Transcribed from the 10 July 2023 episode of the shado-lite podcast (Chile/UK) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole episode:

Health justice is a vision for healthcare that is people-centered and liberatory. It’s about recognizing the economic, social, cultural, and political reasons for health injustices that we have around the world, and then building something that is radically different from that.

Zoe Rasbash: This week we’re asking: Why is health only a human right if you’re white? We’re really interested in issues around health injustice and we want to get into it. How did we get to this point where there’s so much racial discrimination in our medical system? What’s going on, and how do we move past it and build health systems that are free of racial bias?

This is a really huge issue. There is so much medical prejudice for so many different communities, like queer people, women, and disabled people, and we will be trying to point out these intersections, but we’re focusing on race specifically here. That doesn’t mean these aren’t all interconnected. We just really wanted to drill down into medical racism.

Larissa Kennedy: Of course the health justice movement addresses that, and we’re going to talk about some of the organizers who are doing some of this work on the ground. Let’s get into it.

I’ve been reading a lot about where the movement is going, which has really shaped my thinking. I thought this was all going to be about big pharma! I’m going to get into the People’s Health Movement and the Health Justice Initiative and all that a bit later, but they’ve made me think about the complexity of this, the range of things that we have to deal with and how we need to see them all as interconnected.

I’m really excited to get into that. I do still have questions! It’s such a massive task, to create this people-centered health sector that a lot of people are talking about, and to think about health justice in this transformative and imaginative way. My question is: if we’re coming from such different starting points—some fully privatized health systems, some public but being privatized in the moment, some that are fully public—how do we come from people’s very different understandings of what health looks like, and then communicate this vision that some people are trying to share? How do you communicate that on the ground? When people are like, I need a doctor now, I need this solution now, how do we build this collective vision and make it really resonate?

ZR: Do you want to define what health justice means? In case people haven’t come across the term before.

LK: Yes, let’s do it. Talking about health justice, we’re ultimately talking about a vision for healthcare that is people-centered and liberatory. It’s about recognizing the economic, social, cultural, and political reasons for health injustices that we have around the world, and then building something that is radically different from that. It’s thinking about the fact that a large proportion of the world’s population still lacks access to food, education, safe drinking water, sanitation, shelter; to their land and its resources, to employment, and to healthcare services—all of those things are connected in health injustice, so we have to address all those things as we move towards health justice.

I hope that gives a bit of an overview. I’m not an expert quite yet, but that’s what I’ve been reading about. A lot of people talk about building a people-centered health sector, and people’s participation for a healthy world. We can get into a bit more of what that means in a bit.

ZR: That leads onto the things that I’ve been thinking about, which was looking at the history of medical racism in the UK and the US specifically. A lot of people have heard facts like Black women in the UK are four times more likely to die of pregnancy and childbirth than white women, and All ethnic minority groups in the UK had higher risks of dying from COVID than the white British majority. All of these things have become really starkly clear. So what are the logics and histories that got us to this point?

This isn’t happening randomly. Why do we need to be mobilizing around health justice? How did we get to this point where this is such an important issue? Where did these biases in science and the medical industry come from? I’ve been looking at the work of Udodiri R. Okwandu, a PhD student who has been researching the history of medical racism in the West, and who looks at the really dark histories of unethical medical practices specifically related to race relations. Okay—that’s what we don’t want. How do we build medical and scientific institutions that don’t reinforce racial injustice? She’s listing all the sins—if we’re actually going to build something better, we have to know what’s been going wrong. It’s been so interesting.

Where did this all come from? What are the logics we have to expose to understand why these things are happening? This doesn’t happen in a vacuum. We know that racism is very present in our society, but how is it being specifically utilized in medicine, and what does that dark relationship really look like?

My questions also changed, because I thought it was just going to be about white supremacy in medicine. And it is about that, but it really tracks back to religion. Okwandu’s argument, basically, is that the racial inequalities that we see today are due to racial biases that are rooted in science. She talks about scientific racism, which is the use of scientific authority to justify racial prejudice, racial discrimination, and notions of racial superiority; using science to say, Being racist is right! Then there’s medical racism—they are two different things—which is prejudice and discrimination in medicine and in the healthcare system based on an individual’s race.

Okwandu tracks it all the way back to eighteenth-century scientists in Europe and the US who were basically just trying to find a way to justify slavery. They were looking for scientific and religious evidence to prove white supremacy right. There was this debate: physicians and scientists had two schools of thought that were basically about stories from the bible. One of the schools of thought was called monogenesis, which was looking at how Noah cursed the bloodline of one of his sons to a life of enslavement, and blessed his other two sons. And while in the book of Genesis these characters are never racialized, over time the symbol of Ham—the son that Noah cursed—became associated with Blackness, so people could justify their racism against Black people, since Black people are the descendants of the cursed son. So it’s moral to be racist, basically; it’s god’s truth to be racist.

The other school of thought was the idea of polygenesis. These scientists and medical practitioners said, White people are descended from Adam and Eve, but Black people are in fact descended from other animals that were in the Garden of Eden. So white people are descended from holy biblical characters and everybody else is descended from animals! It’s using the bible to dehumanize Black folks and people of color, to reinforce white supremacy—just taking shit and running with it, trying to find reasons their racism is a moral thing. It’s fucking wild.

You have to wonder, are there ways to improve the medical system as it is, or do we need to build something entirely new?

Then, these theories became the basis of scientific inquiry, and all these schools of eugenic thought. But it was basically just railroading science into searching for more evidence to prove white supremacy. It was like, What can we look at to prove what we already think, which is that white people are superior?

It’s how we got things like eugenics—pseudosciences that suggest bumps on a skull can predict mental traits, which we can use to justify racist beliefs through comparing skulls of different racial groups. Charles Caldwell was a scientist who said Black people’s skulls suggest they have a “natural timidness,” stuff like that. There was Samuel Cartwright, who was a doctor who basically made up a disease—he claimed that if enslaved people are freed, they’ll get a mental disorder called “drapetomania,” so it’s actually really nice of us to keep people enslaved, because we’re stopping them from getting this disease.

So people are just making shit up. Medical and scientific institutions were just making up shit and weaponizing their institutional power to reaffirm racist beliefs. Look, this is scientific! God intended it! Just to rob Black people of their autonomy and humanity, and to legitimize racist treatment.

Then it snowballed. Okwandu talks about a couple of stand-out cases in history where we can see how medicine has been utilized to dehumanize Black people, and also where medicine has used Black people’s bodies as disposable, as test sites for improving medical care for white bodies. One of the most famous ones, which is just so harrowing (trigger warning!), is J. Marion Sims, the “father of modern gynecology.” He’s known for pioneering solutions to vaginal fistula, which is when an opening develops between the vagina and another organ such as the bladder, colon, or rectum—when that happens there’s a high chance of stillbirth. Ninety percent of women who developed it ended up delivering a stillborn baby. His contribution was that he was practicing medicine to try and treat this.

But the reason he was doing that was not out of the goodness of his heart. It’s because in 1808, in the US, congress banned the import of enslaved people, so the value of enslaved women shot up. You couldn’t import more enslaved people for your plantations, but if you’ve got female slaves you can make sure they have babies and then enslave their children. So the value of enslaved women shot up because they’re able to reproduce, but vaginal fistula was considered a huge problem because it was causing lots of stillbirths in enslaved women’s communities. So it was a cash cow: If we can figure out how to solve this, we can generate more value from our enslaved women.

And he was practicing his test surgeries on Black women, but wouldn’t give them any anesthesia. These enslaved Black women were being operated on without anesthesia, sometimes ten or twenty or thirty times, so they could figure out how to have enslaved women reproduce more and also so they could treat white women—but the white women would get anesthetic. It was rooted in this racist belief that Black women don’t feel pain, and that pain and suffering was “needed” for Sims to perfect his technique. He was using Black women as disposable subjects to experiment on for white women, and for profit off of enslaved women.

One of the women he operated on was named Anarcha, and she was operated on thirty times over two to five years, with no anesthetic. Sims is held up as this symbol of medical progression and women’s health…so many Black women’s bodies were seen as expendable in order for him to do that. It’s really horrible.

LK: I knew about practicing on Black women without anesthetic, but to hear the caucasity again is still so harrowing. To feel like someone’s body is just an experimental playground!

When it comes to people’s health, to what extent do you think all of the things you’re raising about these histories has been about the proximity of certain communities to death? In this case, Black and Brown communities and their proximity to death and disposability?

ZR: That’s the root of it all, right? We’re figuring out ways that we can create logics in order for us to dehumanize Black people so then we can utilize their bodies for whatever we want. It’s like, How can we reinforce this idea that Black people and people of color aren’t human, so we can do whatever the fuck we want? It’s creating these logics of disposability, these logics of superiority for white people. It feels so rooted-in. You have to wonder, are there ways to improve the medical system as it is, or do we need to build something entirely new? The way medicine is practiced is this long and also quite invisible lineage of oppression and exploitation. Don’t we just want to start again?

We talk about this lot: can you reform or do you need to build something new there? Again, I’d heard things about some of this medical racism, but when you see the names and you see the photos…I don’t know if you can reform this. It’s so insidious.

LK: For real, though. It’s really rough to think about, the degree to which you have to position someone as literally not human in order to do these things. As you touched on at the beginning, it’s not just when it comes to Black and Brown people. This has happened to disabled people particularly—I was thinking about the distancing from humanity that takes place in order to justify some of the disgusting things that have happened in our health system. Or the LGBT community—think about the HIV pandemic, and all of the things that happened to create distance. And again, equally so with Black and Brown folks from the Global South, who were all seen as disposable. The response to health systems and health challenges today is so linked to all of these historical injustices.

ZR: The way that we think about health under capitalism is that health is the responsibility of the individual, and therefore if you are unwell, specifically if you are unwell and from a group that’s already marginalized, that’s your fault. It’s a moral issue. Those arguments have been weaponized. It’s a classic fatphobic weaponization: It’s your fault if you’re sick. It itemizes health as this single thing, and you are singularly responsible for it.

And we can’t have a productive conversation around health if we still think like that, because obviously health is an ecosystem. Health is a collective. You can’t be healthy if you live in poorly-ventilated housing, or you don’t have access to fresh, healthy food, or if you don’t have access to green spaces to exercise, or if you’re living in areas where there’s much higher air pollution. You can look at cities all across the UK and all across the world: working class communities of color are going to be living in the most highly polluted areas of the city. How can you have a conversation around health being individualized when there are all these systemic impacts that impact our health every day?

It’s all so entangled. And what health justice does is give us a lens to start thinking about all these interconnections. But it’s really hard to have a productive conversation around health when we think like, You should quit smoking and then you’ll be healthy. There’s so much more to it.

Literature from organizing communities gets into the fact that ending occupation, ending war, and ending violence is part of the health justice movement.

LK: What I’ve loved about some of the stuff I’ve been reading, as well as what you were saying about classism and racism and fatphobia and all of those things being intertwined, is also thinking about war: how does refugee status, how does asylum-seeking status, how does climate breakdown—how does people being put in precarious positions by systemic issues, often originating in the Global North and being further perpetuated by the Global North, cause further health problems for those in the Global South? Time and time again we’re seeing Black and Brown bodies and health being put through the ringer because of decisions made by largely white people in the Global North.

It was really eye-opening doing my reading, because of course I see violence, conflict, natural disasters (and those disasters’ being fast-tracked by climate breakdown) as being crucial issues that we need to be thinking about—but I hadn’t necessarily thought about them in relation to health. I absolutely love that some of the literature that I’ve been reading from organizing communities gets into the fact that ending occupation, ending war, and ending violence is part of the health justice movement. To situate it in that way is so powerful.

ZR: In a couple episodes, we’ll be looking at who has to die in order for us to have an iPhone. We’re all aware that all these supply chains, the products that we access, the things that we consume—these are international supply chains where labor is outsourced to whichever country has the least labor protections. For us to own the tech, and to own the clothes—whose body is on the line for that? Who is working in these places where it’s basically a form of slavery? You’re in proximity to hazardous chemicals, your body is put on the line every single day, you’re working unbelievable hours, you can’t have a day off, and you’re told that if you don’t work like this then you’ll be destitute. Again, it’s Black and Brown people. Specifically, we’re going to be talking about China—but holding these supply chains to account is, again, a health justice issue.

Another interesting part of Okwandu’s research was looking at not just how medical racism used Black bodies as test subjects, but also how medicine was weaponized to depoliticize the civil rights movement, which was something I hadn’t thought about before. She talked about how in the 1960s in the US, obviously there were these rapid social changes happening—the civil rights movement, organized protests to full-on riots, racial solidarity, Black power, Black consciousness—and how Americans at that time were associating strides for Black liberation (whether it was through the media or politics) with social unrest.

There were these two Harvard doctors who were key in constructing an idea of civil rights protests as senseless violence, using their power as doctors and using the power of medicine and science. They published a paper in 1967 called “The Role of Brain Disease in Riots and Urban Violence,” and their basic argument was: We’re focusing too much on the socio-economic indicators of rioting; poverty and lack of opportunity and education. It’s not really about that! It’s actually biological factors. Their argument was that it was actually a brain disease. They were trying to associate people fighting for Black equality with having a brain disease: The people who are rioters, it’s not because of the socio-economic conditions or the racial injustice that they’re experiencing. It’s actually that they’ve all got a brain disease!

They were given five hundred thousand dollars by the US department of justice, and used medicine to associate the fight for Black equality with brain disease. This is a quote: “We’re talking about being socially cost-effective. If you can work out a way to define, diagnose, and treat—and even prevent—a problem, you’re going to save a lot of money.” Talking in the language of money, using medicine to depoliticize the civil rights movement. That got spun and became hugely influential in the way that white Americans were viewing civil rights protests at the time.

As for where we are today—I mentioned it earlier: high rates of COVID in ethnic minority communities, Black mothers more likely to die from childbirth, Black people less likely to receive treatment for pain because many doctors are taught or hold onto a belief that Black people are less likely to feel pain, or they’re less likely to be given pain relief because there’s an idea that if they’re given opioids, Black patients will abuse them. So there are these legacies of racial and medical biases that are built into how doctors are taught, how medical school works.

It’s really insidious. A lot of people have probably seen the stuff around textbooks: doctors don’t know how to treat skin diseases on Black patients because the only pictures in the textbooks are on white people, and they look different on different skin. So Black people are going to get less treatment.

LK: There are different outcomes because medical racism is literally being taught to young doctors!

ZR: It’s a question of education, one hundred percent. Changing how medicine is taught—if we’re talking about where the key levers for change are, that’s a big one. Changing medical schools, having a broader conception of health, having health justice and much broader understandings of what impacts our health taught to doctors, and having more diverse people write the fucking medical textbooks—that’s doable. That’s a doable thing, to change how medicine is taught.

LK: It is. It’s doable in theory. But when I was a student union officer (hashtag #StudentMovement!), we were working on a decolonization campaign—this is back in 2018—and we were fighting for a pilot of this campaign where you would actually remunerate students to do this work. We wanted to do it across four really different departments. We had classics, history, and so forth…and we wanted to do one in medicine. And everyone was up in arms about the idea that you would decolonize medicine. You can’t do that—it’s just medicine! The reaction to the idea that there is an issue in educating medics was so visceral. It took so much time to cut through.

ZR: Do you think it’s that same thing again? It’s science so it’s objective! It’s not affected by racism, because science is truth! Do you think that’s what the vibe was?

LK: People hate the “decolonization agenda” anyway, but they can at least understand why it sticks in English or history. But when you move over to science, and specifically medicine, people are so up in arms. It’s this idea that we have created something that is above any of these nonsense words, these nonsense critical race theory things! They think that you’re trying to bring gobbledy-goop into something that’s really serious. It’s interesting to watch people foam at the mouth over the idea that medical teaching is racist.

ZR: It’s so interesting that you’ve got that experience of pushback. Medical science is an objective truth? Who wrote these truths?

LK: Who wrote these truths? Who died and was injured in order to make these truths possible, to even know some of these things? And where do you go from there?

Shout out to one of the doctors at my university who did loads of research on what medical students were learning, which made the case for why we desperately needed to decolonize medicine at my uni.

Workers of color, particularly women of color, are over-represented in many service sector occupations, so their exposure to COVID was much higher. And because they live in polluted areas, their likelihood of getting the worst type of COVID was much higher as well.

ZR: It should probably be really easy to decolonize medical education but no, it’s incredibly difficult to do any of this stuff. People are campaigning all the time for these changes. It feels like something tangible that needs to change, now.

The last thing that I looked at was talking about COVID as a recent case study. I looked at an article from the Harvard Gazette that said with COVID’s spread, “Racism—not race—is the risk factor,” and explored how racism affects the spread of COVID-19. They said society blames persistent health disparities in Black communities on personal choices rather than reflecting on effects of institutionalized and systemic racism, and social, political, and economic disenfranchisement.

They draw on the history of environmental injustice in the US in the seventies, and how communities of color, specifically lower income communities of color, were more exposed to polluted air, water, and land than those in white areas. They are much more likely to be living near landfills, oil fields, waste sites, factories, toxic pollution, areas with high automobile traffic, near main roads, because dirty industries and government were met with much less resistance to putting facilities and roads in neighborhoods where residents aren’t part of the decisionmaking processes. It’s a reflection of the racism within the government; these decisionmaking processes then have a direct impact on the health of those communities.

The article talks about this in relation to COVID. Public health experts were saying that those racial disparities have contributed to higher rates of respiratory and cardiac conditions, and those things put COVID patients at higher risk of hospitalization or death. So basically, those who live in regions with high levels of air pollution are more likely to die from the disease than people who live in less polluted areas. They looked at a load of papers and saw that long term exposure to air pollution increases vulnerability to the most severe COVID-19 outcomes.

Other environmental factors also contribute heavily to this problem: living in crowded conditions forced by poverty makes social distancing impossible; lack of healthy food options; problems with access to medical care; and great prevalence of complicating conditions such as diabetes, heart failure, and kidney disease. Also, from a labor perspective, we know that in “essential worker” positions, people were much more exposed to getting COVID. In the US, where these studies were being done, workers of color, particularly women of color, are over-represented in many of these service sector occupations, so their exposure to COVID was much higher. And because they live in polluted areas, their likelihood of getting the worst type of COVID was much higher as well.

The article is about how all of these things contribute to health. COVID is such a clear case study of how it’s not just about whoever catches it, catches it. All of these things contribute to the level of exposure you’re getting, and the level of severity that you’re getting, and the likelihood that you’re going to die from it. It speaks back to that point we were talking about earlier, that in the West we have such an individualized lens on how we understand health. Your own health is something you’re responsible for, and therefore when it’s depleted you’ve done something morally wrong and you are to blame. It helps eclipse the state from being culpable in our collective health and well-being.

It’s saying, It’s not our fault, it’s your fault, when actually health is collective. The state is responsible for the health of its citizens, these ecosystems affect our health, infrastructure affects our health, and we need to be holding our governments to account for these health disparities, this medical racism, the unequal impacts of diseases like COVID. The government has a massive role to play.

This probably leads on to what you’ve been working on, which is that health justice gives us a lens to see the racism and biases within our medical system, and how health is about how we need to think about constructing our society. We can’t just think about it over here anymore, it doesn’t work like that. So I’ll pass it to you—what have you been reading, what have you been talking about?

LK: Yeah—you’re so right, COVID really woke a lot of people up to the fact that health justice is interconnected with everything. Especially the struggle for access to the vaccine made a lot of people sit up and think, Maybe there’s a bigger issue here! Maybe our global health systems are rooted in colonialism! This is what health justice movements and health justice community organizations have been trying to say, for the longest.

I’ve been reading about the Health Justice Initiative in South Africa and the work of Fatima Hassan, and the Cape Town Call to Action—I can get that in a second—but also the People’s Health Movement in the US, which has some really interesting learnings around movement building. Also things like Just Treatment in the UK, which I think a lot of people don’t necessarily know about—at least I didn’t know about it before a couple of years ago. So yeah, that leads perfectly into talking about what the movement is saying about where we go from here.

When we’re talking about health justice and the people on the ground who are fighting for health justice, it’s about positioning health as a human right. As you were saying, it’s not about personal interests. It’s about health being seen as a universal concern. Everyone shares this responsibility; states have to share this responsibility, as you were saying. This is also about rights of access to healthy food, clean water, sanitation, housing and shelter that is actually adequate for humans to be in, steady employment, public health information, all that good stuff.

What I really want to share from my reading is about what’s been happening in South Africa. There’s the Cape Town Call to Action, led by People’s Health Assemblies in South Africa, that has been a catalyst for the People’s Charter for Health, which is part of the People’s Health Movement. Let’s get into all of that.

In South Africa, the People’s Health Assembly is a flat structure, a transformative way of building a shared vision for the health movement. But let’s rewind a little bit and set the scene for what the health situation is in South Africa. That’s important to know. I don’t fuck with the World Bank, but research from the World Bank found that the top one percent of South Africans control 70.9% of the country’s wealth, while sixty percent of the country’s population collectively controls only seven percent of the country’s assets. That is to say, the economic injustice in South Africa is super high, and that is also still split along racial lines in a post-Apartheid situation. It is both economically and racially very divided.

That’s important to know; it almost serves as a microcosm for the world. That’s one of the reasons that South Africa has been such a big proponent of the health justice movement. South Africa has seen how, along racial lines, along class lines, a lot of people have been disproportionately exposed to things like HIV and AIDS, and communicable and non-communicable diseases, as well as violence and injuries as a result of violence. People have then been able to address the fact that social injustice is inherently interconnected with health injustice.

They’ve been thinking about solutions—how we don’t just tinker at the edges, but actually grasp at the roots of this health injustice and think about what a people-centered health sector and people’s participation for a healthy world look like in South Africa. A lot of that thinking really deepened and was a catalyst for the People’s Health Movement and the Charter that then came from that.

In the global healthcare system, the priority isn’t healthcare—it is how to extract profit from people’s need for healthcare.

ZR: Obviously the framing of this movement is on people-centered health. When we look at our medical system now, if it’s not centered on people, what is it centered on? What are they framing it as that’s different from what it is now?

LK: Wonderful question. From what I can understand, the current basis of the global health system is an economic and profit-incentivized one. The Charter talks about the alienating function of the neoliberal health system and how the needs that shape the health system as it is are essentially capitalist needs rather than health needs. It’s talking about political, financial, agricultural, and industrial policies that are shaping the health system, but not from a point of view of needing to create solutions to health problems, but of trying to push the greatest amount of profit into the hands of the owners of big pharma. It’s essentially been about big pharma lobbyists and how when it comes to the health system as it is, the bottom line is the bottom line. It’s their bottom line and their profit incentive that is driving a lot of the healthcare responses that we see.

It links to what you’re saying around the COVID impacts. I think it can also be quite hard to envision that from a UK positioning, because we don’t see it as clearly, because we have a public healthcare system. But ultimately, in the global healthcare system, you can’t shy away from the fact that the priority isn’t healthcare, it is how to extract profit from people’s need for healthcare. The Charter also talks about how it’s not just that economic policy is tied to healthcare—it’s also about the withholding of particular drugs, and of particular knowledge.

For example, if we look at the Just Treatment movement, they’re tackling Vertex, which is a big pharma company who have a monopoly on cystic fibrosis drugs. One of the core things that Just Treatment has to say as a movement—and the message is really simple—is that our health should always come before the interests of private corporations. As things are in the moment, there are patents on life, essentially. There is bio-piracy of traditional and Indigenous knowledge and resources as well. Essentially, people are saying, I know that you knew that for hundreds of years, but I know it now and I’m going to make that my personal knowledge and I’m going to profit from that knowledge. Which is disgusting!

Shout out to Just Treatment, because as of now they have submitted petitions to governments in South Africa, India, Ukraine, and Brazil to suspend or revoke Vertex’s patents. Hopefully that comes through for those who need those drugs for cystic fibrosis. But this is just one example of how this functions, and it really clearly demonstrates how this system is not about health, it’s about profit. And we know that racial capitalism and the way that it functions means that this all disproportionately falls on the shoulders and the bodies of Black and Brown people. Of course this impacts people who are working class; it impacts the poor far more than any of those who can afford private health care and access to these drugs, access to this knowledge and these resources.

What I also think is interesting about the Charter and about this vision for a people-centered health sector is that it gets into problems around colonialism and racism. It gets into problems around environment, it gets into problems around violence. Let’s jump into that more as well.

One of the other problems that this Charter raises is the colonial-neoliberal economic system and how it negatively impacts global healthcare. It talks about things like cancellation of Third World debt, and radical transformation of the World Bank and the IMF, and completely disrupting the economic system as we know it, as necessary for health justice. When you say it like that, it feels obvious. But in my head I hadn’t necessarily linked those things. It was really powerful to see it stated: obviously we have to cancel debt in order to distribute health justice.

Then, how do we even think about health justice without addressing the fact that millions of Black and Brown people’s lives and livelihoods and health have been impacted for literally centuries because of colonialism? What does it mean to look at reparations? What does it mean to think about that and the impact on health? I thought that was really interesting, too.

And then social and political challenges: the need for full participation of people. I thought this was a really interesting framework. How do we make sure that all of us have agency over all of our health? Sometimes health feels like something that’s like, Oh, leave that to the doctors, leave that to someone who’s smarter than me. But one of the really big things in this charter is that it spans across seventy countries and thousands of organizers who have contributed to it and to this movement. It’s not just about doctors, nurses, and healthcare professionals; it’s also about the people and how they exercise demands and accountability over those who have power in the healthcare system, which I think is really powerful.

ZR: It reminds me of the evolution that the climate movement has seen: at first it was like, This is an environmental phenomenon, this is a scientific issue (and of course big up to all the scientists who have been pushing for climate action for decades), then people came to realize that health and climate are not just scientific issues, but deeply political, deeply about accountability, about justice, about governance and decisionmaking, about participation. It reminds me of Extinction Rebellion pushing for citizen’s assemblies to make decisions around climate. At first people were like, It should be just the experts and the scientists! But no, it’s a people’s issue. It doesn’t exist over here in an echo chamber. It’s very much integrated with everything we experience and see in our society.

Super interesting, the parallels between the two.

LK: That’s so true. This is ultimately what we mean when we’re talking about building a different and better world—people have to be part of the solution. When you feel alienation from a solution, it’s almost like, Oh, someone else will fix it, or Someone else will come up with something better. Why can’t we as a collective think about what we need? We are the experts, we are the knowledgeable people in our own lives and our own communities.

There’s really localized focus on this—even though it’s a global health movement, I love that it has really localized focus. You could literally go and look specifically in countries, in regions, and in communities, and what they’re doing on the ground is really cool. I would recommend a look if anyone is interested.

What you said about the connection with the climate movement and the similar ways of organizing also heavily links to what they’re saying about climate in the Health Charter. Ultimately we’ve got a huge problem here when it comes to the impact of climate breakdown on the frequency of disasters, and also on the consequent injury and displacement that people experience because of climate breakdown. They’re seeing this directly as a health justice issue. It’s not just intertwined because of the ways that we need to organize; it’s intertwined because we can’t have health justice without addressing climate breakdown. That’s a really powerful message to send.

The way that climate change is already impacting the UK is very much through health injustice. It’s insidious because it’s quite invisible—people think of climate change as being a flood or something.

Let’s be so for real: when we’re talking about climate, this isn’t about something that is situated far away from us. This is really impacting the health outcomes of people. We’ve already talked a bit about the impact of air pollution and so on, but there’s also rising water levels and the very real impacts that will have on health injustice. Who is actually going to be able to be healthy, both physically and mentally, when the very real impacts of climate breakdown are literally here, coming for us?

This reminds me of Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Barbados, talking about how a lot of the countries that exist now didn’t exist when the UN was set up. She said this at the UN general assembly a few years back. A lot of those countries are the ones now fighting for their existence, because they are feeling the impacts of climate so much more in the Global South. It’s the same set of issues because of climate, because of neo-colonialism, because of all of these things: the health outcomes for folks in the Global South and the impacts of climate on their health outcomes are just so much worse.

It’s actually disgusting to think about how much we’re not talking about this. This reading has made me feel quite disgusted with the fact that I haven’t seen a live enough conversation about this in our movements. How do we stand in solidarity around this?

ZR: I’m based in London, in the UK. I work in climate, and people say to me, When’s climate change going to happen? There were nine hundred excess deaths in the 2019 heat waves here. Those people were predominantly people living in unventilated social housing who had pre-existing health conditions or disabilities. Old people and young kids. The way that climate is already impacting the UK is very much through health injustice. It’s insidious because it’s quite invisible—people think of climate change as being a flood or something. The way that our temperature is changing, those with already marginalized health are being put at risk. But like you said, the conversation isn’t live enough; we don’t have the language to be able to see these intersections. It feels too complicated for our policymaking processes to be able to handle.

LK: Tell them again, honestly! It’s so true. Another interesting thing about that is this Charter is trying to deal with so many issues from the short term to the medium term to the long term—it’s so ambitious in wanting better in the here and now but also recognizing that there’s so much in the current system that just cannot be reformed. You can’t just play with it. You can’t just move this around and hope for the best. As you say, it’s insidious—it’s so seeped into this system that people are seen as disposable. Those lives aren’t seen as a loss. It’s just seen as, Oh well, that’s a shame. It’s not in the news, it’s not being talked about, it’s not being acted upon. It’s seen as par for the course in so many ways. This again goes back to what this Charter is saying about alienation and individualization under this system.

Let me tell you a bit more about some of the other bits. One of the other issues that the Charter raises is violence. It’s talking about the impacts of war and conflict on health outcomes. With no hesitation, it states that we need full-scale disarmament in order to deliver health justice. It also says we need to deliver the end of occupation. And it sets out that we need independent, people-based initiatives to declare neighborhoods, communities, and cities areas of peace and zones free of weapons.

This covers so many issues. It covers the occupation of Palestine. It covers gun rights in the US. So many things are swept up in this piece. It’s really interesting. But ultimately, when we think about it, they are all interconnected. The use of weapons, the use of violence, and the way that impacts health, and who that impacts, is so important. Particularly in this moment because of everything going on—my thoughts are with those in Sudan, those fighting for freedom in Sudan. How can people who are fighting for their lives be thinking about health outcomes in this moment? It’s such an impossible question. But the Charter perfectly explains why it has to be a consideration for all of us, if we’re serious about health outcomes, and the vulnerability that things like violence and conflict cause for health outcomes.

All of this is to say that yes, this is about connecting very localized movements; it’s about spanning across these seventy countries; it’s about raising the voices particularly of those in the Global South—but because it’s so wide-ranging, it essentially says that health justice and building a people-centered health sector is about everything. It connects literally every facet of our lives, from economic challenges to social and political challenges, environmental challenges. All of it is connected into ensuring that people are healthy. But on the flip side of that, it means that the policies and processes that are shaping our lives and shaping our governments are leading to health injustice—it can no longer be seen as this separate, disconnected, stand-alone area. It has to be seen in tandem with literally everything else. That’s the biggest thing I’ve learned from reading about this, and that’s the most interesting and striking thing for me around all of this.

The other thing that I want to talk about is, where does the movement go next? As I said at the beginning, we’re coming from such different standpoints on this, it strikes me as difficult to communicate on the ground how one struggle connects to the other. How do we see this as a joined-up, united movement? I didn’t necessarily come up with an answer for that. I think this Charter is very ambitious in doing that, and you can tell that the people who are heavily involved in this can absolutely see those links. But on the ground, what does that actually mean, and what does that look like? I’m really glad they posed that question for me, because it almost feels like a challenge.

ZR: There are so many amazing groups working at these intersections. I won’t lie: I hadn’t really thought about health in this expansive way until I saw some speakers from Health for a Green New Deal talk extensively, and clearly, about why health is a climate issue and climate is a health issue, and how when we’re mobilizing around a just transition—there’s a lot of energy behind the climate movement. Generally, across the board, in the UK anyway, people agree that climate change is real and we should do something about it, and there are people working super hard to make it clear how this is a health issue as well, and doing the work to articulate these intersections in a clear, tangible way.

That helps both sides: people can feel really overwhelmed by climate because it feels so distant for so many people, whereas we all have an understanding of health. We have all been unwell; we all know people who have been unwell. It gives a point for people to hold onto. If you live in a country like the UK, the impact of war can sometimes feel distant—but actually health can be a good starting point to get people to understand, Okay, this is my body and this is how it’s impacted, and how, spanning out from that, all these things are interlinked.

But you’re right. These are big questions about how we make space for these complexities. But I’m finding it really energizing that you’re sharing all this stuff about the movement. It’s just such amazing work. There’s always people on the ground doing the work!

Housing and healthcare are inextricably linked. If you don’t have safe, warm, clean shelter, how can you have any proper health outcomes?

LK: That’s been the most energizing thing for me as well, to know that people are there. People who really believe that something better is possible and are working towards it—it’s just so beautiful to see. It makes me think about how we could connect up these movements in a better way. Because how did I not know that they were out there? Obviously part of me would think this was happening, in the back of my brain somewhere, but if it weren’t for this episode I wouldn’t necessarily have sought that out.

So much about our lives under racial capitalism is very alienating. Even within our movements, often we reproduce that. If we’re talking about the very real impacts of climate breakdown in the UK, how do we then think about where that interlinks with the impacts of climate breakdown in another country? And how does that then link to health implications for people in the UK and for people in that other country?

We’re asking a lot of ourselves, but the challenges that we have ahead of us—I’m going back to what they were saying about full participation. They literally call it “the participation of the people of the world,” which I just love as a phrase. That requires all of us to be thinking about this and to be acting on it. I would love to start seeing more of these conversations live and active in our movements. When I was reading the Just Treatment stuff—it feels so silly to just sign a petition, but I obviously did that. I thought, Is there anything else I can do? and I started following some groups—it’s been really nice to feel like there’s a way to connect into, or at least listen to and learn from those movements that have been submitting petitions to governments in South Africa, India, Ukraine, and Brazil.

ZR: It’s overwhelming to try and figure out how we articulate these complex insights and issues, but there’s something so liberating about acknowledging health is a collective struggle, a collective effort. There’s something liberating in seeing how bad the world is and being like, No, but I’m a part of this system, and what I do, how I spend my money, the things that I buy—I’m not out here saying that individual actions can change these systemic issues, but we are agents of change within the systems that we live in, and the actions we have and the choices we make impact our global collective, and our health as a global collective.

If enough of us give a fuck, there is power in individuals coming together to ask questions of these systems. I feel liberated in a way, thinking about it through that framework. And I feel liberated as well in having to question these assumed truths that we have, like this idea that medical science is completely objective. No, we can trace these histories back about how medical research is totally dependent on how it’s funded and what’s profitable, and what the dominant ideology is trying to reproduce. I’m not saying we need to get our tin hats on and forget all science, but we have to start questioning truths that are being forced upon us. We can have a healthy discussion about how science and medicine are weaponized in order to oppress some people and hoard wealth for others.

We’re not tin hats here, but nothing is without critique, without question. Some of these truths—it’s so in-built to not question them, because by questioning these institutions it feels like you’re being a bad person. What about the doctors and nurses? But we’re talking about big pharma, we’re talking about the monopoly that it has over healthcare. People are losing their lives.

These are really healthy conversations to be had, and it reminds me of the popularization of abolition, and broad swathes of people being forced to question the police and the criminal justice system, which felt like such assumed truths for so many people. How much more mainstream is abolition now compared to a few years ago because of the movement for Black lives? It’s unbelievable. We can only hope the same thing for this health justice movement waking us up to the reality of these systems.

We’ve been told that this is the way things have to be, but this isn’t the way things have to be. And there are people not just critiquing these systems but actually building alternative ways of doing. That’s powerful as hell.

LK: I just hope that we can think more radically about what it means—similar to the abolition movement, as you were saying. What does it mean to begin to model what healthcare looks like beyond a profit-driven health system? That is more complex, because obviously medical care is something so serious—but how do we start that by talking about access to water, sanitation, housing? The housing piece, for me, is particularly interesting. That is often, again, seen as its own separate thing. But of course housing and healthcare are inextricably linked. If you don’t have safe, warm, clean shelter, how can you have any proper health outcomes? This doesn’t make any sense.

I would love to see if there’s anyone trying to create a housing justice campaign that links to health justice. In my reading, I was really trying to find more stuff that was interconnecting with things, but it’s hard to know what you don’t know. But framing it in this way, it feels like there is so much potential to link people’s basic daily needs into a broader movement. It reminds me of the work of the Black Panthers in meeting the immediate needs of the community, when it came to the free breakfast programs for children. What is the need? People are going hungry, or they’re struggling economically when it comes to food. Can you meet that need, and use that as a point at which you bring people into the movement?

I feel like there’s something similar here. Can we think about where housing movements and renter’s unions and community unions can start to talk about the impacts of poor housing on health, and use that as a springboard for connecting into the broader movement?

I feel energized by all of the action that people are taking all over the world, and how it’s really global but really localized. That’s really hard to do, that kind of campaigning.

ZR: You’re right. Housing is such a tangible way for us to have a conversation about so many of these things which interlink. The home, the house, is a way to see all of that. We know that housing is a tool to combat climate injustice, because if you have decarbonized, healthy, safe, warm, comfortable housing, you’re bringing down emissions from your buildings and you’re also fighting wealth inequality. Especially if those homes are accessible, then you’re starting to have a conversation around ableism. There are these groups mobilizing, and there are things like homes, like houses, where it does all come together: just the right of people to have a good life. It means addressing all these intersecting things.

We’ve talked a little bit about what gives us hope and what our action is for this week. But what is your action for this week, Larissa? What do you think we can take forward in a meaningful way to contribute to the movement here?

LK: I am definitely going to be looking more into the People’s Charter for Health and the groups that are organizing around the PCH. There is a call out from the People’s Health Movement to endorse the Charter. They’ve called upon individuals and organizations to join the global movement by endorsing it, and demonstrating within your community how the work that you’re already doing connects into the People’s Charter for Health. I’m definitely going to be taking that to the folks who I organize with and explaining what it is, how it connects, and then hopefully linking up or connecting in with other groups organizing around this.

As people might know, at the moment I’m in Chile, and there’s definitely amazing things going on with the agricultural industries here, and again, the policies around agricultural industries are very interlinked with this movement, and the drivers of those policies are very interlinked with this movement. Moving from profit-centered to people-centered and seeing that as part of this would be an amazing way to connect the climate justice and health justice work.

What gives me hope is definitely what’s going on on the ground—specifically, for me, the solutions around rejecting patents is a huge one for divorcing the power that big pharma has in this space, and moving towards something far better that actually centers the rights of people. Because healthcare is a right. I’m inspired by that lens and by the people working around it.

Zoe, what are you thinking? What’s inspiring you? What are you taking away?

ZR: All of the organizing that you’ve talked about today—it’s always so amazing; when you’re down, people are busy and doing stuff! I’m also going to be checking out all the resources that you’ve been looking at so I can clue myself up. I’m already feeling more informed to have this conversation with other people. This has been a total master class for me in really understanding the legacies of racism and the ongoing issues within our health system. It feels like a conversation I can have with people who might normally be difficult to have a conversation with about climate injustice, because they might think, That’s woke agenda nonsense. With older relatives who might not always be open to having these conversations—they are concerned about their health. That’s such an interesting leverage point to open up a discussion like this, and I feel way more informed to have those discussions.

But I’m also really inspired by the points you were making around housing. I just moved back to London, and I’m a member of the London Renter’s Union, and hoping to get more involved with my local group. I’ve been beefing with my estate agent so much because our house is a shambles, and I’m really excited to take some of these questions and these thoughts that we’ve been having into that group and into that space, and see what the opportunities are for talking about it, mobilizing around it. What does that look like in this space, in my local context?

That’s going to be my action going forward. It’s exciting. I do feel energized by all of the action that people are taking all over the world, and like you say, being really global but really localized. That’s really hard to do, that kind of campaigning.

We’ve got to wrap up somewhere, so that leads us on nicely to what’s happening next week. I’m already so excited—my brain is buzzing from this conversation and how it already links to so many of the other discussions we’re going to be having, particularly the conversation we’re going to be having in a couple of weeks about Apple, iPhones, and the dark history behind tech. There’s so much that is so linked up with that, and I’m really excited to explore those intersections more in detail in that episode.

Larissa, what’s happening next week?

LK: Next week I’ll be speaking to some amazing organizers all about food sovereignty. This is so exciting, because within the People’s Charter for Health they actually talk about the importance of people-centered agricultural policy and the impact on health. It’s all so interconnected—getting to talk about food sovereignty with people who are on the ground and doing the work and know what this is all about, inside and out—I could not be more excited.

Who gets to decide where our food comes from and why? And what does agency over that mean? We’re going to get into it, don’t you worry.

ZR: As always, let us know your thoughts and feelings—if you’ve been involved in any of this, we’d really love to hear your thoughts about some of the questions that we still might not have the answers to. Let us know! Let’s crowdsource some other actions, let’s crowdsource other things we need to be looking at and thinking about in relation to this. Excited to hear from people!

Thank you so much for joining us on shado-lite this week, guys. Have a great week.

LK: See you soon!

Contact: @shado.mag (Instagram), shadolitepodcast[at]gmail[dot]com (email)

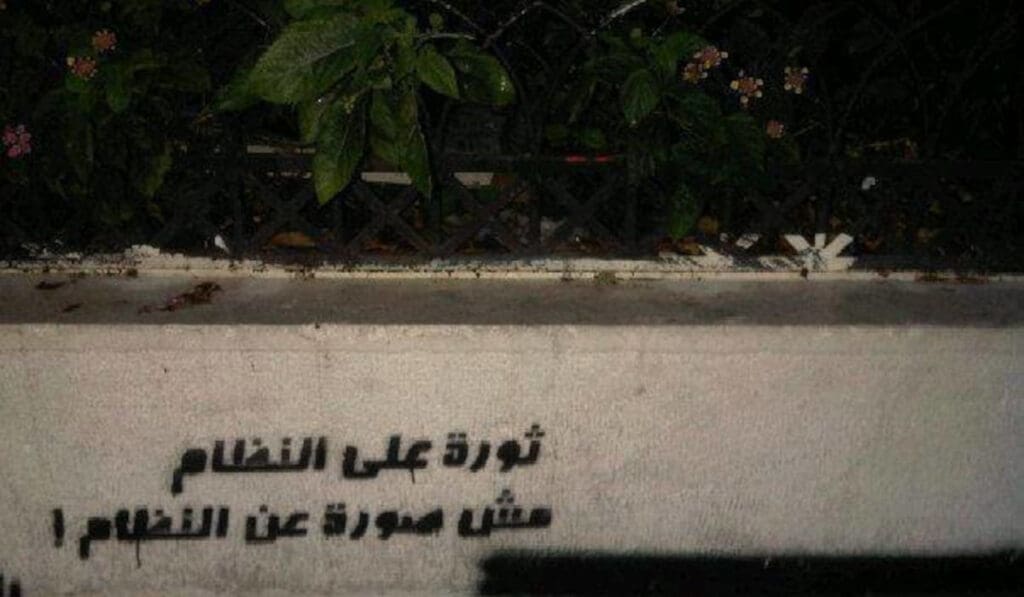

Featured image via People’s Health Movement