AntiNote: Here we present a polished transcript of an insightful conversation with Shareah Taleghani about her then recently published book, Readings in Syrian Prison Literature: The Poetics of Human Rights. We were deeply saddened to hear news of Taleghani’s passing in September 2023, after which we felt both immense grief and gratitude for the legacy she has left us with. We regret that she was not around to witness the widespread liberation of prisoners across Syria in late 2024.

In Taleghani’s honor, we encourage readers to carry on with the work she started here, giving voice to the oft silenced and forgotten lives of society’s most marginalized, in Syria and beyond.

Transcribed from the 12 November 2021 episode of The Fire These Times podcast and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole episode:

The international human rights system isn’t working as it was meant to work. Human rights activists in the region are the ones putting themselves on the line to document what’s going on, and they know that the system sometimes fails. My question is: if we look elsewhere, if we look at other forms of cultural production, is it possible to conceive of an alternative system that is more grassroots-bound?

Shareah Taleghani: My name is Shareah Taleghani. I’m an assistant professor and the director of the Middle East studies program at Queens College. My research area is modern Arabic literature and Middle Eastern cultural studies. In my research I focus a lot on dissent, cultural production, and human rights, and how those three things intersect.

Elia J. Ayoub: Thanks a lot for doing this. We’ll be talking about your recent book, Readings in Syrian Prison Literature: The Poetics of Human Rights. Can you give us some background on the book?

ST: I became interested in prison literature when I took a class at NYU as a graduate student with Elias Khoury. We read different works of Arabic prison literature, and before that I hadn’t really thought about prison writing or prison literature as a category. A group of us came together to translate a collection of poetry by Faraj Bayrakdar—we started this project in the early 2000s, and we had trouble finding a publisher for it at the time, so it’s just coming out now.

I was going to write my dissertation on an entirely different topic, but I became more and more interested in researching writings about prison. It was also a period in the US, in the post-9/11 era, where there was increasing concern about the US’s systemic human rights violations in the so-called “War on Terror.” There was the emergence of a body of scholarship that’s loosely labeled “literature and human rights” or “the humanities and human rights.”

That body of scholarship didn’t exist prior to 9/11. Scholars in the humanities began to really examine the relationship of the academy to human rights, all while the US’s systematic human rights violations became more public. It’s not that there weren’t human rights violations perpetrated by the US government prior to that; it was just more publicly discussed and debated, especially the when it came to the use of torture.

So I ended up in Syria. I got the chance to meet with different writers and ask them questions about their writing and why they wrote. I decided to focus on bringing the study of writing about prison, into conversation with this body of scholarship about literature and human rights. I was really influenced by Joseph Slaughter’s work, whose book I highly recommend, called Human Rights, Inc. But the works of literature by Syrian authors that I read were really the most inspirational.

What I tell students I work with now (and the question I was asking myself then) is: What are we learning from this work of literature? What does this text teach us about humanity? What does it teach us about human rights? That’s how I came to read the texts the way I did, and that built the topics of the book I wrote.

The book is based on my dissertation, but there’s a lot more in there— I had the time to read more works of literature, more theory, and more critiques of human rights. That’s basically how it came into being.

EA: The title of your book already says a lot—The Poetics of Human Rights. Can you explain what that means? And did Syrian prison literature give you a new understanding of human rights?

ST: That’s a really good question. I had trouble coming up with a title, as we all do—I use the term poetics because it indicates a systematic study of a body of literature, and poetics also relates to the effects that texts produce. Part of what I was asking myself when I was reading these texts is, What effect do they have on the reader? What do they show the reader?—and not just in terms of content, but in structure and form. How do they affect the reader in a way that is different from human rights reportage?

A lot of what I do is putting these texts in conversation with conventional human rights reportage, to see how they work differently. What do these texts generate that is different from conventional human rights reportage? But also what gaps or fissures do they point to? What erasures exist in the text? What are the silences of the text?

That’s all part of poetics. Human rights are constructed through narratives; human rights claims are constructed through the stories that are produced by people who have had their rights violated. But human rights organizations and the conventions of international law require that these stories be told in a particular way, whereas we have this body of literature produced by Syrian authors that is in some cases poetic, fictional, dramatic. Some of it is non-fictional, but it’s creative and it’s artistic.

I wanted to understand how particular works move readers differently.

EA: Who are some of the authors you get into? I’ve read Mustafa Khalifa’s The Shell, and Yassin al-Haj Saleh’s work. Introduce that body of work, that literature—who are they and what are their books?

ST: The first work of Syrian prison literature I read was Faraj Bayrakdar’s poetry. Previously I had read more Iraqi and Egyptian prison literature. Faraj Bayrakdar has a memoir called The Betrayals of Language and Silence, which is a really important work. The other first texts I read were short stories. I was interested in the fact that, in that particular generation, there were so many authors who chose to write short stories, like Ghassan al-Jaba’i, Ibrahim Samu’il, and Jamil Hatmal.

One of the questions I asked was, Why choose the short story instead of a memoir, or a novel, or poetry? Of course, there were also novels, written by authors like Hasiba Abdelrahman, Rosa Yassin Hassan, Mustafa Khalifa, and Malek Daghestani. So I read all of those, and the memoirs as well.

One of the things I say in the intro to my book is that it’s impossible to write about all of these texts; there are so many important texts that people need to keep reading and writing about. There are memoirs: Ali Abu Dahan, a Lebanese citizen detained in Syria; Heba al-Dabbagh; and others. I’m just naming a few texts—the list goes on and on, and there’s so much more that could be written about.

What I do is focus on a limited set of texts, because if you wrote about everything it would be a three-thousand-page work. But there’s still so much more that could be written about, and now there are all the texts that have been published post-2011, and that includes works like [those by] Bara Sarraj, who was detained in the eighties and nineties but published post-2011. There are works now being published for those detained in the eighties, nineties, and 2000s, and then there’s the next generation: those detained during the revolution and war. It’s a huge body of literature.

It needs to be studied intensively and comprehensively. I just touched on a range of texts, and the way I came to those texts is somewhat arbitrary. I did research in Beirut and Damascus, I tried to find everything published during a certain time period, but it’s easy to miss texts. There is much more to be done. There are a lot of other scholars and PhD students working on the topic now, which is good.

EA: You wrote a piece in 2015 on Tadmor military prison, called Breaking the Silence of Tadmor Military Prison. As a side question, did the documentary Tadmor by Lokman Slim help you in that documentation, or did that come later?

ST: The film came after; I wrote that piece earlier. It focused on texts written prior to 2011. Tadmor allegedly was closed by the regime—although I’ve heard contradictory reports about that—and then it was reopened after the uprising. ISIS allegedly destroyed the prison, but I’ve also heard from Monika Borgmann that it wasn’t destroyed. I still don’t know what’s accurate.

EA: For those who don’t know, Monika Borgmann and Lokman Slim are the founders of UMAM, which is one of the most active groups in Lebanon that do memory work. Unfortunately, as many people know by now, Lokman Slim was assassinated earlier this year. The family accuses Hezbollah; I’m fairly convinced it’s Hezbollah too, but others would say “allegedly.”

ST: I’m fairly convinced it was Hezbollah also.

EA: My position on this is pretty clear; I’ve written a piece on it for L’Orient Le Jour.

Anyway, all of these people who you read—they are writing in a context that has its specificities, but also some universalities. I suppose this is the value in talking about Syrian prison literature as a genre. Can you give us some idea of the setting they are writing in? Can you give us a sense of the country and the prisons they are writing in and what they are reflecting on?

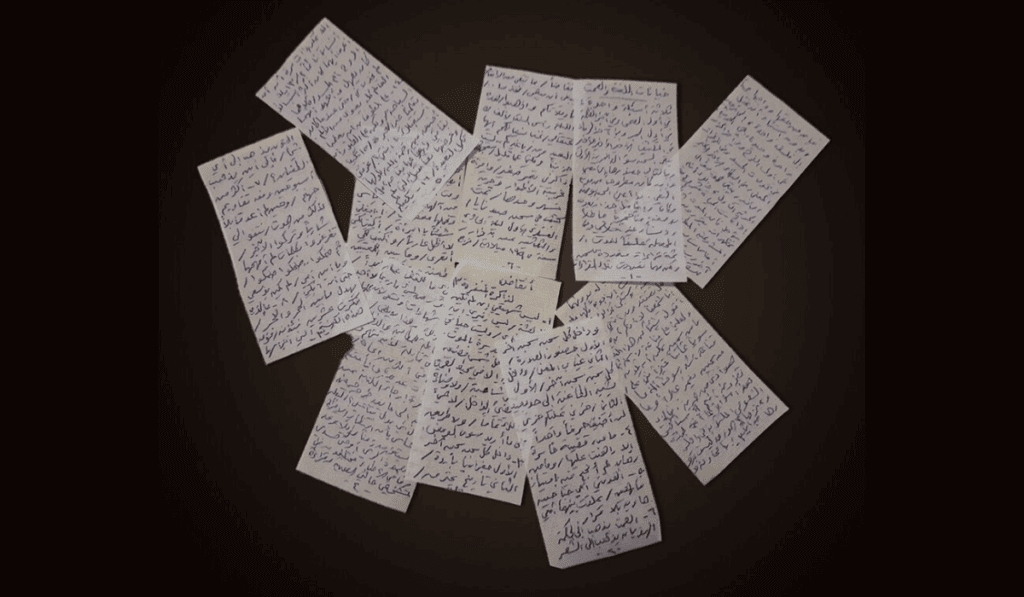

ST: Many of the texts I write about were written in prison, sometimes under atrocious, harsh circumstances—for example, in Tadmor—where detainees didn’t have access to writing utensils and had to create writing utensils and forms of paper, or used oral composition and then memorized the texts that were later written down.

So in some cases the texts were produced in very harsh conditions. In the collection of poetry that we translated by Faraj Bayrakdar, he talks about this in the interview that’s included with the collection, fashioning writing utensils from whatever products are available. The typical thing is to write on cigarette paper. In some cases, when these texts were finally recorded, they were smuggled out of prison, but in other cases, depending on the regime of the prison, when it was less harsh, writers were able to write while incarcerated with typical notebooks and pens or pencils. And in some cases they were written after release.

So it varies from text to text, how each text was produced. That’s one of the things I learned in the process of talking to people and studying these texts, and asking where they came from or how they came to exist. Each text has a story, and the story of how each text was produced and circulated in its final form is also important. This detail is often left out, but each text, along with the author, has taken a journey, and we need to remember what that journey is, because of the very harsh circumstances in which some of them were produced.

EA: You spend a bit of time in the introduction talking about how censorship works in Syria. That was interesting, because a lot of people, when they think of censorship in a context like Syria, think it’s constant and that it’s been the same model for the past five decades. In fact, you mention how there is a very specific regime tactic centering the role of arbitrariness and unpredictability, and there’s even a term associated with this: tanfis.

Can you talk about how censorship works in these contexts? And what is tanfis?

ST: I write about it by drawing on the work of other scholars. People who are especially interested in this should read Lisa Wedeen’s book Ambiguities of Domination, Rebecca Joubin’s book[s] on Syrian television drama, and also miriam cooke has written about it.

The system of censorship is arbitrary. Arbitrariness is a characteristic of authoritarian regimes—or at least this is what I learned by talking to authors: certain works of art are not automatically censored. For example, the ministry of culture would allow something to be published but prevent its distribution, or occasionally allow something to be published and circulated because it was considered “acceptable,” and it varies from text to text.

I was in Damascus in 2004 or 2005, in Abu Rummaneh, and there was a book fair by the ministry of culture—I was really surprised to see a collection of poetry by Faraj Bayrakdar being sold at a book fair sponsored by the ministry of culture! It was a collection of poetry that he had composed in prison.

The arbitrariness is one factor—people can never tell what will be allowed and what will be prohibited—but the other part of it is the fact that people circumvent the system. They were circumventing the system prior to people being able to put everything in a PDF and put it online. And now with digital publishing, the regime just can’t control it. People circumvent the mechanisms of censorship everywhere—it’s true in Syria, it’s true in Iran, it’s true in Egypt. Although the regime tries this tactic of allowing a few things to be published—this is part of tanfis, to “let off some steam,” or to have some form of licensed or commissioned criticism—people still circumvent that.

The regime cannot control what people produce and circulate. They can control what’s sold at a ministry of culture book fair, but even just from living and working and studying and traveling in the Middle East, it’s amazing how many banned books you can find in bookstores. They’re still there.

EA: I’ve never had that much difficulty finding Israeli books in Beirut bookshops—novels or history books. Ilan Pappé’s books are translated into Arabic, and those are technically illegal in Lebanon, but they’re there.

There is definitely some parallel to Lebanon, although it’s worse in Syria. Lebanon likes to portray itself as relatively more open-minded and liberal, but I know in cinema, which is what I study, it seems like the censors are sometimes censoring because they’re having an off day, and sometimes they let things pass because they’re fine with it. Usually the censorship has to do with sex, religion, or politics.

I remember watching World War Z in Lebanon, and while thirty minutes of it was removed, the rest remained and you could still guess what the topic was. There are other cases with Lebanese directors where the movie can be censored, or first allowed and then censored, allowed to be screened once or twice, or heavily edited. There’s a movie called The Kite, where half of it was removed, and it ended up never being screened because of that censorship.

When it comes to arbitrariness, I will mention a personal example: when Lokman was assassinated, I had publicly decided that I’m not going back to Lebanon, and the reason is that I have received death threats from Hezbollah in the past. The arbitrariness of it is that I don’t know whether I am still threatened right now or not. I don’t know, if I go back, whether they don’t actually care and they forgot about me, or whether suddenly they want to remind me that they do remember me.

It’s this never knowing whether there’s going to be a concrete consequence for your action that can actually function as a very effective tool—maybe an even more effective tool, because if the government is always cracking down, people start developing patterns of resistance to it. We start understanding what can be done and what can’t be done. Take the protests in Syria in 2011—I know this from friends and activists: in the early days, they knew where they could and could not go. They knew how to organize themselves.

I used to think that censorship had to be very regular in order to be effective. But actually if you make it irregular it can be even more effective. I suppose that’s what you find in the book as well.

ST: The arbitrariness and the not-knowing is really destabilizing, whether it’s censorship or death threats—which we know Hezbollah does commonly. It’s the not-knowing that can produce forms of self-censorship, even if they’re subconscious. That’s one of the effects—or it can be, unless people are very aware and conscious of it. Which is difficult to do!

EA: Definitely. Syria has always been more difficult than Lebanon, and it is difficult in Lebanon, so I can only imagine how it is in Syria.

What we’re calling prison literature has been going on for decades now. You mention that the first usage of the term “adab al-sujūn,” or “prison literature,” came three years before the founding of the first human rights organization in Syria. Do you think that reveals something?

ST: Arab critics connected literature and human rights well before US scholars did. There was a consciousness of the relationship between detention for explicitly political reasons and violations of human rights, decades ago. There’s a foundational study of prison literature by Nazih Abu Nidal called “Adab al-Sujūn,” where he starts off with a discussion of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. So this connection between writings about prison and human rights was made decades and decades earlier by Arab scholars.

From the studies I’ve read on the history of human rights, in the 1970s globally there was a greater awareness of the language of human rights. This was the time when Amnesty International came into more international public awareness. It took a couple of decades, because the UDHR was established in 1948—as problematic as the concept of universal human rights is, but that’s a whole other discussion.

So we have a Syrian scholar, writer, and critic writing about adab al-sujūn in 1973 (and I have to say that’s the earliest I found in my research; people with greater access to archives might find something earlier) and then this attempt to establish a human rights committee by the Syrian Lawyers Union—which of course was disbanded by the regime. And it wasn’t just that first foundational study of prison literature; there were critics writing in the nineties connecting human rights and works of literature that deal with detention; there was an awareness there.

It’s interesting to read a literary critical study from the 1990s that starts off with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; that’s how one particular scholar and critic opens the book. Those connections were made, and they were made by Arab critics well before this field emerged in the US.

The US context is specifically in the post-9/11 context. For decades, human rights violations, in US consciousness, were perpetrated elsewhere by other people. And we know this isn’t true! We can just look at why the US needed a civil rights movement, right? It’s a country founded on the violation of the rights of Indigenous peoples and Africans who were forced into slavery. But I’m talking about public consciousness of the US committing human rights violations; it really comes to the forefront post-9/11.

EA: On the question of universal human rights, you write, “The truth effects generated by works of prison literature coincide with, confirm, and challenge the truth claims produced by the documentary and generic conventions of human rights.”

Explain that to us, please. Would it be fair to say that Syrian prison literature as you’ve studied it contributes to this challenging of the universality aspect of human rights? And what does that mean?

ST: First, all narratives produce effects of truth, whether they’re fictional or nonfictional. We read something and we perceive the truth of it, whether it’s a philosophical or a factual truth (that’s not me, I’m getting that from reading a lot of genre theory). But when I was thinking about pairing human rights reportage, for example, with memoirs, many of the memoirs document the conditions of prison; they document summary executions; they document torture—in a way that’s parallel to human rights reportage. In some cases these memoirs serve as testimonials and forms of witnessing when human rights activists couldn’t get access to them otherwise.

When I say they “challenge” the generic conventions of human rights, there are a couple ways they do this. You’ll find in particular works that there is a lot of questioning and (forgive the term) interrogation of the possibility of representing the experience. How do you represent the experience of detention to really communicate what it is? How do you write about torture to explain what it is? There’s a lot of questioning and interrogation of the process of writing and the process of representing the experience itself, within the literary works, where authors are directly, explicitly saying, this can’t be completely represented.

This can get into the field of trauma studies. But also, the human being as an entity is constructed in a particular way in human rights discourse and reportage. There are some works of prison literature that depict the human in alternative ways—and in some cases depict the human by representing something un-human. I’m thinking of Ghassan al-Jaba’i’s short stories, for example.

Some works of literature show us that the transparency, legibility, and readability of human rights reportage can be called into question. It can point to gaps in the representations of human rights violations in human rights discourse. It can function as alternative forms of testimonials, and it constructs the human differently.

Part of this is coming from critiques of legal discourse. Human rights are built through a system of international law and through specific forms of language. In my class, we just read the complaint and demand for jury trial of Maher Arar, who was a survivor of extraordinary rendition to Jordan and Syria. There’s a particular way his story is told, and then we looked at alternative forms and the way he tells his own story.

Part of it is thinking through what gets erased in the process of legal human rights claims, and part of it is a concern that, at times, the way human rights claims are made allows authorities or entities who are supposed to respond and do something about it, to ignore it. That, for me, has been a question, as someone who sits in the US, very comfortably in New York, and witnesses time and time again the international human rights system not intervene—in part because of the US government sitting on the Security Council.

So there’s that, and the concept of universality is also at issue. There were people from across the globe involved in the development of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It’s an aspirational declaration.It’s never fully come into existence. It’s never fully been implemented. It’s what is hoped for. But despite the fact that there were international voices, global voices, involved in the creation, it relies on the modern European legal system primarily, and it’s formulated out of that.

I don’t know that I fully answer this in the book, but it’s something for further exploration: by reading these artistic, creative works of literature, and the ways they tell stories, the ways they show humanity and inhumanity, the ways they show human beings—can they help us conceive of an alternative system of human rights? That’s very aspirational, and it sounds naive in some cases. But we know that the international human rights system isn’t working as it was meant to work. It’s human rights activists in the region who are the ones putting themselves on the line to document what’s going on, and they know that the system sometimes fails.

But my question is: if we look elsewhere, if we look at other forms of cultural production, is it possible to conceive of an alternative system that is more grassroots-bound? That question isn’t yet answered, but it’s important to think about. There’s been recent English-language scholarship that critiques human rights—and they’re very valid critiques: that it’s the end-times of human rights, that the rights system should be disbanded—but that doesn’t help people who are actively working through the system right now. There’s no alternative, so can we conceive of an alternative that’s more effective? Maybe on that isn’t tied to the Security Council?

It’s not just the issue of universality. The fundamental flaw in the system is that authority and power is controlled by a few states. We know the story there: those states intervene—or fail to intervene—in their own national interests and to the detriment of different groups of people all around the globe.

EA: You mention the story of Maher Arar. I know him; he was deported first to Jordan and then to Syria right after 9/11, in 2002. He remained in Syria, he was imprisoned by the regime on behalf of the CIA, he was tortured for about a year and stayed in prison for about a year. He’s a Canadian citizen, which is relevant to the story. After his ordeal, he was released from Syria. The Syrian regime itself said he is not a member of Al-Qaeda. He returned to Canada. Canada officially apologized for its participation, but to this day he still cannot travel to the US, and as of 2010 the supreme court of the United States refused to review his case—let alone the fact that the United States never officially apologized.

One thing that I’ve noticed, on this question of universality and looking for alternatives to universality that are actually universal: on this podcast, with some of the guests I’ve had, there are certain experiences and traumas that allow some people to feel empathy towards other people in similar or similar-enough situations. At the end of 2016, when the battle and siege of Aleppo and the fall of eastern Aleppo was happening, there was a protest—maybe more than one—in Sarajevo with over a thousand people. And the people who were being interviewed included relatives of those murdered in the genocide in the nineties, and they were saying things like they know what it’s like to be abandoned by the “international community.”

This sense of abandonment created a sense of shared experience between Bosnia and Syria; I have seen it also in recent years with the treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. I have seen friends, Syrians and Bosnians I know, talking about similarities. It’s not usually necessary for exact details to be replicated, but rather the sense of being abandoned is shared.

I’m wondering what you think, reading Syrian prison literature: is it something that some of the writers reflect on, this universality? Did some of them know that they were writing an experience that isn’t just relevant to them, but relevant to people elsewhere who are imprisoned?

ST: That’s a good question for the authors, unless they explicitly state it. It depends on the work, but my sense from my own readings is that there’s an awareness that incarceration is a global phenomenon. I’m speaking to you from the capital of incarceration, because the US imprisons the highest percentage of its population in the world. I’m about ten miles from Rikers Island, which is New York’s most notorious prison. There’s an awareness of the fact that incarceration happens elsewhere, that political detention happens elsewhere.

You would have to ask the individual authors who they think their audience is. For me, especially as someone who teaches: there’s not a lot of Syrian prison literature available in translation, but I’ve had students who have been incarcerated, and even if it wasn’t for explicitly political reasons, they really identify with what is being expressed in these works of literature.

Imprisonment is a global form of punishment; there’s that. But there’s also the fact that many of the writers I spoke to said they had read works written by other authors—not just Arab authors, but Russian and Latin American literature, American prison literature. There’s a huge amount of American prison literature. They had read and experienced other works of literature.

There’s this connection between the texts, in that some of the experiences are shared. As a reader, I can see the connections. Whether or not the authors intended their works for a Syrian audience, an Arab audience, a Middle Eastern audience, a Western audience, a global audience—it depends on how the author feels. But that doesn’t mean that those works don’t get read elsewhere. They still circulate, and they can still have impact on broad and diverse audiences.

I teach what’s available in translation, and I see the impact that the texts have on students, whether they’ve been incarcerated or not. The question of audience is a tough one, because any text can be read by a reader who it wasn’t intended for; the author can’t control that once it starts circulating.

EA: You write of prison literature becoming one of the foundations for the revolution. I certainly know a few friends in Daraya and Damascus, who participated as activists in 2011, who knew of The Shell, the book by Mustafa Khalifa. I believe Yassin al-Haj Saleh was mentioned a number of times as well. Definitely some people who participated also had this literature in mind.

How would you explain the link between Syrian prison literature and the 2011 revolution?

ST: Part of why I wrote that was in response to the US mainstream media coverage of the Arab uprisings. There was a tendency to ignore the fact that there had been oppositional political movements in Tunisia, Egypt, Syria, and elsewhere; to erase the decades of activism and political opposition, opposition parties, and just talk about the now—and especially focus on the youth and social media.

That was obviously a part of the 2010-2011 uprisings. But it’s part of the larger US public’s ignorance about the history of the region as a whole—these oppositional movements, whether they’re Islamist or Marxist or other leftists, they have existed for decades. That’s part of why I write about that. But my sense is that these works of literature, and the essays and other writings that formerly imprisoned authors have produced, are part of the consciousness. Is it always direct? No. But it’s part of the foundational back story.

Rita Sakr has a book called Anticipating the Arab Uprisings, where she talks about works of prison literature. She focuses on three works post-2005 in Syria; she calls it part of the “political geography” of the Arab uprisings. I hope other scholars will look at this more closely. At least in English, there isn’t that much scholarship about the Syrian opposition. There’s been some about cultural production, but not about the Syrian [political] opposition. But I hope they’ll start examining the history of opposition more, to understand that as part of the back story of the uprisings.

I’m talking about English-language scholarship, not Arabic scholarship, obviously, because that’s different. My colleague Alexa Firat and I worked on an edited volume about dissent, and part of that was in response to this, that the mainstream media coverage of the uprisings in 2011, and even some of the progressive media coverage, was problematic in that it ignored this whole history, this very complicated, long history of political opposition, or just didn’t make any connections to it.

EA: You dedicate the book to the detainees and those forcibly disappeared in Syria, in Iran, and in the US. I find putting those three countries together quite interesting, because it brings up important points which have pretty deep and even radical potential.

The way discourse around these three countries often goes, if we’re talking about Americans, let’s say, it depends a lot on one’s own political preferences at the local level. If it is mainstream discourse, as you mentioned, it could be that they’re generally in favor of the protests in 2011, but at the surface level—they’re usually not digging too deep, not going into the context or the background.

As we remember in 2011—and I saw a repeat of this in 2019 Lebanon, the uprising being called the “WhatsApp Revolution,”—in 2011 it was Facebook and Twitter, back when people thought Facebook was a force for good. I also know of a certain tendency in the US left, to downplay prisoners in Iran or Syria.

So I am very interested in seeing the potential of reading this book, a book that’s on Syrian prison literature and dedicated to detainees, prisoners, and those forcibly disappeared in the US, Iran, and Syria, because I can easily imagine (and I have read) Iranian state media, PressTV for example, saying it’s horrible what happens in American prisons, but saying nothing on what happens in Syrian and Iranian prisons. I would probably see the same on Syrian state media.

In America we see certain norms being reinforced by people who are comfortable, for example, talking about the abuses in Syria and Iran but not in the US, or who are very concerned about prison abolitionism in the US (as one should be) but when the question comes up of what happens elsewhere, it can get a bit messy.

So again on this whole concept of universality: if we are prison abolitionists, we should be abolitionists about that in Syria and Iran and the US. I’m curious about your thoughts on this.

ST: I have very strong feelings about this, and have posted on Facebook my very strong feelings when it comes up. The dedication to detainees in Syria, Iran, and the US is partly from my personal history; it’s also my awareness of the problematic politics of being an Iranian-American writing about Syria at a time when the Iranian regime is one of the key components in buttressing the Assad regime. The book is about Syria, but I’m also very critical of the Iranian regime.

There’s a very problematic pocket in what’s generally referred to as “the left” in the US—and the left in the US is not very left; elsewhere it would be centrist. There’s a very problematic pocket on the left, among progressives and liberals, that tacitly and complicitly, or even directly, supports both the Assad regime and the Iranian regime. In some cases they valorize the regimes, arguing that they’re anti-imperial. There have been some journalists and commentators who have done this, and it’s really problematic.

My stance, that I’ve tried to communicate over and over again (and I have many colleagues who share this stance), is that it is important that we remain critical of the US government—which I am. But it’s equally important not to complicitly support authoritarian regimes that are oppressing people who are sometimes very courageously attempting to struggle for their political freedoms. It’s important instead to stand in solidarity with them.

Part of the problem is this pocket on the left that supports the Assad regime and is sometimes pro-Putin, and often supports the Iranian regime as well—there’s a strain of Orientalism in it that comes out in their writing, that they don’t even see themselves, and they need to be called out on it. I became aware of this because I was involved in the protests against the invasion of Iraq. I got involved in a local peace group. I was living in Staten Island at the time, which is a really conservative area of New York—it’s the only area that voted for Bush, but there was a peace activist group. And people would make really problematic comments, like that people in the region were just “accustomed to dictatorships,” that it’s “cultural.”

I’m like, No. That’s what I mean by the strain of Orientalism, or neo-Orientalism, that feeds through some of these commentaries. We’ve seen it with Syria; we saw it when Qassem Soleimani was killed—I remember I posted on Facebook because I was really pissed off, because I was getting commentary in my feed that was valorizing him. I thought, No. You can critique the US government for effectively assassinating him extra-judicially, just taking him out. But you can also critique his role in Syria committing atrocities against Syrians and other citizens. It’s not one or the other.

People should have consistent stances. If you support struggles for freedom, you should support it across the board, regardless of who the actors are. I’ve seen it in commentary on social media since 2011, but it was happening in 2003 before the US invasion of Iraq. Like when celebrities or liberal politicians go to visit the regimes to show solidarity—you can be against problematic US intervention, but also against the same regimes. It is possible.

EA: I’ve had a number of guests on, and there’s almost like a timeline of when they started becoming aware of these pockets, as you call them. 2003 is definitely an extremely common one, around that time and after that. If it’s not then, it’s after 2011. But it’s been revealing—in recent years I’ve gotten more connected with some Bosnian circles, and some of them have said that they saw this even in the nineties, which I didn’t know anything about.

I’ve definitely dealt with those tendencies for a long time, and it’s still definitely a trigger, but I try and do something constructive with that trigger—which I didn’t used to do before. Before it was just ranting online, and blocking.

ST: I’m not an activist; I’m a teacher and a scholar and a translator. But I do participate in protests, and I have students who are very activist. I’ve also heard this from my students. I have a lot of students who are originally from the region. Either they’re Arab- or Iranian-American, or they’ve come as international students. And the most important thing is to confront it when you encounter it. Because oftentimes what I’ve found is that people’s intentions are good; they don’t understand why it’s problematic. They think they’re doing or saying the right thing, but when they slip into Orientalist and racist discourse, that has to be called out. You have to call it out.

Also, being in Syria in 2003, 2004, 2005 also shifted my perspective. I used to be completely against any form of US intervention, but I think there are times when international intervention has to happen—but it has to be a consensus, and an international one. When the US goes on its own, it usually makes things worse.

EA: Do you have any final reflections?

ST: I just hope that people continue to study and read works of Syrian prison literature. I know people are continuing to study and read, and I hope that more works get translated so they can reach an American audience. If more people in the US read such works, they would have a better understanding.

EA: What are three books you would recommend to listeners, and why those three books?

ST: I’m going to recommend things that are translated. I would recommend Mustafa Khalifa’s The Shell. As the first novel about Tadmor military prison, it’s a very important work. The story is told and structured in a unique way, as an oral composition, and it’s a very graphic but powerful novel. I’m reading it with my class next week, actually.

The other book I would recommend is Faraj Bayrakdar’s A Dove in Free Flight, which is a collection of poetry that he wrote in prison that is coming out just now, and there’s a very lengthy interview with him that was conducted in 2005 that talks about his experience with detention and with poetry.

As for the third book—when I originally started my research, I started reading about American prison literature and then I stopped. I was really focused on works and criticism produced in the Arab world, and then in the past few years I’ve come back to it. A really important work, not just for the American context but to think about prison writing globally, is Dylan Rodríguez’s Forced Passages. I found it to be really impactful for thinking about the differences in context between American prison writing and how it gets marketed and packaged for a particular liberal audience, and Arabic adab al-sujūn and how that generic category was generated in a different context. It’s made me think more about the connections between those who were incarcerated, whether for explicitly political reasons or not, in the US to those incarcerated elsewhere, and also think about the possibility of a global abolitionist movement. Even though it seems very far from happening, what would that look like? I learned a lot by reading it, so I highly recommend it.

EA: Amazing. Thanks a lot for those, and thanks a lot for your time, this has been really informative.

ST: Thank you for having me.

Featured image source: Cover image for Taleghani’s book, designed by Fred Wellner, printed with permission (© Syracuse University Press).