Three Encounters with Elias Khoury

by Tamer Nafar for Haaretz

translated by S., an Israeli anarchist

19 September 2024 (original post in Hebrew)

Two weeks ago, after yet another person was murdered in Lod/Lyd (اللّد ), I finally decided to read the book Children of the Ghetto: My Name Is Adam by Lebanese author Elias Khoury. I wanted to see if there was any connection to make between the character in the book, a man born in Lyd in 1948, and the wave of murders in Lyd and in general. Unfortunately, as I read the book, Adam’s character died by suicide, another resident of Lyd was murdered, and Elias Khoury passed away.

The first time I encountered Khoury was also the first time I decided to read a book on my own. I was staying at my first show manager’s place in the north—this was when I was first becoming well-known and performing. During one of our long night conversations, I pointed to the dozens of bookshelves adorning his house and admitted to him that we didn’t have books at home. I did not come from a home where books were read—it was only in the last decade of my father’s life, after he suffered an accident and moved to a wheelchair, that he decided to study, read, and write, and filled the house with Islamic books.

I defended myself from my manager, an intellectual, as if I had been accused of something: Leave me alone, the wisdom I bring is from the street! And if it’s a matter of culture then I’d rather watch movies. He explained that it didn’t make sense for me to write stories without reading stories, and he pulled out two books just at hand, as though he had prepared them in advance to set a trap for me.

One was the 1975 booklet To Be an Arab in Israel by Fouzi el-Asmar, who grew up in Lyd, in the back-of-the-yards neighborhood now known as the “Arab Ghetto.” As a boy, el-Asmar had witnessed the occupation of his city by the Israel Defense Forces in 1948. The second book was in Arabic: Elias Khoury’s Bab Al-Shams (2002; English title is Gate of the Sun). Just holding it in my hand was enough to give me an anxiety attack: Not only is it thick (544 pages!) but it’s in Arabic. Not that I couldn’t read Arabic—I actually read and wrote well—but my eye was more used to Hebrew from reading Hebrew subtitles at the cinema.

I decided to impress the manager and read both books—I can’t remember which one was first. But reading Bab Al-Shams was the first time I truly drowned in the stories of the Nakba. Before that, the Nakba had been a kind of rain that people around me sprinkled down on me, at random or at Nakba events when someone of that generation would come on stage and tell their stories. The first time I undressed and dove into the depths of the Nakba was with Bab Al-Shams. I really drowned in the blood of the characters, the tears of the characters, and my own tears—sometimes I couldn’t tell which of us was crying.

One of the things I remember most about Bab Al-Shams is the flies—the number of flies, and the size of each fly that appears just a moment after someone dies. It reminds me of the flies I’ve had to shoo away every time I’ve found a body (that’s a story for another time). Something about Khoury’s descriptions of the flies during the ’48 massacres of the cursed Operation Dannyi is similar to the flies that arc over the bullet-ridden vehicles of assassination victims in Lyd. There’s something about them: they are the residents of this damned place, more so than the Ottomans, the British, the Palestinians, and the Jews together. We will keep being displaced; the flies will remain homeowners.

I never understood why the fly is not considered the Angel of Death. He is black, scary, has wings, and is the first to be at the scene of death—as if he was there all along and couldn’t find release until we arrived.

My second encounter with Khoury was in January 2013, when Israel decided to annex areas near the Jewish settlement Ma’aleh Adumim in the West Bank, and young Palestinians decided to establish a tent village as an act of resistance. The village was named “Bab Al-Shams,” after the book. In solidarity with this Palestinian action, I put out a song with the same name. I brought the book’s characters back to life and had them dance with the founders of the new village until they could not be distinguished from one another, just as Khoury does with our tears and the tears of his characters.

I got an email from Khoury about the song, which had somehow reached him. He really liked the concept, complimented me briefly, and then gently criticized my pronunciation—I guess I was off by a little bit here and there. I answered with an effusive thank you, like a teenager meeting his idol, and I joked that if they start arresting people for their pronunciation, he should make a huge island to save all the rappers. Of course, before I clicked send, I asked a poet friend of mine to proofread it.

My third encounter was in person, in Berlin. The movie Junction 48 (2016) was done; the director, my friend Udi Aloni, and I decided to do a personal screening for Khoury, who was an idol for both of us. Khoury watched the movie; Udi watched Khoury watching the movie; and I eagerly imagined going back to my first stage manager to close the circle by saying, Dude, I put my literary side and my cinematic side together!

In retrospect, I realized that Khoury had been in the middle of writing his next novel at the time, Children of the Ghetto: My Name Is Adam, which takes place in Lyd. Every time Junction 48 cut to a new scene, he looked at me like Shazam for locations and said, This is Al-Khadr church, right? and This is Khan el-Hilu? Khoury had never visited Lyd, but he was able to identify every millimeter of it just from the research he was doing and stories he’d heard.

To our delight, he loved the movie, and he had no notes on pronunciation. It is our world now, the third generation since the Nakba; it has moved a bit away from Khoury’s Adam, shaped by death holes—but not from death itself. After all, none of my friends call me these days to ask, Have you heard of Operation Danny? We’re more in the phase of, Did you hear about the assassination that happened yesterday?

The way we talked about Lyd—one from afar, one from close in (and I don’t know which of us is which)—was sad and exciting, and very compelling emotionally and creatively. This time it was not documented—not in literature, nor in a song, nor on camera. This time it will stay between us, with no fly on the wall.

Recommendation: one of Khoury’s conditions for the release of Children of the Ghetto: My Name Is Adam was that the first language it should be translated to had to be Hebrew, so that Jewish readers would be open to our pain. Yehouda Shenhav’s translation makes it feel like Khoury wrote the book in Hebrew. Run and buy the book before it sells out.ii

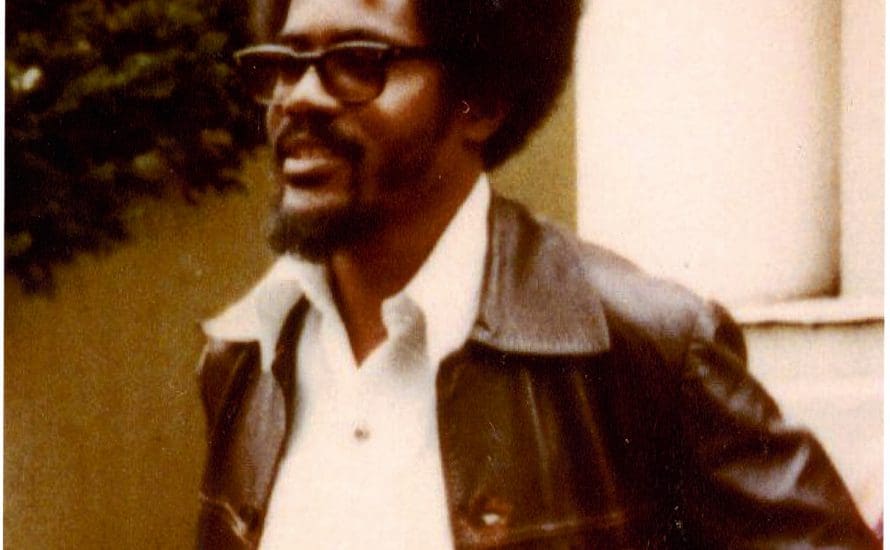

Featured image: still from the trailer for Junction 48, set in Lyd

AntiNote: The day after Antidote editors received this translation, Haaretz published an English version of this op-ed themselves (behind a paywall). Our anonymous translator is happy to have their work appear here nonetheless. And Nafar’s words deserve to reach more people more freely, in our opinion, like they do in his music.

Translator’s notes:

i During the Nakba, Operation Danny was the Israeli campaign to push east from Tel Aviv towards Jerusalem. During the operation, Lyd and Ramle ( الرملة ) were captured, many were massacred by the Israeli forces, and others faced ethnic cleansing and expulsion. This operation was part of a greater project of the Israeli colonial forces to ethnically cleanse Palestinians from the newly-formed Jewish state.

ii In Hebrew, “sale” and “operation” are the same word; this sentence carries a double meaning. One is, Run and buy the book before it is on final sale, but it can also be read as, Run and buy the book before the next assassination operation.