Transcribed from the 25 February 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

The US government and US government agencies have often tended to identify expertise that reflects their own interests and their own perceptions of this region. Some scholars will be promoted and endorsed and will get funding, and other scholars will be ignored or their studies will be minimized.

Chuck Mertz: How did US policy in the Middle East become what it is today? How did we get to a point where thinktanks are controlling policy debates while attacking academia for studying the same? How does our foreign policy and national security establishment view the Middle East, and why?

Here to help us understand the context of US policy in the Middle East, historian Osamah Khalil is author of America’s Dream Palace: Middle East Expertise and the Rise of the National Security State. He is assistant professor of US and Middle East history at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Osamah.

Osamah Khalil: Thanks Chuck, happy to be here.

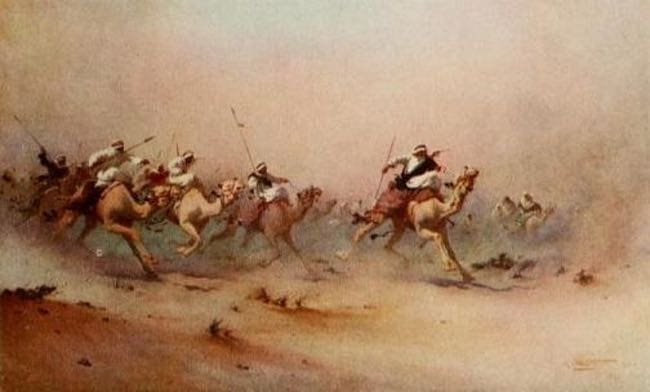

CM: You quote T. E. Lawrence writing on the Middle East: “I meant to make a new nation, to restore a lost influence, to give twenty millions of Semites the foundations on which to build an inspired dream-palace of their national thoughts.”

Then you write, “Orientalists and area experts, modernization theorists and national security academics, nervous liberals and neoconservatives: they all sought to make—or remake—the Middle East in America’s image based on their hopes, fears, and illusions.”

How much do you believe that illusion is a foundation for the understanding people in the United States have of the Middle East? How much is our Middle East their illusion?

OK: I think there are a couple things to unpack there. One of the things I focus on in the book is how policymakers view the region, and how this influences academics and the academic study of the region. Much of what the general population knows about this broad area we call the Middle East is often driven by those foreign policy interests.

What is the Middle East? Where is the Middle East? Most Americans probably can’t tell you where they would draw that line. Where does the Middle East begin and where does it end? It’s really driven by what US interests are (Is it oil? Is it stability in this broad region? Is it protecting Israel?). Washington policy wonks always talk about “security and stability,” over and over again.

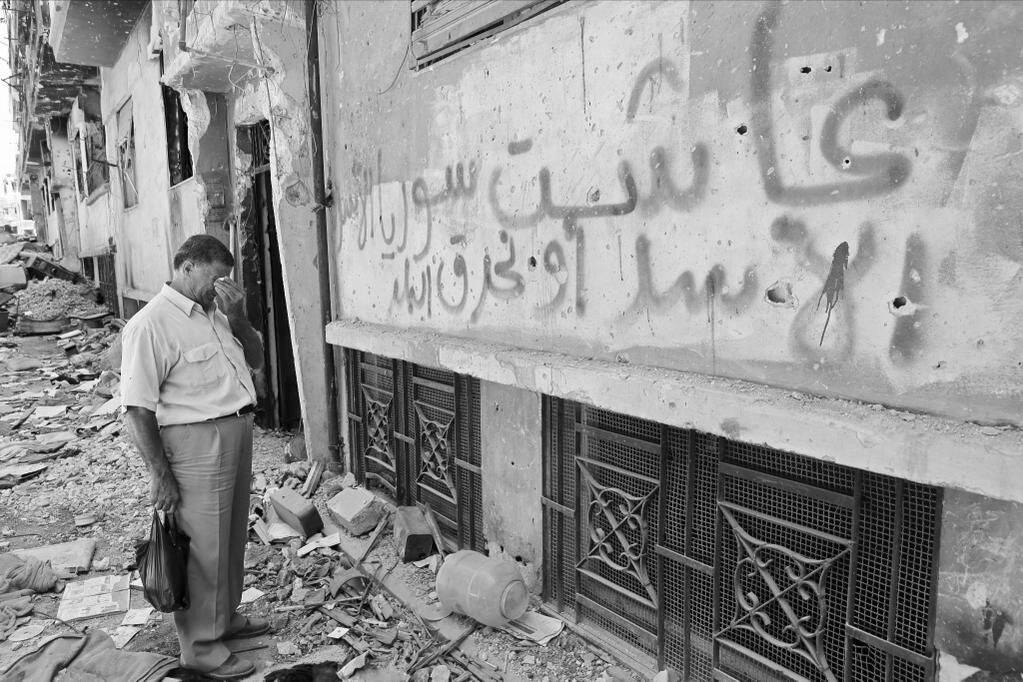

So I trace that out over the past century: how did the United States become involved in this area? Often initially through missionaries, and occasionally through the search for oil resources. That expands with the post-World War Two era up to today, where we’re deeply enmeshed in the region, fighting several overt and covert wars, where we fund and have close ties with a variety of different states in the region (whether it’s Israel or Turkey or any of the Arab Gulf States) and often contentious relationships with others (Iran, Syria and a number of non-state actors).

To get back to your question, much of what the general public knows about the Middle East is driven by and filters down from how policymakers have shaped it in the public perception. It’s often viewed as this area of constant turmoil, full of people who are projected as hostile towards the United States. This framing doesn’t really help us understand the area or the interests that are really driving policy.

CM: I hate to be repetitive, but it just seems amazing to me that our understanding of the Middle East is driven by illusion. It seems like our government is intentionally telling us a lie or a fabrication about the Middle East, and that’s leading us to have bad opinions about the Middle East.

How much are our bad opinions of the Middle East, and our bad decisionmaking when it comes to dealing with the Middle East, based on this illusion, this fabrication?

OK: A great deal. Let me take a step back, and let’s talk about this area, the Middle East. This term was originally invented in relationship to British interests in the region. The “Middle East” at the turn of the last century encompassed India and its surrounding territory. The term was coined by an American naval strategist. He divided the “Orient” up into a Far East (what we would think of as China and Japan), a Middle East (which we would think of as India and its surrounding areas) and a Near East (what Americans now call the Middle East—the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa).

One of the things I try and unpack is that shift in this area called the Middle East, how much it reflects, initially, America’s Cold War interests (America becomes deeply enmeshed in this region during the Cold War, especially the late Cold War period) and how we see these boundaries fluctuate. How does Pakistan, or Afghanistan, become part of the Middle East? How do the Central Asian republics that used to be part of the Soviet Union become part of the Middle East? Where does North Africa end, where does it begin, and where does the Middle East end and begin? And how does that relate to America’s increasing interests there and its drive to secure global hegemony?

When we talk about how most Americans think of or understand the Middle East: most Americans don’t. They don’t really understand where the Middle East is or what our interests are there. So many of them will just reduce it down—especially today—to oil and terrorism, and maybe a third point, our close alliance with Israel. And that really doesn’t help us. It doesn’t really get us to understanding what US interests are there.

For example, something I’ll talk to my students about is how much oil the US actually gets from the Middle East, how much it produces domestically, and how much comes from our neighbors in Canada and Mexico. My students, much like a lot of Americans, are shocked when they see the raw numbers. But this isn’t really about the oil that the United States needs itself. The United States and England in the post-World War Two area declared that they were going to be the global guarantor of oil supplies. Nobody asked them to do it. They declared that they would be. So it isn’t about oil as much as it is about power. It’s about securing a vast number of American bases that allow the United States to project power around the world. And the Middle East is a central fulcrum in that.

CM: You contend that the “emergence of Middle East ‘expertise’ reflected the US’s national security interests in the region and globally,” as you’ve mentioned a couple times already. Has the study of the Middle East in the US always, then, been done through a lens of US national security interests? And is that unique? For instance, if I am studying Serbian area studies in France, do I also look through a lens of national security interests for France?

OK: Part of the argument comes out of how this area we’re calling the Middle East was studied by European powers. This was unpacked by Edward Said in Orientalism, this idea that the study of these foreign areas really reinforces imperial concerns. For the United States, much of that is adopted. What used to be known as “Orientalism” has been adopted. Many of the original Orientalist scholars—I’m talking about the turn of the last century—were trained in the British, French, or German traditions, so they bring a number of those skills with them, as well as their biases.

But there’s not one monolithic tradition. The US government and US government agencies have often tended to identify expertise that reflects their own interests and their own perceptions of this region. Some scholars will be promoted and endorsed and will get funding, and other scholars will be ignored or their studies will be minimized. By the late Cold War period, of course, we get the rise of thinktanks and this symbiotic relationship between the thinktanks (who want to serve the foreign policy establishment) and the foreign policy establishment itself (which is looking for academic respectability and for the people who do the studies to have the kind of academic credentials that they’re having difficulty getting).

We also want to think about how Middle Eastern studies have often been viewed inside of academia and outside academia. I try to challenge the notion that somehow Middle East studies are unique. I try to link it to the study of Russia or the Soviet Union, Latin America, or East Asia—areas where the United States had really deep Cold War interests, and that influenced their study of those regions. The development of Middle East expertise in the United States over the past century has been very similar to these other areas where the United States is either seeking to contain Soviet power, understand its Soviet enemy, or contain Communist China and understand its Communist Chinese enemy.

By cutting funding to area studies, what we’re effectively doing is reducing what we know about other areas of the world. Some people are going to argue that this hurts our national security—but not everything is about national security.

So I think it’s important for listeners to understand—and then hopefully they’ll read the book—how much of this is driven by expanding and growing interests not just in the Middle East but globally. America’s interests in the Middle East increased over the past century, and with that came the expansion of funding or restrictions on study of the region, and the embrace of thinktanks and the revolving door.

There are a couple different trends that go on. On one level, what the government wants is people. What they’re hoping universities are going to do is train raw recruits: people with a basic understanding of the region, some basic language skills, who will then be institutionalized within federal government agencies. They still maintain that. Those people are going to come from all the basic universities. From that perspective, federal funding of area studies and language studies has worked. They get that base knowledge. And then the government agencies—the State Department, CIA, etcetera—have their own training.

A real pivot point is, of course, the Vietnam War. Federal government agencies, and in particular the intelligence agencies, become increasingly uncomfortable and are finding increasing resistance from scholars in universities to an open alliance with government agencies. This wasn’t the case for the first two decades after the end of World War Two. There really were open relations in the early Cold War, in which universities are literally saying to the intelligence agencies, “Tell us what you’re interested in and we will structure research programs around it.”

By the late sixties and early seventies, there are increasing campus protests and increasing division between academia and the rise of the New Left on the one hand and government agencies on the other. The government agencies are very well aware of this and are tracking this. But their needs have also changed. The CIA in the late 1970s and its needs are quite different from the CIA in 1950. It’s much more professionalized. They have built a massive apparatus of signals intelligence, so they’re getting in a lot of information that they weren’t getting in the late forties and early fifties. They have much more specialized needs, so they do effectively two things: they align with the thinktanks (who are quite happy to do the types of research that they want), and they do much more targeted consulting arrangements with academics. It’s no longer the broad sweep that they’re interested in. They are looking for people who are happy to do the kind of research they want on a contract basis.

CM: Could area studies exist without government assistance? Before government assistance of area studies, there weren’t many area studies going on. How much are area studies dependent on government subsidies?

OK: There is federal funding of what they call national resource centers, where there is language study, there is area studies, there are fellowships for graduate study and also for undergraduate study of languages. Government funding usually accounts for as little as ten percent of the actual operation, but it’s often more once we count fellowships and additional money that comes in. Universities are expected to match that—not just to rely on government funding, but also to fundraise more. This effectively forces a trimming down. It’s cuts down on the number faculty that can teach these classes and the number graduate students who can become trained.

At the height of the Cold War, with this amazing existential threat that the Soviet Union represented, when the federal government wanted to start implementing funding for area studies and language it did not put a requirement that if you took money from the federal government (if you took one of these fellowships or scholarships), that afterwards you had to go work for a national security agency. That doesn’t start until after the Cold War.

After the existential threat is gone, all of the sudden we started tying the study of regions and the study of language directly to national security, and the requirement that you have to serve in a government agency, particularly one of the national security agencies. Funding even increased, post-9/11. But there’s this idea that after 9/11 the government dumped a ton of money into the study of Arabic, and that’s actually not true. Funding increased, but not enough to keep up with this massive demand. The number of students taking Arabic increased in some cases by two hundred percent in the space of four or five years, and funding did not keep up with that. And area studies had been underfunded for nearly a decade before, if not more.

By cutting funding, what we’re effectively doing is reducing what we know about other areas of the world. Some people are going to argue that this actually hurts our national security—but not everything is about national security. We are a rich enough country that we can have vibrant universities that are not begging for money from corporate funders or rich donors. This is a very rich society. When we look at the amount of money we’re actually talking about, it is a drop in the bucket when you compare it to our massive military programs.

CM: I just want to go back and touch on Edward Said’s Orientalism. You write, “Edward Said’s seminal work, Orientalism, critiqued the discipline as well as the ideology it represented. Said argued that the notion of the “Orient” was an invention of the Occident—Europe and the United States. He asserted that Orientalism reproduced and served to justify the imperial policies of Britain and France. This relationship to imperialism, Said explained, gave orientalist discourse its power and ensured its durability.”

How much do you think Orientalism still guides American thinking on foreign policy in the Middle East?

OK: It’s huge. It’s still very relevant. You can trace that from the Woodrow Wilson era all the way through the presidency of Barack Obama, and of course to today, with the travel ban. This discourse is so prevalent and so rich and so powerful. It is so influential on so many levels, whether it is overt orientalism and overt racism as we saw with the travel ban, or whether it is much more latent forms like we see repeated throughout popular culture. There is a whole slew of TV shows we could talk about in terms of how the Middle East is represented and reproduced. Of course Said touches on some of this not only in Orientalism but in his book Covering Islam.

Everything from a show like Homeland to a show like Quantico—and we even see it showing up in shows like The Wire, how The Wire refers to the Middle East in reference to Baltimore. It’s very powerful, it’s very important, but it’s understated. What I try to show is that Orientalism directly influenced foreign policy before the Cold War (before the United States had real dramatic national security interests in this region), during the Cold War (when it became much more involved in the area we call the Middle East), and post-Cold War (of course with 9/11 and afterwards).

We opened the interview talking about T. E. Lawrence and Lawrence of Arabia. Lawrence plays this fascinating role in how American policymakers and government officials view this area called the Middle East and view the “Orient.” One of the things I talk about in the book is World War One, and the influence of his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom on scholars of World War Two who were selected to go to the Middle East as part of the OSS (the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the CIA), who were told: “We’re going to send you to the Middle East to fight the Nazis; you’re going to to be the Lawrence of your generation.”

And then Lawrence reappears after 9/11; he’s embraced by counterinsurgency experts who are now struggling with how to fight insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan. Somehow they decide that T. E. Lawrence is an example of a counterinsurgency expert—the original counterinsurgency expert, as some embrace him—and say, “This is a guy who understood ‘the Arabs,’ understood ‘the Arab mind,’ and can give us real cultural insights into how we can develop a counterinsurgency.” This has nothing to do with reality, and yet that’s the way he’s embraced. Most scholars view Seven Pillars of Wisdom as a work of fiction. If you go to Barnes & Noble today, right now, you can find a copy of Seven Pillars of Wisdom in the fiction section. That’s exactly where it belongs. It’s a wonderful work of fiction, beautifully written.

Many of those World War Two scholars, those guys who thought they were going to be the Lawrence of their generation, came home from the war and desperately tried to write their own versions of Seven Pillars of Wisdom, hoping to be the new Lawrence, and none of them were able to do it.

Orientalism is amazingly persistent. It is amazingly consistent in the way it represents this area and the people who are there. It is pervasive in popular culture. We see this in the 1970s, tied to the oil crisis; in the 1980s—think of Back to the Future, right? Who were the bad guys in Back to the Future? Libyan terrorists. How are they represented? You never see their faces. Their heads are covered. They are just maniacs shooting things up. And of course there is post-9/11. And in between, there are a number of cultural artifacts that we can pick at, whether it’s Arnold Schwarzenegger in True Lies or Aladdin from Disney.

We actually hurt ourselves, and we hurt American society, when we continue to allow these kinds of racist sentiments and the basest most xenophobic elements in society to be empowered.

CM: Edward Said’s Orientalism was published in 1978, a couple years before Jimmy Carter announced the “Carter Doctrine” in his January 1980 State of the Union address, that stated that the US would “use military force if necessary to defend its national interests in the Persian Gulf.” How much did that kind of Orientalism that was created during the British empire inform the Carter Doctrine, and to what extent has the Carter Doctrine stayed in force to this day?

OK: That’s a great question. There were triggers to the Carter Doctrine. One is the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Of course, Afghanistan is not in the Persian Gulf. What’s really going on there is it’s about the Iranian Revolution. The loss of this major pillar in the region—Iran, during the 1970s, had been fully embraced by the US to become a regional hegemon. Your listeners may or may not know this, or may not remember: US power was seen as in decline after the Vietnam War. The US had pulled back, beginning with president Nixon, from its regional policeman role and was looking for regional allies, and the Shah of Iran became one of them. Driven by higher oil prices, the Shah began buying everything the US wants to sell, and some of that, of course, is over the objections of the State Department and Defense Department, but gets the green light from president Nixon and his national security adviser Henry Kissinger.

The connection back to Orientalism is how Iran becomes viewed after this switch from a Cold War friend to a Cold War enemy. Of course the orientalist discussions of that become even more heightened after the Iran hostage crisis. And we can see this again, reflected most recently in the travel ban. How is Iran being listed in the travel ban? Why would it be listed in the travel ban? Iran and its allies are, in a fascinating way, actually in a tacit alliance with the United States against ISIS. So it’s remarkable that somehow Iran is getting listed in the travel ban.

Anyway, we then see how the Persian Gulf became depicted by the Carter Administration: it becomes known as the “Arc of Crisis.” Sam Huntington (later of Clash of Civilizations fame) wrote this policy paper, adopted by the Carter Administration, that says there is an “arc of crisis stretching from the Persian Gulf to the Indian Ocean.” Really what this is about is a crisis of American self-confidence. Where do we sit? Are we being pressured by the Soviet Union? How do we respond?

But to get back to your other point, which was about how the Carter Doctrine influences US foreign policy today: this is where we see the reemergence of the United States as a military power. Carter is going to call for an increase in the defense budget. He’s going to call for the stationing of troops in the Persian Gulf to protect the Persian Gulf. President Reagan, obviously, is going to dramatically expand on that in the Persian Gulf, and we’ll start to see the increasing number of US bases from the 1980s to today—not only in the number of bases in the Persian Gulf, but also their size. This began with the Carter Doctrine and it expanded under Reagan and of course everybody since.

CM: How vulnerable is the US to orientalism? That is, is the US easy prey when it comes to others exploiting our orientalism and potentially racist views of people from the Middle East? Does that kind of framing that we have of the Middle East exploitable by those who would wish to somehow do harm to the United States?

OK: I think the biggest issue is that we do harm to ourselves. It is important to remember, of course, that America’s “Orient” was not this area we call the Middle East. America’s “Orient,” the place it had the closer connections throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, was Japan and China. This is well documented by a number of fantastic scholars. We can also see the role of that orientalism on American policies, whether it’s the Chinese Exclusion Act or Japanese internment. We see the influence of that orientalism on America’s perception of the Other, in this case Asian-Americans from China or Japan. And then, of course, we did remarkable harm to Japanese-Americans with the Japanese internment. But that idea has been taken up, since 9/11, by the most extreme Islamophobic elements in the United States, and it’s viewed as a positive.

This great shame on the United States, the Japanese internment—and the terrible Supreme Court decision that endorsed it—is somehow now viewed as a positive, that this is something to be emulated after 9/11! The way that these extreme Islamophobic elements talk about it is that there were no other attacks, so the Japanese internment worked. Ignoring, of course, that these were well-entrenched communities, natural-born US citizens, who had to sell businesses at a dramatic loss, had to sell their homes at a loss, and many of them went into military service and fought for the United States, often valiantly, while their families were being interned. Yet all of that has been swept away and what we have are these extreme Islamophobic elements (some of whom, of course, are now linked to the Breitbart clique in the White House) saying, “No, we need to think about internment again if the need arises.”

So I think it’s less about orientalism creating this threat to us—we actually hurt ourselves, and we hurt American society when we continue to allow these kinds of racist sentiments and the basest most xenophobic elements in society to be empowered.

CM: Many critics say that often you’ll find anti-Israeli sentiments in university area studies. You’ll find sentiments that are anti-American. You’ll find sentiments that are against the national interests of the United States. How fair is it to label area studies at universities as anti-Semitic and anti-American?

OK: It’s completely unfair. For one thing, area studies are not hegemonic, and they’re not monolithic. Also, who defines the national interest? This is why Middle East studies are viewed as unique; Russia studies or Soviet studies or East Asia studies are viewed as directly linked to national interest, but Middle East studies were viewed as “complicated.” They are viewed as havens of anti-Americanism and anti-Israeli sentiment. Well, let’s actually look at it. Middle East studies are really no different in their origin, in some ways, from Russia studies or East Asia studies.

This idea that they are filled with anti-American or anti-Israeli sentiment is really a constructed notion by those with their own political and ideological agenda, and it’s that political and ideological agenda which is often tied to the state or to very narrow beliefs. We saw this with the rise of the neoconservatives in the George W. Bush Administration. One of the first things they did (led by the wife of vice president Dick Cheney, Lynn Cheney, and an organization she founded) was attack academia. They released this terrible report called “Defending Civilization,” this amazing title. What it really was, was a blacklist. It cited all of these comments, deliberately stripped of context, with which they targeted a number of academics they claimed were insufficiently patriotic after 9/11.

This was then followed up by a slew of other reports, often by very conservative or neoconservative thinktanks, which try to do the same thing. What they tried to claim was that who was really to blame for 9/11 was academia. Who was to blame? Edward Said and the influence of Orientalism. The failure was not decades of US policy; the failure was not the failure of the intelligence community to sufficiently track individuals here in this country, who they knew about; the failure was not on the George W. Bush Administration and the fact that the president had been briefed throughout the summer that Al Qaeda was planning to attack the United States on its soil; the failure was not the national security adviser, Condoleezza Rice, who ignored all these things. The failure was in academia because they did not see this coming. Well, apparently neither did the US government.

What we’re seeing with that kind of argument is a very narrow attempt at blaming, and what’s behind it is a political and ideological agenda that views academic knowledge with suspicion. It really taps into this preexisting anti-intellectual trend in the US that dates back to the nineteenth century if not before, that’s been well-documented by Richard Hofstadter and others.

And the Trump Administration has embraced this. Look at the comments by the current secretary of education at CPAC the other day: she said something to the effect that college professors indoctrinate their students, or tell their students what to think. I chuckled. Many of my colleagues chuckled. You could go on Twitter and see all kinds of comments about how we can’t even get students to read a syllabus, much less tell them what to think. But it taps into this idea—and there’s a vibrant base for it that wants to believe that these effete intellectuals, these urban intellectuals, these educated people know nothing and are weakening America. And what makes America strong? America is strong when we talk tough and act tough. What we need to do instead of looking at the university as something that weakens America—universities are our strength. They have always been our strength.

It’s one of the key pieces of the travel ban that the Trump administration tried to impose: our universities are considered the greatest in the world, and they attract people from abroad to come study here. They want to work with the best professors and in the best labs and have access to the best and brightest individuals. When we tell the world that we are going to start blocking out people by their religion or by their country of origin—when we start doing that in the 21st century, this is what actually weakens America. Canada and England and Germany all have excellent universities. People will be very happy to go there instead if their think they’re going to be safe and if they think they’re wanted.

This is what weakens America. It’s not about a debate of ideas. That’s what we’re talking about in the university; we’re having a debate of ideas. But what these counterforces want is a hegemonic discourse in which they impose what the national interest is and what national security is, and we either get on board or get out. Well, guess what? We’re not going anywhere.

CM: Osamah, I really appreciate you being on our show this week. Thank you so much, it really was a pleasure.

OK: Thanks so much, Chuck.