Transcribed from the 17 December 2016 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

Our enemies from the past can be rehabilitated even as we continue to seek out new enemies in the present. The Japanese and the southeast Asians were evil years ago, but now they’re our allies and we can understand their humanity. Nevertheless new villains—Islamic radicals; Muslims in general—are completely beyond our comprehension.

Chuck Mertz: The origins of our wars can be found in the way we remember war. In fact, the way we remember war may have been the cause of past wars, and may be the cause of the wars we are involved in today. And the way we are currently remembering today’s wars may ensure more wars in our future.

Here to help us in our memory, to guide us through our remembering and forgetting, and to explain how both can lead to war, Viet Thanh Nguyen is the author of the National Book Award-nominated Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War. Viet is Aerol Arnold Chair of English and associate professor of English and American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. His novel The Sympathizer won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Viet.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Hi Chuck, glad to be here.

CM: It’s great to have you on the show.

You write that you were “born in Vietnam but made in America,” and you count yourself both among those Vietnamese “dismayed by America’s deeds but tempted to believe in its words,” and among those Americans who do not know what to make of Vietnam and want to know what to make of it.

“Americans as well as many people the world over tend to mistake Vietnam with the war named in its honor (or dishonor, as the case may be). I’ve spent much of my life sorting through this confusion, and the most succinct explanation that I’ve found about the meaning of the war, at least for Americans, comes from Martin Luther King Jr.”

Then you quote King saying, “If America’s soul becomes totally poisoned, part of the autopsy must read, Vietnam.”

How much of that poison of Vietnam still lingers in the US today? How much does that war still have an adverse, even sickening effect on the way the government acts and the way US citizens and culture view and relate with the greater world?

VN: It’s still there, and it’s in increasing evidence. In the few decades after the end of the Vietnam war, the negative experience for Americans was the predominant feeling that a lot of Americans had (and a lot of the world had as well) in the memory of the war. That’s why, from the mid-1970s through 1991, the US was really reluctant to get involved in imperial adventures overseas.

But since the Gulf War, from ’91 up to now, there’s been an increasing effort on the part of the government—the White House, the Pentagon, the military industrial complex—to transform how we remember the Vietnam war from something negative into something positive. This is a bipartisan effort. Republicans and Democrats, including president Obama, have sought to recast the war as a noble (if failed) endeavor in which the United States was sacrificing lives in order to liberate the Vietnamese and to defend American values.

That has become increasingly competitive with the more negative memory that we had of the Vietnam war, and we see it being implemented in American military strategy. We see it in that American military officers look back on the Vietnam war and try to extract positive lessons, how to fight wars better as a result of what they see in the Vietnam war.

CM: Can any nation’s citizens, though, look at a war in a fair fashion? Folks in the United States may view the war that took place in Vietnam in a more positive light than they should. But isn’t that a blind spot for any nation’s citizens?

VN: Absolutely. One of the main points of the book is to look at the different ways different countries have remembered this one war, the Vietnam war. And you’re right. If you only look at an event, for example this war, from one nation’s point of view, it’s very often the case that you get a lopsided perspective.

Growing up in the United States, and seeing how Americans remembered this war, I definitely felt that this war was incredibly important for Americans, but it was also a war that Americans saw purely from their own point of view. And as someone who is Vietnamese and who was experiencing how southern Vietnamese refugees saw this war, I saw that there was a distinct difference.

This didn’t make the southern Vietnamese point of view any “better.” It was just different. One of the things that I have really had to struggle with throughout my life has been the question of how to see a deeply divisive event from multiple points of view. It was important for me to write a book that addressed not just how southern Vietnamese people saw the Vietnam war and how Americans saw it, but also how the victorious Vietnamese see it.

If you go to Vietnam, it’s a very one-sided perspective—this was a victorious war, a triumphant war, a noble war—which completely obliterates how the losers, the southern Vietnamese in particular, saw it. It’s incredibly important for us, as we look at war, to understand that we need to see it from the perspectives of our enemies and from the perspectives of the losers as well.

That’s how Martin Luther King Jr. saw it in his speech “Beyond Vietnam” that I quote at the beginning of the book. It’s an incredibly important speech. It was a speech that emerged out of his increasing radicalization in 1967 and 1968, and it was a perspective where he was trying to empathize with the “enemy,” with Vietnamese people. I think it was a perspective that contributed to his eventual assassination.

CM: Here’s King: “The war in Vietnam is but a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit. If we ignore this sobering reality, we will find ourselves organizing Clergy and Laymen Concerned committees for the next generation. They will be concerned about Guatemala and Peru; they will be concerned about Thailand and Cambodia; they will be concerned about Mozambique, South Africa. We will be marching for these and a dozen other names, and attending rallies without end, unless there is a significant and profound change in American life.”

Clearly we haven’t seen that change. What do you think is the deeper malady within the American spirit that concerned King? And are protests like the antiwar protests in 2003 (that were the world’s largest ever) a sign that indeed King’s warning were not heeded? We’re still marching, a generation later, against wars overseas.

VN: Yes. The speech that he gave was prophetic. Of course, the speech that Americans mostly remember is “I Have a Dream.” So we have a Dream, which confirms the American Dream, versus a Prophecy, which most Americans would rather ignore—or simply don’t even know about, because our entire society is built to not transmit the vision that Martin Luther King Jr. had by 1967. That vision was prophetic because the structural problems that he identified in 1967 are still with us.

What he was arguing in that speech was that we can’t understand American inequality at home—our deep-set problems of class and race and discrimination, and the exploitation of the poor and working class of all colors—if we don’t see how it is made possible by a military industrial complex that engages in foreign adventures and was (at that time, from King’s point of view) conducting an imperial war in Vietnam…which was also a racist war directed against other people of color, and which the United States was sending its own people of color to fight.

That connection between the domestic and the foreign that King was making was a radical insight that made him a lot of enemies, and it alienated a lot of his allies as well. Many of his civil rights allies did not want him to make that speech, they did not want him to make that connection. They feared that if he did, American public opinion would turn against their efforts to address racial and class inequality at home.

And the desire to make that connection is still a dangerous one. It’s still difficult for Americans to see how what happens at home is connected to what happens abroad, which is why so much of the recent presidential campaign tried to sever that connection.

CM: How much of Americans’ understanding of a war like the Vietnam war is undermined by the desire to have a narrative in which there are Bad Guys and Good Guys?

VN: I think that’s universal. It’s not unique to Americans. If we look back at our past (as well as, obviously, at our present), the temptation to see the world as Us Versus Them, Good Versus Evil (where we’re Good), has been predominant throughout American history. It allowed us to justify the kinds of wars we conducted in expanding the American frontier westwards, over Indians and Mexicans, all the way to the Pacific. It still allows us to see the world in a very moralistic and simplistic fashion.

This is another narrative that is exploited in a bipartisan fashion. Whenever we conduct foreign policy adventures overseas, this idea is propagated that we’re on the side of Good, that as Americans we’re Exceptional, that the United States is an Inevitable Force for Morality and that everybody should imitate us. That’s something that both Democrats and Republicans believe in very strongly, and it percolates all the way down to the electorate, to the average person. When Donald Trump says Make America Great Again, and say that he’s on the side of the average (Good) American, he’s appealing to that narrative as well.

There’s a lot of work to be done to get people to see the world beyond that.

CM: You write, “When it comes to war, the basic dialectic of memory and amnesia is not only about remembering and forgetting certain events or people. It is instead more fundamentally about remembering our humanity and forgetting our inhumanity, while conversely remembering the inhumanity of others and forgetting their humanity.”

So over time, do the Bad Guys always get worse and the Good Guys always get better in a nationalist perspective of history?

VN: I think it depends. That basic idea that we’re Good and they’re Evil remains with us. It’s just that who is Evil changes over time. Clint Eastwood sort of embodies this binary view of the world—he made Letters From Iwo Jima, which humanized the Japanese, and then a few years later he would go on to make American Sniper, which demonized the Iraqis. In between, he made Grand Turino, which humanized the Hmong, these Asian refugees in the United States. How did that happen?

Our enemies from the past can be rehabilitated even as we continue to seek out new enemies in the present. We fought wars with the Japanese and with the southeast Asians—they were Evil fifty years ago, but now they’re our allies and we can understand their humanity. But these new villains—Islamic radicals; Muslims in general—are completely beyond our comprehension. The binary remains the same, but who we think of as evil changes.

Maybe he’s a little haphazard about it, but nevertheless Trump understands that Twitter is a propaganda machine, that you can shape fantasies through it.

CM: Is it possible to make a movie about war that doesn’t glorify war?

VN: For many people—universally, but especially for Americans—“war” means guys in tanks and airplanes or guys carrying guns fighting somewhere in a battlefield; there are clearly delineated distinctions between soldiers and civilians. That’s not really what war is, at least not from my perspective. That’s a very contained understanding of war.

When I think of war, I think of the military industrial complex. I think about how all of us are implicated in the war machine because we pay taxes; we are complicit because we vote, because we don’t do anything. And war is actually really boring. The exciting part of war is seeing combat, and that’s why young men, who know war is hell, still go off and fight in wars—because it’s exciting.

War is actually really boring; war is systemic; it involves all of us. That’s the part that we don’t want to think about. So if you want to make a true antiwar movie, you don’t make Apocalypse Now. Apocalypse Now may be, on the surface, an antiwar movie, but it gets everyone revved up. In the memoir Jarhead by Anthony Swofford (and in the movie adapted from it), Apocalypse Now is shown to young marines in training, to get them pumped up for war.

A true antiwar movie would show us how boring war is; it would show us soldiers coming back from war and killing themselves, suffering from PTSD, becoming homeless, abusing their spouses, turning their children against them—but that would be an antiwar movie that nobody would really want to see.

Even if a movie says war is hell (and Apocalypse Now clearly says that), if it also shows how exciting it is to shoot rockets and fire machine guns and blow up the enemy, that dimension of the war story—the one that gets us excited—can trump the explicit moral message that war is hell. Those of us who are artists and writers have to be really conscious of how we tell stories in addition to the content of the story itself.

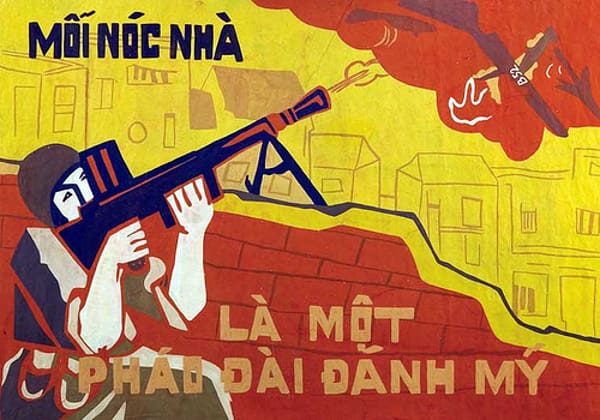

CM: You write, “Art is crucial to the ethical work of just memory. After the official memos and speeches are forgotten, the history books ignored, and the powerful are dust, art remains. Art is the artifact of the imagination, and the imagination is the best manifestation of immortality possessed by the human species, a collective tablet recording both human and inhuman deeds and desires. The powerful fear art’s potentially enduring quality and its influence on memory, and thus they seek to dismiss, co-opt, or suppress it. They often succeed, for a while. Art is only sometimes explicitly nationalistic and propagandistic; it is often implicitly so.”

When I think of art relating to the US war in Vietnam, the first thing that jumps to mind is Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial (as it is officially known) in Washington, DC. Do you see any explicitly or implicitly nationalist propaganda—potentially pro-war propaganda—in the Vietnam Veterans Memorial?

VN: It’s a beautiful and powerful memorial, and like all great works it invites multiple readings and multiple ways of relating to it. Certainly one dimension that is powerful for many people is that it’s a place that invites mourning and remembrance of the American soldiers that had been lost, and the impact of those lost lives on their families and on the entire country.

Yet at the same time it’s important to think about what is absent or forgotten in that memorial—and in every memorial. All works of memory ask us to remember something, but implicitly allow us to forget things as well. That’s absolutely integral to every work of memory. In the case of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the explicit purpose is to get us to remember the 58,000-plus American soldiers who died in that war. But what is absent? The invisible background is the fact that millions of southeast Asians also died in that war.

Depending on how you divide up the period of the Vietnam war—what countries it took place in, whether it began in 1964 or 1954 (or 1945) and whether it ended in 1975 or the 1980s—anywhere from three to six million southeast Asians died during that war. Most Americans don’t have any sense of this. They know that a lot of Americans died, and they have a sense that southeast Asians also died, but they don’t understand the vast scale of discrepancy between these things.

Jimmy Carter said in 1978 that this was a war of mutual destruction—it absolutely, factually, was not. But the Vietnam Veterans Memorial has been deployed by presidents and by veterans to foreground American losses and allow us Americans to forget the Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian deaths during that war.

CM: How much do you see that kind of forgetting in Vietnam war movies? You were talking about Apocalypse Now earlier; The three other movies that I think had the most cultural impact—Full Metal Jacket, Platoon, and Good Morning Vietnam—do all these movies fail in depicting the Vietnamese as participants on the war by focusing only on the people from the United States, on the glory and the heroism of the US soldiers, and not on the inhumanity that took place during the war?

VN: The blunt answer is yes. Obviously these movies do depict Vietnamese people, sometimes with some degree of sympathy, but the main function of Vietnamese people in these movies is to be killed, raped, or rescued. They don’t really get to speak at all. Even in Good Morning Vietnam, where the Vietnamese are depicted more sympathetically and they actually get to say some stuff, their major function is to be rescued and to help Americans feel better. They’re not really rendered as full subjects in the way that American soldiers or American civilians are.

In that way, what these movies do (along with the overwhelming bulk of American memory about the war, whether we’re talking about novels or journalistic reports, political treatises or history books) is foreground the American experience and American subjectivity, where the Americans are the major actors in this war. Even though, again, most of the people who died in this war were southeast Asians.

Going back to your earlier questions, this is a very important way by which we get a one-sided view of history from the American perspective. And while this is completely normal and happens in other countries as well, the danger is that by doing this we repeat the same cultural mindset that got us into the Vietnam war in the first place: the mindset that the world is built around the United States; the American point of view is the most important and we really don’t need to understand what other people think; we can go into foreign countries and do what we want; and things will turn out the way we expect.

That didn’t happen in Vietnam, didn’t happen in Iraq, didn’t happen in Afghanistan, and part of the reason is that the stories we tell ourselves as Americans just repeat the American point of view back to us. This continues to reaffirm the idea that we are the heroes of our own story; we are heroes of our own foreign policy endeavors—and even when we’re not, even when we’re anti-heroes (as is the case in most of these Hollywood Vietnam war movies wherein the American soldiers do bad things), we are nevertheless still the center of our own story, and that’s the most important thing. We don’t ever want to be the extras or the silent people in these movies or in the stories that we tell ourselves.

As long as we do not understand that other people’s and other countries’ points of view need to be taken into consideration and given equal weight, we’re never going to understand how other countries, other cultures, and other peoples may see our actions in a radically different light than we do.

For example: drone strikes. From the American point of view, drone strikes are technologically rational—they don’t kill very many people; they are supposedly surgical. Why wouldn’t anybody support the use of drone strikes? Fewer people die. But from another country’s point of view this is a war crime. It’s an intrusion on sovereignty. It’s the death of innocents. It doesn’t really matter whether you kill ten innocents or a million innocents. The fact that you kill any innocents is horrible. And if that were being done to the United States, even if only ten Americans died, we’d be going to war over it. But we really don’t understand other countries’ reactions to these policies, because we can’t imagine it happening to us.

Obviously a substantial portion of Americans do get a sense that we should not be doing drone strikes, that we should not be sending troops into other countries or have 800 or 900 military bases overseas. But another substantial portion of the American population, including many of those in power, don’t see it as a problem. They see this as a rational exercise of American foreign policy and American military power, and imagine that this can be done in a moral, just, and humane way.

CM: I want to ask you about something that I saw on TV last night, a very heartwarming news story about a GI who had come home, was homeless, and a whole bunch of people put some money together and bought him a home. It was a very touching holiday news story. But I couldn’t help thinking that the story was, in a way, pro-war.

Is there implicit pro-war propaganda (if you will) in news stories like that?

VN: I think so. When we say the word propaganda, we think that’s what the Nazis did—that’s what the Soviet Union did; the Chinese, the North Koreans, the Russians today—without understanding that we as a society produce propaganda too. Except that we produce really good propaganda. We produce propaganda that we don’t know is propaganda, because we live in a supposedly free society.

In reality, though, how propaganda works in this country, as in any other, is through ideology. Most of us agree that America is a great country and that we have the freedom here to tell the stories that we want. But we still mostly tell stories that fit our point of view. When we tell stories about American soldiers—heartwarming stories about how brave or courageous they were or what good people they are when they come home—it implicitly affirms this goodness of Americans and does not comprehend one of the most difficult truths out there, which is that we are all capable of inhuman behavior and that, as a matter of fact, inhumanity is a core part of our humanity.

I say this is universal because it is true in every country. People don’t want to recognize the inhumanity that is necessary for us to go out and fight wars. American soldiers, yes, they are good people—but when we put them into foreign places with a lot of firepower, they are going to do some terrible things. And when they come home, we don’t want to remember or even acknowledge that those terrible things might have taken place.

The narrative of supporting our troops even if we oppose the war is one of the most effective acts of propaganda that the United States has come up with in the years after the Vietnam war.

People all over the world still see the Vietnam war through the eyes of American soldiers, because the American war machine, the most powerful war machine on the planet, is paralleled by the American memory industry, which is also the most powerful on the planet.

CM: You write, “Both memory and forgetting are subject not only to the fabrications of art but also to the commodification of industry, which seeks to capture and domesticate art. An entire memory industry exists, ready to capitalize on history by selling memory to consumers hooked on nostalgia. Emotion and ethnocentrism are key to the memory industry as it turns war experiences into sacred objects and soldiers into untouchable mascots of memory.

“Critics see this memory industry as evidence that societies remember too much, transforming memories into disposable and forgettable products and experiences while ignoring the difficulties of the present and the possibilities of the future. But this argument misunderstands that the so-called memory industry is merely a symptom of something more pervasive: the industrialization of memory.

“Industrializing memory proceeds in parallel with how warfare is industrialized as part and parcel of capitalist society, where the actual firepower exercised in a war is matched by the firepower of memory that defines and refines that war’s identity.

“The technologies of memory and warfare depend on the same military industrial complex, one intent on seizing every advantage against present and future enemies, who also seek to control the territory of memory and forgetting…

“The memory industry produces kitsch, sentimentality, and spectacle, but industries of memory exploit memory as a strategic resource. Recognizing that…enables us to see that memories are not simply images we experience as individuals but are mass-produced fantasies we share with one another.”

If humanity now believes in mass-produced fantasies, prior to mass media, who produced the public’s fantasies? Or do you believe that people used to believe in fewer fantasies than they do today?

VN: Obviously we’ve always believed in fantasies. Every society, every age produces fantasies in a different fashion. But we’re really living in a different era now with mass media of various kinds, and social media, where our mass fantasies are transmitted in ways that would be just mind-blowing for someone only a hundred or two hundred years ago.

There are clearly some individuals who are very conscious of how to produce fantasies. These are the people who are good at propaganda, who understand how the mechanisms of memory and representation work, and they deliberately fashion stories that get people to think in a certain fashion. I think Donald Trump does that. I think he’s very conscious of shaping narratives in a certain way. Maybe he’s a little haphazard about it, but nevertheless he understands that Twitter is a propaganda machine, that you can shape fantasies through it.

Most of us, though, are much more naive about how this works, and we simply consume the fantasies and participate in the fantasies that are given to us when we consume mass media. This is how people reflexively, innately believe in certain kinds of stories about American culture, the American Way, American Exceptionalism. Thus when terrible things happen, like 9/11, we are immediately ready to participate in a mass-produced fantasy about Us Versus Them, and we have to go to war even if we’re going to war with the wrong country or the wrong people. Meanwhile the people who really understand how to manipulate these stories are manipulating them exactly in order to get the American population behind the action that they want to take.

CM: So how much has the US acted out based on a false memory, a fantasy of Vietnam? Since 1976, what have you seen that would indicate to you that the US has acted out based on a false memory, a fantasy of Vietnam?

VN: I can think of at least two important fantasies. One fantasy that Americans like is that wars are discrete. The Vietnam war began in 1964 and ended in 1975. That’s an American fantasy. It’s simply not true. The Vietnam war began before that, and it went on for a long time after that, for a lot of people.

The greater problem with viewing the Vietnam war as discrete is that it is also embedded in American society as a function of this military industrial complex; it’s only one episode in a longer history of warfare that goes at least as far back as 1898 (with the United States going to the Philippines), and arguably before that, to the Mexican-American war and the Indian wars. The United States has been fighting a war of expansion since at least the nineteenth century, and it’s going on today. That’s what the fantasy of the discrete Vietnam war obscures.

The other major fantasy is that we go to war for good reasons. Americans deeply believe that. That’s a major fantasy. Whereas my personal viewpoint is that this is the mass-produced, propagandistic fantasy that we like to spread around to get Americans to agree to war. In actuality the agents of war—the people actually instigating these wars and making the decisions to go to war—are getting us to go to war for very strategic political and economic reasons concerning American power and American profit. But you really can’t tell that story to the American population. You have to tell the American population a fantasy that we’re doing these things in order to either defend America or rescue other people.

CM: So is it not the victors, then, who really write the history, but the nation with the strongest industrial memory?

VN: I think generally that’s true. One of the points that I make is that Vietnam won the war in fact, but it lost the war in global memory. Wherever you go in this world, whenever you bring up the Vietnam war—at least when I do—people remember the American perspective, generally, of the Vietnam war.

The only hope I have in that regard is that at the same time that they remember that, they also remember that it was a terrible war. The legacy of the conflict is still there, present in the global memory. But it’s overwhelmed by this sense: people all over the world still see this war through the eyes of American soldiers because of the power of the American story. And that is because the American war machine, the most powerful war machine on the planet, is matched by the American memory industry, which is also the most powerful on the planet.

It’s no surprise, because they both emerge from the same capitalist system. This is the way by which the United States has been able to write the history of the war through its industry of memory.

CM: That leads us to our last question, Viet. It was going to be, Who won the Vietnam war? But I guess it should be, Did anyone win the Vietnam war?

VN: I think capitalism won the Vietnam war. If we cut off the Vietnam war in 1975, then we can clearly say Vietnam and its allies, China and the Soviet Union, won that war. The Americans and the South Vietnamese were defeated. But if you understand that war is not simply the eruption of combat but it’s a much larger campaign for victory by entire societies and systems, then it would seem that capitalism won.

That was what the United States fought for—not simply to defend democracy, but to stop communism and to create a safe space for capitalism in the Pacific. The years after the Vietnam war speak for themselves: that’s exactly what happened. Vietnam is still run by a Communist Party, but it is in effect a capitalist society that is now very receptive to American influence and American partnerships. Forty years after the Vietnam war, the ironic outcome is that essentially capitalism has become victorious in southeast Asia.

And what we’re seeing today in the South China Sea is not really a conflict between Capitalism and Communism, as America and China face off there, but a competition between differing and competing visions of capitalism as run by two different countries competing for global domination. In that sense, the Vietnam war was simply a prelude to what we’re seeing today, this much larger war over which country is going to dominate globally.

CM: Viet, I really appreciate you being on the show with us this week. I can’t thank you enough.

VN: Thanks so much, Chuck, it was a great interview.