The Partisan from Ryazan

by Anna Jikhareva for Die Wochenzeitung (Switzerland)

5 June 2025 (original post in German)

First, Russian anarchist Ruslan Sidiki attacked a military airbase. Then he derailed a freight train. The story of someone who risked everything for his principles—reconstructed from prison writings, personal accounts, and court records.

Prologue

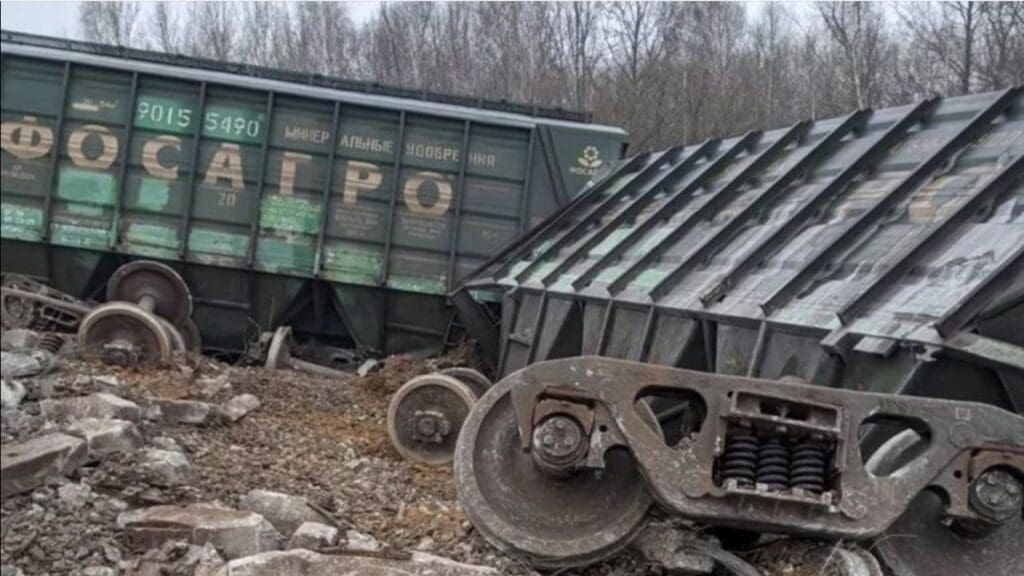

11 November 2023: It’s early in the morning on a cold day when a loud boom resounds through the forest near the Russian city of Ryazan. Between the Rybnoye station and a checkpoint, nineteen of freight train #2018’s fifty-four carriages are derailed. Its cargo—a mineral concentrate called apatite, used for fertilizer—was on the way from the far north to Saratov Oblast on the border with Kazakhstan. In a press release about the incident, the state rail company speaks of “external causes.”

Both people on board, the conductor and his assistant, suffer light injuries from their cabin window bursting in the shockwave. Authorities later estimate the damage totals at around $300,000 for the rail company and around $8,400 for others affected. They classify the incident in the forest as a terrorist attack.

A few hours beforehand, on Internatsionalnaya Street, Ryazan: in a faceless apartment building on the edge of town, Ruslan Sidiki gets ready. He puts explosives in his backpack, along with a change of clothes, then he gets on his bike and rides off to a spot where trains with war materiel pass through on the way to the Ukrainian border.

“Rail infrastructure is the circulation system of a country at war. […] In my research I discovered one of the arteries goes around Ryazan to points south—trains with military hardware. A little scouting and I could confirm how frequently the trains go through, and that the route is only used for freight. I decided this was an appropriate target, and all you’d have to do to destroy this transport line is blow up the tracks.

“This act of sabotage cost me less than 10,000 rubles [around $100]. Within a few days, I’d built two powerful bombs and a video camera with a self-destruct mechanism. I went over the escape route in my head. I had night vision goggles, and packets of pepper in my pockets to confuse the dogs. At midnight I arrived at the spot, set the explosives under the tracks, and placed the camera in a tree where it could register the moment of the explosion. I scattered the pepper where I had hidden. […] As it started getting lighter and the image on the camera became visible, I waited for the right moment, made sure it wasn’t a passenger train, and hit the ignition. […] I saw the effects of the rail explosion on the news.”

Ruslan Sidiki is a self-described anarchist. Two weeks ago, the thirty-seven-year-old was sentenced by a military court to twenty-nine years for “terrorism”—the saboteur will spend nine of these in a prison, and the other twenty in a penal colony. He does not deny that he derailed the freight train. He also admits to a second act: a drone attack on a nearby military airbase a couple months prior. But Sidiki won’t speak of terrorism; his goal was not to cause fear and shock in the population, he says, but to impede Russia’s war effort in Ukraine.

Ruslan Sidiki’s case is special in many ways, above all because he—in contrast to other militant activists—keeps the public informed about his way of life, his motivations, and much more, including his ideological commitments, thereby keeping control of his own narrative. In most similar cases, only the representations of the FSB, Russian domestic intelligence, are available—either invented out of whole cloth or forced from the mouth of the accused under torture.

Most of the quotes in this text come from letters Sidiki wrote from pretrial detention and that the human rights activist Ivan Astashin provided WOZ—some of them exclusive. The rest of the information is taken from investigation and prosecution files obtained by WOZ, examinations in court, and reports from Russian independent media sources.

“Did I feel like a partisan? I think you could describe it that way. If people resisting the Third Reich on its own territory during the Second World War were called partisans, then I count myself among them.”

“I think resistance against totalitarian regimes is the duty and right of every person.”

“The Russian government has eliminated every possibility of influencing the situation peacefully. Anyone who speaks out against the war is declared a traitor and faces repression. In such a situation it is no wonder some leave the country, while others turn to explosives.”

“PS: I think the impossibility of peaceful and lawful resistance against the actions of rulers leads to people showing up who are ready for more radical acts.”

I. Industry and Country Air

Ruslan Kasemovich Sidiki was born on 16 March 1988 in the city of Ryazan, two hundred kilometers southeast of Moscow. He was raised by his mother and grandmother; his father is from Afghanistan, came to Ryazan for military training, and went back to Kabul when Ruslan was still a child. In chaotic 1990s Russia, Sidiki’s life was shaped by a gloomy, harsh reality: the war in Chechnya is getting wall-to-wall coverage on TV, the people around him are “sullen and aggressive.” Sidiki remembers how his neighbors guarded their front doors “so no one could plant mines in the basement.”

In 1999, a series of apartment complex bombings caused hundreds of deaths and injuries; the authorities blamed “Chechen separatists”—evidence points, however, to the participation of the FSB. The attacks gave the Russian leadership a pretext for starting the second Chechen war. In the process, a previously unknown former intelligence officer rose to the presidency: Vladimir Putin.

“It was a typical childhood in the industrial zones of the nineties. All around us were construction sites, ruins, and garbage dumps that became our playgrounds. We didn’t grow up well; we spent a lot of time on the streets because there was nothing to do at home. It was way more fun to run away from construction site security guards, to throw balloons in the fire and wait for the pop, to explore the subterranean, to build shelters out of tree limbs and straw. Mechanical and electronic devices were interests of mine early on too, so my parents bought me science books and model kits.”

When he was eleven, the boy spent the summer with his mother, who had in the meantime gone to live with her new partner in Sicily. When she broke the news to him that he would be living with her from then on, a carefree vacation suddenly became a whole life turn. It took months for Sidiki to get used to his new surroundings. By the end of the school year, when he was starting to get the hang of the language and was finding playmates, the situation got better. Missing his grandmother and his friends, he would go back to Ryazan on summer vacations.

After finishing secondary school, he apparently attempted to join the Comando Truppe Alpine, the mountain troops of the Italian army.

“Back then I believed way more in the possibility of social revolution, life without the state. Not that I don’t believe in it anymore, I’ve just gotten to the bottom of things, and understand that it’s not so simple and not everyone is suited to it. I don’t see any contradiction between anarchism and joining the army of a country not at war, limited to one year and without further obligation. […] In the Italian army I could have had the chance to gain knowledge and skills around weapons, equipment, and technology.”

This passion for technology, including illegal devices, is a throughline in everything we know about Sidiki’s life. During his time in Italy, he was already interested in explosives, he recalls: he saw instructions for a bomb in a newspaper report, and would build one just like it years later. He stayed a while longer in Sicily after being rejected by the army, but when he was offered a job as an electrician on a visit to Ryazan in 2008, he turned his back on Italy. He longed for his grandmother and his childhood friends, Sidiki wrote later, and was bored by the prospect of a quiet life in Europe.

II. “Stalking” Restricted Areas

“From 2009 on, I was really into illegal hikes in the exclusion zone around Chernobyl in Ukraine and Belarus. I showed other people around there too—not for money, but to have some company. That’s how I got to know a few Russian and Ukrainian comrades.”

One of these comrades was Pyotr Volin (not his actual name). Volin got to know Sidiki by way of a mutual friend, he tells me one evening over the phone. “We wrote back and forth all winter, then met at a train station in Moscow, bought tickets to Kyiv, and two days later we were walking around the exclusion zone, where we spent an entire month.” The friendship that developed during that time continues today.

Until Russia’s annexation of Crimea, Sidiki would travel to the exclusion zone yearly. His interest had been piqued by the first-person shooter game “Stalker,” which is set in the zone around the nuclear plant infamous worldwide for its reactor meltdown. The game, in turn, is reminiscent of the seventies-era science fiction film of the same name by the influential Soviet director Andrei Tarkovsky, in which the protagonist has to come to terms with a likewise mysterious zone.

Sidiki also sees himself as such a “stalker,” in survival mode. He would set out on illegal trails, no GPS but equipped with old army maps instead; he set up camp in ruined structures, listening to the wolves at night.

“I played partisan. The forest, a backpack—and the aim of getting where I was going without being caught.”

“When I salvaged gadgets as a kid, my mother scolded me because she feared they might be radioactive. She also told me of a city where residents had to leave because of the nuclear disaster. Household appliances from there kept turning up and would contaminate their surroundings. The fact that travel to the exclusion zone was forbidden made it even more appealing to me. I like to bushwhack through hard-to-reach places.”

After the annexation of Crimea, many friendships broke down in Russia—even among leftists there were those who supported the aggression. Sidiki decided to live in an eco-anarchist commune; from that point on he would spend summers at “New Way,” a collection of dwellings inhabited by fellow travelers in a forest near the village of Bochevo, a few hundred kilometers southeast of St. Petersburg. He planted a vegetable garden, built a clapboard house and wired it himself, and took long bike rides across the countryside. “Ruslan was really interested in autonomous places and anarchist living methods,” recalls Volin. Together they were part of a movement that encompassed over fifty autonomous communal projects at its height.

Volin has only positive things to say about his friend. “Ruslan could be somewhat introverted, more of a loner, but he is a deeply kind and decent person, who was never indifferent to the suffering of others—someone you could always count on.” Sidiki’s survivor’s spirit and his varied interests fascinated Volin: electronics and agriculture, physics and chemistry. “He was very talented, and always went about his business in a really serious way. Everything he touched would work out somehow,” Volin says.

“I understand anarchism as a way to help or participate in projects, wherever possible, adjacent to the movement; taking part in actions aimed at protecting the rights and freedoms of working people; bringing people in contact with particular ideas when conditions allow; acquiring new skills and knowledge in order to do all of the above more effectively.”

III. War on War

On 24 February 2022, Sidiki nodded off on a train from Ryazan to Moscow; he heard snippets of conversation among other passengers as if dreaming: “We’ll be in Kyiv by this evening” – “They were going to attack us.” Scrolling through newsfeeds when he awoke, he saw his fears confirmed: the full invasion of Ukraine had begun. It was an extremely uncomfortable feeling, recalls Sidiki in a letter from prison: “You see the carriages full of military hardware rolling past, and you can’t do anything.”

A couple weeks later he wrote a friend in Ukraine who he knew from his “Stalker” days. He said he was considering joining the Ukrainian army, but let it drop since he had no training as a soldier. The friend, who took part in the defense of his country, would later die in an offensive near Kharkiv. The Russian invasion of Ukraine was a “personal tragedy” for Ruslan, recalls Volin.

“I decided to try to impact the situation in a militant way towards the end of 2022, as it became clear the war would go on a long time. The Russian army was attacking Ukrainian energy infrastructure without concealing its intentions: to deprive the civilian population of water, heating, and electricity so the people, exhausted, would pressure their government to give up. Article 205 of the Russian Federation’s criminal code [the terrorism statute] speaks of ‘bombings and other activities intended to intimidate a population.’ The activities of the Russian side fall precisely under this definition.”

“The attacks on Ukraine coincided with the noise of long-range bombers outside my window. That was the reason I chose the Dyagilevo airbase as my first target; it wasn’t more than ten kilometers away from my house.”

Thanks to his passion for technology, Sidiki owned a homemade quadcopter. As he would later recount to investigators, he contacted a Ukrainian friend who would in turn put him in touch with a representative of military intelligence. In February 2023, the self-declared partisan would meet this person in Istanbul, where he—to ensure that he wasn’t working for the FSB—had to pass a lie detector test; later he would fly on to Riga. There he was allegedly trained by Ukrainian intelligence in sabotage, according to Russian authorities—Sidiki denies this, insisting that everything he needed to know about sabotage, he taught himself. He also claims to have later turned down an offer of a large sum of money. He maintained contacts in Ukraine after his return to Ryazan.

On 20 July 2023, Sidiki conducted his first operation: the attack on the nearby Dyagilevo airbase. Overnight he had outfitted four quadcopters with homemade explosives. He brought the drones outside the city, programmed them for the impending mission, and returned home. As Sidiki would later learn from the news, only one quadcopter actually worked. No one was injured in the attack, and no fighter jets were damaged. For weeks afterward, he would listen anxiously at the door whenever anyone passed by, Sidiki recalls. When nothing seemed to be happening, he started to relax again, but was annoyed that the mission hadn’t gone according to plan.

A few months later came a fateful blow: in early October, Sidiki’s elderly grandmother, with whom he had been very close his whole life, died. He knew that grief was making him careless, but resolved nonetheless to resume his activities. “The war continued, and since my attack from the air had failed, I thought I’d better try something on the ground.” So Ruslan Sidiki set his sights on rail infrastructure.

IV. Crime and Punishment

On 29 November 2023, Ruslan Sidiki was arrested near his home. It appears from court records that police had nothing on Sidiki at the time. He would later report to his attorney that he was tortured in the first days of his detention.

“Searching my phone, they determined from my Telegram channel subscriptions that I was at the very least not a supporter of the so-called ‘special military operation.’ That’s another mistake, I admit: you’ve got to look like a normal turbo-patriot online. Knowledge of your rights under arrest—not to mention of their methods—also wouldn’t hurt. When they were beating the information out of me, one of them said: ‘…and to think I wanted to pull up every cyclist in Ryazan!’”

“At the police station, they said they would get the information they needed either way; they threatened to take me to the wilderness, torture me, shoot me, and set it up to look like I tried to escape. Then they asked me if I had any chronic illnesses. When I said no, I took a punch to the head and fell to the ground, and they started kicking me. Then they wrapped cables around my feet and started torturing me with electric shocks.”

When Sidiki entered pre-trial detention, signs of torture on his body were confirmed by a doctor: wounds on his head, burns and bruises. He submitted a complaint that was never looked into. He describes the time that followed as “extremely difficult;” thoughts of suicide plagued him. The sympathy of friends and acquaintances gave him some hope, as well as the many letters from strangers that he received in prison.

On 13 February 2025, the trial against Ruslan Sidiki began under the auspices of a judge of the second western district military court. He was made to take his seat in a cage, with chains on his wrists and ankles.

Investigators classified the attacks on the airbase and the railroad as acts of terror (pursuant to article 205 of the Russian Federation’s criminal code). They also accused the anarchist of preparing a third attack: an additional railroad bombing in January 2024. They regarded the preparations for both acts of sabotage as “training with intent to commit an act of terror” (article 205.3), and added the charge of having manufactured and deployed explosives “in an organized group” (articles 222.1 and 223.1). The investigators alleged he was recruited by Ukrainian military intelligence.

Sidiki admits to both acts of sabotage, but denies preparing a third, and maintains he worked alone. He also doesn’t want his actions classified as terrorism. In his final statement in court, he apologized to the workers who suffered light injuries in the train derailment. After once again explaining what motivated his actions, he recited the words of Ukrainian anarchist Nestor Makhno, who had built anarchist social structures in southern Ukraine during the Russian civil war starting in 1917.

On 23 May, the court handed down its sentence. The judge took one year off the thirty requested by prosecutors.

Epilogue

Ruslan Sidiki is currently sitting in prison in Ryazan. Since being sentenced, he hasn’t spoken with his attorney Igor Popovsky, the latter told me by phone. Popovsky finds the punishment “excessively harsh, even by the current standards of the Russian regime.” In order to intimidate the population, he says, sentences keep getting higher and higher for resistance to state power.

According to the anti-authoritarian initiative Solidarity Zone, over three hundred militant acts were taken in Russia and the occupied regions of Ukraine in the first nineteen months of the full invasion—most of them acts of sabotage against rail infrastructure and attacks on military enlistment offices and other nodes of state machinery. Since then there have been many more.

“I think you can count me as a prisoner of war, because my actions took place in the context of the war between Russia and Ukraine. I would be a political prisoner if I had landed behind bars for a peaceful protest against the war. My activities fall under the term ‘sabotage,’ but certainly not ‘terrorism,’ because my goal was not to instill fear and shock in the civilian population. The goal was to destroy airplanes so that they don’t have anything to drop bombs with; to destroy the ways forward so they can’t advance.”

“Some say not to fight for Ukraine, because you’d be de facto fighting for the interests of a few politicians and companies. Sure, that could be partly true. But when you start from the fact that no one attacked Russia, and it is the aggressor, and it won’t stop—every concession simply increases its appetite—then Ukrainians can either quietly put their heads down and become part of the Russian Federation, or they can resist. I think that in such a situation, offering a helping hand is a noble act.”

Popovsky says he expects to receive the court’s written judgment this week. He then wants to appeal the case to the supreme court. He bases his argument that Ruslan Sidiki is a prisoner of war on the indictment itself. “If they are saying he was recruited by Ukrainian intelligence, then under the Geneva Conventions he must be classified as a combatant.” Sidiki’s Italian citizenship could also help him gain freedom. Two officials from the Italian consulate in Russia were present in the courtroom for the sentencing.

Translated by Antidote

Featured image source: Mediazona via WOZ