The Black Black Sea

A grassroots effort to save the Black Sea coast in Anapa, Russia

by Svetlana Lomakina (text) and Vigen Avetisyan (photos) (original post in Russian)

translated by the Russian Reader (original post in English)

28 December 2024

“Now It’s Really Black!”

On 15 December 2024, two oil tankers—Volgoneft-212 and Volgoneft-239—were involved in an accident in the Kerch Strait during a storm, and three thousand tons of oil was spilled into the waters of the strait. A day later, the oil washed up on the shores of Krasnodar Territory. Dozens of kilometers of the Black Sea coast were contaminated with mazut (fuel oil), and fish, birds, and dolphins were poisoned and died. Environmentalists have already pronounced the incident a major catastrophe. Local residents, without waiting for marching orders from the authorities, started cleaning up the fuel oil and saving birds and animals from day one. Thousands of people have been going out daily to clean the coastline. Every one of them has their own motivations and their own story connected with the sea.

“We have to do something!”

Marina, Nastya, and the Captain – Jamaica Beach

“It’s really black now! Our poor sea! What have they done to you?!”

Marina leans over a huge jellyfish stuck in an island of oil, and from the way her shoulders are shaking, I can guess that she is crying. Then she pulls back her mask and inhales a breath of the oil vapor-infused cloud. She wipes her tears away and says that she and her husband moved here from Belgorod a few years ago for a quiet life on the warm coast. Before the accident, her heart ached only for her relatives living back home amid the shelling. What is happening here now makes her heart ache as well.

“A friend from Tuapse wrote, ‘Will you put me up? Can I come there to help you too?’” Marina smiles sadly. “They’ve been coming from all over Russia, and many people are hosting the volunteers for free. Many people are feeding them. This is normal.”

The sun sinking into the sea at her back, Marina looks like the heroine of an apocalypse movie—alone, in a protective suit, on an islet of sand surrounded by huge black stains.

They’re black oil slicks. It’s best not to step in them: they will ruin any kind of footwear. But it is impossible not to step into them, because although earlier, when the weather was colder, the fuel oil froze, now, with the temperature at 12 degrees Celsius, it has begun to flow. People armed with shovels are trying to dispose of these spreading stains by bagging them as soon as possible. As will transpire later, plastic bags cannot be used for this job: the fuel oil eats through the plastic and leaks back out. You need special bags—and you need special clothes, respirators, and goggles. They are clumsy to work in, so many people can’t stand it and clean the shore in their street clothes. They regret it later: by the evening their head starts to ache, and when they exhale, it smells like they have a petrol station inside them.

But that is people we are talking about. It is painful to think how marine animals and birds caught in the fuel oil feel. We walk along the shore and gaze into the night in order to save the surviving wildlife. Birds cannot see well at night, which means it is easier to pry them from the oil snares.

Nastya Stolbkova is our chief rescuer. Thirty-four years old, Nastya works as a holiday and tour coordinator. She does her best to publicize Anapa as an underrated region with amazing natural views and protected areas which ordinary tourists can’t reach, including the picturesque Utrish, the Opuk Nature Reserve, and Cape Takil. The accident is thus a personal tragedy for Nastya. She is worried about the environment and the coming tourist season, which now seems an impossibility.

“After the first news reports, I was shocked, then angry: how could they have let it happen?” Nastya says. “But then I realized we have to do something! Friends from different cities wrote to ask what was happening here and how they could help. So I went to Anapa to see it with my own eyes. I sent a video—on the first day, the scenery was shocking—to my friends in Moscow, and they began to raise money through their chats at school and work.

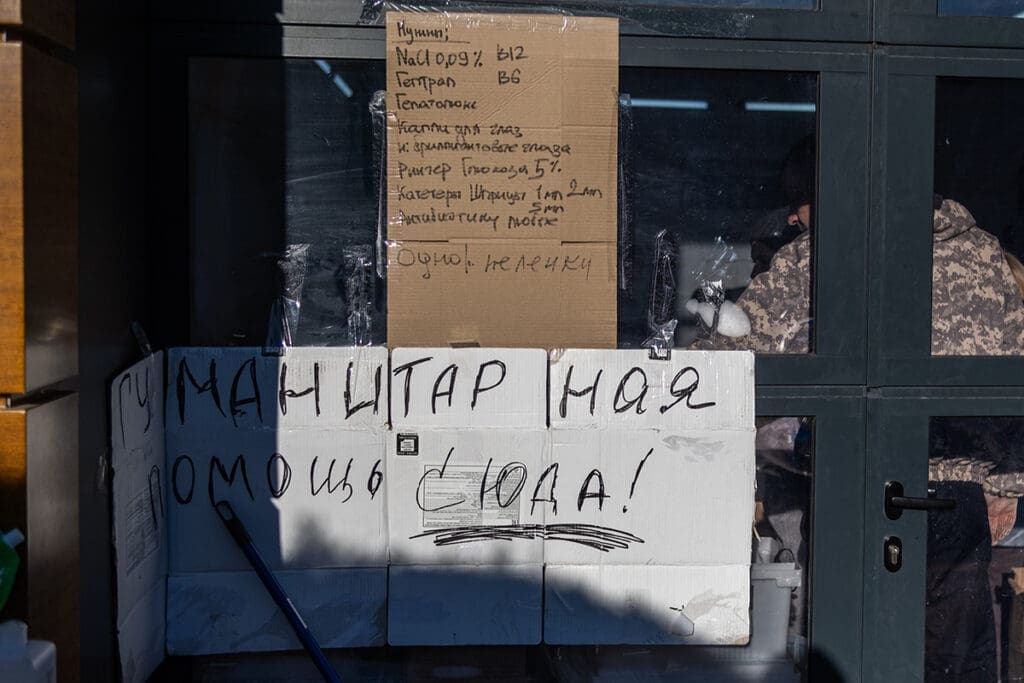

“In a couple of days, they raised a hundred thousand rubles,” Nastya recounts with pride. “The hardest items to get hold of were respirators: they were immediately sold out. Then there were flashlights, protective suits, and wading boots.”

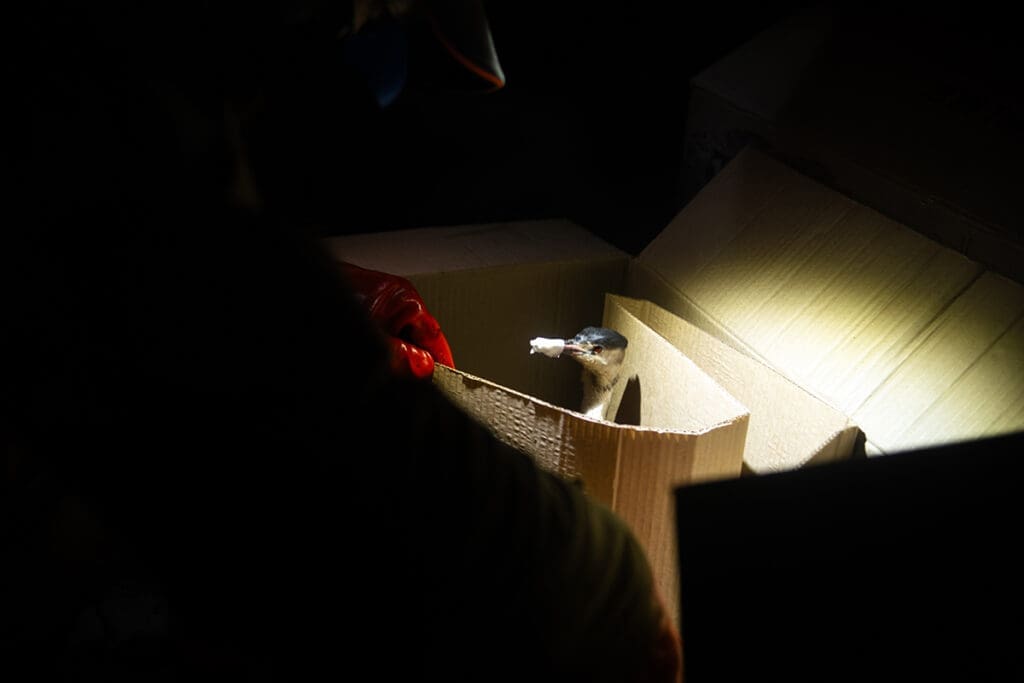

The day before, thanks to just such waders, volunteer Danil Plyushch pulled two birds out of an oil stain floating on the sea. One bird had already given up and was almost motionless, but the other was trying to peck its way through the fuel oil. You could not look at it without shuddering: the bird twitched and stretched but the fuel oil held it firmly in place. Danil went in after it, ultimately pulling both birds out with a net, along with a lump of the fuel oil. The volunteers cleaned their beaks and airways as best they could before putting them in boxes and taking them to a bird rescue center. There were already several such reception centers set up along the coast.

Danil is a yacht captain. The sea gave him a job. From the age of fourteen, he washed boats at the docks and made friends with the locals. He started working as a sailor, and at the age of eighteen he got his maritime license and became a young captain. Now twenty-five, he is already an old salt: he understands the sea, feels its moods, and knows when not to overreact. His assessment of the tragedy’s causes is the same as that of the experts: river tankers should not go to sea in stormy weather, plus there was wear and tear, the human factor, and negligence. And the Black Sea is not an easy one to deal with: it has a southern temperament. You’d think it was calm, when suddenly . . .

Because of these “suddenlys” Captain Plyushch has repeatedly rescued people swept out to sea. Now he is rescuing birds. During the last shift, which spanned the entire day, from morning till late at night, Nastya’s group of volunteers pulled thirteen live birds and one dead bird out of the fuel oil. Help had arrived too late to save the last bird.

* * *

There are a variety of birds. Most common are grebes. Volunteers also come across European shags (one of the rarest birds in Russia), red-throated loons, black-throated loons (also listed in the Red Book), coots, and gulls. There was even one swan at the volunteer rescue center, sitting in the toilet and not letting anyone in.

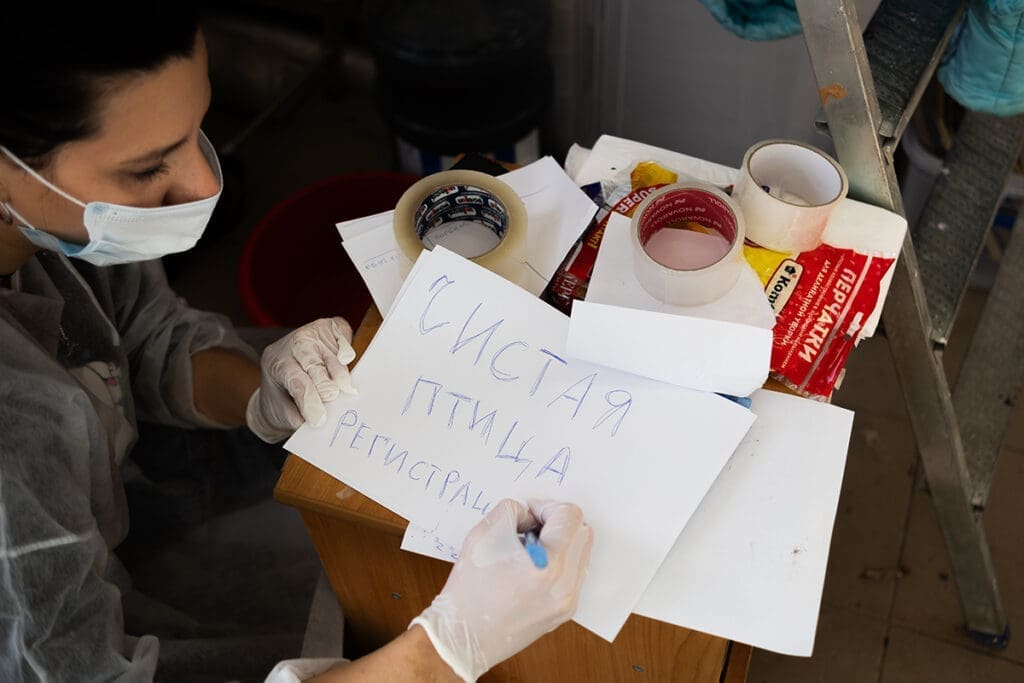

When the birds are found, they are cleaned and their beaks are carefully taped with painter’s tape so that they do not try to clean themselves or consume fuel oil again. At the volunteer bird center, they are registered and recorded: veterinarians assess their condition, make them drink a sorbent, give them medication, and send them off to be washed.

In the center where I worked, in the village of Vityazevo, the birds were cleaned at a car wash, whose proprietor had set aside several bays for that purpose.

The fuel oil is not easy to wash off. First, the bird is lowered into a basin filled with starch and the starch is gently rubbed into the plumage. Each group of washers is supervised by a professional instructor. When the starch mixes with the fuel oil, it turns into a coarse gray meal and crumbles off. Even at this stage, the bird’s suffering is alleviated: it can spread its wings and even get up to a bit of mischief. The latter is a good sign: it means the bird has strength left in it and a good chance of surviving.

After the starching, the bird is moved to another basin, where it is washed with warm water and dishwashing liquid. The work is long and laborious: it takes about an hour and a half on average to clean one bird.

The bird is then bundled up and sent to a rehabilitation center. There is already a whole network of them along the coast: both veterinary clinics and even medical centers have been welcoming the birds. There, the birds are treated and warmed, and when they finally come to their senses, they are released on the water. According to statistics, more than 750 birds were rescued in the Anapa area last week.

One of them was our sneaky little grebe. Before that evening when we wandered along the shore, it had been sitting right by the water for several days: its wings, drenched in fuel oil, were too heavy for it to fly. The bird was going to die a hungry death, but Nastya spotted its tiny silhouette and chased the grebe to the water, where the Captain was already standing in his wading boots. The entire operation took a minute and a half. As luck would have it, a vehicle collecting the birds drove by, and the grebe was dispatched to the veterinarians. The rescuers joked that the bird had been born under a lucky star. Or maybe they had even rescued tomorrow’s lucky bird itself? It just doesn’t look so peachy today, does it?

While we were grunting with laughter in our respirators, a man on a tractor drove up.

“Have you guys seen any dolphins?”

We shook our heads.

“Well, if you see any, I’m here! They’re heavy, you can’t carry them yourself!”

What dolphins?

Veronica – Vysoky Bereg Beach, Anapa

We didn’t find any dolphins that day. But the next day Veronica Kuroglu went looking for them.

Veronica, who is thirty-eight years old, arrived in Anapa from Petrozavodsk on the last train during the pandemic. She had come to stay with her mother. Veronica’s luggage consisted of a single suitcase, a broken heart, and a forestry engineering degree. She had worked for a year as a landscaping specialist at a hotel chain and realized that she could not live without the sea.

She stayed, and soon she met an incredibly handsome man and even married him. “Handsome” is not a figurative expression: Veronica’s guy once worked as a model in China. During the pandemic he moved to Anapa and got a job as a lifeguard. They met when Veronika, who had broken her arm falling off her bike, was unable to open a water bottle.

“All our dates took place here by the water, and the sea is something deeply personal for us. So when the tankers collided, I was emotional, I immediately teared up. I couldn’t work, all my thoughts were out there. I told the owner of the fitness center [where I work], and she immediately went to a builder’s supply store, bought masks and goggles, put a person on the reception desk, and we all went to the beach.”

Veronica is nervous and blushes. She breathlessly recounts how much fuel oil there was on the shore, and how she and her team members clutched their heads and wept before grabbing their shovels and going to clean up the mess. They worked until late at night.

When they got home, everyone felt ill: they realized that even in their PPE they had been poisoned. So they had to split up into smaller groups and work for only a few hours at a time.

By that time, however, the whole city had come to the shore: organizations, housing management offices, communities, and hobby clubs. Even Veronica’s neighbor, a well-known fan of Anapa port wine, was not left out. The trouble united Muslims and Christians, liberals and “vatniks,” janitors and professors. Those who could not go out to the shore—the elderly and children—wove containment booms (ropes mean to prevent the fuel oil from escaping the water and mixing with the sand) in their yards.

Veronica, on the other hand, in addition to cleaning, was on the lookout for dolphins. Cetaceans are her passion. They had always been out there somewhere, in movies and books. But here, on her first day in Anapa, 1 June 2020, sitting on the shore, she suddenly spotted fins in the water. They came closer and closer, and Veronica’s heart beat in rhythm with them. It was no coincidence: pods of dolphins live off Anapa. They approach the shore at the same times in the morning and evening.

The young woman began tracking them, first alone, then with her husband. They bought a standup paddle board and began to swim out to the dolphins, who would let the couple get to within an arm’s length of them. It was incredible.

“But what’s happened now is a disaster. There will be no fish here, the bottom-dwelling crustaceans are unlikely to recover in the near future, and the phytoplankton and zooplankton have also been killed. That means there will be no dolphins either.”

Veronica shows us a photo on her phone of two victims of the oil spill: one small red-billed dolphin, covered in fuel oil, and the other, its species hard to determine by sight. They died long, painful deaths.

Delfa Dolphin Rescue and Research Center reports that eleven dolphins have been found dead in Krasnodar Territory. Six of them had no traces of fuel oil in their bodies, so the causes of their deaths are still unknown. Perhaps the overall contamination of the water had an impact.

Who knows where else these stains are floating in the sea? That is why Veronica walks along Vysoky Bereg Beach on her days off and climbs into the most inaccessible places, hoping to find a dolphin that can still be saved—because dolphins, unlike humans, did nothing to cause this tragedy.

“It’s alive!”

Valentina Vysotskaya – Blagoveshchenskaya

While the work is going on ashore, many volunteers recall the 11 November 2007 tragedy in the Kerch Strait: four dry cargo ships and a tanker sank during a storm. Two thousand tons of fuel oil spilled into the sea. Eight people died, and the entire shoreline was strewn with dead animals and birds.

“Back then it was not talked about a lot, there was not such good internet,” recalls Valentina Vysotskaya. “But now I have a ‘radio’ on my phone, and we find out everything. As soon as it became clear what had happened, we went to our shore.”

Valentina lives in the village of Blagoveshchenskaya. It is the most beautiful spot in the area, a place where the Black Sea and the Kiziltash and Vityazevo limans meet. The locals like to relax there, as do a special set of out-of-town holidaymakers, fans of silence and bonding with nature.

“This is Dad’s gift to us, his children and grandchildren. Dad would have been one hundred years old this year, and the cottage I live in is 120 years old. It’s made of clay, one of the first ones on the shore. I am constantly adding to it, reinforcing it, so that it lasts longer.”

Valentina blushes for some reason, embarrassed.

Her father, Ivan, had been the oldest child in a large family. Ivan was sixteen when his own father was drafted to the front and soon went missing in action. The teenager took on the older man’s responsibilities: he fixed everything at home, minded the younger ones, and got a job early. He was a miner in Donetsk Region. All his life he supported his sisters and brothers, and was especially happy for the youngest, who served in the navy.

When his brother’s letters from yet another distant harbor arrived, Ivan would reread them several times, imagining that he could hear the roar of the sea in the pages of the letter. Later, he confessed that if it hadn’t been for the war and his difficult life, he would have definitely become a sailor.

The dream was on his mind his entire life, so when Ivan retired, he announced at a family meeting that he was done: he was a free man, his children had grown up, and he was going to look for a new house by the blue sea.

Ivan enlisted his eldest daughter, Valentina, as his wingman. She was already an adult, and even had children herself, but for the sake of the search left her family behind. In Novorossiysk, they boarded a train and traveled literally wherever their hearts desired: everywhere was good, but nowhere felt like “home.” Only in Batumi, in the mountains, did they find an inexpensive house close to the sea. They had almost made a deal with the owners when Ivan changed his mind. “No, I cannot live without understanding what people say behind my back,” he said. Once more, they traveled and traveled before arriving in Anapa, were they were advised to look at an inexpensive village near a statе-owned vineyard. At the time, in the late seventies, the village was unpopular, although there was a fishery, fertile land, and a huge sea that seemed to hug the settlement.

They stayed put in Blagoveshchenskaya. Ivan, a handy man, began to renovate their new home. Construction materials were scarce at that time, and the family did not have much money, but every storm cast sound, salted planks ashore. Ivan would tie them to his bicycle and take them home: some of them came in handy there, while he took the others to school. He worked as a shop teacher then. He made wonderful things from the boards and passed the skill on to the kids, and the kids loved him.

Valentina inherited her father’s talents as a teacher and his handiness. For twenty-three years she lived and worked as a kindergarten teacher in Usinsk, in the north. Every year she would send her four children to Anapa for summer holiday, and in the autumn she would bring home whole suitcases of driftwood scraped clean by the sea. She would adorn them with northern natural materials and take them to the kindergarten. In her classes, she taught the kids to make pictures from sea pebbles and hear the roar of the sea in seashells.

“It is alive. Here you are standing on the shore, and the wave seems to be far away, but it sees you, and now it is near. It runs toward you, it senses you. But I tested it. There are droplets of oil in the water now, and it’s different.”

On the day when everyone went out to clean up the fuel oil from the shore, Valentina, who is sixty-nine years old, at first tried to remove the soiled bits with a shovel, but the fuel oil inconveniently got mixed up with the sand. She began to dig with a spade, and then with her hands: she could feel it when she would get a chunk of black “slime” in her hands. This was how her children, grandchildren, and neighbors cleaned the beach three days in a row.

A few days later, when the sacks of dirty sand grew on the shore and the surrounding area had become shinier and cleaner, there was hope that people would clean up the entire mess and the sea, sick and wounded though it was, would pull through. Valentina again recalls the tragedy of 2007, and hopes that they will pull through this time too. But conclusions have to be drawn and mistakes corrected.

* * *

Ecologist, soil scientist and hydrologist Anastasia Ligay argues that what has happened has already caused serious damage to the natural environment, but that is not the end of the story.

“Per the GOST standards, sand contaminated with oil products must be removed from the beach in sealed steel containers. The equipment [sic] arrived, and the containers should be stacked on it and taken to the landfill. There is no official landfill for such waste in Krasnodar Territory. At the moment, everything is being taken to Bely Hamlet. Vehicles are queuing there, and the local residents have been complaining.

“The tractor that picks up the oozing bags also drags fuel oil over the beach by lifting up the layers and mixing the oil with the sand. The right thing to do would be to remove all the sand down to the bone, dispose of it as third-degree hazardous waste, and bring in new sand.

“The issue of liquid wastes — everything left over from washing the birds — has not been solved either. They are being stored in barrels for the time being. Plus, the overalls and PPE should be disposed separately.

“Our working group from the Russian Ecological Society (REO) is scheduled to visit the site on 25–27 December. We will take samples and make forecasts about what will happen to the food supply and, consequently, with the fish catch and marine animals.”

The experts have huge reservations about the tourist season. But we still have to live to see that day, since last night there was a storm; some of the bags which had not been removed in time were damaged, and fuel oil leaked back out. Plus, the fuel oil stains have washed further out to sea, toward Crimea, so there is still more than enough work to be done.

Note from the Russian Reader: I have edited the photo reportage by condensing some photos into “galleries” and cutting out others to make this post slightly easier for my readers to digest, but I would encourage you to follow the link to the original publication, where you can peruse Vigen Avetisyan’s grim but stunning photos as they were meant to be seen—full-size and with all their captions intact.

And from us at Antidote: We removed most hyperlinks from the original—the Russian Reader is assiduous about putting background information and citations at readers’ fingertips, including cultural and linguistic references that amuse as well as inform. We invite you to look up “tomorrow’s lucky bird,” linked in the original, just as one example. And as always, check out the rest of their stuff and help spread this precious and dearly crafted resource around.