There are elements of neoliberalism that we consider fascistic. Let’s start calling them by their name.

by Antidote’s Ed Sutton

In recent years, there has been a discussion emerging about the rise of neofascism worldwide, with the example of Europe (where it has taken classic, readily identifiable, highly visible forms) being most frequently noted. References to a “21st Century Weimar” were being made, even in mainstream Western media, at least as early as 2012 as Golden Dawn’s political prominence was surging and the economic suffering in Greece appeared to explain it.

The unprecedented success of radical rightwing parties in last year’s EU parliamentary elections and the more recent wave of fascistic anti-Islam movements in Europe (most spectacularly in Germany but with parallels in France, Britain, and elsewhere), not to mention the lethal islamophobic violence that accompanied this wave, have accelerated this discussion.

Though this appears to be just the beginning of a long, hard fight, it is important, as always, to take account of small victories. Thanks at least in part to the scrutiny and resistance that these neofascist movements face (long-standing and quickly-mobilizing antifascist movements have been widely, though often grudgingly, credited for their role), some of them have petered out or simply imploded.

After having attracted multiple tens of thousands of people, repeatedly, to rallies all over Germany, PEGIDA is now a leaderless laughing stock. Their sister organization in Switzerland, after some threatening murmurs early this year, never materialized.

Before that, the then-conservative Greek government cracked down on Golden Dawn and imprisoned some of its more powerfully vile personalities. And now with SYRIZA in power there is some cautious hope that issues like fascists in the police force and draconian prosecutorial and prison policies directed at both immigrants and leftists will be more aggressively addressed.

However, attacks on Muslims and “foreigners” continue across the continent, and the prevalence of xenophobic rhetoric in mainstream discourse has, if anything, increased. Discrimination against immigrants and abuse of refugees is still the written policy of the European Community and its individual member countries, and new laws are still being proposed and passed restricting freedom of movement, truncating the social rights of migrants, or making seeking asylum in Europe more difficult or even deadly.

This suggests that the classic jackbooted neo-Nazis that anyone could pick out of a lineup might not be the problem. Definitely a problem. But not the problem.

So what is? Two articles that we have recently posted, one by Walker of Permanent Crisis and the other by Lower Class Magazine’s Fatty McDirty, have proposed alternative ways of looking at both fascism and antifascism in their present-day forms, to help get us closer to the answer. It’s an insulting simplification of their arguments to put it this way, but “the problem” is that neofascism is not only created by neoliberalism (through the classic forces of economic victimization that prompt “Weimar” comparisons) but also embedded in its normal operation.

Walker’s and McDirty’s arguments diverge, but mostly they complement one another. In my reading, each argues in their own way that to defang neofascists we should prioritize resisting and removing neofascist characteristics from neoliberalism, even as we struggle meanwhile to overcome neoliberal capitalism itself. According to Walker, we must confront emerging economic nationalism and make the global economy more just. McDirty asserts that antifascists should broaden their focus, attack not only obvious nationalistic manifestations but also the elements of bourgeois democracy that contain the same destructive, misanthropic impulses, and work to build up defensible Left institutions and spaces.

Let’s do all of that! But how? I would propose we start by identifying the elements of real-existing neoliberalism that we consider fascistic, and at least begin calling them by their name.

Fatty McDirty warns against the inflationary use of the word “Nazi,” and we are used to these warnings by now. Most of us are familiar with Godwin’s Law. But first of all, we tend to apply it more broadly than is appropriate (erasing in the process important distinctions between Nazism and fascism). And second, in so doing we become accomplices to real fascists’ crimes against language, the acrobatic feats of syntax manipulation they have learned to use in order to avoid scrutiny and insinuate their racist, chauvinistic, dehumanizing and violent rhetoric into “civil” discourse without raising alarms.

I am becoming increasingly sensitive to the clear effect Godwin’s Law has on leftwing commentators irrationally obsessed with appearing rational. It is especially evident in audio formats, where I have heard, time and again, a righteous condemnation of the latest systemic outrage hurtling towards its inevitable payoff—only to have the speaker get stuck, “F” being such a malleable, versatile consonant, and pivot into a conclusion more acceptable in polite company: “…ffffffucking horrendous.”

For crying out loud, just say it! I have often induced laughter in comrades with my extensive usage of the word “fascist,” and I admit that throwing it around the way I do requires a gooey broadening of the term’s meaning that could occasionally be considered contextually incorrect. Walker invokes fascism “not as a term of abuse but as an analytical category.” But I would like to do both, and this requires expanding the analytical category.

If we want to speak precisely and differentiate carefully between various definitions of “fascism” across time and space, we still can and certainly should when it counts. But it is exactly because fascism has many faces in many places—as both Walker and McDirty point out—and because Godwin’s Law has become an implicit tool for silencing criticism (in an ironic reversal of the “PC police!” “Censorship!” epithets employed by many…ffffascists) that it becomes necessary and useful to cast a wider net.

To begin with, it’s about time we cast it back across the Atlantic. Up to this point in this essay, I have remained slouching in Europe, crowded in with the rest of the liberal Western commentators clutching their pearls about Golden Dawn, PEGIDA, Front National, and UKIP—or even Frontex, for the extra-sensitive. But it is important to recognize parallel phenomena on the North American continent.

Like Fatty McDirty, I think that the clearest examples of fascist ends being served by neoliberal means (and vice-versa) have to do with the politics of migration and refugees. McDirty lays out what this looks like in Europe:

“It is not PEGIDA demonstrators who travel to the Greek-Turkish border to save the Homeland from Syrian refugees. It is German police officers. It was not HoGeSa bar-brawlers who passed newly tightened asylum rules through German parliament, but the Green minister-president of Baden-Württemberg state, Winfried Kretschmann.”

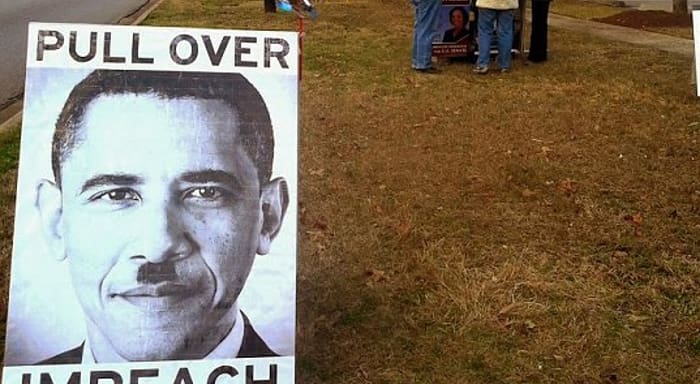

It is not difficult to find transatlantic analogs. The “virtual fence” and the migrant warehouses on the US-Mexico border are not projects of the Minutemen or of those sign-holding ladies in sun visors screaming “Go home!” at schoolbuses (who for some reason aren’t generally referred to as fascists either), but of a strange constellation of governmental and para-statal commercial entities operating on the fringes of legality. What does that sound like, already?

We should be condemning these and the long list of other violent, racist, nationalistic policies being carried out in the name of security at the borders of the United States “homeland.” We should be condemning the people calling for these policies and carrying them out. Many of us are. If the word “fascism” helps us do that (and I very much think it will, once it moves beyond its current use only by easily-dismissed solitary shriekers), then we should use it.

There are plenty of other terrifying phenomena worth emphasizing in the North American context which, I would argue, should also from now on be freely and fearlessly described as fascist. The prison-industrial complex in the US has recently exceeded, to much fanfare, the Soviet gulags in scale if not in sheer brutality (and that point can be argued). That this mass incarceration system has white supremacist origins and character is beyond dispute.

Inextricably linked to racist prisons is racist policing, which millions of people of color experience day to day as akin to living under occupation, or even counterinsurgency: constant surveillance, harassment, coercion, and straight up abduction, torture and murder at the hands of state authorities. And this is to say nothing of the explicit occupations and counterinsurgencies that the US military and “associated forces” are engaged in, overtly or covertly, all over the world.

And again, this is not the work of neo-Nazis or other titillating, visibly transgressive proto-fascists like the Ku Klux Klan (although people identifying with these and other radical rightwing groups are certainly present in the ranks of state institutions, private security and surveillance contractors, the military, and law enforcement). These things are produced—not only ignored or tolerated, but produced—by “bourgeois democracy,” by federal and state agencies established, staffed and funded by a government ostensibly representative of the US public.

And they are just the most obvious and extensively reported examples. If we get a little (but not much) more creative with the F-word, as I encourage, we’ll have to start admitting we see fascism in all sorts of places. My two favorite examples in the US are men’s rights activists and the charter school movement. It’s not too hard to call Elliot Rodger a fascist (though hard enough that most people don’t); it’s a little harder to say it about his online fans and co-misogynists but just as true. Calling Rahm Emanuel or Eva Moskowitz a fascist, on the other hand, seems to be the most troublesome of all for most people—even people who loathe their agenda—but that just makes it that much more provocative and potentially gestalt-switching. And no less true.

On a recent episode of a popular American radio show, the sound—or lack thereof—of charter school students single-filing out of class was recorded and broadcast, to the audible discomfort of the producer holding the microphone. She described having a “creepy feeling” as the eleven- and twelve-year-olds streamed by in total silence. That feeling, one we have all had in any number of analogous situations, is one we should begin to respect. There’s a reason for it, it has a name, and we should use it.

(Of course, the strict disciplinary structures being experimented with in some charter schools are not the only fascistic aspect of the movement to privatize education. Simply the most illustrative, perhaps.)

I would also be remiss not to mention the widespread homophobic and transphobic bigotry and violence which persists in the United States, both informally and formally, despite the significant and ongoing progress on the issue of marriage equality. In a way, this progress and the loud self-congratulation often accompanying it has made the life-ruining (and, sadly, often life-ending) repression still faced by gay, queer, and trans people less visible, and those who speak out about it less likely to be taken seriously. Calling their abusers—both personal and institutional, both physical and social—fascists might touch a nerve. So let’s do it.

But the elephant in the room is still Islamophobia. As is the case with refugees, people of color, prisoners, women, children, non-hetero or -gender-conforming people and any other marginalized group (it’s part of how we marginalize them), Muslims in the US get gaslighted—basically called crazy—when they talk about structural injustice, violence and threats of violence, and the fear they feel living among people who palpably hate them.

It’s no wonder they would hesitate to use the F-word; it wouldn’t “help their case” in the current rhetorical climate. My appeal to them would be to use it anyway. My appeal to readers who, like me, do not belong to any of these or other marginalized groups (the only readers I actually have any right to make appeals to), beyond simply listening to and trusting people who do belong to these groups, is to start hearing the F-word when they (don’t) say it.

It’s there. Fascism is there. The wolf that people are crying about is really there. In clear, unambiguous, demonstrable ways. There shouldn’t have to be a mass-mobilization of assholes equivalent to PEGIDA to shock us into that realization (and with any luck there won’t be). And when there is an incident of Islamophobic fascist violence like the one in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, this month (by far not the only such incident in the US in recent memory), we need to be able to connect it to other signs of rising fascism we have perhaps been ignoring, dismissing, or miscategorizing because “fascism” is something that only happens in Europe or some other such silliness.

A guest on a US podcast more respectable than the one I left nameless above did make these connections in an interview that turned into a grand yet understated, deeply uncomfortable, emotional and poignant monologue. In what I hope is not too hackneyed a symbolic gesture, I’d like to put my “ally” money where my mouth is and hand the mic to Ayesha Siddiqi, speaking on Radio Dispatch on 12 February 2015.

The following is merely a small selection of the important observations she made, which also clearly influenced this post. But I recommend listening to her entire statement, which you can do here.

Ayesha Siddiqi: For a lot of Muslims right now, it’s the moment we have all been holding our breath for, since part of the US war machine is the cottage industry of islamophobia that’s been outlined in reports like Fear, Inc., that was put out by the Center for American Progress. And this regular incitement to violence against Muslims is generally tolerated; it’s part of the news media.

Most minorities have experienced that wave of otherization, then the fear that those biases produce, and the subsequent highpoint of violence against them, and then this collective remorse: “Oh, gosh, we really shouldn’t have done that. We shouldn’t have put all the Japanese in internment camps! We shouldn’t have killed millions of Jews!”

The moment we’re living in now feels like a precursor to something of that magnitude. You would just hope that as a society, we can learn to watch out for the markers of rising momentum against a minority and you would hope that this time around we won’t let things get so bad.

As devastated as we are by this shooting, I can’t think of any Muslims who are surprised by it. These are certainly not the first Muslims I know of that have been killed because of a white person’s fears and anxieties about Islam, and I am afraid they are not going to be the last.

The feeling of being the subject of other people’s biases in a way in which your life is on the line, in a way which invites violence—there’s no way to really effectively communicate that feeling. It’s a feeling that black Americans, for one example, have felt throughout their history. And especially now, it’s something that’s been in the zeitgeist a lot more due to the effectiveness of social media campaigns behind Ferguson and the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag.

There’s this sense that the most basic of claims, that the right to life—a life free of fear, a life of dignity—is still what’s being negotiated for. And it’s disheartening that the community you live in doesn’t share your sense of urgency towards the protection of your life or the lives of people like you, or the people in your racial or religious background.

Young Muslims have just this sense of hopelessness that’s bred in you when you have police officers and FBI agents and the NSA in your mosque, trying to get you to incriminate your cousin or your uncle, or asking you questions about when was the last time you visited the country that your parents immigrated from. People whose Google search histories or Facebook statuses make them cause for suspicion.

The thing I always repeat online and elsewhere is, “whose ‘homeland,’ and whose security?” When you’re not the typical white guy, you’re pretty much constantly reminded, “well, not yours.”

The fact is, we should listen to the Muslims who have been trying to point out those patterns of violent incitement for years. For years. I mean, how many people wonder how many Muslims are going to get attacked now that so many young men, after watching American Sniper, left it tweeting, “We can’t wait to kill Muslims.”

We’re responsible for the environment that we allow to proliferate. So whether it’s a racist joke you’re letting pass without comment in your company, or a movie like American Sniper, which pretty clearly justifies the slaughter of Iraqi Muslims—look, we can’t control the actions of the unstable. But we also can’t be so naïve as to ignore the ways in which we’re complicit in the society that we live in.

There are things we can do to stop tolerating the hate directed towards Muslims. And it seems like that’s the least we can do, as long as Muslims are being slaughtered around the world, whether it’s by the Buddhists killing Muslims in Myanmar or the Muslim families whose cars are having grenades thrown into them in France, or the Muslims in England whose mosques are being burned down, or anyone who gets mistaken for being a Muslim in America who gets pushed off a subway train or gets shanked by the person that enters my taxicab, or…

It’s just this overwhelming sense of how absurd things have gotten. And it’s almost a sense of helplessness. I mean, what can we do that we haven’t already done? What remains to be done, for the reality of anti-Muslim bias and violence to be made visible to everyone else, to the rest of America?