Transcribed from the 21 October 2019 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

It’s not quite right to say that this is all just a battle against police or against property owners or corporations or the state. It’s something else. It’s more about building up movements that practice radical politics and a radical adaptation of the city. Squatters are able to offer these spaces for many groups, many social movements, many people, many users who become politicized in these spaces.

Chuck Mertz: Squatting is a movement across Europe, but it’s far more than desperate homeless people seeking only shelter. Here to tell us about squatting and squats and find out what they’re all about, sociologist Miguel Martínez is author of Squatters in the Capitalist City: Housing, Justice and Urban Politics. Miguel is professor of sociology at the institute for housing and urban research at Uppsala University in Sweden. He was previously affiliated with the City University of Hong Kong and Complutense University of Madrid. Since 2009 Miguel has been a member of the activist research network Squatting Everywhere Kollective [SqEK].

Welcome to This is Hell!, Miguel.

Miguel Martínez: Hey, thank you.

CM: It’s great to have you on the show, Miguel, this is a fascinating book.

You write, “In 1989, I entered a squat for the first time. I was an undergraduate university student, by then very curious and enthusiastic about sociology but also about leftist and libertarian politics. Minuesa, as the squat was named, intrigued me from the very beginning. It was located in the city center of Madrid next to the picturesque street market at the Rastro. I used to visit frequently, on Sundays.”

If it was in such a beautiful location, why wasn’t this abandoned place inhabited? What does that reveal to us about the squatting movement when this beautiful place in Madrid would be abandoned?

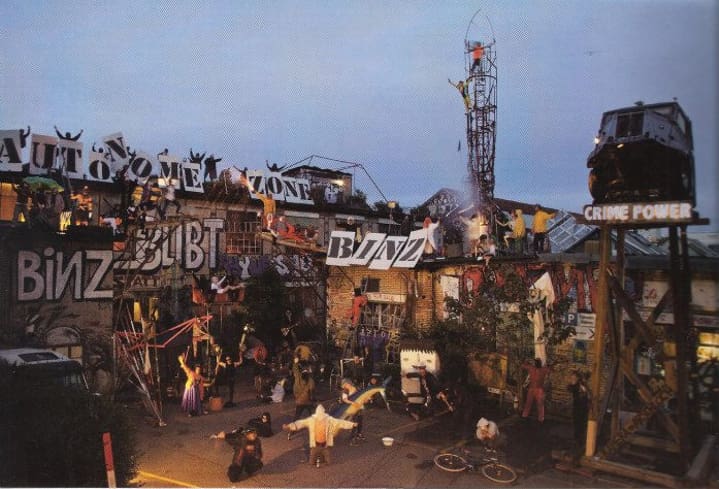

MM: At that time, there was a workers’ strike; there was a printing company that didn’t want to pay salaries to the workers, so they were on strike, and they occupied the premises as well as a huge building next to the premises of the factory. And some radical activists in Madrid who were squatting in different parts of the city decided to go in solidarity with them—they joined the struggle, and wanted to do something in addition to fighting to get salaries back: they thought, let’s occupy, let’s stay here, and let’s open a social center. This is something else, something beyond just dwelling in a place.

It became a fantastic space for lunches, talks, cinema, concerts, and politics—lots of debates and political talks. I was very young at that time and I was really fascinated by everything going on. I realized there were hundreds of squats all over the country and also all over Europe (and of course in other countries as well). I started doing some research and trying to collect materials—pamphlets and all kinds of interviews over the years—to this day I’m still writing on the topic.

CM: How often is squatting in response to labor issues? We spoke with Naomi Klein and Avi Lewis about their movie The Take back in 2004; that was about an Argentine factory where the workers occupied and actually got the factory running again.

So how often is squatting a response to labor issues?

MM: To be honest, not that often in the last couple decades. It happened more often in the past, especially in Italy in the sixties and seventies, and also in Spain in the late seventies. But that was a different movement—it was more of a labor movement then.

I also visited some of those occupied factories in Argentina, every time I went there, and of course that’s something different. In Argentina you can find schools or libraries or different kinds of social centers even within the factories. That’s a very special case.

Most squats are mainly dedicated to living: people need a place to stay, and they cannot afford to pay rent or to buy; or they combine something between living space and meeting space, or political or counter-cultural space. All of these things can be together. But labor struggles unfortunately are not so often connected with the squatting movement. Sometimes they are, of course.

CM: You have visited hundreds of squats—I would think that the police, that law enforcement, that the state wouldn’t be very tolerant of squats. How difficult is it? When you found out there were hundreds of squats, were you surprised that there were that many? And how good a job did they do of staying beneath the radar of local law enforcement?

MM: It depends on the country—legislation varies a lot from country to country. For example in the Netherlands, and in the UK, there used to be lots of opportunities to remain for years and years in a squat, because there were so many loopholes in the law that allowed people to stay, and to go to court and claim for adverse possession and all that. Sometimes it was not that dangerous, let’s say. But even in these countries with favorable legislation, there were many evictions, with lots of repression, very heavy-handed police. Once you are in the struggle you have to accept that it can happen at any time.

Still, even in places like Spain or Italy or Greece, where squatting is completely forbidden—it’s against the law, it’s against private property principles and all of this—sometimes squats have survived for more than twenty or thirty years. Most people know that threats of eviction and attacks by the police can happen, but they also usually know about legal procedures and about what’s going on in the political environment, so they can predict more or less when something’s going to happen. Then it’s a matter of resistance or other strategies, whether people decide to fight back or just to leave the place if they don’t want to get charges.

The interesting thing, though, is that it’s not quite right to say that this is all just a battle against police or against property owners or corporations or the state. It’s something else. It’s more about building up movements that practice radical politics and a radical adaptation of the city. Squatters are able to offer these spaces for many groups, many social movements, many people, many users who become politicized in these spaces.

CM: You were just saying that there are varied messages, and different squats can have different strategies and different approaches. But is there a common intended message that squats have when it comes to sending a message to capitalists or about capitalism?

MM: Well, yes. Something that all these experiences of squatting have in common is that it’s always a challenge to how cities are managed, how cities are bought and sold, and how cities are planned. This is a protest against the capitalist city, for sure.

There are many ways of conveying this message. Some people focus on living spaces, because they think this is the most urgent issue. The main purpose of some squatters who just occupy empty apartments or empty houses is to get access to a home. In case there are possibilities of access to social housing, sometimes we can interpret this as not a very radical message. But this is not always the case, because at the same time they are protesting. They are practicing direct action; they are questioning why these properties are empty and why there is criminalization against squatters. They are using a space which is otherwise used only for speculation and for profit-making.

Increased criminalization has a lot to do with the increased financialization of cities in real estate and housing. In that sense, I think squatters—even without noticing in the beginning, somehow—were early riders in the fight against these financial powers globally. That’s quite remarkable.

On the other hand, when you open up a space you occupy to different purposes, it’s becomes a different kind of protest. Then it’s not just about the claim of the space you are occupying. It’s about making more open spaces for everyone who is protesting in the city: environmental movements, feminist movements, and all kinds of labor struggles as well. There can be a combination, a mixture of positions joining forces in these places. In that case, the question is of the capitalist city.

It is also a praxis, a direct performance of appropriating the city, and claiming the right to the city for all those who are excluded, especially if they live in the peripheries of the city. That’s why a squat at the city center, at least in my view, is so important.

CM: An extended version of your dissertation was released as a book in 2002. You write, “Publishing in Spanish and with an independent house was tougher than I had imagined; the topic was not that attractive for the mainstream debates related to urban studies and social movements.” You add that your 2002 book and an ensuing edited book in 2004, also in the Spanish language, “sold out and were very popular among activists but hardly had repercussions in academia.”

What does that tell you about squatting? What does that reveal to you about squatting or about academia when it seemingly ignores squatting while it is incredibly popular with activists? What does that tell you about the study, today, of social movements?

MM: It has some lessons for me. I was starting my academic career, and I was expecting much more resonance in academia with all these studies. Unfortunately there are many barriers in academia, there are many standards about the way you have to write, the journals where you have to publish, the style of writing, and about the kinds of topics as well. My first book was at not only an independent but also an anarchist publisher. Apparently to be close to anarchism or sympathetic to anarchism was something considered taboo. It was really tough to engage people in these kinds of discussions.

At the same time, I had to move from one university to another, so it was always a very precarious academic position. But I decided that it was not only my academic interest but it was also a political and social interest, and that’s why I continued doing these seminars, meetings, and debates within the squats for many years, until I left Spain in 2010. The situation was somehow unsustainable economically, but I’m still happy that it was possible. And I believe that the purpose of academic writing is to reach people, and to reach activists and to reach everyone who could be interested in a specific and crucial topic in politics. To me that was the most important thing.

Now with this book, we are regarded today as a bit more academic. In recent years I have also written a few academic articles—I still feel they have a political purpose, not only to illuminate what’s going on in this movement and all its messages and practices (and its contradictions and limitations as well), but also to indicate what kinds of positive achievements the movement has made from an anticapitalist perspective. This is still one of the main drivers of why I am persisting in academia and writing and publishing about this topic.

CM: You mentioned the contradictions, and you write about that in your book. What are the most common contradictions that you experienced while visiting and doing your research on squats?

MM: That’s a difficult thing. In these kinds of movements, and in radical movements in general, there is sometimes some reluctance to engage with academics. Even if you are an activist yourself—I have squatted in different places all of my life, and been a regular visitor to many squats. But sometimes there is this distance from academia: “There’s nothing in there that can be beneficial to us” is a common refrain.

I think this is problematic, because it leads to a lack of a strategic political reflection, not only about your own specific case but about movements across the city, movements across the country or across the continent—and this is quite important. We need to join forces and we need to unite movements and see the obstacles, and see how to overcome these obstacles. This is why I believe that academic writing can help.

On the other hand, there is no perfect movement. In squatting, for example, you see that some experiences are very short-term. They are evicted very quickly; they don’t have time enough to develop a political discourse or a political practice in the local environment. This is quite sad. This is basically due to the powerful enemies that they have to fight. Sometimes squats are not so open to other movements, or they don’t even cooperate with each other. We also observe that there are splits or fragmentations within the movement for different reasons. The case of Paris, that I mention in my field notes, is quite illustrative of these splits. For example, art goes in one direction and residential housing activists go a different direction, and more autonomous or anarchist activists go in yet another direction. I think this is a limiting aspect to the movement, something that is important to reflect on.

And if I may, one final thing is that sometimes when squats are legalized, there emerges some detachment from the radical practices of squatting or autonomous politics. This is something mentioned very often by everyone.

CM: Who squats, Miguel? I think that there is a stereotype that squatters are young people on the far radical left. But who squats? And is there such thing as a far rightwing squat?

MM: Everyone can squat. It’s true that young people from the far left are the most frequent squatters and users of squats in Europe. But one thing I noticed every time I was squatting is that people from all ages, all conditions, all interests and backgrounds, join squats. Who the main activists are within a squat is a different question. Yet another aspect is again the purpose of the squat. When it’s about housing, for example, you see a wider range of people: families with children and all kinds of people who are basically poor, migrants and single mothers, etcetera. It’s quite difficult to say squatting is just about young people, and I think this is not fair and not true.

It’s important to distinguish movements in each city according to purposes and according to their attraction of different publics to their squats. That’s the main thing.

And as for fascist squats or rightwing squats, this is a relatively new phenomenon in Europe. They started in Rome and elsewhere in Italy, and we’ve seen a few more in Germany and Spain. But to be honest, this is not a general practice—it’s a very isolated practice. In fact, now in Italy, the fascist squatters Casa Pound have established a political party—which is completely contrary to the practice of most squatters all over Europe. So we cannot generalize about that.

CM: You mention housing being criminalized in many parts of Europe. How is housing “criminalized”?

MM: Of course there are some criminal practices in terms of mafias, people who occupy houses for selling the key or for subletting. These are basically criminal gangs—quite dangerous sometimes. But again, they don’t represent at all what the squatting movement is, which is more public, more outspoken, more clearly confrontational and disruptive, and engaging people in grassroots politics. So it’s a completely different phenomenon that I like to separate from the squatting movement.

Autonomous movements always stand for horizontality, assembly organization, bottom-up and grassroots organization, and the idea that all people who are oppressed or feel oppressed should take issues into their own hands instead of relying on broader or nationwide organizations.

But the issue of criminalization is quite important, because of course squatting usually means doing something illegal or at least unauthorized. Sometimes property is not very clear, and it’s not clear that you are doing something illegal, because the property has to be established and clarified. But sometimes it’s obviously an illegal practice, because all the legislation and criminalization goes against you.

The thing is, it has been a long historical process. Squatting empty properties was not always an illegal practice; it was not always criminal. It is something that has been getting more and more criminalized in different countries, for different reasons which are difficult to explain right now. But in the past, there were more opportunities for squatting according to the legal frameworks, because there were these adverse possession possibilities, and it was not a criminal offense, it was just a minor offense according to civil legislation, and so on.

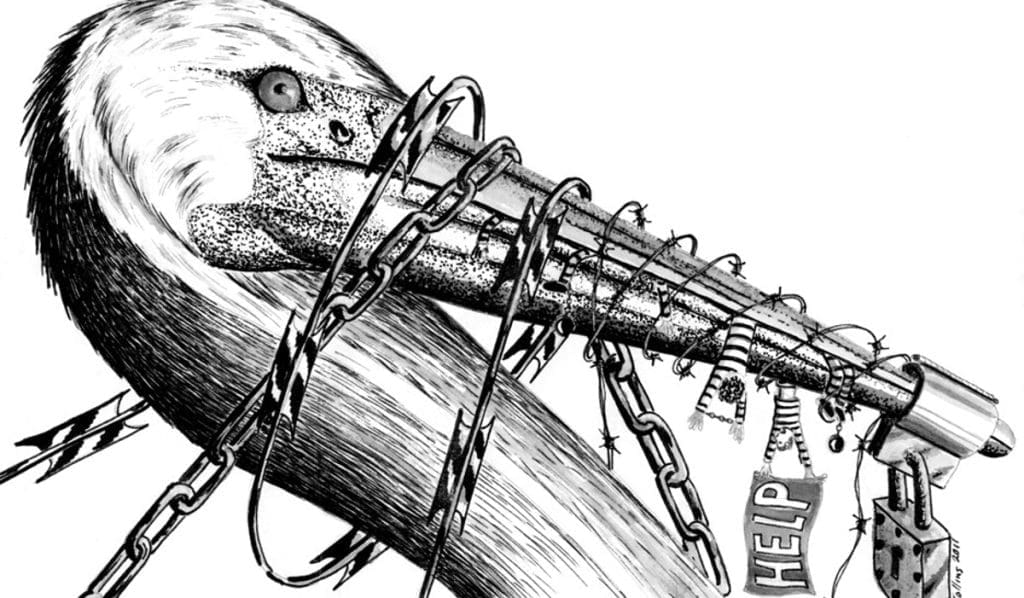

But most countries became more and more strict and decided to persecute squatters, because at some point they realized this was a “dangerous” movement. The financial corporations want to exploit the opportunities in cities much more. They regard squatters as one of their enemies because they are using these empty premises.

Part of the explanation for increased criminalization has a lot to do with the increased financialization of cities in real estate and housing. In that sense, I think squatters—even without noticing in the beginning, somehow—were early riders in the fight against these financial powers globally. That’s quite remarkable, from my perspective.

CM: So the commodification of housing in neoliberalism leads to the criminalization of squats, criminalization of housing. As a repercussion of neoliberal policies in Europe, has there also been an increase in homelessness? Is homelessness a new phenomenon in Europe that’s related to the housing crisis?

MM: Absolutely. Homelessness is on the rise, and it’s an incredible, terrible sign of the failure of welfare states, and of neoliberal policies. This is something quite problematic.

Some people who are not familiar with squatting tend to associate squatting only with homelessness—and of course there is an association, and it’s true that squatting is a material opportunity for people to get free from homelessness. Of course homeless people have an interest in squatting—but sometimes they need knowledge, they need support, they need legal assistance. They need movement. And activism is not just about entering the place. It is about defending the place. It’s about claiming your right to that place, claiming your right to housing, or claiming your right to the city.

That alone makes squatting about much more than just homelessness. Of course in this situation where homelessness is also being criminalized—they are forbidden from staying on the streets and forbidden from begging, forbidden from even existing—this is a terrible sign of how even welfare states in Europe are going down a path completely against their own history, against human rights. But this conservative trend is being disputed by many movements—among them, squatters’ movements.

CM: I would imagine that squats would in general have a bad image—I don’t know why, it’s just that here in the United States, anyone who is homeless is condescended to, is looked down upon. So I bet people would not like any kind of squat whatsoever here in the United States; they would be very upset about it. There’s a very bad impression both of homelessness and of this kind of organizing that’s outside of what is seen as regular organizing.

How often, though, do squatters’ beliefs and approaches to living have an impact on the way their non-squatting neighbors live? Can, say, a communal squat lead to others in the area to consider or adapt communal approaches of their own? Or are they just hated? Are squats hated or do people learn from them?

MM: Well, yes, both. Sometimes it takes a slow process of convincing and showing your will and your practices and your intentions, and approaching people and to inviting people to your activities. I don’t think squatting is about convincing everyone to be squatters themselves. It’s more about creating a movement and joining radical politics all together. I think there are many chances. And evidence from my own experience suggests that you can attract a great deal of neighbors to be sympathetic, to support, and to join the activities in the squat—as well as join your campaigns and, yes, even squat other houses for living purposes.

But on the other hand, to the extent squatters are questioning the private property system in general, many people who are investing in and buying property feel that squatters are questioning their own lifestyle and everything they believe in. At that point it’s quite difficult. They are possibly the primary enemies of squatters. They don’t want squatters in their area. Unless they also notice that there are many other deficiencies in their area that the squatters are also discussing, and they can join their campaigns, and in that case they become alive. But of course it’s impossible to predict this. That’s why every decision about the building where you are squatting should be taken in a very careful manner, understanding the history and the place and the people around the neighborhood, and the property issues.

And then it depends on luck, of course.

CM: You mentioned earlier that what squats generally want is autonomy. What do squatters want autonomy from?

MM: There is a chapter in the book called “Autonomy from Capitalism.” That’s one answer. This touches many struggles: labor struggles, feminist struggles, urban struggles all through the decades—at least the last four decades. There is an underlying anticapitalist sentiment, an anticapitalist direction, with any of these autonomous movements.

On the other hand, autonomy can be predicated in different ways. For some people autonomy is just autonomy from the state. They don’t want any relationship with the state. They don’t want legalization. They don’t want subsidies. They don’t want recognition from the state. This specific form of autonomy is not necessarily anticapitalist, but it can be.

Sometimes squats just provide services to the people around: culture, sports, meeting space, concert space, community gardens, and so on. This is not itself a revolution; it’s just an alternative. But an alternative economy, an alternative milieu, an alternative society, an alternative politics is quite important for creating a revolution.

Sometimes autonomy has a feminist background, in which people decide to be autonomous from all forms of oppression and oppressor groups. In that sense, in order to get liberation, you need to be completely independent and autonomous from all these structures. It can be a major issue; even in the squatters’ movements, many women* have felt they needed their own feminist squats just for women*, because there has been a lot of sexism within the movement. That’s something that the movement needs to realize and needs to fight back against. I totally support these kinds of autonomist perspectives.

But in general, a clear lesson I have drawn from past autonomous experiences all over Europe is that formal organizations, political parties, corporations, and state regulations are not that good—I mean, in general it’s better to be independent from them in order to fight them, and to question all the destruction that they are creating. In that sense, autonomous movements always stand for horizontality, assembly organization, bottom-up and grassroots organization, and the idea that all people who are oppressed or feel oppressed should take issues into their own hands instead of just relying on broader or nationwide organizations.

This is one of the strengths of autonomous movements. Most squatters are more or less enticed by these ideologies. That’s not always the case; for some people it’s not so explicit, or they prefer a more classical view of anarchism, or they are not the person who buys into structural ideologies, they just prefer the practice of radical action and self-organization—which is fine, too.

CM: You write, “Authorities and power-holders exert their influence to suppress, regulate, or prevent the extension of squatting.” To what degree does the state see squats as a threat to their power? And are squats challenges to the state?

MM: For the state, squatters are basically challenging their authority. The state regulates land use; it regulates licenses and permits to use houses; it also takes property taxes and taxes profits in the construction business. Squatters are basically circumventing this system. There is a reason—people are homeless; people cannot afford housing, they are being exploited. People feel they are poor, and they work. They challenge the state because of their conditions and because they want a different world. It’s completely normal that a state authority feels that this is a threat.

A different issue is how the state deals with squatters. If squatters are a big enough threat, then the state cannot suppress them immediately. They have to negotiate, they have to compromise, or they somehow have to tolerate the existence of the movement. By the same token, the movement is not going to change the whole society all of the sudden—it might be only a few properties which are occupied. In that sense, state authorities can be very strategic, and movements are also strategic given their situations.

I mention very often the case of Denmark, in particular Copenhagen. With the exception of Christiania, in the space of a few years the movement was completely smashed, and almost disappeared. But just before this heavy repression of the movement, the state legalized a few spaces and was offering housing opportunities for many others. And they let Christiania remain—until recently; eventually it was also dismantled and forced to become privately owned. Nonetheless, that happened after almost fifty years of occupation, which is quite outstanding from my perspective.

CM: So is the revolution already happening, and it’s happening within the squatting movement? Are uprisings that seem disconnected in fact all part of the same revolution—a housing revolution that is now embodied in squats?

MM: Unfortunately, I don’t see a revolutionary moment. But I have to say that in these circumstances squats are quite useful; they are quite valuable resources, infrastructures. Sometimes in squats you see revolutionary activities, and you feel a revolutionary environment. But not in all squats. We cannot be so optimistic. Because this is not reality. Sometimes squats just provide services to the people around: culture, sports, meeting space, concert space, community gardens, and so on. This is not itself a revolution; it’s just an alternative. But an alternative economy, an alternative milieu, an alternative society, an alternative politics is quite important for creating a revolution.

There are seeds of revolution in a squat. Sometimes they are crucial infrastructures for revolutions and uprisings, as we noticed in Madrid in 2011. It was an incredible discovery for me at the time: the whole squat was filled with people who were completely new to politics and to the occupation of the Plaza Mayor, the main square of the city, and demonstrating all the time. They basically shared our revolutionary attitude within the squat. But that was completely unpredictable. It happened, and it was quite important, but then it also vanished after a few years.

But the squats are still there. So even when revolutionary moments or important uprisings take place, squats can be a more material, solid, and enduring space for providing and creating these prefigurations of a possibly better world, a revolutionary situation.

CM: You write, “The hot issue for the decisionmakers is why they prosecute those who find an affordable means to house themselves while there are abandoned empty apartments and a scarcity of social housing.”

What does it say to you about a society that has a surplus of housing and yet still has people who do not have and desperately need a home? What does it say to you about a society that tolerates homelessness while having abundant amounts of housing?

MM: To me, this is a criminal society. I think it’s completely unacceptable. It’s also a sign of how capitalism doesn’t care at all about waste or overproduction, or about production that doesn’t meet the needs of people. Unless we take over the means of production and we take over the state’s functions, it’s almost impossible to change this.

I don’t think this is acceptable. It’s completely inhumane. It goes against all human rights and all basic understandings of civilized society.

All people, all homeless people should be housed. All people should enjoy the right to housing in decent conditions, good locations, and good quality. We need to redistribute resources in that direction. In the meanwhile, if this is not possible, I think squatters and all kinds of movements of resistance will challenge this and will discuss it and will present this as something which is completely against any rationality. I am on that side.

I am not totally against good housing policies. I think they can contribute well and this is something we need. But I don’t see goodwill by the politicians of most countries to solve this situation. Of course, there are exceptions everywhere. In some places, the vacancy rate is much lower. In some cases, like in Spain, it’s unbearably high. People should do something to fight this.

CM: Miguel, I really appreciate you being on the show this week. Thank you very much.

MM: Thank you, it’s a pleasure.