Transcribed from the 29 July 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

We can’t dig our way out of the Trump era and the really dangerous times we’re in unless we go back to workers being able to challenge capital at the point of production.

Chuck Mertz: It used to be that US workers scored victory after victory in their fight for labor rights. And those victories weren’t only for union members, but all US workers benefited from unions’ achievements. So what the hell happened?

Here to explain what happened and how we can get back to challenging power with power, Jane F. McAlevey is author of No Shortcuts: Organizing for Power in the New Gilded Age. Welcome to This is Hell!, Jane.

Jane McAlevey: It’s a delight to be here, thank you.

CM: You write, “There’s an informal gestalt in much of academia that unions are not social movements at all, that unions equate to undemocratic top-down bureaucracy. Likewise, scholars assume that material gain is the primary concern of unions, missing that workplace fights are most importantly about one of the deepest of human emotional needs: dignity. The day-in day-out degradation of people’s self worth is what can drive workers to form the solidarity needed to face today’s union busters.”

Unions are greedy, and its leadership is corrupt; that’s the way I heard it when I was growing up. And I’m betting that’s the way it is today. But apparently it’s not. This is from a 30 January 2017 Pew poll press release: “About six in ten adults today have a favorable view of labor unions and business corporations, according to a Pew research center survey. Views of both have grown more positive since March 2015, when roughly half of adults expressed a favorable view of each.”

Is there, then, a disconnect between the way the public views unions and the way they are presented in academia? Does the public view unions more favorably than academia does?

JM: I think so. There are several things. I’ll just start by saying I’m pretty down on pollsters, and I have been for some time. So whether it’s Pew or any number of the consultant industrial complex players who have been obsessing for the last 25 years about frame and narrative (that’s the way you get out of this mess?), we should be discounting a lot of what the pollsters tell us on a regular basis. That’s been clear if you watched how they covered Pennsylvania, where they said Clinton was seventeen points ahead and she lost, or the Brexit vote in England, or—fill in the blank.

Finally, reality is coming home to roost for the pollster industry. When someone rings you up and you’re at the dinner table, and they ask your opinion about something and then they hang up the phone five minutes later, that’s not a really good measure of actually how people feel about what’s happening in this country.

Most data over time argues that if most Americans could have a union without the terror campaign that they are subjected to when they try to simply form a union, we’d have about eighty percent union membership in this country right now. I’m really not exaggerating.

What people don’t understand, unless they’ve gone through it, is what workers are put through in these vicious, anti-democratic terror campaigns. I talk about one of them in No Shortcuts, in the chapter on Smithfield Foods, which chronicles an amazing victory by five thousand workers in the largest pork production facility in the world (which the Chinese now own, by the way), which sits in the Third World country called North Carolina. The stories of what those workers were put through by their employer between the late 1990s and early 2008, when they finally actually voted to form a union against all odds—it’s when people realize how treacherous those campaigns are that you realize why we’re at six percent union density. It’s not a reflection of how many American workers want a union or feel like they need a union.

CM: Why does academia separate unions from social movements? Is this about separating economics from activism? This reminds me of last week’s conversation I had with economist Samuel Bowles about economic incentives versus ethical incentives, and how economic incentives bring suspicion and ethical incentives increase participation. How much more do we distrust labor organizing than other types of activism because it is seen as being about economics and not about ethics?

JM: Academics (including economists) usually look at it and view union membership percentages in the context of a desire for material gain, and that’s just not my experience after 25 years of organizing—25 years of actually working with America’s workers all over the US.

We’re not winning tough campaigns like the campaign at Smithfield Foods in North Carolina in 2008 because the workers want a dollar-an-hour raise, or even fifteen dollars an hour, to be honest. We’re winning them because the boss has so offended the dignity of the workers, wherever the workplace is, whether it’s the Chicago schools or the Smithfield Foods factory in the South. Workers have been so under assault in their day-to-day jobs by the pressures of neoliberalism and the hyper market capitalism which we’re living under right now—the tough campaigns are not about material gain. They’re about dignity.

That’s why I try to say to the academic world: you’re missing the most important part of why workers can sustain really hard campaigns. It’s the indignities against the human spirit under hyper-greedy, vicious capitalism—market-driven capitalism, unfettered capitalism and greed, which is what’s driving the country right now—that lead people to stand up for themselves. Not, “Hey, I want to win a dollar.”

CM: How much of the reason we separate labor organizing from other social movements is because we have a blind spot when it comes to the way economics touches everything? How much is this because of a refusal—either conscious or not—the public has in being critical of our economic system, of capitalism? Do we separate union organizing from other social movements because we are unwilling to see the links to capitalism?

JM: I think so. I also think we’re really uncomfortable with power. And the labor movement is the place, in the last hundred years or so in this country, where the most power has actually been exercised. One of the biggest problems is that within the elite media establishment in the US, most people are middle class or upper middle class. They’ve never themselves actually come from a union. They’ve heard stories about it from their mom or dad or someone else—meaning someone from the employer class. They experience it as something that gets in their way. They don’t experience it as something that’s fundamental and liberating.

Trade union-hired pollsters in the late 1990s and early 2000s told us that we should never say the words ‘working class,’ because that brought up bad images. Everyone wants to be middle class, so we should only talk about the middle class. And even saying the words middle class became unfashionable to the pollsters by the early 2000s; instead, any time we were in a public place we had to say ‘working families.’

Even among so-called liberal/left media sources, you can see a real distinction between identity politics, climate change, all of that, and then the labor movement, which is either written off as dead or written off as only purely top-down and corrupt. But we’re in such a crisis in this country right now. I’ve been imploring people in the movement to understand that we can’t dig our way out of the Trump era and the really dangerous times we’re in unless we go back to workers being able to challenge capital at the point of production, which means in the workplace.

The Koch brothers and the super-wealthy have already essentially bought the political system. They did that through a series of three different supreme court cases, two of which happened since 2010. They got their people in, they appointed their supreme court justices. There was a pivotal meeting in 1973 where a young Dick Cheney and a young Karl Rove and a bunch of these characters (who are still dominant in the vicious spirit of this country right now) were off plotting in Cheyenne, Wyoming, at a ranch. They were making a plan in 1973 for how to roll back every gain that the labor movement, the women’s movement, and the civil rights movement just made. That’s ’73. They had a long view about strategy, and they understand power. They said in this meeting, in 1973, that they thought it would take 25 to 30 years to roll back all the gains made by the progressive movements—the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, Social Security, Medicaid, the Voting Rights Act, the Civil Rights Act, trade union law, all of it—and they’ve been doing it.

Part of the critique I have of our side, of the movement, is that we think in nanoseconds. Like, what protest can we go to tomorrow? It’s not the long view that Dick Cheney had, which was: How do we systematically take control of 31 states? We can have a constitutional convention in the US; it might take us 25 years to get there, just in time for the demographic changes that say white people will be in the minority, so we’ll have just enough time to change the constitution of the US so that you have to have been born here for three generations to vote. That’s the long view of really crazy rightwing people with a lot of corporate money behind them, and they’ve been spinning the narrative against unions for a long time.

So to come back to the original question: one, our movement needs a long view; and two, people need to really rethink their understanding of the value of trade unions in the United States. Are a handful of them corrupt? Top-down? Messy? Sure. I write about it in both of my books. Despite the fact that I’ve been involved in some things in the labor movement which just made me gasp and cry and scream and fight, I’ve mostly been involved in union campaigns where workers by the thousands if not tens of thousands—in contemporary times—were standing up and changing their lives. And if people think that we can take on Trump just in the political arena, just in the civic arena, just by going to the voting booths, and not by striking and messing with capital at the point of production, I think that’s a misread of history.

CM: You write, “In the United States, C. Wright Mills popularized the concept of power and power structures in his book The Power Elite, published in 1956. In the sixty years since then, progressives have largely ignored and omitted discussions about power or power structures. Nothing produces deer-in-the-headlights moments for activists in the United States like the question, ‘What’s your theory of power?’”

To you, what explains why we look like deer in headlights when we’re asked what our theory of power is? What does that say about the US worldview? We had a listener who has traveled all over the world. He was a listener in Portland, Oregon, who was on his way to Italy, and he drove here to Chicago first to hang out with us at the bar downstairs from our office, and he told me that of all the places he’s traveled in the world, he has never seen a lack of class consciousness like he’s seen here in the United States. Is that lack of class consciousness part of that deer-in-the-headlights look we give to people when they ask us what our theory of power is?

JM: Yes. Definitely. You know, I dropped out of high school, dropped out of undergraduate, dropped out of everything, and then I got this PhD late in life, which gave me time to read as opposed to just running campaigns in the field. They had to confer a degree on me in 2009, by some life experience and stuff, just to get in. But there I am in 2010 sitting in a university for the first time in decades, and one of the first books assigned to me, in sociology, is de Tocqueville’s Democracy in America, the 880-page tome which some people really obsess about—in fact, Newt Gingrich, Dick Cheney, all those guys obsess about the de Tocqueville book. That book, in the 1800s, spun the narrative that America is the land of the free, the home of the brave, that it’s a “post-class” society because we don’t have a formal aristocracy. He was coming from the formalized French aristocracy. I always look at the guy and think: what he was looking for is what the elites have gotten in this country. While we don’t have a formal aristocracy, we certainly have an informal aristocracy.

I was fascinated by that, because the book was written 170 years ago, and it spins a narrative that has been being spun to us in this country ever since. Now we’re told we’re in a “post-racial” society. We’re in the most racist moment since 1925 right now. It’s not post-racial! And we’re not post-class, and we never have been. We are so class-stratified. If you look at the statistics, we are an incredibly class-stratified society. We have numbers that look like dictatorships in other countries in terms of our class stratification. And yet the word class is not used.

Part of my criticism of some of the leadership of the trade union movement (that I’ve worked very closely with over the years) is of the consultant industrial complex. This is what I covered in my first book: I described a meeting where I was sitting in a national union headquarters, and pollsters were coming in and showing senior staff what the latest data says, and the way that we should learn to talk to American workers as trade unionists. And guess what they told us? They told us that we shouldn’t use the world class. They told us that we should never say the words working class, because that brought up bad images, and everyone wants to be middle class, so we should only talk about the middle class. This is trade union-hired pollsters in the late 1990s and early 2000s. And even saying the words middle class became unfashionable to the pollsters by the early 2000s, and instead any time we were in a public place we had to say working families.

Remember that the workers themselves have the answers to a lot of the questions. They’re really smart. They know a lot.

Working families. So if you wonder about how strong the narrative is that we shouldn’t discuss the word class, it’s even deeply embedded in the trade union movement. Leaders were listening to pollsters, who mostly worked for the Democratic Party, who were coming into our union headquarters in Washington DC to tell us that we shouldn’t talk about the working class, we should only talk about working families, because working families “polled better.” That was one of the days that I wanted to take an ice pick and stick it through my brain. I was like, are you people kidding me? Have you been out in this country actually talking to the working class? Because they know that they’re the working class.

It’s really, really deep how little we discuss class, and you can tie that right back to your friend who is on his way to Italy: if you don’t understand class, then you don’t understand class struggle, and therefore you don’t have a theory of power, in my view. I’m super clear. I have a theory of power. I’ve been using it for 25 years. It’s called class struggle.

CM: Let’s talk about the power structure for a second. How transparent is the power structure? Is it easy to analyze and quantify? How little do we understand that power structure?

JM: There are some people who understand it very well, but I think that most people don’t have any idea how the power structure works. I work with a method called power structure analysis. I don’t go into any serious campaign with anyone anywhere without first doing what’s called a power structure analysis, a social-structural power analysis of the region or the city that I’m in. The kind of power structure analysis I’m talking about is a way that we can understand the local elites, and their connection to the state and national elites. It is one that looks at not just a corporate board of directors. Most union researchers look at the corporate board of directors, the shareholders, the vendors, and the purchaser agreements. That’s the least interesting part of the work to me. The most interesting part is that in this country, we know that there’s still a lot of power at the state level.

What we have to do as movement activists and leaders and organizers is make the time to sit and seriously understand: who’s on the city council, who’s on the town council? More importantly, who’s on the zoning board? Who’s on the planning board? Last year I was helping to run a big campaign in Philadelphia—where thousands of workers won, by the way. I was hired to come in and help a campaign that was already in progress, and I had the pleasure of jumping on board and helping bring home the end of the fight; seven different hospitals, lots of different workers forming new unions, big first contract fights, strikes, etcetera. There I was, flown into Philadelphia, and I said to the leadership, look, personally I can’t figure out how we’re going to run a city-wide first contract struggle across a bunch of players and a bunch of for-profit and not-for-profit hospital corporations, where the workers are in a great fight against them, unless we run a parallel power analysis structure for like six weeks.

We brought in four people from Canada, because we were so balls-to-the-wall in the middle of a campaign; we just needed help. They were from different unions up there who I had been doing some training work with, and I said if you really want to learn, send your staff down here, we’re in a live fight, and we don’t really understand who’s moving power in the city or in greater Philadelphia. So we spent six weeks: we did 65 interviews with journalists, academics, policy makers, former staff people of congressional members and city councils and mayors and reporters. You go out and you ask the same set of questions to a whole bunch of different players in the region. At the same time, you’re digging into the internet, every time you hear a name for the fifth time.

And at the end of every interview, you say, “Who do you think gets into the mayor’s office with no phonecalls, they just walk in? Who do you think gets into the mayor’s office after five phonecalls? Who never gets into the mayor’s office?” There’s a whole series of methods that we’ve developed about how you can quickly understand who controls power in a social structural analysis in a given region. And guess who has the best answer to those questions? The secretaries. The security guards at the door. Not the damn high-falutin’ academics in the University of Pennsylvania.

I was talking to a nurse one day, we’re trying to chart relationships, and I’m like, “So what’s your husband do?” And she says, “Oh, my husband’s a security guard down at city hall. Well, he’s a cop but he does top-level security to the mayor’s office.” This is a real story. Classic. I just burst out laughing. I was like, “Are you kidding me? Can I have a conversation with him?” Because who knows who gets into the mayor’s office? The guards.

Ordinary people have tremendous knowledge. In the power structure analysis methods that I use and that I teach and that I was taught when I was younger—I haven’t invented nothing. I have great mentors, I have great teachers, and I hope to be teaching lots of rank-and-file member-leaders and staff the same stuff I was taught many years ago, which is: put your brains on. Go ask a lot of questions. Do some deep digging. And remember that the workers themselves have the answers to a lot of the questions. They’re really smart. They know a lot.

But people in our country just run around. Something goes wrong, they call up a protest. Now it’s like Facebook, lots of noise, activity, protest, bla bla. Stop! Take the time to think it through. Who’s actually holding power? Who can actually give you what you need in the campaign that you’re trying to win? How much power do you have to bring to bear to win the fight? There’s a whole series of questions that we just don’t ask as a movement, and it’s part of why we’re in the mess we’re in.

We have to build another underground railroad. Now. People are in deep trouble right now in this country. They’re just being grabbed at their job and picked up at school. So there is a ‘resist‘ that matters. But there is so much more that we have to do besides resist.

CM: How do you feel about this word that the Democratic Party is using to try to activate their base, which is resist? Is resist enough? Why does organizing do more than just resist?

JM: Resist is not enough. Although we understand it’s central—we have to defend a lot of people right now in this country. I was just at a meeting in New York City with some people who were from Texas and some of the border states. At one point it was like, “Wow, we have to build another underground railroad. Now.” People are in deep trouble right now in this country. They’re just being grabbed at their job and picked up at school. So there is a resist that matters. But there is so much more that we have to do besides resist.

And resist alone is not particularly motivating to a lot of people. When a worker makes a decision to stand up for themselves and to show up at the twenty meetings that they have to show up at to get the work done in the campaign, they’re not coming because someone says, “If you come to a meeting, we’re going to make it so things are less bad.” They’re coming because their expectation has been raised that they can actually make positive change in their life.

And the leadership of the Democratic Party is just in the way at this point. Chuck Schumer wrote an op-ed this week in the New York Times announcing that their plan is called “A Better Deal.” Like, we’re better? We’re the better people? Did you read that thing? I thought, this is their response to the Donald Trump moment we’re in? They went down to Virginia and they had a retreat and then their press messaging is, “Our side is better”? Are you kidding me?

The leadership is in our way, not just lacking creativity. They are part of the problem. Back at that ’73 Cheney-Rove meeting, the right wing had gotten our memo from the thirties, forties, fifties, and sixties. They sat down in Wyoming at a bunch of strategic retreats, and they decided that they had to build a grassroots base. Our side, meanwhile, had won a bunch of laws in the the 1960s and early seventies, and decided, “Shit, we won everything! We don’t have to do anything anymore, all we have to do is move to Washington, hire professional staff, hire a bunch of lawyers, professionalize our movement, and implement our laws.” This was a gross misunderstanding of power.

Resist is not nearly enough. Using the word better—I felt horrified and embarrassed for the Democratic Party on Monday when I read the New York Times. That was my actual response. Horrified, disappointed, freaked out, and embarrassed that I ever was a member of that party, ever in my life. I’m so embarrassed by this.

Hell no, resist is not enough. People used to say to me, “How come so many people come to your meetings? We have a hard time getting people out at meetings.” There are a lot of answers to that question. But a central one is because people need to believe that there’s a credible plan to win. They have to have their expectations raised, and they have to understand that there’s a credible plan to win. The minute that they put those two together, they’ll show up to meeting after meeting after meeting.

I meet with organizers, and they’ll say, “Well, that might work in your campaigns, but in our campaigns people are working two full time jobs and they’re really busy and they have no time, and that’s why they don’t come to meetings.” And I always say to people: that’s just crap. That’s always true in the life of American workers. Everyone works too hard. Everyone is super busy. Everyone is trying to get five minutes aside with their kids. But there will come a moment in a campaign where, if you’re doing it right, they will put their lives down and do nothing but try to win a campaign because their expectations have been raised that they can actually make change.

CM: You write that the main difference between these two powerful movements—the labor and civil rights movement half a century ago—and today is that during the former period of their great successes they relied primarily on eloquently-termed “ordinary people.” But now they depend upon more of a professional class.

How much has a professionalization of labor and social movements led to a diminishing power among the working class while the corporate class’s power grows?

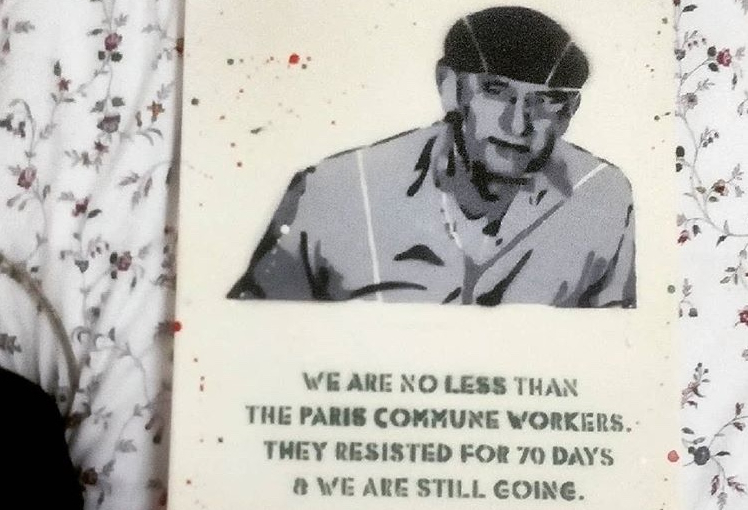

JM: It is a significant part of the problem. There’s a debate on the more progressive/left side of the movement which essentially says staff are not needed at all. There’s a sectarian line out there about how we don’t need professional staff at all. The workers will just rise up. Well, since the Paris Commune, I’m still waiting. I don’t think it happens that way. If you say that we don’t need staff at all, that probably means you haven’t been involved in a lot of really hard campaigns.

On the other hand, it’s a mistake to think that we can have a movement run by staff, where workers don’t have the primary agency or the primary say-so—where workers aren’t involved in making the strategy and involved in the power structure analysis. When workers decide that they want to play hard into a strategy and take a lot of risk, it’s because they’re actually in the strategy, they understand it, they’re part of it. I like to involve them even in the research phase.

Go check out a research department in the US labor movement. It’s buried somewhere with a bunch of white guys, probably with PhDs, who have a lot of caffeine and really strong internet connections, and they’re just doing corporate research. There’s no connection at all to the ordinary workers. Most workers in most union campaigns in our country—right now and for the last twenty years—are never brought into the strategy room. They’re never even shown the research done on the company that they work for.

We need researchers. Like I say, I brought four in from Canada to Philadelphia last year, because we needed some people just to dedicate themselves full time to that. But central to the strategy was that they were involving ordinary rank-and-file workers in the conversations about the power structure; we were talking to them as much as we were talking to journalists and policy people and former city hall people. And when we got to the end of the formal research process (meaning we know enough about who’s controlling power at the planning board, the zoning board, the city council, the hospitals, how it relates to hospitals, which hospitals need what from the state, from the city, from the fed, which CEO should go to jail versus not), the first thing we did was call a leadership meeting among the rank-and-file across five hospitals, and invited all the leadership in the organizing committee to come to the meeting to see a presentation about the power structure analysis of greater Philadelphia as we understood it at that point. That’s such a different approach to how we engage with workers in a campaign, and it reflects a class struggle approach, which says the workers have to make the decisions in the campaign.

It would be way better if the tens of millions of dollars that are being wasted on super expensive consultants to tell us what people think were instead being spent on real organizers knocking on people’s doors and not just asking what they think, but saying, “You want to take control of your lives, here’s what you’ve got to do. Let’s change it.”

So I think professionalization is a huge problem in the labor movement, and in the entire movement. Look at the environmental movement. Certainly this is as true there as it is in the labor movement. In the traditional women’s movement is totally staff-driven. The climate movement is totally staff-driven. When the labor movement became more staff-driven too, you could see us falling apart.

Furthermore, narrative has become a buzzword in the progressive movement in the last 25 years as a result of the consulting industrial complex, and the Democratic Party moving into the top leadership of the labor movement and then spreading throughout, whether it’s Planned Parenthood or the climate or the environmental movement. These are the same pollsters and the same people on that ridiculous campaign for Ossoff in Georgia who just pissed away $50 million we could have used for really good work. That same elite class of “strategists” (who are not organizers, by the way) are telling people that all we have to do is narrative change. All you have to do is get a good story. All you have to do is focus on the media.

Organizers like me—and there are many of us—believe that is the least important thing we have to do. The most important thing we have to do is be on the doors, in workplaces, out in the community, actually engaging people. And doing it systematically: helping to identify the people who organizers like to think of as organic leaders in the community and the workplace, helping scale them up, helping assess and bring them along (because they have natural talent already) so that they can go out and themselves organize dozens, hundreds, thousands more to get our movement back to the kind of size and scale that represents real power, not just a headline in the newspaper.

When you stop talking to the workers and instead you poll them—in the late nineties, they were replacing organizers in the unions with pollsters! Over at the SEIU, they thought, “There’s a poll a day being done by some local union across the country, let’s just poll the members and see what they think.” This is as useless as polling Americans during a hot, contested election, and asking them on the phone who they’re going to vote for. It’s not a very helpful exercise.

It would be way better if the tens of millions of dollars that are being wasted on super expensive consultants to tell us what people think were instead being spent on real organizers knocking on people’s doors and not just asking what they think, but saying, “You want to take control of your lives? Here’s what you’ve got to do. Let’s change it.”

We actually still know how to win really good campaigns. We’re just not doing very much of it these days.

CM: A past guest, journalist Stefania Maurizi, had just interviewed Julian Assange when she was on our show. Julian Assange had said something about power structure analysis that you write about in your book. On power, Assange told Stefania: “Power is mostly the illusion of power. The Pentagon demanded we destroy our publications. We kept publishing. Hillary Clinton denounced us and said we were an attack on the entire international community. We kept publishing. I was put in prison and under house arrest. We kept publishing. We went head-to-head with the NSA getting Edward Snowden out of Hong Kong. We won and got him asylum. Hillary Clinton tried to destroy us and was herself destroyed. Elephants, it seems, can be brought down with string. Perhaps there are no elephants.”

If power is an illusion, as Assange argues (and has shown through WikiLeaks), how can that fit into any power structure analysis we need to better understand our own power and the kind of power we are challenging?

JM: I think that quote is interesting, but I have to slightly disagree. Because, well, he’s been living in a teeny room locked in an embassy for a while. And yes, I understand that some people out there get to keep publishing because of the internet. But look at Brazil right now. Look at the serious power structure crisis they’re having. They illegally deposed the first female president, on totally no grounds. Every one of the men who just impeached her is a worse criminal than anything they could possibly find on her. So they undid a democratic president. There have been millions of people in the streets. They’ve been striking. Then the police and military are called in. They’ve taken control of the constitutional courts. The trade union movement is trying to defend Lula and defend their democracy—you know, they only came out of a military dictatorship in 1988, for godsakes, if you want to look at the power of the military. This is real power.

So I can’t quite agree with Assange on that. I’m glad for a bunch of the stuff he’s done. But the truth is, the power of the state is pretty intense. Power is real. Still, there are ways to contend with it. And there are more of us. And we saw it in the civil rights movement in this country; we saw it in the heyday of the labor movement. I’ve seen it in many union campaigns. We are more than them. We just have to have a movement strategy to get us close to something like eighty percent participation—because when we have that kind of participation, then we can challenge the power structure, and win.

CM: Jane, thank you so much. This has really been a pleasure.

JM: It was a pleasure being here. Thank you so much.