AntiNote: This unauthorized republication of rarified material is presented in a spirit of well-meaning autonomy and solidarity. We think you will appreciate why this work deserves to be free and widely available.

We have preserved original links to sources and references, and added a couple of our own for good measure.

Genocide in Syria, Gaza, and Beyond

An interview with Yassin al-Haj Saleh

by Wendy Pearlman for the Journal of Genocide Research

4 July 2025 (original post [paywalled] on Taylor & Francis Online)

Note from the Journal of Genocide Research: Yassin al-Haj Saleh is a Syrian intellectual, dissident, and the author of nine books, including The Impossible Revolution: Making Sense of the Syrian Tragedy (London: Hurst Publishers, 2017). Arrested as a nineteen-year-old medical student due to his political affiliation, he spent more than sixteen years in prison. Upon his release, he completed his medical studies and became one of Syria’s leading writers and thinkers.

Al-Haj Saleh has lived in exile since 2013 and is currently based in Berlin. He has written for outlets such as the New York Times and New York Review of Books, and is a regular contributor to the Arabic daily Al-Quds Al-Arabi, the German magazine medico international, and the Syrian online periodical Al-Jumhuriya, which he co-founded.

Al-Haj Saleh’s wide-ranging work theorizes and analyzes issues related to state violence, struggles for liberation, culture, contemporary Islam and Islamism, and Syrian affairs, among other topics. His recent writings increasingly engage genocide studies, offering critical insight into the concept of genocide in both theory and empirical application. This work also extends to thinking about genocide to craft new vocabularies and frameworks for understanding the varied forms and functions of political violence, including through the development of original concepts such as “genocracy.”

Wendy Pearlman, a professor of political science at Northwestern University, asked al-Haj Saleh to reflect on genocide in Syria, Palestine, and the Middle East; to discuss his innovative conceptual contributions; and to apply this analytical apparatus to help us make sense of developments in Syria since the collapse of the regime of Bashar al-Assad in December 2024.

Wendy Pearlman: Historically, few scholars and intellectuals of the Arab Middle East have focused on the topic of genocide. What brought you to this topic?

Yassin al-Haj Saleh: What brought me to this topic is Syria, the long Syrian struggle.

Israelis, for understandable reasons, have studied genocides, and the Holocaust in particular. Few Arab academics and intellectuals have shown interest in this field of research. However, I discovered that genocide and genocidal massacres are quite interested in us Syrians, Palestinians, and peoples of the Middle East.

There has been a wide area of convergence in the Middle East between exterminatory violence and communal-centered politics. This calls upon us to think about the applicability of the category of genocide to study struggles in the region, and especially the Syrian struggle. In thinking about genocide, my purpose was not to determine whether or not a genocide was being perpetrated. Rather I found in the genocide literature helpful tools and insights with which to talk about the complex Syrian conflict. You can say that I developed an interest in this field for pedagogical reasons. The field offers a whole family of useful concepts, of which the concept of genocide is the oldest.

The issue for me is extreme violence, a theme that is generally absent from the leftist intellectual tradition to which I belong. Our thought focuses on exploitation, or maybe on discrimination and hierarchies, but not on mass murders and massacres. You repeatedly find people from the left condemning manipulators but keeping silent on murderers. That is especially the case when the latter adopt anti-colonial language, regardless of how dull and insincere it is. This habitus was unacceptable for me. It has been complicit in major crimes, if not guilty of explicitly supporting the perpetrators.

A concept that I found quite enlightening for Syria is “politicide,” coined by Barbara Harff and Ted Gurr in 1988.i They observed that the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide mentions that genocide is committed against national, ethnic, racial, and religious groups, but does not mention political ones. Harff and Gurr give the example of the Indonesian Communist Party, which saw close to one million members murdered by the Suharto regime. The Communists were killed because of their political positions and social role.

By contrast, I use “politicide” to denote something different: not physically killing people for their politics, but rather killing them politically. This is true in Syria for all the independent parties in which I was a member. We were killed as parties, be it through torture, long years in prison, the targeting of our families, or making our lives exceedingly difficult. Islamists, on the other hand, faced politicide in the original sense of the term: being murdered as a political group.

Here, a nagging question can be raised: when we talk about Islamists, are we talking about a political or a religious group? The boundaries are rather blurred. This resonates with my work on sectarianism, where I discuss how “groups”—in the Syrian context, sects—are politically manufactured from raw social material that might have taken other forms. I do not believe that groups are natural in any context. Identities are social and political constructs. And that is what is missed in uncritical usage of the concept of genocide, which supposes that fully self-encapsulating groups exist before genocidal processes come underway.

So, as you see, I found the family of concepts related to genocide to be quite useful. Recognizing my debt to this literature, I also tried to coin a new term: “speicide,” which means murder of hope. I believe this captures one dimension of a real experience in Syria: the mass murder of hope for millions, over more than a decade.

WP: Many observers in the West have viewed Syria through the lens of “civil war” rather than genocide. Why do you think genocide is a fitting lens for understanding Syria? Why, in your view, don’t more commentators on Syria see it?

YHS: Many observers in the West lack knowledge and feeling. You read, “The Syrian civil war began in March 2011.” This sentence deserves the award for the laziest and most stupid sentence ever written about Syria. What started in March was a peaceful popular uprising, which faced overwhelming violence from the regime from the very start. The right word for this is brutal oppression. When people started to carry arms, the regime escalated to massacres and sectarian massacres.

You can legitimately talk about a Syrian civil war between fall 2011 and July 2012, when the national setting of the struggle started to crumble. But even in this period, I think it is debatable to speak about civil war in Syria without some qualifications. It is undeniable that we had civil strife after the militarization of our struggle. But was that a “war”?

Based on the Syrian experience after the revolution, I discriminate between three types of violence. The first is war, which is something that occurs between equals, whether they are states, armies, gangs, and tribes. The second is the violence of the weak against the powerful, which is usually called “terror.” The third is the violence that a powerful party inflicts on a far weaker one, and the proper word for this is not war, but torture. Belonging to this last variety are colonial wars, slavery, the “War on Terror,” and the “wars” of thuggish regimes against rebellious sectors of their population—like what we had in Syria.

In other words, using the term civil “war” in the Syrian context is as innocent as using the term “war” to name the Israeli genocide in Gaza. And it is likewise just as biased and as lazy. These same people kept talking about civil war in Syria even when we had the United States, Russia, Turkey, Israel, and Iran and its satellites occupying Syrian lands and killing Syrian people. They continued using the term “civil war” even when many non-state actors from neighboring countries were involved in our struggle. Instead of trying to come up with new ideas to name this rare situation, they kept reiterating the same old term.

I recommend that we talk about torturous wars in the two examples of Syria and Palestine. If there was a genocide in Srebrenica, why is it not a genocide in Gaza? Or before that, in Syria?

I do not insist upon the term of genocide, and I do think there should always be nuances and qualifications when we use it. But beyond ignoring the huge imbalance of power between the two alleged warring sides, calling what took place in Syria between March 2011 and December 2024 a civil war erases the enormous ruptures that occurred during that long period. It renders the term akin to a dark night where all cows appear black, to invoke the German proverb used by Hegel when commenting on Schelling’s undifferentiated notion of the absolute.

WP: In your article in this journal, “Anatomy of Tadamon Massacre, Damascus, 2013” (vol. 16, no. 2, 2024), you suggest that we explore how “to use the concept of genocide to illuminate the Syrian situation, and to use the Syrian experience to criticize the concept of genocide.”

Tell us more about what insight can be yielded on both tracks. That is, what aspects of the Syrian experience can the notion of “genocide” help us understand that a focus on other forms of violence cannot? And how can the Syrian experience complicate, challenge, or advance conventional understandings of genocide?

YHS: The concept of genocide brings together exterminatory violence and activated communities, which is a combination that we had and still have in Syria. However, the concept also entails other elements, such as intent and the idea that the only victims are “innocent” victims, killed for who they are and not for what they did.

These elements can and should be approached critically. I spoke earlier about torturous war, which entails torture more than war. If we take this into serious consideration, it relates to the question of victims’ innocence. People resisted and were forced to resist, but they were still practically unarmed societies due to the large gap in the quantity and quality of arms between the two sides. When the “state” and its protectors monopolize warplanes, chemical weapons, barrel bombs, phosphorus munitions, scud missiles, and so on, are we really talking about war and civil war?

As for genocidal intent, can we not deduce this from the regime’s recurrent statements and especially its slogans? Take, for instance, eternity (abad), which was the millenarian term used by the regime to imply that it would stay in power forever. By the way, abad is etymologically related to ibada (annihilation) in such a way that suggests abad cannot be achieved without ibada. Abad is not a smooth continuity, but a torturous way to preserve what Dirk Moses calls “permanent security.”ii

Other slogans, such as “Assad or no one,” or “Assad or we burn down the country,” or “starve or kneel” (all of which rhyme in Arabic), share an absolutist, nihilist structure. The absolute negates the relative and the partial, which is politics. Our absolutist regime was negating the whole of Syrian society. No wonder the extremist Islamists emerged to confront that formulation. They are absolutists themselves and thus were naturally selected as the “objective opposition” in this unpolitical polity called Assad’s Syria.

WP: In the past year and a half, the question of genocide has also come front and center in Gaza. How do you make sense of genocidal violence in Gaza, and the world’s response or non-response to it, from your perspective having thought so much about genocidal violence in Syria?

YHS: Raz Segal, the Israeli genocide scholar, called Gaza a textbook case of genocide. The Western media and governments insist that it is a war, and one instigated by Hamas’s assault on Israeli targets on 7 October 2023. The people who attribute Israel’s carnage to 7 October, like many here in Germany, are oblivious to how this pseudo-historical explanation is contradictory. If 7 October is the context of the genocide in Gaza, why are seventy-five years of colonial dispossession, racism, siege, and aggression not the context of 7 October? Selective contextualization is as predominant in the West as selective solidarity.iii

For me, Gaza is the paramount example of torturous war, an aggression that has been torturing 2.3 million people for nearly twenty months as of this writing, and with many similarities with Syria.iv A power monopolizes destructive weapons, has unlimited resources from Western powers, has been destroying Palestinian lives in Gaza (and the West Bank) for more than five hundred days. In Syria, it went on for five thousand days and with more than half a million victims. Israel is as productive of death as was Assad’s Syria.

These two powers are obsessed with eternity, permanent security, and supremacy. They both play (or played) the card of the “War on Terror,” which the United States has diagnosed as the fundamental global political evil since the 1990s. This diagnosis made Islamists the global villain (it was Communists when I was young and a Communist) and made security (rather than freedom, justice, or democracy) the global good. It also rendered genocides invisible. Within this perspective, Bashar became a viable partner. I believe that, if his regime had not been toppled swiftly in twelve days last year, the United States would have found ways to reproduce the bloody stagnant status quo in Syria.

Israel and Assad’s Syria also share the idea of viewing any threats against them as existential and maintaining that the only response is to refuse political solutions and instead wage an existential war, meaning a nihilist one. Genocide is always present when your worldview is grounded in existentialisms.

I think that the Assad regime created possibilities for Israel that did not previously exist. One can talk about the Syrianization of the Palestinian people at the hands of Zionists after the Palestinization of the Syrian people at the hands of Assadists. The structure is one, and it is exterminatory.

WP: Many of your writings theorize violence as a technology of political power and domination. In that context, you have coined the term “genocracy.” What is genocracy and what does that term uniquely capture?

YHS: I came to coin this term after thinking over issues of genocide, and especially the dimensions of intent and preexisting group identity, with which I never felt comfortable. I was seeking to denote the preexisting condition that enables genocides or their infrastructure.

Genocracy is the rule of the genos, which in Greek refers to race, dynasty, or tribe. It captures the idea of “national, ethnic, racial, and religious groups” in the aforementioned UN convention. The genos can be a majority or a minority, but it always stands opposed to the demos. The demos divides people on horizontal rather than vertical lines. Genos-centered movements and governments undo the demos and, through this, render democracy impossible.

Genocratic politics are on the rise globally; among genocracies are white supremacy in the US, rightwing populism in Europe, Hindutva in India, Islamism in the Muslim world, and Zionism (and, through the latter, there are many “democratic” proxies in the West of an essentially genocratic polity). I see the US under Donald Trump as a popular genocracy, oriented towards making whites unquestionably dominant again. India and Israel also fall squarely in this category of popular genocracies.

Other than undoing democracy, genocracy paves the way for genocides and genocidal massacres. It is organically built around making one genos superior and another inferior. The latter resists and are murdered en masse, as we have been seeing in Gaza for a long time. Genocracies normalize genocide as a possible political strategy, especially in this era of the war on terror. The result of this normalization is the banality of genocide, to paraphrase Hannah Arendt.

On the theoretical level, I again stress that the concept of genocracy solves two problems in the official definition of genocide: the problem of intent and the problem of group innocence. Genocratic movements are constitutionally genocidal. For them, the problem is the existence of other genos, whether those genos do something or do nothing at all.

WP: Tell us more about genocracy in the Syrian context, specifically. How did genocracy emerge in Syria? How did it function? What were its effects on state and society?

YHS: Syria in the long Assadist era was an example of minoritarian genocracy, and one that was quite aggressive in undoing the Syrian demos. In Syria and the Middle East, genocracy takes the form of sectarianism. Hafez al-Assad built an engine that sectarianized Syrian society for more than half a century by sectarianizing Syria’s security apparatuses and the military formations with internal security functions. This facilitated identification with the regime for some while alienating others.

Other than this, his regime destroyed opposition parties, both secular and Islamist, as I mentioned. These two mechanisms—sectarianization and politicide—tore Syrian society apart, countering the appearance of a Syrian people. Leftist and secular parties were able to bring together Arabs and Kurds, Muslims and Christians, Sunnis and Alawites, and others. But the regime destroyed these communities at the hands of sectarianized internal intelligence services (mukhabarat), undoing the Syrian people. It was a sort of political engineering of identities that left them open only to destruction.

In the mid-1970s, Kamal Jumblatt, the progressive Lebanese leader, said that Hafez al-Assad sought an alliance of minorities against the Arab Sunni majority. When he was assassinated in 1976, it was most probably due to that daring statement. There is nothing secular about this method, as some in the West tend to believe. It is merely sectarian.

For more than two generations, Syria lacked organizations and movements that could work on non-genocratic grounds. Relative to other movements, it was Islamists who were in the best position to capitalize on this condition.

WP: Your works expand the conceptual vocabulary with which we can identify and decipher other ways that violence functions. For example, you contrast “oppressive violence” and “genocidal violence.” What is this distinction and why does it matter?

YHS: Allow me first to say that, for many years, I have been much unsatisfied with the tools that the Western academy and think tanks deploy to talk about Arab regimes in general, and the Syrian regime in particular. They tend to submerge them in the encompassing category of “authoritarianism” or “despotism” (istibdad), the term that many Arab thinkers used. In my work, I have tried to develop more sophisticated tools of analysis, including a theoretical model of Assad rule. Some of the ideas mentioned above emerged in the course of this work.

I make the distinction between oppressive and genocidal violence in a recent article commenting on the massacres in the coastal areas of the country, where many Alawites—perceived to be supporters of the fallen Assad regime—were murdered.v Families were killed, houses burned, and properties stolen in a frenzied round of unrestrained violence. Many perpetrators were armed civilians. This was not oppressive violence, perpetrated by regular troops with the aim of quashing an insurgency. It was genocidal violence, targeting people whose guilt was, in most cases, who they were and not what they did. I am afraid that genocidal tendencies have been entrenched in Syrian society during the last fourteen years and the more than half a century of minoritarian genocracy.

The unclear boundaries between the new state and wider armed sectors of the Sunni majority, which developed a powerful victimhood narrative in the last few decades, have blurred the line that separates oppressive from genocidal violence. In the article I mentioned, my aim was not only cognitive, but also normative. I want the country to veer away from vengeful, sectarian, genocidal, “violent violence,” and toward a more restrained violence, when necessary. That later should be unviolent, humiliation-free, proportional with the crimes committed, and fully unrelated to the identities of the targeted people.

WP: Another important distinction that you theorize is that between “manual” or “close” rule on the one hand, and “mental” or “remote” role on the other. These concepts extend some of your arguments about torture as a mode of producing political power, which you present in your book, The Atrocious and Its Representation. What do you mean by manual and mental rule, and what do we learn when we juxtapose the two?

YHS: The idea of manual rule is quite simple; it is ruling societies through direct violence that essentially involves inflicting pain on bodies. It is rule through torture. It requires physical closeness between the torturers and the tortured, as well as loss of abstraction in the relationship between state and society.

Manual rule is a structure of power that is quite distinct from Foucault’s biopower, where discipline replaces torture and where power emanates from everywhere. I would add that modern industral violence is also distinctly characterized by remoteness. There is something remote and detached in the exercise of physical violence in biopower.

By contrast, manual rule is characterized by closeness, almost intimacy, in the exercise of power. Manual rule is sovereign-centered, where sovereignty is defined by “make die” or “let live,” and where the life of the sovereign outvalues all the lives of the homo sacer(s). “Assad or no one” epitomizes this condition. While sovereignty is about oneness, politics is about plurality. And, as you can guess, manual rule excludes plurality and politics.

I conceptualize manual rule in opposition to mental rule in the way that sociologists began to discriminate between manual and mental work in the nineteenth century. Mental rule is practiced through rationalized rules and regulations. The rule of law falls into the category of mental rule, as does Foucault’s biopower. We are not talking about freedom as opposed to tyranny. I do not believe these two forms of power are equal, as Foucault himself might have said.

Syria’s transition will be superficial if the country remains gripped by the manual rule paradigm. Under manual rule, politics and even society are impossible. I think departure from this paradigm is, in itself, a revolution and the thing that gives me the highest hope.

WP: Our discussion thus far has focused largely on the genocidal logics of Assad rule. What are the legacies of Assad’s genocidal rule for Syria today? How do years of both genocracy and genocidal violence shape challenges facing the current transition in Syria?

YHS: Other than huge destruction of infrastructure and the economy, other than the fact that close to ninety percent of the population lives under the poverty line of two dollars a day, other than more than half a million murdered and 113,000 forcibly disappeared, the worst legacy of genocidal Assad rule is entrenched sectarian hatred, especially between Sunnis and Alawites, as evidenced during the five bloody days of March.

The new team in power seems to be unable to resolve this problem. They are Islamists themselves, and their discourse and practices were extremely sectarian. They have been showing moderation during the last few years, but their political imaginary cannot perceive Syrian society except as one composed of religious and confessional communities. This is a genocratic imaginary. Their idea of inclusivity is tied to this perception, which excludes political parties or views them as irrelevant.

They do want to stabilize the country and find a political solution to the inherited divisions. But their rule is based on Sunni supremacy—not only because they are the majority or the fact that they were discriminated against during the long Assad “eternity,” but also because of Sunni Islamists’ imperial imaginary. They identify with the history of Islamic empires and their conquests and expansions. They feel it is their right to have the upper hand and rule unilaterally. They can be moderate and pragmatic as long as their primacy is preserved, and turn brutal when it is endangered, as we saw in March.

Another legacy of Assad family rule is the result of long-term politicide: nearly full destruction of political parties. Trade unions and independent social organizations were equally dismantled. Syria has been a political and social desert for decades, and we are starting from scratch to learn how to organize and move ahead.

WP: In this context, it is important to discuss sectarianized violence that has occurred since Assad’s fall, and especially the massacres leading to an estimated 1,500-2,000 deaths in Syria’s coastal regions in March 2025. What do people need to know to understand that violence?

YHS: As I said before, it was genocidal violence, rooted in phobias and victimhood narratives, both of which are characteristic of genocratic politics. One way to understand that violence is to think of it against the background of tectonic changes in Syrian social geology. What happened on 8 December 2024 is seismic, the largest change in Syria’s history since independence in 1946, if not since the emergence of the modern Syrian polity at the end of World War One. Such changes are usually associated with all sorts of danger. Every single Syrian was afraid there would be unspeakable massacres before or during the fall of the regime. It took three months before the unspeakable took place.

In talking about geologic change, I do not mean to deny Syrians’ agency—not only that of the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) upper echelon, but also that of the innumerable Syrians who kept the flame of hope alive. I simply want to represent the fact that the change was enormous, indeed apocalyptic, to the degree that it overwhelms the agency of everyone. This was clear when the brutal violence erupted on the coast. It happened like a natural disaster, without most of the actors wanting it or being fully able to control it. The irrationality of the Syrian political system over two generations facilitated the descent into the abyss.

I do not oppose human rights approaches to those massacres, and I do want to see the perpetrators held accountable for their crimes. Fundamentally, I also want to see Syrian politics move from the realm of nature to that of reason. It will be a great step forward if a national investigatory committee into the events on the coast calls things by their real names and achieves justice for the victims. This would have an important rationalizing effect on the new authorities and on Syrian society at large. Still, it is useful to think of what happened against a backdrop of tectonic change.

WP: What are the most important things that must happen for Syria to have a future liberated from the violence that has caused so much suffering for so many Syrians in the past?

YHS: Criminalization of torture. If it is one thing, it should be this. People’s bodies should be safe and out of the reach of those who rule the country. It is a sort of habeas corpus principle that curbs the powerful from inflicting what they can on the bodies of the weak merely because they can. This may force the latter to develop less savage methods of governance and move toward mental rule as opposed to manual rule.

I think this opens up the idea of constitutionalism, understood as a set of restraints on state power. The main problem in Syria and the Arab world at large is the inhuman, at time monstrous, formation of the state. Rather than being a public, moderate, lawful, and unifying power, the state has been a private, extreme, divisive, and arbitrary power. That is why it has fostered extremism, unlawfulness, and sectarianism among its subjects. People were more positive towards the new states for a generation after independence, before they developed different forms of resistance in parallel with the monstrous turn in our politics in the 1970s and after. Some of the resistance movements, the Islamists in particular, developed absolutist and nihilist tendencies themselves, exacerbating the vulnerability of our societies.

One aspect of unconstitutional power is eternal rule. Eternity cannot be achieved without annihilation, as I’ve said before. This should also be criminalized.

Notes on contributors: Yassin al-Haj Saleh is one of the foremost intellectuals of Syria and the Arab world today. In 1980, he was arrested as a member of the democratic wing of the Communist Party for his opposition to the tyranny of the Assad regime. He was released from prison in 1996. His wife, Samira, was kidnapped in a suburb of Damascus in 2013 and has since disappeared. From 2017 to 2019, al-Haj Saleh was a fellow at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin, and subsequently a EUME Fellow of the Gerda Henkel Foundation at the Forum for Transregional Studies. Among his nine books appearing in multiple languages is The Atrocious and Its Representation: Deliberations on Syria’s Destroyed Form and Its Laborious Formation, which is currently being translated from Arabic to English.

Wendy Pearlman is the Jane Long Professor of Arts and Sciences and Professor of Political Science at Northwestern University, where she specializes in Middle Eastern politics. She is the author of six books, including We Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled: Voices from Syria (New York: HarperCollins, 2017) and The Home I Worked to Make: Voices from the New Syrian Diaspora (New York: Liveright, 2024).

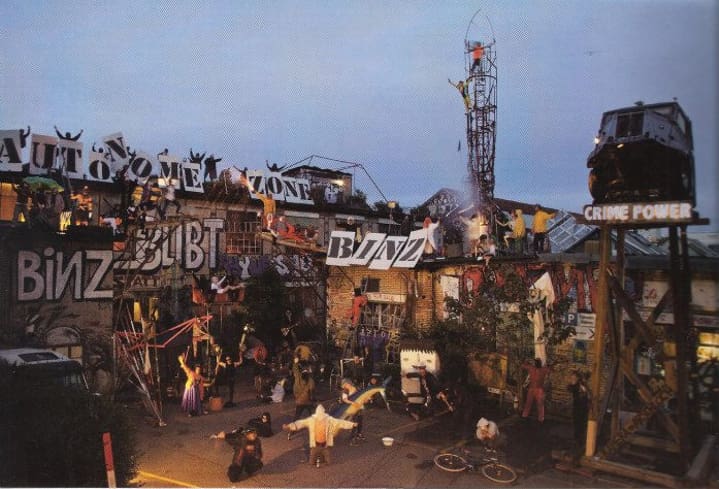

Featured image source: Al-Jumhuriya

Notes

i Barbara Harff and Ted Reobert Gurr, “Toward Empirical Theory of Genocides and Politicides: Identification and Measurement of Cases since 1945,” International Studies Quarterly 32, no. 3 (1988): 359-71.

ii A. Dirk Moses, The Problems of Genocide: Permanent Security and the Language of Transgression (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

iii On the question of context an 7 October, see Donald Bloxham, “The 7 October Atrocities and the Annihilation of Gaza: Causes and Responsibilities,” Journal of Genocide Research (3 April 2025).

iv On the war as organized callousness, see Siniša Malešević and Lea David, “Gaza and the Sociology of War,” Journal of Genocide Research (11 May 2025).

v See Yassin al-Haj Saleh, “Repressive and Genocidal: Reflections on State Violence in Syria,” Al-Jumhuriya, 12 March 2025 (in Arabic). On 6 March 2025, armed men loyal to the former regime of Bashar al-Assad launched attacks on state security forces in the coastal governorates of Latakia and Tartous. Caretaker government authorities, along with armed groups supportive of them, counterattacked. As violence escalated, pro-government militias carried out mass communal and sectarian massacres targeting Alawite civilians. Images circulated of bodies lying in the streets, as did reports of armed gunmen going house-to-house and killing civilians based on their religious identities. According to the United-Kingdom-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, at least 1,700 Alawite civilians were killed by 12 March.