AntiNote: This academic lecture and Q+A by professor Kate Starbird was recorded and livestreamed by the University of Washington on 24 February 2025. The video was made private and replaced with a cleaner version, and we will embed it at the bottom of this post, but the intermittent disruptions to the public address system in the auditorium during the lecture were an odd, startling distraction that make it a less than ideal artifact for circulation.

We thought preserving the lecture in text form could be a small but significant way to assist in making these important words accessible. The subheads dividing the lecture into sections are our own addition.

From the event’s introductory remarks by university provost Tricia Serio:

Kate Starbird is a professor in the the department of human-centered design and engineering in the College of Engineering at the University of Washington. She is also the cofounderand past director of the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public, an interdisciplinary research hub which formed in 2019 around a shared mission of resisting strategic misinformation, promoting an informed society, and strengthening democratic discourse—all incredibly important in this moment.

Kate Starbird’s groundbreaking research has made her the leading academic and public voice on one of the most pressing societal issues: the spread of misinformation and disinformation. Her work, which examines how social media and other digital technologies are used during crisis events, is pertinent to many global concerns including climate, public health, democracy, social justice, and education.

Her timely research also leads to broader questions about the intersection of technology and society, including the vast potential for online social platforms to empower people to work together to solve problems, as well as salient concerns related to abuse and manipulation of and through these platforms, and the consequent erosion of trust in institutions.

Today, professor Starbird will discuss her current focus on how online rumors, misinformation, and disinformation are produced and spread during crises and breaking news events. She’s especially interested in the participatory nature of rumors and online disinformation campaigns, and the roles we and others play on social media and beyond.

Post-lecture Q+A conducted by university vice provost Ed Taylor.

People are misled not just by bad facts, but also by faulty frames.

Kate Starbird: I am thrilled to be here today, to have an opportunity to share my team’s research with all of you. I’m truly honored to have been chosen by the UW faculty to give this lecture, and thankful to my colleagues in my department and the Center for an Informed Public for nominating me.

I brought a lot of content, so I’m going to jump right in. I’m going to start with a tweet that was shared in 2017 during hurricane Harvey. Has anyone seen this image before?

A shark ostensibly swimming in the flood waters of the hurricane. For those of us studying disaster events on social media, we saw this same shark allegedly swimming on the freeway in every major hurricane from hurricane Sandy in 2012 to hurricane Harvey in 2017. The story was entirely false, the image fake. But that didn’t stop social media posts like this one from receiving massive amounts of online attention. In this case, hundreds of thousands of engagements in the form of comments, likes, and retweets.

Fast forward to the LA fires last month, and these same dynamics have, if anything, gotten worse. Can anyone see anything wrong with this image?

There’s an extra D on there. It’s fake! It’s a synthetic image made by generative AI, or artificial intelligence. During the LA fires, online spaces were filled with images like this: AI slop photos and videos meant to grab your attention. But that wasn’t the only source of false claims. We also saw conspiracy theories about the LA fires being a planned event, which is a common trope that’s been repeated during fire events all over the world in the past few years, including the devastating fires in Maui last year. In both events we saw hundreds of political point-scoring rumors designed to exploit the tragedy for political gain and to garner attention in the form of likes and reposts along the way.

These are all behaviors my team has been seeing and studying on social media during wildfires and other crisis events for more than a decade now. This isn’t something that just came up with the internet; rumors have always been a part of how we make sense of crises and novel events—but they are supercharged in our modern moment and within our modern information systems. And the reasons why shed light on many things, including the reconfiguration of political systems around the world.

Let me explain. As I do, I’m going to tell you a story about my team’s research over the past ten, fifteen years or so.

A note on terms

Before I get too deep, I want to get some of the academicky stuff out of the way. I’m going to start with definitions, and I want to warn you that the vocabulary in this field is dynamic, it’s contested, and in some places it’s actively adversarial. What I mean by that is, some of the words I’m going to introduce here have been intentionally redefined in some communities to make them difficult to use, to make it harder to talk about some of the problems we face.

Misinformation is a term we hear a lot. Misinformation is information that’s false but not necessarily intentionally so, whereas disinformation is false or misleading information that’s purposely seeded and/or spread for some kind of objective—political, financial, or reputational gain of some kind.

Disinformation isn’t entirely false, but it’s misleading; it’s often built around a true or plausible core and then layered with exaggerations and distortions to create a false sense of reality. Disinformation doesn’t always function just as a single piece of information but often as a campaign—many different information actions that work together. And though disinformation is inherently intentional at some level, it’s often spread by unwitting agents who are or become true believers of the falsehoods.

A third term I’ll refer to a lot in this talk is conspiracy theory. Conspiracy theories are explanations of an event or situation that suggest it resulted from a secret plot or conspiracy orchestrated by sinister forces.

These three terms have received a lot of attention in recent years, and they are valuable for describing certain things, and I am going to use them. But I’m also going to offer another term, one that has a much longer history in the research, and one that my team relies on in our work.

That is rumor. Rumors are unofficial stories spreading through informal channels that contain uncertain and/or contested information. They are a byproduct of the natural collective sense-making processes that often take place in times of crisis or information ambiguity as people attempt to cope with uncertain information under conditions of anxiety.

Rumors are natural. They also often turn out to be false—but some rumors turn out to be true, or somewhere in between. From this perspective, rumors aren’t inherently bad. They serve informational, emotional, and social purposes. So this is where our research began: with a focus on rumors, and trying in some ways not to really problematize them.

I mentioned the term collective sense-making, and I will come back to this over and over again in the talk, so I want y’all to pay attention here. Recently we’ve made some conceptual progress towards understanding rumors through a data-frame theory of collective sense-making. I’m saying “theory” here, but it’s going to be okay. My colleagues and I have argued that collective sense-making, the process that produces rumors, takes place both through facts and through frames.

By facts I mean all of the data or evidence we have about the world or an event, including through our own experiences and through others’ experiences that are related to us. And by frames: according to [Erving] Goffman, these are mental structures that help us interpret or make sense of those facts or that data. The facts we have on hand often determine which frames we use, and the frames we use often can help us connect those facts and give them meaning.

Frames are both individual and collective. They are both in our heads and also out there in the broader discourse, where they can be shaped through conversations—both organically and strategically. In this talk I will explain how people are misled not just by bad facts, but also by faulty frames.

A note on research methods

Here’s our last piece of academic business. Let me talk a little bit about our team’s research methods. These methods have a lot to do with why I’m standing up here today: I firmly believe it was our research methods, our deep engagement with the data at multiple levels, that made us early experts in online rumors and eventually disinformation.

Our approach builds off the methodological innovation that was being done at the University of Colorado by Leysia Palen, who was my advisor there, and colleagues in the field of crisis informatics. This approach adapts methods of constructivist-grounded theory, and applies those methods to big social data. Our method is a grounded, interpretive, and mixed-method approach: we deeply integrate both qualitative and quantitative techniques, blending computational approaches with manual analysis. We visualize data at a high level to identify patterns and anomalies, and then we dive into the data to see what’s happening in those places. We often move back and forth between these different perspectives: from ten thousand feet, and tweet-by-tweet.

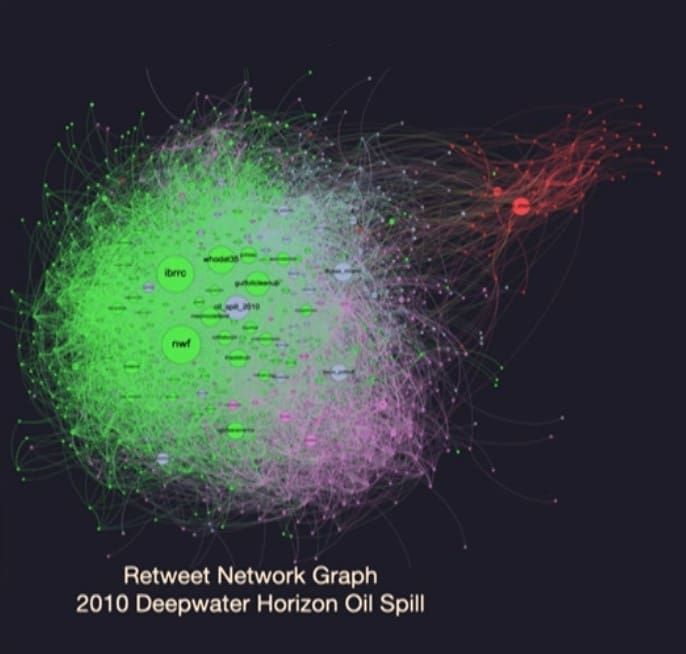

One technique we rely upon a lot is the network graph, like this one:

It’s from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. The nodes here, or the circles, are entities—they are social media accounts or websites—and the edges are connections between those entities (for example, when one account retweets another). These network graphs provide visual artifacts that help guide our qualitative research, which uses them to identify general trends and anomalies—like this strange little red section here, which revealed an early rightwing trolling operation anchored by a deceptive account, back in 2010.

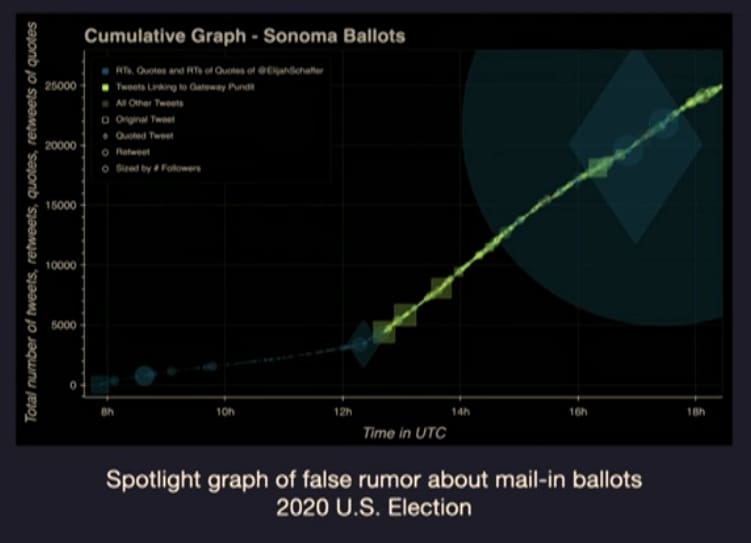

Another technique we use a lot is the “spotlight graph.” This is a technique we developed for visualizing how information flows through Twitter or other similar kinds of sites, and especially the role of influencers—accounts with large audiences—in shaping those flows.

The X-axis here is time, and the Y-axis is the cumulative number of tweets or posts that have been shared by that time. Individual posts or tweets are plotted along this graph and they are sized by the number of followers that the posting account had—in other words they are sized relative to the number of people who would have seen the tweet. This technique, which grew out of earlier efforts, reveals how influencers, or high-follower accounts, can “spotlight” or amplify others’ posts, helping them to go viral.

Here’s what we have found

Now for a glimpse at some of the research findings, which is what we’re all here for. We’re going to put them together in some interesting ways later. Between 2013 and 2016, our team conducted more than a dozen studies of online rumors across different crisis events. I want to give a huge shout-out here to iSchool [Information School at the University of Washington —ed.] professor Emma Spiro, who’s a collaborator in much of that work, and Bob Mason, who was here for the first study, as well as the National Science Foundation which funded this research.

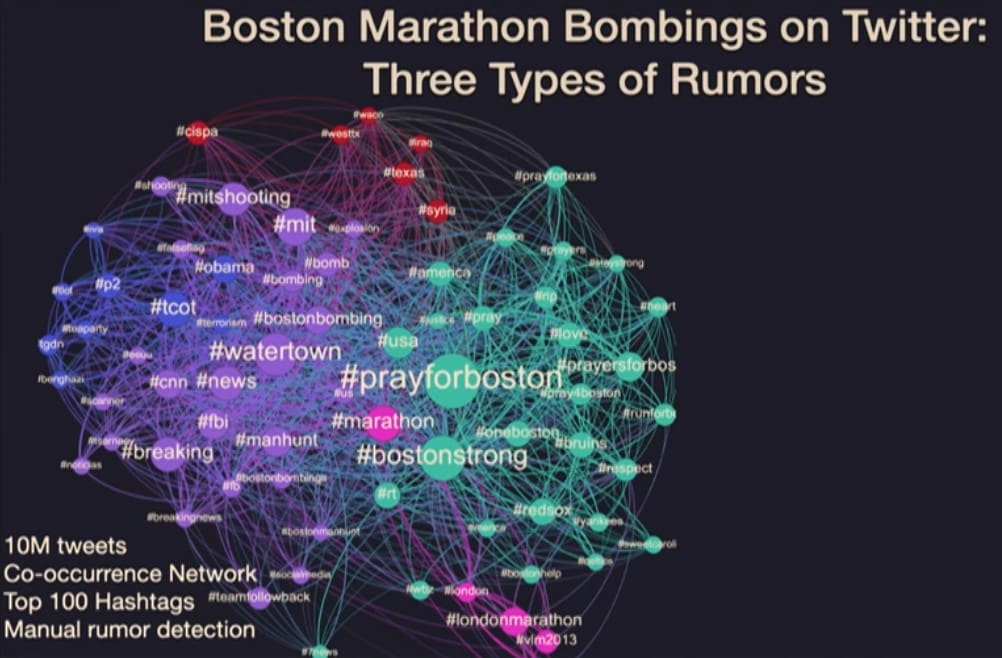

Our first study of online rumoring examined social media use, specifically Twitter, in the aftermath of the Boston Marathon bombings. This was a horrific event that occurred in April 2013. Together with the event of hurricane Sandy a few months prior, the bombings represented a sort of tragic inflection point in the evolution of how people use social media during crisis events, and a point of recognition of how collective sense-making could go awry in online environments.

Using APIs that were publicly available at the time, we collected about ten million tweets related to the bombings; we then employed a combination of network graphing, temporal visualizations, and manual analysis of tweet content to identify several rumors that were spreading in that conversation. We found three salient types of rumors.

One type was what we refer to as a sense-making rumor [in lavender], where mostly well-meaning people were just trying to make sense of the event. After the bombings there was considerable activity around trying to identify the culprits, and in several cases the crowd got it wrong—including pointing the finger at innocent individuals like this young man:

Though most of the online sleuthing activity appears to have been well-meaning, in some cases the sense-making effort seems to have been intentionally manipulated, with people introducing false evidence to support certain theories. After the real culprits were found, there was a moment of collective reflection as people recognized how digital volunteerism could turn into digital vigilantism.

Another type of rumor is what we might call clickbait [in light green]. Clickbait rumors were cases where people purposefuly spread sensational and false claims to gain attention. They often include images: this false claim that a little girl was killed running the marathon was accompanied by an image, likely lifted from a Google search, of a little girl running a completely different race. Bad actors were beginning to recognize they could leverage these events to gain visibility, and that the attention they captured could lead to instant cash through crowdfunding activity, or reputational gains—long-term reputational gains: followers they could exploit later for other reasons.

A final category of rumor we identified in that first study was the conspiracy theory [in blue]. From our perspective, conspiracy theories look like sense-making, but a corrupted form of sense-making where the theory—that the event was orchestrated by secret forces—is pre-determined, and then the audience works to find information that will fit into that theory. In this case the claim was that the real perpetrators were Navy SEALs or some other US-government agents. On the graph, conspiracy theories tended to take place within the more political areas of the conversation.

I want to note that in 2013, conspiracy theories seemed like a small part of the conversation. We almost chose not to feature them in our initial paper, because I didn’t want to be up here standing on a stage talking about conspiracy theories for the rest of my life. But here we are.

After that first study, we completed several more studies of online rumoring during other crisis events and breaking news events. Here are a few things we learned along the way. Initially, we actually went into the space thinking we were going to prove existence of a “self-correcting crowd”—that a crowd would somehow find the falsehoods, they’d be quickly called out, and the truth would rise to the top. That’s just not what we found.

Our team began to understand that we weren’t primarily looking at rumors and accidental misinformation, but pervasive disinformation that was sinking into the fabric of the internet.

What we found was that the crowd was rarely self-correcting; that over and over again rumors spread faster than verified facts. We also saw that professional journalism couldn’t keep up with the pace of the news; they were busy verifying things, and the information was flowing too fast. Sense-making can go awry or be intentionally manipulated: bad actors were exploiting these attention dynamics by spreading rumors, and they were becoming baked into the network as influencers.

Over time, we began to see that rumoring—and conspiracy theorizing in particular—was becoming an increasingly salient part of the online discussion during crisis events. What had seemed marginal was growing more central. Initially I had pushed my students away from focusing on conspiracy theories, and over time we realized that we just couldn’t ignore them.

Around about 2015, our research on online rumors began to lead us, following many users on the social media platforms, down the rabbit hole. We stumbled in from a couple of different directions, but what we found at the bottom was often very similar.

Let me go back to a simple observation that we had about conspiracy theories during the Boston Marathon bombings. Among other quirky characteristics, one thing we noticed about conspiracy theory tweets in our data was that they often cited or linked to a multitude of strange websites (at least they were strange to us at the time). When tweets about other rumors linked to websites, they were usually articles debunking the false claims, but these conspiracy theories linked to sometimes dozens or hundreds of different websites, and a lot of them we’d never heard of. At the time, I wasn’t really familiar with Infowars, but I became familiar with it afterwards.

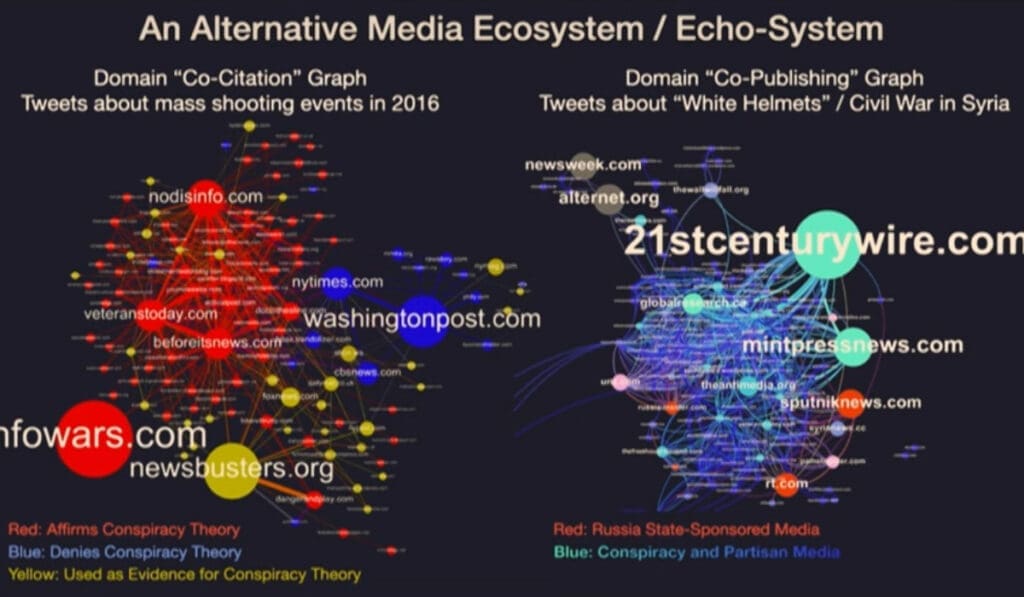

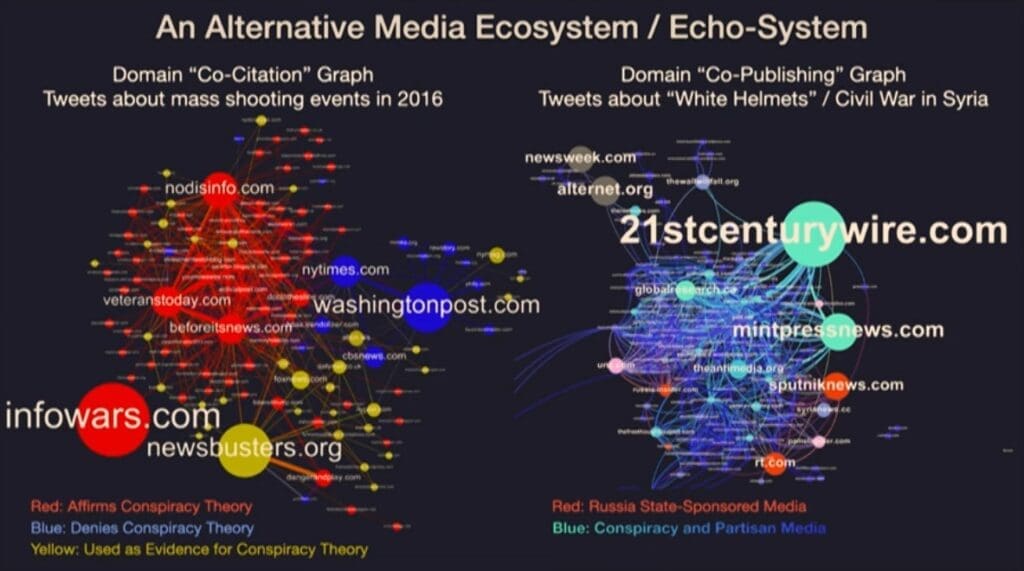

The tweets about these conspiracy theories provided a window into what we might call the alternative media ecosystem. These are two different views from two very different conversations:

On the left are websites cited by people discussing conspiracy theories about shooting events in 2016. This ecosystem consists of different kinds of websites: clickbait sites, websites almost exclusively covering conspiracy theories, state-sponsored propaganda from Iran and Russia, and hyper-partisan media outlets.

My team and I spent a few months doing deep, qualitative content analysis of the websites in this graph, and I do not recommend that. It took months for us to recover. The content was disorienting and depressing. We found that many of the websites didn’t just carry one conspiracy theory, but they featured many conspiracy theories, from claims about UFOs to vaccines to pedophile rings. We began to think about how folks encountering this stuff might start to see the world through a corrupted epistemology, where they repeatedly interpret data about the world through a frame of distrust and conspiracy.

Around this time, our team began to understand that we weren’t primarily looking at rumors and accidental misinformation, but pervasive disinformation that was sinking into the fabric of the internet—into the recommendation algorithms, into the networks of friend/following relationships—in ways that would be increasingly hard to unwind. This alternative media ecosystem was gaining prominence in part through the spread of rumors, conspiracy theories, and disinformation.

And though this ecosystem contained messages targeting both the far right and the far left, its content was resonating with the rise of rightwing populism around the world. State-sponsored information operations, like those from Russia, were actively shaping this alternative media ecosystem, spreading inane conspiracy theories at times, but also reinforcing this corrupt epistemology, and suddenly pushing propaganda and disinformation for geopolitical advantage.

In our early work, we occasionally used the term disinformation, but we really didn’t understand what it meant, initially. That changed after 2016, as we and other researchers, journalists, and the public became aware of the Russian government’s interference in the US political discourse at that time. Our team’s insight into this campaign actually arrived a bit accidentally, via a project that wasn’t initially part of our rumoring research.

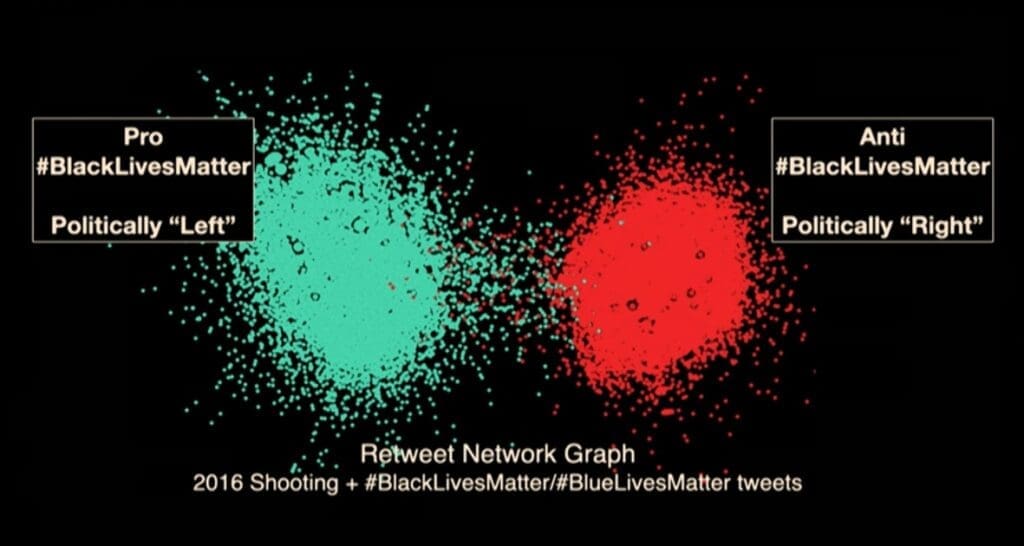

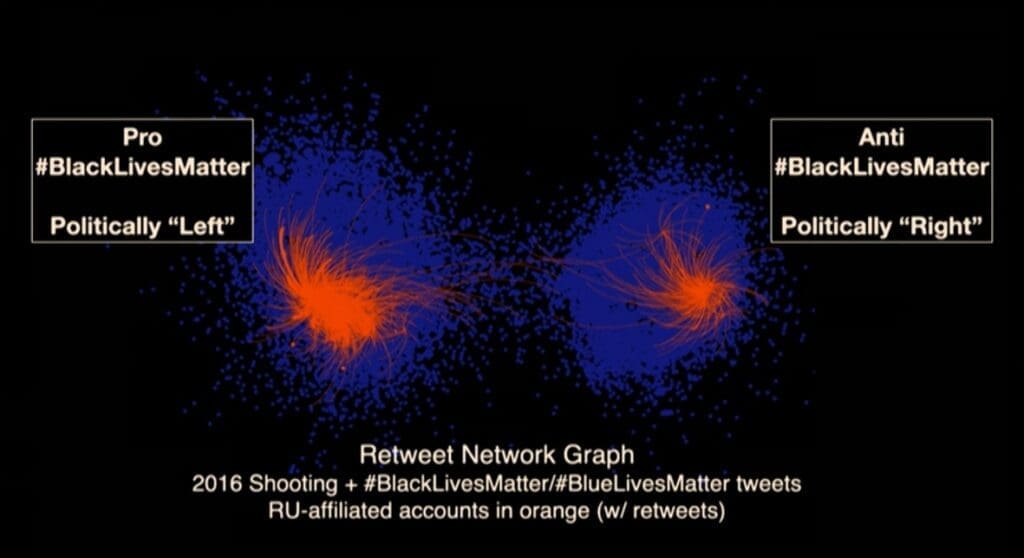

In 2016, a few of my students were studying framing contests within Black Lives Matter discourse. As part of that work, we created a retweet network graph of Twitter users who participated in conversations around shooting events in 2016, including several police shootings of Black Americans, where users employed either the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag or the #BlueLivesMatter hashtag. This graph revealed two separate communities, or echo chambers, on either side of this conversation.

Pro-Black Lives Matter accounts are on the left (and most of these accounts were also politically left-leaning or liberal), and then anti-Black Lives Matter, on the right, were consistently politically right-leaning or conservative. When people talk about online polarization, this is what it looked like structurally in 2016. The two sides created and spread very different frames about police shootings of Black Americans. At times the discourse was emotional, divisive, and honestly uncomfortable for our research team. There were racial epithets on one side and calls for violence against the police on the other.

We published this study in October 2017; a few weeks later, in November, Twitter released a list of accounts they had found were associated with the Internet Research Agency in St. Petersburg, Russia. They’d been running disinformation operations online targeting US populations during the same period of time as our Black Lives Matter research.

I remember going through a list of these IRA accounts. It was nighttime, I came in, I saw a tweet about it, I looked it up—and I realized I recognized some of the accounts that were associated with the Internet Research Agency. We’d featured some of those accounts in our paper. Their names, their handles were in some of our tables of some of the most-retweeted accounts in this conversation. They’d even been the authors of some of the more troubling content that we’d reported on.

Quickly, my collaborators on this project cross-referenced the list of Russian trolls against this graph, to see where these trolls were in the conversation. This might not surprise you now, but this did surprise us then.

Troll accounts are mapped here in orange, and the graph reveals that the Russian disinformation agents were active on both sides of the Black Lives Matter conversation on Twitter in 2016. They weren’t doing the same thing on both sides, but they were there on both sides. A few were among the most influential accounts in the conversation. An orange account on the left was retweeted by @jack, then CEO of Twitter. Several orange accounts on the right had integrated into other grassroots organizing efforts on the conservative side and were repeatedly retweeted by rightwing influencers.

It turns out we’re all vulnerable to rumors and disinformation, especially online, where it’s difficult to know who we’re communicating with as well as how information was created, where it was created, and how it got to us.

The events of 2016 led to an increased awareness of our vulnerabilities online. In the aftermath, there were thousands of media articles, hundreds of research studies, as well as considerable work by social media platforms to attempt to address these vulnerabilities.

“Weaken from within,” from within

When we reflect upon the story of online disinformation in 2016, we think of it predominately as foreign in origin, perpetrated by inauthentic actors or fake accounts, and coordinated by various agencies in Russia. That’s not the whole story—in fact that’s not even half the story—but that’s the one we told ourselves, an easy one that allowed us to focus on outside actors and top-down campaigns.

But fast-forward to 2020: we saw a very different story, particularly when we look at false claims of voter fraud, claims that were at the center of the 6 January 2021 attack on the US capitol. That effort was primarily domestic, largely coming from within the United States. It was authentic, perpetrated in many cases by “blue-check” or verified accounts, and the 2020 disinformation campaign wasn’t entirely coordinated but instead largely cultivated—and even organic in places, with everyday people creating and spreading disinformation about the election.

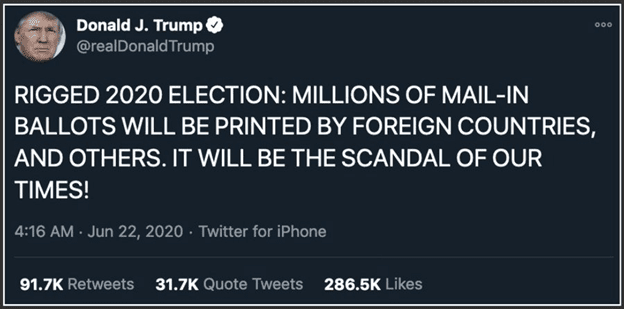

Let me try to explain how that works. First, political elites set a frame, or a false expectation of voter fraud.

For example, in this tweet, posted in June of 2020, then-president Trump claimed that the election would be rigged, that ballots would be printed and ostensibly filled out in foreign countries, and that this would be the “scandal of our times.” This voter fraud refrain was repeated over and over again in the months leading up to the election. It became a prevailing frame through which politically-aligned audiences would interpret the results of the election, and it led to the corrupted sense-making process I mentioned earlier.

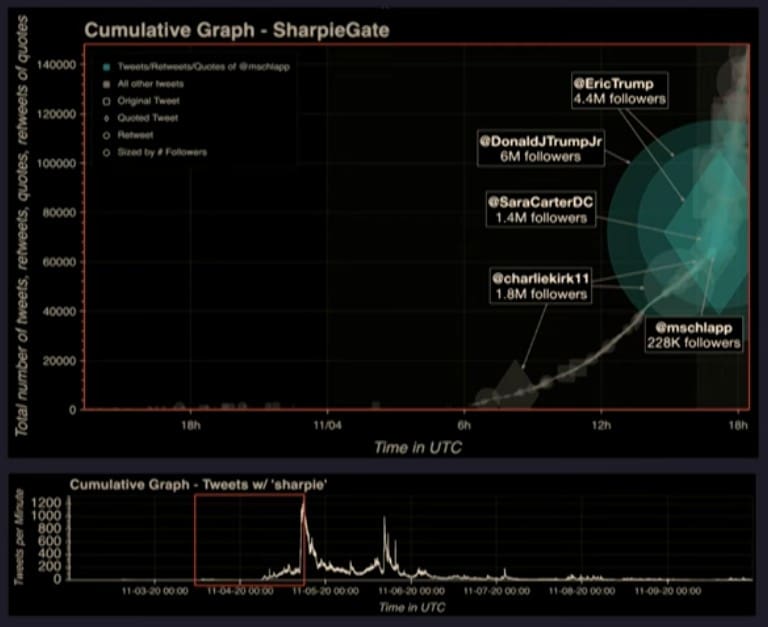

Eventually, Trump-supporting elites, social media influencers, and online audiences would collaborate to produce hundreds of false claims and narratives. A prime example of this was #SharpieGate—the second SharpieGate (there was another SharpieGate, but this is the one about the election. There’s a lot of “Gates” around here). This narrative began with a number of people posting stories from different parts of the country describing how they or someone they knew or heard about had been given Sharpie pens to vote, and how the pens had bled through the ballots, and how they were worried their votes wouldn’t be counted because the pen bled through.

Disinformation isn’t just coordinated manipulation by foreign spies and scammers; it’s not just outsiders manipulating our discourse, and it’s not just top-down. Disinformation, and propaganda more generally, in the modern era, is participatory.

These claims were especially salient in Arizona, which was a swing state that could have made a difference in the final result at the national level. Officials there attempted to correct these concerns on election day, explaining that the ballots were designed to be used with Sharpie pens, and that the bleed-through wouldn’t affect the vote-counting. But these official statements did little to alleviate concerns, which grew as more and more people shared their fears.

Initially, the tone of many Sharpie tweets was one of concern: worries that the votes wouldn’t count, directives to bring your own pen. But as time went on, the content took on a more suspicious tone, as social media users began to interpret the evidence through the frame of voter fraud. Eventually the discourse shifted to the explicit accusation that this was an intentional effort to disenfranchise specifically Trump voters—and the shift occurred as the content began to take off and go viral.

Here we have two views of how the term “Sharpie” spread in election-related Twitter data. The graph at the bottom is a basic temporal graph, and the highlighted section shows the volume of tweets per minute during election day and up to the moment when this false narrative begins to go viral. The top graph is one of our spotlight graphs, showing the cumulative number of tweets on the Y-axis at the same time.

The SharpieGate conspiracy theory began in the accounts of everyday people, people with small accounts, often voters who were misinterpreting their own experiences. You can hardly see them there in that little red box. But it begins to take off with the help of a small set of influencers, social media accounts with millions of followers. In many cases, this occurred through spotlighting, where a small-follower account shared a claim like this one, claiming that this was Democratic voter fraud and somehow these ballots were not going to count, and a large influencer would amplify this claim, sometimes with a “just asking questions” style so they didn’t have to take responsibility for the claim if it was false. As the SharpieGate rumor spread, it echoed across influencers with even larger audiences. These included political activists, media personalities, and president Trump’s two adult sons.

Many of the false claims we tracked followed this similar pattern: origins in small accounts with few followers and amplification from influencers with increasingly large audiences. In this case, the influencer accounts had picked up on the SharpieGate rumor and were actively pushing it with this voter fraud framing right as the rumor began to spread widely—and right after Arizona had been called by Fox News for Joe Biden. They were seizing upon these Sharpies as a potential reason for that, and claiming fraud.

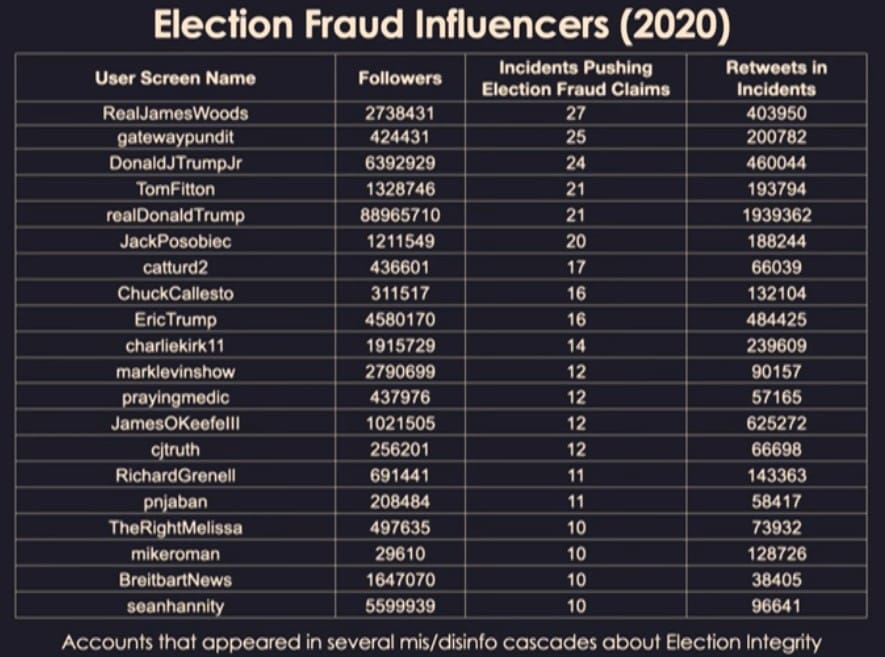

If we look more broadly across the course of the Election 2020 conversation, we find a finite number of repeat offenders who were repeatedly influential in spreading content related to the Big Lie. We created this list of Twitter accounts that were highly retweeted and spreading ten or more different claims of voter fraud—and again, they include president Trump and his adult sons, as well as a cadre of rightwing media pundits, political operatives, and influencers.

Participatory disinformation: a deadly serious theater of the absurd

Perhaps the biggest contribution of this study, and all of our work on disinformation, is this: disinformation isn’t just coordinated manipulation by foreign spies and scammers; it’s not just outsiders manipulating our discourse, and it’s not just top-down. Disinformation, and propaganda more generally, in the modern era, is participatory. Elites in media and politics collaborate with social media influencers and everyday people to produce and spread content for political goals.

Participatory disinformation takes shape as improvised collaborations between witting agents and unwitting (though willing) crowds of sincere believers. These collaborations follow increasingly well-worn patterns and use increasingly sophisticated tools, and they’ve become structurally embedded in the socio-technical infrastructure of the internet.

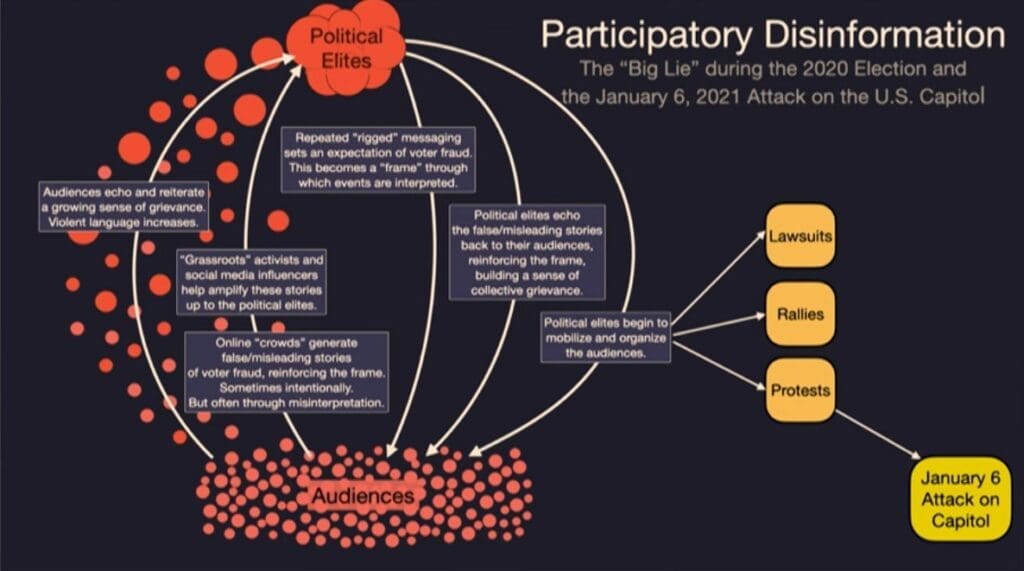

Let me show you a graphic that shows how these collaborations between political elites and audiences work, starting with the Big Lie example.

Political elites repeatedly spread the message of a rigged election, which set an expectation of voter fraud, and this became a frame through which the events of the election were interpreted. Online crowds generated false an misleading stories of voter fraud, reinforcing that frame. Sometimes these stories were produced intentionally, with knowledge that they were false—but often they were generated sincerely through misinterpretation.

Political activists and social media influencers would help to amplify those stories, passing the content up to political elites. And political elites echoed the false and misleading stories back to their audiences, reinforcing that frame, building a sense of collective grievance.

The audiences echoed and reiterated that growing sense of grievance—we saw violent language and calls to action begin to increase. Political elites began to mobilize and organize the audiences into a series of lawsuits, rallies, and protests—and eventually one of these leads to the violent attack on the US capitol on January 6.

Participatory disinformation makes for a powerful dynamic. It’s enabled by social media, but it also implicates the broader media ecosystem, from conspiracy websites to cable news outlets, as well as some members of the political establishment. These types of feedback loops between elites and their audiences seem to make the system more responsive, but also may be leading it to spin out of control. We could see similar dynamics supporting rightwing populist movements all around the world.

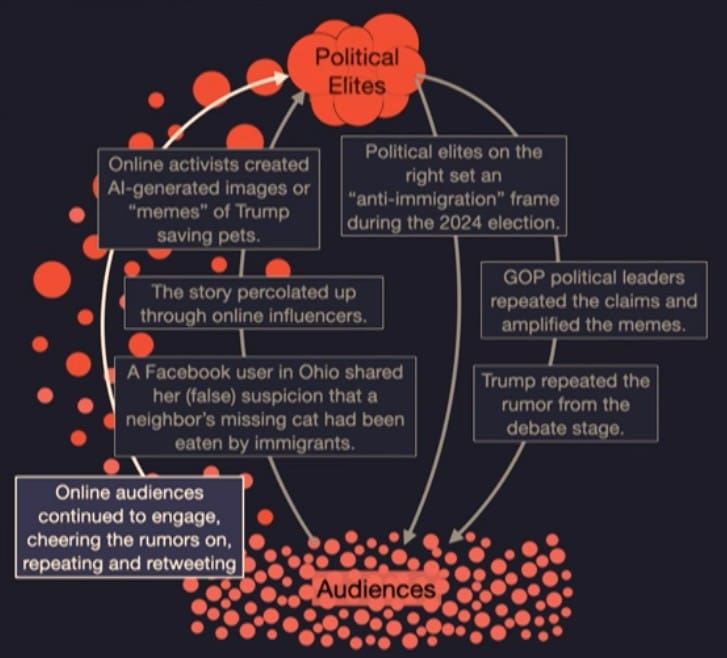

Let me show you another example. On September 10, 2024, Donald Trump stood on the debate stage with Kamala Harris and made the preposterous claim that immigrants in Ohio were eating pets. Many people in the audience were perhaps surprised or shocked by the claim—but the story of how this claim ended up on the debate stage looks a lot like the SharpieGate example.

Political elites on the right set an anti-immigration frame in the 2024 election; the frame became a steady drumbeat over the course of the election, from repeated claims of non-citizen voting to misleading narratives about immigrant-driven crime waves. Likely primed by this frame, late in the summer of 2024, a Facebook user in Ohio shared her false suspicion that her neighbor’s missing cat had been eaten by immigrants. This urban-legend type of rumor was false, likely a misinterpretation of a chicken being cooked at a barbecue. But that didn’t stop it from spreading.

It began to gain traction, first on Facebook and then on Twitter, and it was reposted—or spotlighted—by influencers with larger and larger audiences. Leveraging the anti-immigration frame to support their favored presidential candidate, online activists began to use generative AI tools to create images for memes of Trump saving pets. It’s funny, and it’s supposed to be funny, and we laugh, but it worked for them, which is one of the sad things.

GOP leaders and other political operatives repeated the rumors and amplified the memes. Elon Musk even gave them his blessing through his account on the platform that he owns and has come to dominate. Donald Trump repeated the false claim from the debate stage—but the story didn’t end there. This only brought the rumor new attention, new audiences, and those audiences continued to engage, cheering the rumor on, repeating and retweeting, and often laughing at what soon became a joke—and a jingle, with Trump’s debate comments set to music.

I can still hear that jingle.

What to make of this? Another false rumor that develops and propagates as part of a participatory disinformation campaign, spreading messages that demonize immigrants. I said this before: we’re all vulnerable to rumors and disinformation—but the phenomenon is also politically asymmetric. Our work and others’ has shown that Republicans and Trump supporters spread far more false claims about the 2020 election, which shouldn’t be surprising considering the events of January 6. Other research shows that this phenomenon extends to other topics, not just elections, in other countries, and is tied specifically to rightwing populism, not traditional conservatism.

Why? My colleagues and I have a theory, and it’s about how rightwing media works and how rightwing political movements circumvented traditional media and tapped into the attention dynamics of online media environments and online rumors.

While Democrats have continued to rely upon traditional media, committed to factual and balanced coverage which broadcasts their messages from one to many, Republicans have leveraged the dynamics of the new and digital media to build a powerful, explicitly partisan, and participatory alternative media ecosystem which offers agency to its audiences, who can play a role in the deep storytelling of who the party is and what they believe.

There have been some malignancies that have been visible to folks using these systems for a long time. Some of the same features that helped protesters organize things in the Arab Spring have been used by white supremacists to gain visibility and power.

We see the rightwing media and politics as a kind of improvisational performance that’s taking advantage of the affordances of new and digital media. On stage are a theater of influencers performing roles based on a lightweight set of rules or conventions. They follow a loose script, improvising and collaborating towards a shared goal. They don’t exactly know where they’re going with each scene, but they know what the themes or the frames of the day are, whether it’s “voter fraud” or “social media censorship” or “They’re eating the pets!”

The theater metaphor helps account for the interaction between influencers: they feature each other on each other’s shows; they celebrate and amplify each other; there’s conflict, some of the characters have foils. But at the end of the day, they’re all on the same team.

This metaphor also provides insight into the interactions between the influencers and the audiences: as they perform, the influencers do call-outs and call-backs with a shared audience who’s truly part of the show. The audience cheers, jeers, and steers the actors as the show unfolds.

The actor-influencers are intensely tuned in, watching the likes, the reposts, the comments, ready to give the audience more of what they want. And the audience has the power to guide the performance. From this perspective, influence doesn’t just flow from the influencers up on the stage out to the audiences, but from the audiences back to the influencers. Feedback is instant, and they can be extremely reactive and adaptive to the audiences. They build their stories collaboratively. Audience members have agency; they’re truly part of the show.

At times, a spotlight extends out onto an audience member who shares their story about Sharpie pens, or their suspicion that their immigrant neighbor is eating the pets, and the audiences create the content to fill the frames of the day. The influencers amplify that content, and political leaders increasingly are acting upon it.

This is the essence of participatory production: improvisation according to a loose set of rules and norms about how the game is played. The motivation for participation is high; the audience is literally part of the performance. They’re not just shaping politics with their vote, they can interact directly with their leaders and shape political rhetoric and outcomes with their voice. They feel empowered as never before, and there are even opportunities for audience members and new content creators to come up onto the stage and become influencers themselves as the spotlights converge onto them.

The rightwing media ecosystem is explicitly partisan and intensely participatory. It emerges from and is reinforced by the attention dynamics of social media. It facilitates collaborative storytelling through engaging rumors and memes. Its gatekeepers have not been erased—they’ve been replaced by influencers, and these influencers play an outsized role in mediating news and political discourse. They are judged for authenticity rather than veracity, and they can be captured and radicalized by their audiences.

Rage against the bullshit machine!

When I first heard that I’d been selected to give this lecture, almost a year ago, I had a very different talk in mind. And when I finally began to craft this talk in December [2024], as many of us were collectively making sense of the election results, I was focused mainly on describing why Donald Trump and the Republicans had done so well within online discourse and within the election results themselves.

A lot has happened since then. Facebook rescinded its fact-checking program and harassment rules. President Trump pardoned the perpetrators of January 6, even those who perpetrated violence. There are efforts underway to change the history of those events, so the heroes are villains and the villains become heroes. The billionaire owner of the platform that we once studied, Twitter—now X—has been captured by his conspiracy theorist audience and is now taking apart government agencies one by one.

Conspiracy theories are animating the self-destruction of the US government, from science agencies to humanitarian response organizations, to the departments of education and labor. Conspiracy theorists who have risen to prominence on the dynamics I’ve described here—in fact, who are nodes on some of those graphs—are now at the helm of our intelligence agencies as well as our health and human services. And most recently, Trump has made foreign policy statements echoing Russian propaganda about Ukraine. The stakes are clearly higher than ever before.

I started today’s talk with a focus on rumors, but what I’ve been describing is no longer just accidental rumors and sense-making gone awry. What I’ve described is a machinery of bullshit that has become intertwined with digital media, has been effectively leveraged by rightwing populist movements, and is now sinking into the political infrastructure of this country and others.

So I’m going to end with this message borrowed from some of my colleagues at the Center for an Informed Public—they know who they are. We need people, all of us, to fight back against the disintegration of reality. We need teachers to keep teaching and researchers to keep doing research. We need everyday people to keep improving their digital literacy to better understand how our sense-making processes get hijacked by strategic manipulators and the attention dynamics of online systems.

We need people to keep speaking out against the attacks on democracy, on human and civil rights, on decency, and on empathy. And we, all of us, need to start building the social and informational infrastructure to counter this bullshit machinery.

This infrastructure needs real journalists to keep investigating and reporting, but we can’t just rely on the logic of traditional media. We can’t wait for the New York Times or Washington Post to tell the story or to build the graph or create the meme that helps people understand what’s happening around us. We need to leverage the participatory dynamics of the digital age—but complement that with a commitment to truth and of building, not destroying, a just and sustainable future and a strong democracy.

While our team, and perhaps many of you, were afraid to talk about conspiracy theories, the loudest and most vile voices have run the table. We can’t afford to be quiet anymore; we can’t afford to be polite anymore. We need to make our voices heard; we need to become the opinion leaders and influencers in our families, on our social feeds, in our classrooms, our churches, and our sports teams. We need to rage against the bullshit machine.

* * *

Ed Taylor: You began by studying crisis informatics—the pro-social things that people after disasters did, how people came together, how we shared information, neighbors helping neighbors, which is a fundamentally good thing. And you’ve described the pandemic as the “perfect storm for misinformation.” Describe how that came to be, and how the pandemic in that moment, in 2020, impacted you and your colleagues.

KS: We know that during times of uncertainty, rumors are just part of how we make sense of things. The pandemic had an extended period of uncertainty—it’s natural for people to be trying to make sense of that and to be getting it wrong. On top of that, we had online dynamics that were already supercharged. Rumors were already supercharged; conspiracy theory communities were already gaining a foothold in those spaces in 2020. The confluence of this event, which was massively disruptive and had an extended period of uncertainty, and the dynamics of our information systems—I wrote something in March of 2020 about how this was going to be an informational disaster, just because of where those dynamics were.

And indeed by May, we could watch and see these networks of accounts—this is one graph I skipped today—of “wellness” New Age anti-vaccine networks beginning to link up with pro-Trump folks who were angry with how some of the response was happening, and with conspiracy theorists in the QAnon community. We could start to see these things come together during this extended period of uncertainty, and as COVID-19 begins to go into Election 2020, these networks that were spreading COVID rumors and conspiracy theories begin to be facilitating the spread of election rumors as well—and some of the influencers in that anti-vaccine COVID-19 misinformation [campaign] were on the [capitol] mall on January 6, and some of them were inside the capitol building, and you can see the intersection of those networks online and then in real life.

ET: Let’s talk about algorithms for a moment. In some ways I find comfort in being able to go to social media and see that I’m surrounded by people who are like-minded; in some ways it’s become a community for me. But it can become a kind of echo chamber.

Are algorithms part of the solution? Part of the problem? Where’s the nexus here?

KS: The algorithms and the networks are part of why these spaces are so toxic. It’s not just the algorithms themselves; it’s how they fit into the attention economy, how certain information rises to the top. It turns out to be stuff that’s engaging, that’s novel, that makes us feel emotionally triggered: laughter, outrage, those kinds of things. Those things rise to the top, and that’s not necessarily accurate things—that’s not necessarily reality.

We all know we’d rather watch a show about a good conspiracy theory than a movie about the factual things about what happened at some point. These are things that are compelling, they’re entertaining. And the algorithms have emerged to give us what is entertaining to us. Those algorithms were gamed in some ways; they would reify things: if you started to look at one conspiracy theory, you might get recommended more. If you started to look at a person sharing a certain kind of political view, you’re going to get recommended more people who have that political view.

The algorithms profoundly shape what we see in online environment, so we have this idea that everyone’s voice is equal. But that’s not exactly true. The folks who were able to game those algorithms gained an outsized voice on these platforms, so that fits into those influencers that I talked about.

ET: In 2020 when we had to go online as a campus, we thought it would be a good thing to provide the very best teachers and scholars that we have to our students on all three campuses, and did an asynchronous course. You were the first person I asked to do a lecture and provide content for that moment in time in 2020, and you said yes.

One of the things I was struck by with you was that you have the ability to talk about fairly complex research to a range of people, from community members, high school students, and the general public—everywhere I looked you were on television, you were on social media, you were somewhere. And yet there’s a great degree of criticism of this work.

Why are the critics so harsh in response to you? And how has that impacted you and your colleagues?

KS: This could be a two-hour conversation, maybe a two-year one. But quite succinctly, there are people—and people with a lot of power at this point—who have gained their power by exploiting these systems. There are people who have benefited from this machinery of bullshit I commented on (and it’s a technical term—it’s speech that’s meant to be persuasive without regard for veracity; it’s not true or false, it just doesn’t care) and from the way these systems work, from exploiting them. They’ve gained these outsized voices and they don’t want people to understand how they’ve done it.

They don’t want solutions to address it, they don’t want content moderation, they don’t want the platforms to be redesigned. When researchers go to try to expose that, when we create a table and say, Here are the influencers who repeatedly spread lies about the 2020 election, that puts us on their radar of folks they don’t want talking about this. Quite interestingly, they use the accusation of censorship to try to silence researchers like myself. And some of them have been effectively silenced.

That’s why the criticism comes, and it’s been really hard on our team. It’s been hard on students and the staff at the Center for an Informed Public. I personally lost almost a year of productivity trying to figure out how to respond to some of the criticism. But it also has made us stronger, and we’ve realized: You know what? What are you going to do now? Once you’ve been criticized and you’ve built up some scar tissue, it’s actually helped me and some of my colleagues be more firm in what we’re able to say now, and not willing to be cowed by this bad-faith, strategic criticism.

ET: How do we fight against this bullshit machine that you speak of? What tools do we have?

KS: It’s a throwing-spaghetti-against-the-wall kind of moment. We do need journalists to keep telling stories and reporting, but the way that professional journalism works, from one to many, is not well-adapted to this moment. And the right has done a great job of exploiting participatory dynamics. We have to find ways to help people tell their stories about what’s happening in this moment, to amplify them, and to get those out in the world.

We have a set of social media platforms—some of them are so toxic I won’t use them anymore, but there are some where our friends and family are there, and if we want to reach them we have to go to those platforms. But we have to find platforms where we think we can speak our truth and get that truth out to people.

What I’ve been telling my friends and family is that each of us needs to be an influencer or opinion leader in our own groups. We were so scared to talk about these things, and we got a little bit uncomfortable, and we need to go back out and have conversations, and tell the stories of what’s happening right now, and find ways to get those out into the world.

ET: Why hasn’t the left been able to exploit this kind of misinformation and disinformation on social media in the ways that the right has?

KS: Well, if you have a commitment to truth, it’s hard to spread disinformation. That’s part of it. Also, the left in this last election really tried to rely on traditional media to tell their stories—everyone’s mad at the New York Times and the Washington Post, but traditional media does not have the same commitments as the partisan rightwing media does towards how they tell stories, how they create their content. So we’re comparing things that are completely asymmetrical.

The legacy media is not going to do for the left what the far-right alternative media ecosystem is doing for the right. The left needs to find something different if they want to fight back.

ET: Here’s a question from a student: As university students centering our careers, what are some key skills or research areas we should focus on to pursue a career in understanding misinformation? How can we best contribute to this field in terms of research and practical applications?

KS: There’s no one answer to this. This field is so profoundly interdisciplinary (and it has to be). We need historians and we need data scientists; we need storytellers, we need journalists, we need computer scientists who understand AI; we need legal scholars who understand how things fit into the law. The most important thing is to be balanced, to capture a couple of those things.

The students who do best on our research team have interdisciplinary backgrounds, double majors like history and computer science. Jim Maddock, an undergraduate who was a lead student on our Boston research, was a history and HCDE [human-centered design and engineering —ed.] major. Kaitlyn Zhou was HCDE and [computer science]. Interdisciplinarity is what I would encourage, and to not leave the humanities behind. If anything, we need them more than we ever have.

I’m an engineer, but we just can’t leave the humanities behind. It’s so important.

ET: I’ve been following your career and research, and there have been moments when you’ll say something that comes off as subtle, but you wondered out loud whether or not you could continue your work, you and your team, at a public university, because the response had been so harsh and so critical and painstaking for you. It made me realize that this work you’re doing is tremendously courageous, but it comes at some cost.

How do we protect researchers who are doing this kind of work, and who are committed to the truth? At a deeply personal level, I’m glad you stayed here. You mentioned it matter-of-factly after a meeting, and I thought—and as I walked in the door and noticed the number of officers here that aren’t normally here, I found myself thinking about the gravity of your work and the courage it takes to do it.

How do we protect scholars like you?

KS: I am hugely grateful for how the University of Washington responded to the things we were experiencing. I don’t mean the university operates all at once—it’s people who are in this room. A lot of it was the leadership in my department, leadership at the iSchool, folks who stood up for us within the university and helped explain these attacks were bad-faith, and there’s a reason for it, and this is really important scholarship that we need to have space for.

To be honest, that is what gave me the courage to keep going. There was a time—it’s rough now, but we had a preview of what was coming to the rest of the world. Some of the people you’re hearing about that are characters in this world have been characters in our life for the last couple of years. We have known them, they have made public records requests of us, forty-plus public records requests of the Center for an Informed Public or me directly. Some of the things the University of Washington has done helped reduce the burden of those requests. That’s been hugely important for our team.

Helping with legal support when we’ve needed it has been really important. I had to do a hostile interview with a congressional committee, and it was really nice to have really great legal support sitting next to me. Knowing that the University of Washington was there to step up and support us—I told someone I was going to see a counselor, and I saw her a couple of times, and the third time I said, I don’t know if I need to see you anymore, and she asked what changed. I said, I realized the University of Washington is behind me.

ET: I’m going to go back to the pro-social things you started your research with. Do you hope that social media information systems can go back to the heart of the work that you started with? Pro-social, neighbors helping neighbors, communities keeping each other safe? How do we get back to that fundamental purpose?

KS: Those features are still there, those capacities are still there. I’m looking out at some of the colleagues who have studied and critiqued these systems for a long time, longer than I have, and I think a few folks may say there have been some malignancies that have been visible to folks using these systems for a long time. Some of the same features that helped protesters organize things in the Arab Spring have been used by white supremacists to gain visibility and power.

I do think there’s opportunity for redesign; there’s opportunity for us to vote with our feet and go to platforms where we feel safer, where the discourse is more reality-based. But I don’t know that we’re not always going to be dealing with an information system, from here on out, that is not the one we grew up in and that does have some real challenges. We’re just uniquely vulnerable as humans in these systems because of the ways these systems have evolved—especially when it’s an attention-based economy.

I mentioned that a little bit and don’t have time to unpack it, but the way these systems work is they capture our attention. They’re there to keep us locked in, and that dynamic means that some of these malignancies are there to be exploited, both accidentally and intentionally.

ET: In this moment in time, in light of the work you do, in light of what you see going forward, what gives you and your team a sense of hope?

KS: I don’t know if I can speak for my team, but my sense of hope has, in the last five years, been anchored on interacting with young people and the junior scholars who are doing this work, and how committed they are, not just in this space but across a lot of the adjacent spaces of young people who are really working on hard problems where the stakes are very high and where they may not always feel like they’re winning—and they’re still out there working on those things and trying to make a difference.

To see their courage and to know that we’re passing on that baton—these are the folks who are going to keep going. Things don’t feel great right now. There are a lot of things that are pretty frightening if you’re at a university and share a certain set of values. A lot of the things we’d hoped five or six years ago, to defend democracy—If we just do this we can stop things from happening and things are going to go back! Things are profoundly changed, and we’re going to have to start thinking on a much longer timeline of clawing back some of the rights and freedoms that people are losing.

For me, my hope is with these junior scholars who understand that the timeline is long and they’re dedicated to keep working at it.

ET: You told me once in a class that you had let go of your athletic identity because you wanted to put yourself fully into your scholarly identity. But are there any lessons that you take from your career in athletics that can apply to your work in a public university at this moment in time?

KS: You’re not quite capturing exactly why I wanted to leave behind my athletic identity; there’s not enough time here for that, but part of it was a lot of sadness of having left a career and having to cope with that, but also wanting to see if I could do something else. For years, as a PhD student, I don’t think my adviser had any idea that I had been a very good athlete—it just didn’t come up. I was really able to be a completely different person.

For a while, I couldn’t necessarily see the connections between that first career and this career. But I’ll tell you, in the last two years and definitely in the last six months, I’ve been using a lot of sports metaphors. You can’t win if you only play defense. A lot of sports metaphors coming out! I will say, when things got really frightening a couple years ago, when we were feeling a lot of the attacks, and I saw my colleagues ducking and covering—not here at the University of Washington, but other places, and totally understandable, because it was pretty frightening—I feel like having that first career and a lot of positive feelings, especially in Washington state, in Seattle, where a lot of people knew me and had good feelings about me, I was able to take some risks around standing up and fighting back.

Maybe a little bit of courage from being an athlete or something else; I do feel like I began to lean a little bit more on my first career when things started to get heated with this research.

ET: Any questions you wished we’d have asked?

KS: What happened with the audio?

ET: I want to conclude this way: I’ve been watching Kate for years; I knew Kate before she knew me. But all the more profound in 2020—I kept looking for colleagues who would stand up and lead, not just our university, but our community and nation, during a time of real difficulty and crisis. Prior to the election, I kept looking for people to stand up during a time of real difficulty and crisis, and Kate was one of those people I kept seeing over and over again—pre-tenure, post-tenure—with a level of courage I don’t think I’d ever seen at the university before.

So if you wouldn’t mind joining me in doing a second standing ovation for Kate Starbird…

KS: Thank you.

Printed with permission. All images are stills of Kate Starbird’s presentation slides in this video (posted subsequently and separately from the livestream link, which is now private):