of a payment made to him, although it was only for about nine hundred euros. I page through the Government Advisory, published in 2018, which Kälin hands out at consultation meetings with governments. Indeed, this employee of the European Commission appears therein as a member of Henley & Partners’ “Government Advisory,” along with a bio and headshot.

But there is no indication either on his EU employee profile, nor on his LinkedIn page, that he ever worked for Henley. There is likewise no indication that real information ever passed between the company and the EU employee. It’s just another example of how invaluable Kälin’s network is.

On 29 September 2022, the European Commission decided to bring charges against Malta.

15. More crises, more passports

Sociologist Kristin Surak from the London School of Economics estimates that every year, roughly twenty-five thousand citizenships are “purchased” in exchange for money worldwide. Kälin has competition. New specialized firms like Arton Capital, Latitude, CS Global Partners, and Apex Capital Partners, as well as giant consultancies like PwC, are all in the market. No one knows precisely how much money is made through the brokerage of citizenships and visas. The industry association that Kälin co-founded, IMC, claims that it is twenty billion dollars annually.

Kristin Surak reckons that there are now around seventy countries formally selling residence permits – so-called “residence by investment” – among them fourteen EU countries; and that there are “up to twenty-two countries” that offer passports – “citizenship by investment.” Italy offers the “Dolce Visa.” Portugal’s golden visa, which costs half a million euros, has been bought by over eleven thousand investors since 2012. Over two thirds of these buyers were Chinese; a few hundred Turks are also among them. In reality these could be Russians who bought a Turkish passport and used it to get the Portuguese visa – a combination that Henley & Partners recommends to many clients. Beyond that, millions of people with ancestors from the EU theoretically have repatriation rights, some until the third generation. Regardless of how the European Court of Justice rules, the EU stands open to whoever has enough money.

The rich are getting out of dictatorships like China and threatened democracies like Hong Kong, India, and Brazil. The war in Ukraine is exacerbating these tendencies. According to a study by Henley & Partners, in the first half of 2022 an estimated fifteen thousand of Russia’s hundred thousand millionaires left the country; forty-two percent of Ukraine’s ultra-rich left their country as well.

More recently there have been increasing numbers of passport customers in Great Britain – and the US. Since Brexit, Great Britain has lost thousands of millionaires, Henley & Partners estimates. In the US it is often Democrats who fear increasing instability in their home country, Kälin tells me. But not exclusively. In October, the New York Times uncovered that Peter Thiel, the tech mogul who finances radical Republicans in the US, had applied for a Maltese passport. Reporter Ryan Mac found the apartment in Valletta that Thiel listed as his residential address – on Airbnb. That a backup citizenship-as-insurance-plan is attractive to such buyers could be an indicator of a loss of trust among elites in the future of nation-states as such. Or perhaps it is evidence that Kochenov’s post-national vision, the separation of citizenship from physical territory, state, and culture, is arriving to the mainstream. The German electro band DAF once prophesied: “Wir sind die Türken von morgen.” We are the Turks of tomorrow.

Kälin won’t comment on whether Thiel is a client of his. He has experience with tech companies. Documents obtained by Das Magazin show that in 2012, Henley & Partners arranged citizenship from St. Kitts and Nevis for Telegram founder Pavel Durov, after the messenger app developer had run afoul of Russian intelligence. From then on he showed off his jet-setting life on Instagram and described himself as a “legal citizen of the world.”

Later, Durov would be granted two additional citizenships that aren’t available for purchase: those of France and the United Arab Emirates. It goes unremarked upon in a lot of the critical media reporting on passport programs that citizens are a state’s capital. It can be an advantage, a geopolitical power move, for a state to attach notably influential people to itself.

16. Golden autumn, Swiss passport, Italy

In late fall 2022, Kälin is in a great mood. He’s expecting record earnings. The new Italian government under the post-fascist Giorgia Meloni has him hopeful. They are pragmatists, he thinks, who want “positive migration.” In November, he visits Rome.

At any rate Kälin is traveling a lot. Albania, Montenegro. He’s hoping for new passport programs in the Balkans. He wants to bring me along to Africa some day, where Henley & Partners is expanding into Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa. His next big coup is to take place in North Africa: a sovereign city-state for refugees who aren’t being let in anywhere else and can’t afford to buy citizenship: the “Andan Global City.” Kälin wants to found a country. With its own passports.

In the meantime he has warmed to the idea of brokering Swiss citizenship. The application process for wealthy non-EU foreign nationals to get a residence permit has always been “rather opaque and complicated,” and you have to develop contacts with local authorities. Kälin says a citizenship by investment program could garner billions for Switzerland. But the Swiss passport would have to be the most exclusive in the world. The price? At least ten million francs. With this revenue, the country could shore up its pensions, for example. “There should be a referendum, actually.”

Translated by Antidote

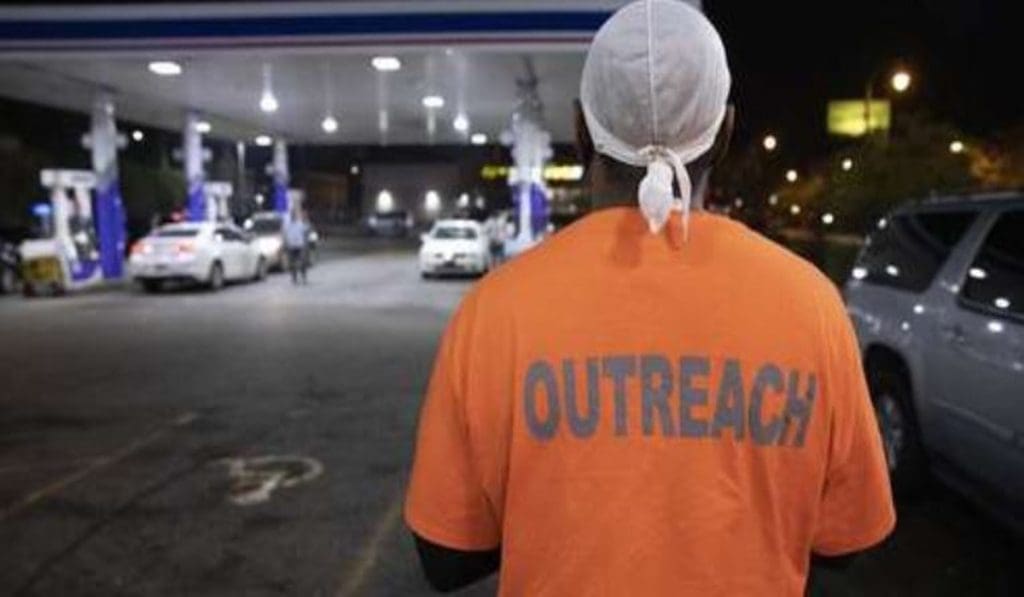

Featured image via Hannes Grassegger dot com