AntiNote: Today we write from one of our international collective’s several geographical nodes—from the heart of the Minneapolis Rebellion—on the topic of a similar rebellion that took place forty years ago in one of our other nodes, Zurich, Switzerland.

‘Nodes’ is a pretty impersonal word. In fact Minneapolis is the hometown of one of our editors, and Zurich is the hometown of another. What is being transmitted in the text below is love, siblinghood, and solidarity across oceans and borders, in addition to incredibly valuable information for those in Minneapolis now at the very beginning of a process which autonomous movements in Zurich have already experienced, seen play out in manifold ways, and reflected upon in the decades since as they continue their struggles for liberation within and around (and sometimes against) the spaces and infrastructure that were won and built in 1980.

1980 was a turning point that “put Zurich on the cultural map,” in Europe, transforming the city from a strict, dead, orderly wasteland of banal bourgeois boredom into a (more) lively, living human social environment complete with autonomous spaces and social centers. The Hot Summer of 1980 featured repeated mass actions and clever counterinformation campaigns as well as full-blown police riots and a notorious prototypical case of doxxing in which an activist woman of color was targeted for threats and harassment and literally bullied out of the country.

There is a 2010 book, Zur(e)ich brennt, which covers this and all other key events of the Hot Summer, from the lead-up to the Opera House Riots of 30 May 1980 (note the near-perfect timing of the Minneapolis Rebellion, almost exactly forty years later to the day!) until the opening of the Rote Fabrik as a semi-autonomous cultural center in late October of that year. It also covers the slowly unspooling aftermath of the struggle, both in terms of its achievements and its costs. It is a stunning collection of street-level voices, in many cases captured in the vulnerable moments of awakening radicalization, full-blown rebellion, or sneaking regret. The voices of their antagonists in the press and city government are also present, in all their unvarnished bewilderment and spitefulness. The parallels to the present discourses in Minneapolis are endless.

What follows are the foreword and first chapter of Zur(e)ich brennt. We have liberated them from any copyright through translation from German into English, and hope that the authors whose words are being so used are not upset. We do not care what the publisher (a large multinational conglomerate) thinks. If there is sufficient interest, we may attempt to translate and make available further chapters over the course of the Hot Summer of 2020. A full and legitimate translation of the book, as a book, for anglophone consumption, is likely not in the cards. We have tried.

As with so many other flashpoints in the history of autonomous movements, there is much to learn from the experiences and reflections of the 1980 ice-breakers in Zurich—and now more than ever. So much revolted energy has been accumulating for so long in locked-down neoliberal cities worldwide, and then the added social, political, and economic pressure of a global pandemic—and the brutal police murder of George Floyd—caused Minneapolis and other cities across the United States and across the Earth to explode.

Activists everywhere are seeking the inspiration, courage, and counterinformation they need to take the actions necessary to liberate themselves and their neighbors. We dedicate this article both to the memory of George Floyd as well as to the freshly founded autonomous zone in Seattle, where activists are further along in the Zurich timeline now than even Minneapolis, where it all started. We salute you!

10,000 squats against their world of repression! We will not stop until everyone and everything is free! We take care of us! Que se vayan todos!

Foreword

by Lars Schultze-Kossack

2010

I wasn’t there when Zurich burned. I was still much too young, and I’m from the “big canton,” Germany. Even living in Hamburg, I only went down to the Hafenstrasse every now and then. I had the privilege of learning about the Hamburg Pocket only after the fact.

Nonetheless, D’Bewegig [the Movement] caught my interest. Exactly thirty [now forty] years ago, something began—unexpectedly for some; as part of a clear causal chain for others—which transformed Zurich and still shapes the city to this day. The Hot Summer of 1980 put Zurich on the cultural map of Europe, right there where cities like Hamburg, West Berlin, Amsterdam, and London already had their place.

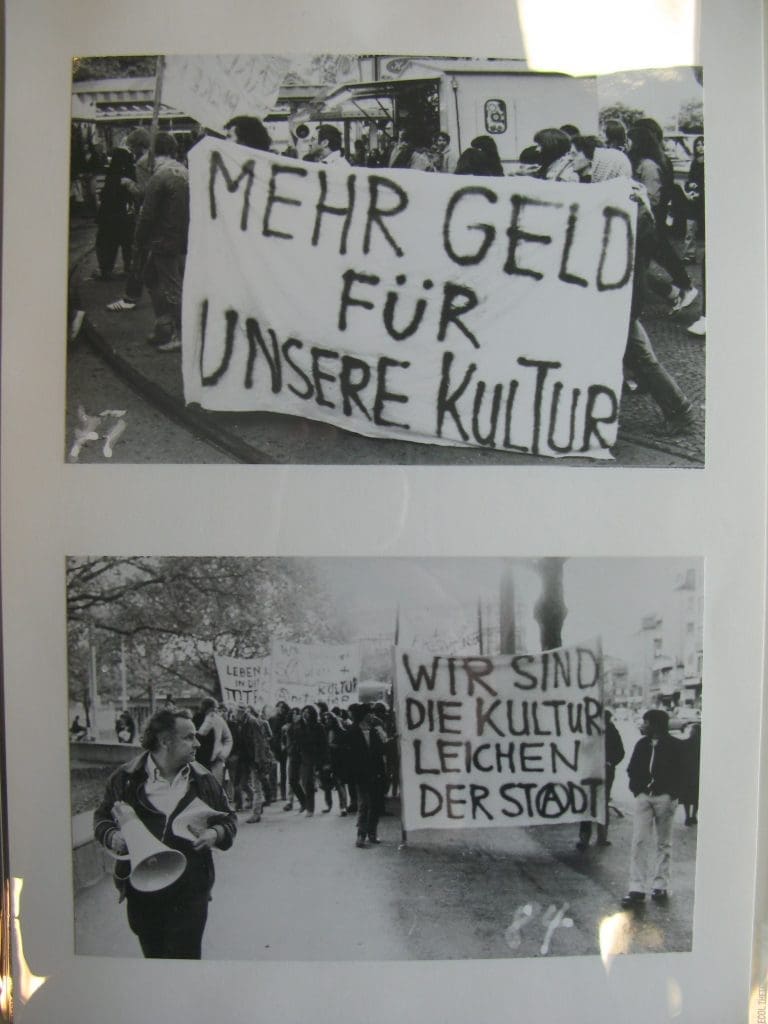

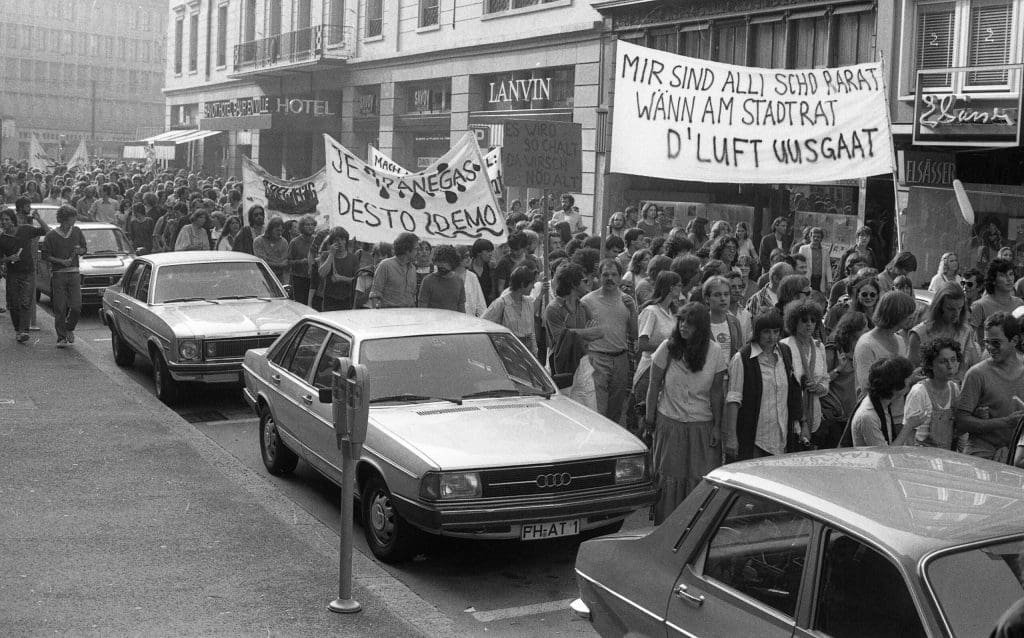

The unrest that spread across Europe in 1980—of a scale that prompted Der Spiegel to name an entire issue “Youth Riots [Jugendkrawalle]”—began with the Opera House Riots in Zurich on May 30. Both the cover of that issue of Spiegel and its feature interview with Zurich youths appear in this book, along with an interesting commentary on this peculiar media sensation. Also to be found in the coming pages will be many photographs by Klaus Rósza as well as a comprehensive collection of fliers and other artifacts of the movement. The creativity with which the activists worked was and is simply astonishing.

In this book you will also encounter articles by media tycoons like Hugo Bütler and Ueli Haldimann as well as an interview with Thomas Wagner, who was a city council member at the time and, in 1982, was elected mayor of Zurich. This interview brings into focus the dilemma that was facing the authorities in 1980: how much autonomy can a state afford to tolerate? What are the limits of tolerance? For Wagner, the state would come under direct and immediate threat if it were to keep allowing “extralegal” space to open up. As far as he was concerned, this was beyond discussion.

On the other side, at least within the city government, there was the group around Sigmund Widmer, the sitting mayor at the time. He stood for “dialogue and tolerance”—though of course this did not mean the police didn’t react violently to the activists in the streets. The dilemma is depicted well by one of Sigmund Widmer’s statements in an interview with Züri leu: pointing to referendums back in 1974 in which plans to build a cultural center were voted down, he pleads, “Democracy takes time!”

But this is perhaps the greatest paradox of politics: Youth ain’t got time. Young people want culture and motion and they want it now. So it was really only a matter of time before the campaign for an autonomous youth center (autonomes Jugendzentrum, or AJZ) in Zurich, frustrated for so long, erupted into confrontation.

In retrospect, while the violence on all sides is to be condemned, what happened in Zurich is no different than what happened in other European capitals: the youth rose up, demanding recognition and space for their culture; they wanted more of a say. For his part, Thomas Wagner, moderating his law-and-order attitude, eventually detected the growing chasm between the city’s youth and the rest of society, and came around to the idea that facilities like the Rote Fabrik were sensible and necessary. This so-called “gap” existed elsewhere, after all—and thus, Zurich “burning” is not just a local issue but belongs within a broader context of events affecting all Europe.

With that, let it be said that Zurich sits at the center of Europe and was, is, and remains a pole of attraction for young people all around. So when [rightwing politician and media mogul] Roger Köppel complains for the nth time in the pages of [arch-conservative periodical] Weltwoche that too many Germans come to Switzerland because their country is bankrupt and they are robbing Swiss citizens of their freedom, just remember that cultural exchange requires people moving back and forth, as my Swiss friends in Hamburg will gladly confirm. Cultural exchange entails the transfer of knowledge and information all across Europe. As one of the wealthiest countries in Europe, Switzerland is participating actively in this by enticing well-educated workers from Germany with more jobs and better pay. That’s the market economy, that’s capitalism. Today’s task is to promote this kind of exchange in Zurich, in Switzerland, and in all of Europe; we can let Köppel be Köppel.

These days there is a lot going on in Zurich. The city is alive. The Rote Fabrik has become fully incorporated into the local everyday, and is a wonderful place to spend time. On Gessnerallee, one encounters office workers sipping beer in the evening, listening in on a touring band’s soundcheck. Tolerance, worldliness, and cosmopolitan culture are what make the city livable, and bring new changes time and time again. This is good, because Zurich is definitely too rich, but not too rich to change.

PS: We have gathered together widely differing perspectives in this book. It is the only way, we think, to get a complete view into the events of 1980 Zurich.

Zurich is Burning: A Loss of Innocence

by Alain Marendaz

1981

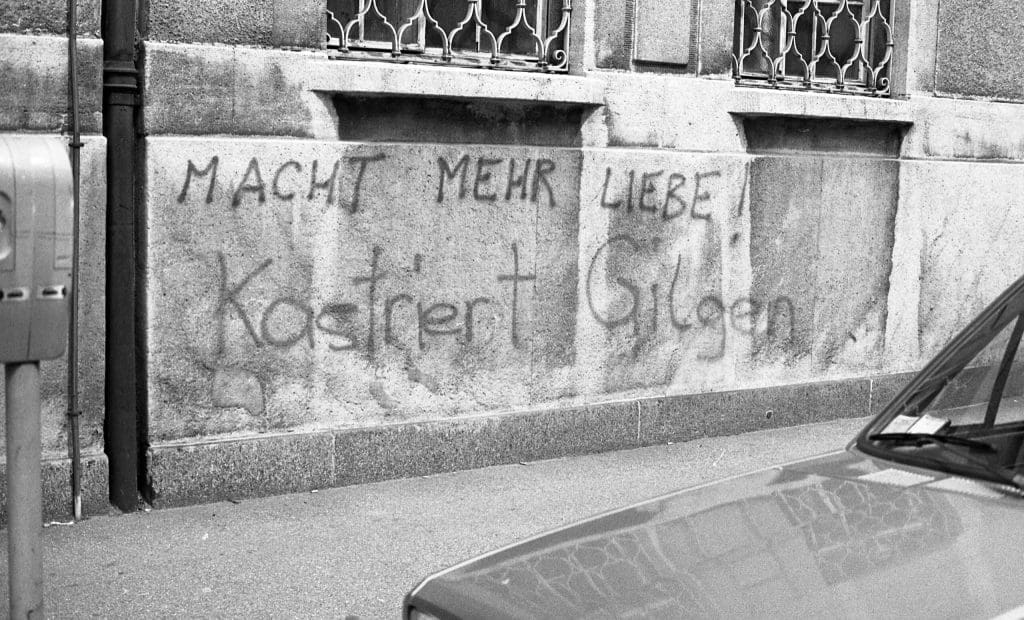

June 10, 1980. The city of Zurich is at a low boil. Even the university is simmering: the director of education, Alfred Gilgen M.D., had, with a (purposeful?) lack of political instinct, forbidden ethnology students from showing video footage of the riots. Day of Action – megaphones – balloons – spraypaint – rally in front of the administration office (“Use mit de Gfangene / inne mitm Gilgen!” – “Release the prisoners / put Gilgen in their place!”) and then on to the offices of the [center-right newspaper] Neue Zürcher Zeitung (“Hüt gits kai NZZ!” – “No NZZ today!”).

I tag along, out of general sympathy for the youth movement and out of sincere outrage at the attempt to muzzle ethnology studies. It is a naive exercise of my civil rights—demonstration euphoria. Liberty, Equality, Peppermint tea!

Night falls. A dumpster is burning in the entryway of the NZZ building. I help put it out; I don’t see the sense in such destruction. Around 11:30 p.m. the demo seems to be breaking up, so along with a few friends I withdraw to a bar for a quick nightcap. Just after midnight, on the way home across Bellevue plaza: rows of police in full riot gear, the air thick with stinging teargas. I barely have time to tie a handkerchief over my nose before it kicks off: rubber bullets, more teargas canisters, personnel transporters—a police riot. We scamper around the Sechseläutenwiese (I won’t tread on this sacred lawn even when running from the cops), then stop to catch our breath at a tram stop. The police assault redoubles; I don’t see my friends anymore; I run up the hill on Rämistrasse and throw myself behind a parked car to dodge another salvo of rubber bullets. In front of me now: the car, whose windows have not held up under the barrage. Behind me, a nightclub, the sign in English: “Everything a man enjoys.” This is the last thing I see.

Then, a ferocious baton strike from behind that somehow still catches me across the face. The taste of blood; leather-gloved hands punch and grab me in a choke hold; kicks—I am far too shocked to defend myself. Where the hell did they come from? (Two days later I read it in the newspaper: “encirclement,” the modern form of an old hunting tactic.)

There is already one person in the transporter; I am thrown in next to him and the door slams shut. Then the van takes off at full throttle; it must be doing circles around Bellevue, because we are continually pressed against the same wall. From time to time we hear the dull thud of a paving stone striking the vehicle.

We lick our wounds and discuss what they’ve got in store for us. At can’t be much; check our IDs, perhaps? My mood brightens and my curiosity awakens: it’s not every day you get a glimpse inside the police subculture. The van stops in front of a waterfront esplanade, we haven’t gone far, and the doors open: “Out!” It’s raining. Officers rip the jacket off my body, pull out my wallet and ID. “Aha, a student! Take off your shoes!” What the hell? I am made to stand in a puddle of water, in my socks. Full search: they find nothing of criminological significance. A plainclothes officer pulls out a small, pre-printed arrest card. Rationalization in the classic Zurich style: mark the reason for arrest by checking a box! Which one is it, then? Stonethrowing? Violence against an officer? Looting? Multiple-choice criminalization!

On my card, there is already a thick X in the box next to Stonethrowing. Just enter the name, and hey presto! A criminal!

Ten minutes later, we are sitting once again in the transport van, doors open, wet and freezing, no jacket, no shoes. More riot cops appear, their faces made practically unrecognizable by their visors—all I see are mustaches. They peer at us in the darkness of the van. One of them points at my comrade-in-suffering and says, “That’s the one! Or wait, no, I’ll take the one with the glasses,” and shifts his finger to me. I don’t understand any of this; I listen as the riot cops work out which of us they will “take,” and then the door slams shut again. The van sets off for “home.”

We are ordered out again at the police station. I learn a new ambulatory style, the “football technique”: with every sock-footed step across the station courtyard, a kick in the ass!

I find myself once again in a cell, ten arrestees in about ten square meters: some of us are half naked, injured, with severely burning eyes, no first aid (all the yelling does no good). Two seventeen-year-olds take turns throwing up, switching off between the toilet and the sink. We are freezing; our appeal for blankets is refused (stock answer: “This ain’t a hotel”). Then, after around an hour: recording of personal information, a quick snap for the criminal photo album, and off to individual cells. I pull the bunk down in the dark and, exhausted but still not especially concerned, fall asleep.

A few hours later, I am awoken by a grizzly voice blaring from the electric innards hidden somewhere in the ceiling above me. “Get up, clean up, wash up!” A hint of daylight is evident through the triple-paned frosted-glass window. There is a jackhammer going outside: Zurich is awake. I look around the cell: a space of about two strides by four strides; a tiny desk and chair, bolted down too close to each other to sit comfortably; a fold-out bunk, a toilet bowl, a sink. I refuse breakfast (two slices of bread with no butter and a cup of brown liquid that is apparently supposed to approximate coffee) and solemnly declare a hunger strike, which produces a knowing smile from the guard. I ask for cigarettes and something to read (according to a declaration posted in the cell, I have a right to both). I won’t get the smokes until around four in the afternoon, but a couple of magazines arrive promptly: a special edition about Queen Silvia of Sweden’s first child, as well as a six-month-old, torn up and sperm-stained issue of Neue Revue. For the first time since my arrest, I actually feel insulted.

Over the course of the morning, I am officially admitted to the criminal club: booking and processing. My fingerprints are taken (or, as the officer put it: “Mir nämed dir jetzt d’Tööpli, ganz locker!” – “Just gimme yer paws, relax!”); a part of my identity thus disappears irrevocably into the police computer. My physical description is also dictated, with great precision but without the slightest regard for any complexes I might have, into the record. Then another round of photos, and back to the cell (the people in internal services have also mastered the “football technique” quite well).

Around noon comes the interrogation. A detective from the fraud division (!) explains to me why I am here by bluntly asking: “Do you acknowledge that on Bellevue plaza at 12:45 in the morning you threw a stone at police?” I am honestly shocked. “No, I didn’t throw anything. I have never thrown a stone, I am against violence—and besides, at 12:45 a.m. I had already been under arrest for twenty minutes!”

That’s a minor detail, he says; there were witnesses, two police officers. He says they’re on their way here to pick me out of a lineup, so I’d better confess now, it’ll be better that way!

I recall the van at the esplanade, the riot cops there: “Or wait, no, I’ll take the one with the glasses!” So that’s how it works.

The desk jockey does some playacting. He makes several phonecalls: “Are they here yet?” Then he goes looking for them; he deposits me in a waiting cell, comes and gets me again, “They’ll be right here,” and then, nothing. Three times through the same game, over two hours, only finally to be brought back to my cell from the night before without the lineup having happened.

Towards the evening I get picked up for my transfer to the district courthouse. A few final kicks in the ass and I’m back in a transport van again, this one with separation walls. The door is slammed forcefully. My ears hurt. Behind me, another prisoner, moaning, is also thrown in the van, followed by a dash of teargas, and then it’s off to the games: the broken-oxcart race across the courtyard! Accelerate – stop – accelerate – stop … at least ten times. They know perfectly well that we are not strapped in, that we are splitting open our heads (abuse in detention counts as torture, I once read). After a few minutes of normal driving, we stop again. Driver and passenger both get out and start to rock the van, first slowly, then with increasing vigor. I can barely see, there are tears in my eyes, I think I might lose it myself, listening to the prisoner in the compartment behind me start to have a breakdown. I try to decode the graffiti on the interior walls, to concentrate on these artifacts of prison folklore. Finally, after an eternity, the trip to the courthouse is resumed. We are taken out of the van. “I know why they pick me to drive these potheads around,” says the one cop to the other. Yep!

In the district courthouse, the atmosphere is jarringly friendly. Everyone is polite. The district attorney offers me his hand, smiles, addresses me in the formal: “Setzen Sie sich; Erzählen Sie…” (is this switch also intentional?). He listens, nods, writes down what I say. Then he asks me about the paving stone. He pulls out a sheet of paper: “Lineup Report: Positive ID.” I nearly fall out my chair, and explain to him that this lineup never took place. “I see, I see,” he says, and writes it all down. I notice that the time of incident listed on his papers has been shifted to twenty minutes earlier. “That can happen,” he says, “Police are only human.” I tell him about what I observed at the esplanade. “Aha,” he says, and writes it down. I tell him that I have five witnesses who were with me the whole time and saw that I didn’t do anything but run away. He wants names. I want to know what will be done with the names. “We’ll keep you another night in jail because of risk of collusion, pick your friends up tomorrow morning at their homes, and charge them with disturbing the peace.” So I can’t enter any witnesses? “People who were arrested under similar circumstances can’t be your witnesses.” I say something about collusion among cops. He murmurs something about insulting an official.

The district attorney lists off the offenses that he will most likely charge me with: Participation in an unauthorized demonstration (I stand by this one—and would do it again); disturbing the peace (I still don’t have any idea what this even is); violence and threats against officers under statute 285.2 (“…punishable by maximum three years in prison or minimum one month in jail”).

I am free to go. Standing on the street in front of the courthouse, I breathe deeply and try to orient myself. Shadows lengthen as I meander through the city; slowly it dawns on me what has happened: I am being accused of a crime I didn’t commit; I don’t have any way to defend myself without the same thing happening to my friends; I have been confronted with a cynical justice system that doesn’t line up with the image of it they drew for us in school…

I’ve lost my innocence—in more ways than one!

This article first appeared in Wespennest issue no. 42 (1981).

Translated by Antidote