Transcribed from the 15 April 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

The reason for there not being a left, at least when it comes to black organizing, is that everybody got killed.

Chuck Mertz: Liberalism has failed black America. Negotiating with bigots is not something to be tolerated. There has to be something else; there has to be something more. Here to help us understand why liberalism has failed and what can be done to succeed in the fight for equality: Here in studio with us is Zoé Samudzi, a black feminist writer and PhD student in medical sociology at the University of California, San Francisco. Her current research is focused on critical race theory and biomedicalization.

Zoé Samudzi: Hi, good morning.

CM: Nice to meet you!

Zoé wrote a piece with William C. Anderson that was posted at ROAR Magazine‘s website called The Anarchism of Blackness: “The Democratic Party has led black America down a dead end. The sooner we begin to understand that, the more realistically we will be able to organize against fascism.”

Do we have William on the line as well? William, how are you?

William C. Anderson: Hey, I’m good. How about you?

CM: Good!

William C. Anderson is a freelance writer; his work has been published by The Guardian, MTV, Pitchfork, among others. Many of his writings can be found at Truthout or at the Praxis Center of Kalamazoo College, where he is a contributing editor covering race, class, and immigration.

Zoé, let’s start with you, since you are here in studio.

In your article, you write, “Liberalism and party politics have failed black America.” How has liberalism failed black America?

ZS: In the most recent election, it’s really clear that the electoral strategy for the Democratic Party was simply not being as bad as Republicans. In that way, they can continue to count on the black vote, but they don’t have to actually deliver anything for black people. And we saw that black people overwhelmingly voted for Hillary Clinton, and yet in this new moment of partisan resistance to Donald Trump and the Republican Party, Democrats haven’t really been doing anything to return the favor to their incredibly loyal constituent base in the black community.

CM: William, why do you think that the Democratic Party and liberalism have failed black America? As Zoé was just saying, it looks like they’ve been taking black America for granted.

WA: When we really look at the party politics of the Democratic Party, what they are doing is taking organizable folks, people who have passion, people who have drive, who have a desire to make change in this country—a lot of their constituents are good people, obviously, who do want to do the right thing and do have good values—and funneling them into this vortex. They absorb organizable people from the non-profit industrial complex, from NGOs and unions and burgeoning movements, and co-opt them, putting them into this hamster wheel where nothing is actually being accomplished.

It just all ends up being symbolic. So many people in the Democratic Party are tied to the same corporations and tied to the same violent structures that disenfranchise and oppress people. They’re just funneling people into the same structures that they purport to be against.

CM: Zoé, do you think that there’s an attempt by the party to “empower” black Americans but at the same time—because the system has so many shortcomings—it just leads to a sense of futility or even disenfranchisement despite this attempt at empowerment?

ZS: The Democratic Party praises the efforts of John Lewis, for example, and these old school pioneers of the civil rights movement; implicit to that praise of the civil rights movement is that the most important gains for black America have come through legislative reforms, through working with the system, through this idea of reconciliation, of cooperation, of reaching across party lines and accomplishing something together.

But there is a problem with legislative gains being made within a political system that doesn’t change fundamentally. Who are the arbiters of interpreting the legislation in favor of the black community? Who are the people giving black people rights and interpreting these laws equitably? When there are partisan turnovers of judgeships, and partisan turnovers of legislators, we see how quickly the gains that are made through legislative reform can be rolled back. We saw parts of the Voting Rights Act being gutted. We’re looking at gerrymandering and redistricting changing the outcome of elections.

And yet, because of a really intense fear of black radical organizing and black revolutionary activity, or of massive cataclysmic transformative changes, there is this really anti-black move, as William said, to co-opt this energy into something containable, something organizable. And they weaponize the civil rights movement and the language around peace and justice to do that.

CM: William, why isn’t being better than Republicans on race issues—why isn’t that low bar enough, anymore, for black Americans to support the Democratic Party?

WA: I don’t think it’s hyperbole to talk about a neofascist movement stemming from the Republican Party. The GOP is so bad that being better than them, being just a tiny little bit to the left of them, saying things that are largely symbolic about being better people and having better morals than the Republicans—it’s not good enough. We need an actual left in this country. There is no real functioning left opposition in this country.

And the Democratic Party is always, essentially, compromising. That is their definition of being the opposition. It’s compromising and saying, “Okay, we’re willing to work with you.” That is not how opposition works.

If we’re actually going to accomplish anything, there needs to be a real left in this country. That is extremely important, because if we’re following the Democrats, we’re going to end up going along with whatever the Republicans are doing every single time, and saying, “You want to do this? Then let us have this.” That’s not a movement. That’s not resistance. That’s complete compromise, and is completely pointless and a waste of people’s energy, because we’re always going to lose that way.

We are the people who are going to bring about our own liberation. It’s going to be people who are working class. It’s going to be the gangs. It’s going to be people on welfare. It’s going to be people who have to deal with the police every day. These are the folks who are going to bring about our liberation. It’s not going to come from one leader.

CM: Zoé, following up on William, why do you think there isn’t a left in the US? Are we still suffering from the Red Scare of the 1950s? What is the reason there seems to be—especially from the Democratic Party, the opposition party, supposedly—no real appetite for left-leaning policies?

ZS: White supremacy is bipartisan. Simply because you are slightly less bad than the Republican Party doesn’t mean that you actually have any desire for the actualization of black liberation. It doesn’t mean that you have any desire to see a power structure toppled and overturned.

The reason there is not a left, at least when it comes to black organizing, is that everybody got killed. The government did a really good job of making people informants, turning people against one another, and then straight up assassinating much of the leadership. With these assassinations and the rise of incredibly expansive surveillance techniques, and with the expansion of the prison-industrial complex and mass incarceration, I think—at least from a young black leftist point of view—there’s something incredibly scary about speaking truth to power.

Also, for white leftists there is an uncomfortable habit of walking into spaces of color and telling black people how to understand class and how to understand structures, and there’s a fragmenting because of white leftists’ own investment in white supremacy that is alienating to other people. There is left sectarianism and a difficulty for us to realize that although we have differential understandings of how a revolutionary state is formed, ultimately we share an enemy. So how do we funnel our commonalities into a space where our energies can be mobilized and we can act towards the same thing?

CM: William, Zoé was talking about the threat of violence and the violence that has been committed against black leadership in the past. Earlier she was talking about the inability of our electoral system to be a way towards the permanent reform that we need. How much do you think voters realize the fragility of reform? That once a group gets rights, that it is a constant fight for those rights into the future? That those rights are far from being set in stone, that they can be just torn up and thrown away overnight?

WA: I think it varies depending on where you are. I’m talking to you from Birmingham, Alabama right now. And I grew up in Shelby County, where the Voting Rights Act was infamously targeted. That situation in 2013, Shelby County v. Holder, was a prime example of the fact that all of the gains that we make within this current system can easily be taken away.

When we have a party like the Democratic Party, again, that is compromising constantly, it is really a dead-end. Some sort of independent political power needs to be organized, and it has to move away from these structures that have anti-black violence embedded in them. These structures have really terrible histories relating to genocide and enslavement. The Electoral College obviously has a deep history embedded in it, the fact that it was structured around enslavement and the Three-Fifths Compromise.

So when you tell black people to get out and vote Democrat, it completely undermines the fact that our deaths and the brutality that’s been leveled against us for centuries is a part of the very things that you are telling us are going to bring us liberation. It’s counterproductive to think that we’re going to be freed by the very things that have brutality against us built into them. It’s kind of absurd, really.

CM: Zoé, what will happen when and if the Democratic Party compromises with the bigotry and the hate that is being increasingly normalized by the Trump Administration? What will take place if that kind of compromise happens?

ZS: We’re fucked. I mean, honestly we are. I remember when the GOP office in North Carolina got burned down, and the response of progressives was to raise thirteen thousand dollars for that office, when in North Carolina trans rights are under brutal attack, and all of that money could have been mobilized for a community that’s being directly harmed by that state institution.

The Democratic obsession with moral sanctimony and being able to claim that “we’re better than them, we’re more virtuous and more righteous than them, and that’s why we try to compromise,” is really going to be the demise of many marginalized communities. That morality always completely fails to translate into any kind of material support or safety or security or protection or benefit.

Every single Trump nominee has been confirmed. Now we have people in power who are going to be chipping away at not only rights-based gains but also communities and institutions for protection, and if the Democrats don’t realize that just being nominally better than Republicans doesn’t actually mean anything, I’m really worried about what’s going to happen in the coming four years.

CM: William, people have been really critical of the Democratic Party and whatever constitutes the left, critical of what they see as a lack of political imagination on the left that they don’t seem to be seeing on the right. They believe that there is more political imagination on the right.

Do you believe that there is more political imagination on the right than on the left?

Neo-Nazis do not just have a politics. They do not just have an ideology and a set of things that they think about “lesser” peoples. There is a material goal that they are moving towards: the fragmenting of communities and the extermination of peoples in order to ensure the safety of whiteness. Liberalism, on the other hand, is apolitical. There is no structural, institutional, material end goal.

WA: I do agree that there is more political imagination on the right, and I think that they are better organized. I think the Tea Party was a prime example of that. Zoé said something that was really important about people being scared to be leftist because of people in the movement being killed, and the horrible violence that the black liberation movement and other movements have seen. That is really what we are talking about when it comes to the necessity of blackness and the anarchistic nature of it. If we’re going to go forward, there needs to be a lot of alternatives as far as organizing, because movements in the past have been targeted in ways where leadership has been assassinated and suppressed.

We are the people who are going to bring about our own liberation. It’s going to be people who are working class. It’s going to be the gangs. It’s going to be people on welfare. It’s going to be people who have to deal with the police every day. These are the folks who are going to bring about our liberation. It’s not going to come from one leader.

People have really bought into this idea that Martin Luther King and nonviolence are the only ways to achieve liberation, and that’s something that the Democratic Party has fostered a lot. It’s extremely problematic because it erases history; it erases large parts of not only King’s legacy but other parts of the civil rights movement. They don’t talk about the fact that when the Children’s March was happening in Birmingham and people were getting sprayed by hoses and having dogs sicced on them, that there were also black folks out there with bottles and rocks and knives, and they were fighting back. They don’t talk about that when you watch documentaries. They don’t talk about that in the neoliberal retelling of history. There were people out there who were actually actively defending themselves. Young people, older folks as well. You don’t hear about those sorts of things.

There needs to be a real education around the fact that we have to build something that is actually sustainable and that is not imaginary, and that isn’t romanticized. That’s going to have to happen through real organizing and real movements of the left. This is something that the right has been very good at, because they are absolutely intolerant of anything that they consider too watered down or too easygoing. That needs to happen on the left as well. We need to become firm about what our values are and what we’re not going to stand for and what we’re not going to accept from people in the Democratic Party, from politicians who are trying to appeal to us. We need to set the standard, and there needs to be a line drawn. There doesn’t need to be any kind of playing around. It needs to be set there. It needs to be really, really firm.

ZS: If I could just a make a point to the idea of Republicans being more imaginative: when it comes to neo-Nazis, and when it comes to “having dialogue” with neo-Nazis (which I absolutely don’t agree with in the slightest), neo-Nazis do not just have a politic. They do not just have an ideology and a set of things that they think about “lesser” peoples. There is a material goal that they are moving towards. If they are emulating Nazism, this goal is the fragmenting of communities and the extermination of peoples in order to ensure the safety of whiteness.

That is very much the ethos of the Republican Party. Perhaps they are not working towards a system that mirrors Nazi Germany (well, I hope not), but they have a goal, and the goal is the preservation of whiteness, a preservation of the interests of the capitalist class, and a preservation of the capitalist system.

And liberalism, in my opinion, is apolitical. There is no structural, institutional, material end goal. There are values that they claim to espouse, but those values do not themselves amount to a system. And there’s a lack of political imagination on the left because we haven’t seen a system that functions the way we want. There are examples that people can be working towards on the left, but in the Democratic Party, there is not that system to emulate and move towards. There is simply a reaction to the Republican Party.

When you’re constantly reacting to something, you are not putting your energy into generating something, into imagining something. The energy for imagination and the energy for thinking about what the world we want to live in looks like is being siphoned into trying to work with this horribly racist, genocidal, fascistic group of people instead of working with the base that’s been loyal to them and asking what our communities need. What would be a better way of keeping communities safe that doesn’t necessarily force you to call the police? What does it mean to have a system of entitlements—not just rights—to food and housing and education?

They don’t want to do that, because they don’t want that system to come into existence, as much as they claim to.

CM: Zoé, just a real quick follow-up, because I’ve been thinking about this, too: what does the Democratic Party stand for? I think the people who are attracted to the Clintonian wing of the Democratic party want to be centrist. They don’t want to be rightwing; they don’t want to be leftwing. They want to be bipartisan; as William was saying, they want to be seen as compromisers.

Is being a centrist political party a sustainable or winning strategy in politics?

ZS: No! It’s like being “neutral.” It’s like when someone says, “Well, I’m Switzerland to this,” but they don’t realize that Switzerland allowed the Nazis to use their banks and keep the money that they stole from people in their country. That’s how I feel about the Democratic Party. They want to come off as being “here to negotiate, to construct a better world for all.” But when you’re fighting against a group of people that is actively attempting to strip people of their rights, what does it mean to meet those people halfway? What do you lose in the integrity of your politics when you think that negotiating with terrorists is a viable political strategy?

People are deeply invested in the constitution without understanding the way that the constitution has been weaponized against folks. They’re very scared of admitting what America represents, because even in the liberal imaginary, it’s about equality and opportunity. But what does opportunity mean when you are never given the resources or the ability to move beyond a particular classed or racialized condition?

CM: William, how much is this not just about Trump but about the Republican Party in general?

I think far too often people focus on Trump instead of the overall policies of the Republican Party, and far too often I’m hearing people saying that this was a complete shock, that nobody saw this rise of bigotry and hatred coming, and that it came completely out of the blue.

WA: That is absolutely ridiculous to me, hearing people talk about the shock of this situation. Because this country was founded on everything that it’s doing right now. It was founded on racism, it was founded on xenophobia, it was founded on genocide and enslavement.

This country is in a predicament now where people are realizing that we have to deal with white supremacy, and we have to deal with the ideology of whiteness. Everything that’s happening is based around this sickness. This country has a sickness. The ideology of white supremacy and whiteness is that sickness. Until we actually deal with the fact that we have a society built around white supremacy, we’re not going to see any real changes.

Trump is a symptom of that. He’s a symptom of white America trying to maintain itself, of institutional white supremacy trying to preserve itself. In this country, the refugee crisis, the rising rhetoric around immigration, the xenophobia—and really, too, the presidency of Barack Obama, as symbolic as it was—these things really put fear into the white Western world. It’s very apparent that white America is struggling with the idea of losing power even though it hasn’t actually been losing power.

Trump is that. Marine Le Pen in France, she is that. The growing right movement throughout Europe—all of this is a response to that. White folks are organizing themselves throughout the West to preserve white supremacy and to preserve whiteness. We’re being doubled down on in a way that’s really ridiculous, because there isn’t anything truly threatening white supremacy to the extent that a Trump would be necessary.

Trump is really not smart. He’s not a president who is functional in any way. He’s really just a bad incarnation of those resentments that I’m talking about. So the fact that you’re willing to sink to that level, to put somebody like Donald Trump in the presidency, just shows how sick white supremacy is. This is someone who is going to hurt everybody, including the folks who voted for him. So we have to deal with that sickness.

CM: William, you write, “Blackness is, in so many ways, anarchistic. African-Americans, as an ethno-social identity comprised of descendants from enslaved Africans, have innovated new cultures and social organizations much like anarchism would require us to do: outside of state structures.”

What are some of those anarchistic black structures that, being white, I am certain I’m not aware of?

WA: Black existence in this country is largely framed by our existence in the afterlife of slavery, and being seen perpetually as slaves. Obviously, blackness is much more dynamic than that, and much more complex than that. But this society has framed blackness in such a way that we have always existed in this way that is very unique and has a lot of potential to be threatening to the state.

The nature of black existence is filled with many things that can be utilized to resist and to build an active liberation movement that actually makes real accomplishments. It’s all throughout history: numerous uprisings against slavery, the black movement going into reconstruction, all the way to fighting Jim Crow. Black people have a beautiful history of resistance in this country.

A lot of that is based around the fact that we are are not seen as truly being citizens in this country. Even though I’m descended from enslaved Africans, even though I’m descended from people who have been in this country for so long, I can still get told, “Go back to Africa,” as if my people were not brought here a very long time ago. Existing outside of citizenship, existing outside of Americanness, is one of those underlying factors I’m talking about with the anarchism of blackness.

It’s amazing to think about how that can be utilized for the struggle, because everything that we are talking about needing to accomplish can happen inside that anarchism, that spontaneous nature that black people have always had to have in order to survive, to fight against structures that were always trying to confine or kill us, or brutalize us at every turn. It’s really inherent in our survival.

Essentially what I’m saying is that everything we need is already inside of us as black people. We can look at other people of color in this country, too, and there are movements and histories there as well that folks can build off of. It’s absolutely necessary that we recognize our very rich history of rebellion in this country, one that we can learn from and build off of, and that we can use right now in this moment.

CM: Zoé, how much do you think issues of race are avoided out of discomfort over how much they may reveal the shortcomings of what the US is, compared to what we believe it is supposed to be? Do we not address racial inequality because it reveals that, yes, there is inequality in the nation of “We the People”? Is race, for Americans, kind of embarrassing?

ZS: Absolutely. Robin DiAngelo wrote an academic article about white fragility, about how even good white folks are much more offended by being called racist than they are by the centuries of racism and white supremacy and settler-colonialism that are inherent to the United States. I think it’s really interesting the ways in which white allyship gets weaponized when black folks start sharing these inconvenient truths.

Even people who are supposed to be progressives take great pains to defend the constitution. People say it’s unconstitutional that Donald Trump would do this or that—absolutely, yes, it is unconstitutional. But also, the founding document of the United States, the declaration of independence, where Thomas Jefferson wrote “all men are created equal,” was written by a man who literally owned other people.

The things that Trump is going to do during his term are going to position large swathes of white America in a place where they are going to feel a boot on their necks that they were not anticipating.

When we pay this homage to the founding fathers and we thank them profusely for their efforts, we have to understand that the American revolution was fought to codify citizenship for property owners and to centralize privatization and property rights—as opposed to equality and all of these other “liberal Enlightenment values”—in the foundation of this country.

People are deeply invested in the constitution without understanding the way that the constitution has been weaponized against folks and the ways in which, again, positive legislation can change at the drop of a hat. They’re very scared of admitting what America represents, because even in the liberal imaginary, it’s about equality, it’s about opportunity. But what does opportunity mean when you are never given the resources or the ability to move beyond a particular classed or racialized condition?

CM: William, you and Zoé write, “The state can only function through abuse, so we can only prevail through organizing grounded in radical love and solidarity.” I’ll ask Zoé what you mean by radical love. But why do you think that the state can only function through abuse?

WA: Going off of what Zoé just said (it was a perfect segue into this): when we hear these conversations about Trump, so many liberals constantly make Hitler comparisons, when Hitler was inspired by the genocidal nature of the United States and the formation of the state here. The founding fathers—slaveowners, genocidal murderers, and nonetheless held in high regard and given accolades—are a great comparison for Trump as well.

This man has Andrew Jackson as a figure who he looks to as a perfect example. Make that comparison. Make a comparison of Trump to the people who are really the foundation of everything that we’re dealing with now. The US state is positioned such in a way that we have to start being honest about what it represents, what it is, and how it treats us. The founding fathers and the constitution—those things are lofty ideals on paper that didn’t apply to everyone. It’s simple and plain: these are structures of violence, and they have hovered over our heads and our existence in this country since we’ve been here. It’s not sustainable to have movements that cherrypick these symbolic things from those structures and buy into ideas that are just not real.

Looking at the GOP now: we’re dealing with people who are not concerned about being racist, who are not concerned about being genocidal, who are not concerned about dropping bombs and destroying people’s lives, destabilizing their countries, murdering people’s families. When we’re dealing with a party like that, why in the world would you waste your time trying to defeat them through some sort of moralism? Their actions tell you that they’re not concerned about killing, about being terrible in general. It’s obvious through their actions that they’re not concerned about that.

We have to look at the state for what it is. We have to move away from buying into the idea that the founding fathers and the genocide and enslavement that founded this country were things that had to happen and we should just forget about them or look at them in a positive way, because, hey, it created this great country that we all get to be a part of. That’s a farce.

CM: So Zoé, what do you and William mean by “radical love”?

ZS: I think we agree on it for the most part, but for me personally: when I talk about radical love, I think about generating new worlds for us all to inhabit. That, for me, is fundamentally a spiritual activity. It forces us to completely reorient ourselves in the way that we interact with and understand other people. In order to really see and love one another we have to understand what personhood and humanity mean outside of the way that we’re commodified within racial capitalism. Radical love is to see a person for what they are really worth, not just for the value and the capital that they can accrue for this economic system, but for what they are worth and what they are intrinsically entitled to as people—the fact that they are entitled to housing, to safety, to a freedom from violence.

To radically love is to believe that every single person deserves this, and we will fight to ensure that people can live safer, healthier lives, and we can imagine a world that doesn’t just allow this but where these entitlements are built in.

CM: With all of our guests, we end interviews with the Question from Hell: the question we hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate your response.

I’ll start with you, William. Blacks are far more aware of state violence than whites, I think I can pretty safely say. Do you think, under Trump, whites will soon have a better understanding of that state violence?

WA: I don’t think that white folks are in a position to understand state violence the way that black people understand it, and I don’t think they are going to any time soon. But I do think that the things that Trump is going to do during his term are going to position large swathes of white America in a place where, yes, they are going to feel a boot on their necks that they were not anticipating.

It’s unfortunate that so many folks across white America have been duped into believing in whiteness as it stands, because since the civil war and even before that, so many white people who have more in common with me as, far as class goes, than they do with Donald Trump have thought that they are better than me because they have white skin. That is truly a tragedy, because it would be beneficial for folks to understand that it would make sense for us to work together to achieve the equality and the security that we all desire for our families and for our communities.

That’s why whiteness is the problem. Because these folks, to a large extent, are being tricked. It’s something that has been happening for such a long time that I don’t know if Donald Trump is going to open eyes. Regardless, I’m going to be trying to survive and live, and I’m going to do what’s necessary for my survival and my family’s survival. Whether they open their eyes or not is really on white America, and white America has to deal with that problem. I’m not going to concern myself with it; I’m going to do what I need to be doing.

CM: Zoé, our Question from Hell for you is: Can we vote white supremacy out of office?

ZS: We can’t. Democracy wasn’t created to not have white supremacy. This political system was based upon the fetish for property rights, for accumulation of capital, for hoarding, and for the inequitable distribution of capital. The system was created to be inequitable. Built into every single institution that props up the system is inequity. Can we use an inequitable system to vote inequity out of the system? No.

There are strategic uses of the system. Fundamental to my politics is the idea of harm reduction. If we can get people to construct policies to mitigate harm as much as possible, that is what I see the system serving, ultimately: potential for enabling programs and policies to get people access to resources to survive. But survival is not the goal. It is to thrive, it is to flourish, it is to exist in a country where people do not have to walk down the street wondering if the cops are going to roll up on them or not.

Can we use a “democratic” system grounded in the removal and genocide of indigenous people and the enslavement of other people—a system that revolves in so many ways around anti-blackness—to alleviate any of those problems? No, we cannot.

CM: That’s Zoé Samudzi; on the line with us is William C. Anderson live from Birmingham. It gives me great joy to hear people speaking truth. It’s very rare that you actually hear people being so honest, especially on issues of race. Thank you both so much for being on our show today.

ZS: Thank you.

WA: Thanks for having us.

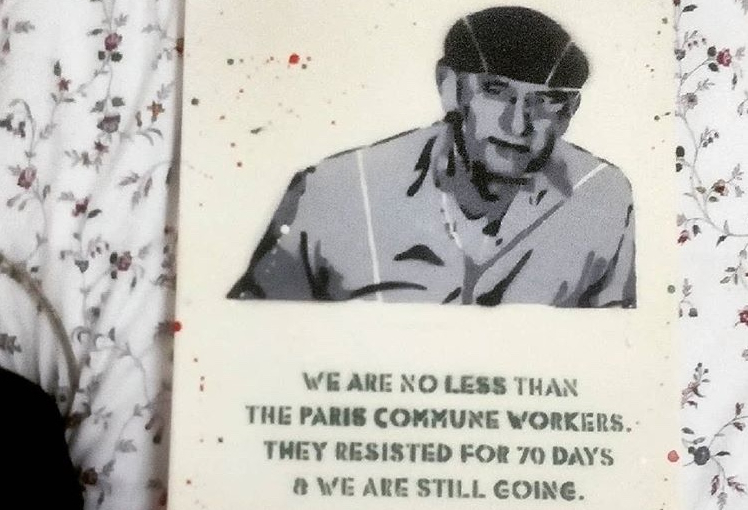

Featured image source: East Bay Indymedia