AntiNote: The following is an extended excerpt of a radio interview, edited for readability.

On 25 January 2014, Chuck Mertz of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) interviewed Hilary Wainwright about her contribution to the Transnational Institute report State of Power 2014: Exposing the Davos Class, an examination of the nature of neoliberalism and the need to resist it in diverse ways, many of which may not be ‘political’ per se.

The “ecology” of resistance needed to upend the “complex and constantly mobile organism” of neoliberalism is one of the central themes we are exploring on Antidote; Wainwright’s explanations and imaginative terminology provide a useful framework for these continuing discussions.

Neoliberalism was a product of a class struggle from above, which was won by Thatcher and Reagan and those who wanted to get rid of any constraint on the market.

Chuck Mertz: Live from London, Hilary Wainwright is with us. Hilary is one of my favorite guests and if you don’t know her work, you should. You’ve got to get the book Reclaim the State: Experiments in Popular Democracy. And if you are an activist, even though the book is twenty years old, Arguments for a New Left: Answering the Free Market Right is still a fantastic guideline and textbook.

Hilary, you write: “It is true that the powerful exert their power opaquely. Secrecy is their first line of protection, and a lot has been done to make neoliberal market power mysterious, indeed to render it invisible. But the relationships and mechanisms of domination at any particular time are historically specific: a product of struggles won and lost, interests formed, entrenched and defended, alternative directions suppressed.” But historically, Hilary, and possibly simply due to technology, mass media, globalization…has power ever been any more entrenched and opaque than it is today?

Hilary Wainwright: That’s a good question. I think it’s in the nature of the way the powerful defend their vested interests; it’s always been entrenched, right from the first building of a moat around a castle, or castles on hills. [As for] the opaque nature: in the late-19th century British imperial power, in a sense, showed off—it was very demonstrative in terms of its status, but actually the way it worked was quite opaque.

I think the [neoliberal] market appears to be haphazard—its claim to uniqueness and glory, as it were, is that it’s invisible, ‘the invisible hand of the market’—but we know that markets almost inevitably tend to produce monopoly and oligopoly, the rule of the few. Even as the market produces its powers, they’re often disguised by a relationship with the state which makes the state the first port of call for the people. When a problem occurs, the people think “oh, it’s the government,” when actually increasingly now it’s the workings of corporations protected by government. So we are at a time when it’s at its most opaque, and as entrenched as ever.

CM: Hilary Wainwright was a contributor to the report State of Power 2014: Exposing the Davos Class at the Transnational Institute. Her chapter in that report is called State of Counter-Power: How Understanding Neoliberalism’s Cultural Underpinnings Can Equip Movements to Overthrow it.

You make a really great point that the state becomes the fall-guy for the policies of neoliberalism; it seems like the focus of social movements, activists, and protesters is on the state rather than on neoliberalism itself.

But the word ‘neoliberalism’ is never used within the mainstream media; it’s left out of the dialogue. So this is a very simple question: how would you define neoliberalism?

HW: I think a more accurate term is ‘corporate capitalism,’ because ‘neoliberalism’ is really referring to the deregulation of capitalism. After the War, particularly in Europe and also with the New Deal in the U.S., there was a recognition that the market needed to be regulated to benefit the mass of people. In a way, the War—as a war against fascism and as a war that mobilized a mass of people—meant that the mass of people’s expectations of democracy grew radically. People wanted something more than the kind of market domination that had led to massive unemployment and misery in the ‘30s. People wanted some regulation of the market, full employment, a Welfare State.

And that damaged Capital. It lowered profits, it ate into the interests of the rich, those who had benefited from the unregulated market. So neoliberalism was a product of a class struggle from above, which was won by Thatcher and Reagan and those who wanted to get rid of any constraint on the market.

Neoliberalism really meant the return to a pre-Social Democratic unregulated market. The result has been the growth of monopolies, the growth of corporate power, so in some ways the term ‘corporate capitalism’ is more accurate than ‘neoliberalism.’ But neoliberalism means deregulation, the ‘unleashing’ of the market.

CM: Because neoliberalism tends to lead to monopolization, how much does it threaten the basic tenets of capitalism, things like competition and innovation?

HW: Massively. This whole idea that the free market equals innovation, equals competition, is one of the most potent but most false myths of our time. If you look at every sector—energy, food, health, the media—the unregulated market has produced monopolies; these sectors are dominated by three or four major companies. The idea that neoliberalism equals real competition and a real market is patently false.

Neoliberalism isn’t the market versus the state. The state has always acted as the guarantor of Capital.

Then on the other hand, innovation: several reports have recently shown that it’s the state that has been responsible for facilitating innovation. Think about Google: Google has been innovative in its time (it’s become less so—getting more repetitive and conservative) but it was helped massively by public funds, by public support.

One has to distinguish between a real market and the anti-market. Fernando Braudel made a distinction between market forces and anti-market forces. It’s the corporations that are the anti-market forces. Small businesses competing with each other can produce a real market mechanism, but that needs protecting—often protecting by the state.

To have a ‘real’ market—a genuinely social market, a market that’s a benefit to everybody—requires, paradoxically but truly, some kind of socialized framework. Imagine a very innovative, competitive system based on cooperatives, in which the workers, their skills and capacities—a true force of innovation—are able to flourish and be realized. That requires public support.

Listeners probably know through their own experiences: any small enterprise that’s innovative very quickly gets taken over by corporations desperate for innovation. Corporations are completely parasitic on small, creative enterprises. It’s everywhere you look. I live near a Tesco, which is a very conservative un-innovative retail store a bit like Walmart; they’ve recently taken over a very cool, innovative coffee shop started, in a way just for fun, by a small group of individuals. When a corporation takes over innovative little companies, it gives them money but it basically crushes their innovative capacity.

CM: You made a really great point about how most innovation seems to be coming from the state nowadays. We’ll have Mariana Mozzucato on next week to talk about her book The Entrepreneurial State, about this myth of Apple being started in a garage somewhere. We have commercials on TV about all these innovations, whether it’s Dell or Overstock.com or whatever, how they’re started in people’s basements, dorm rooms, garages. All that is a myth.

But what’s more of a threat to capitalism and democracy: socialism or neoliberalism? It sounds like what you’re saying is that far more of a threat to what we see as American capitalism and what we see as American democracy is neoliberalism, hardly socialism.

HW: Yes. Corporations have occupied the state. They’ve taken over state departments, ensured contracts. There’s been an effective privatization, a hollowing-out of the state, of democracy. Corporations have served to weaken the power of parliaments, the legislature and ‘elected’ politicians.

An example in Britain is the Health Service. It was, in a way, a form of socialism. It was taking health out of the market. It was saying that health is too important, too fundamental a need to be allocated according to market principles, according to whether or not you can pay. So in Britain people have healthcare as a right, as part of being a citizen. But this is now being dramatically eroded. All the opinion polls say that people still want healthcare to be publicly delivered and publicly provided for. And yet what’s happened is a process of privatization driven by corporations that have been invited into government and have steadily taken over the Health Service. That’s a very clear example of how it’s been corporate power, not socialism, that has threatened democracy.

CM: Last week one of our Irregular Correspondents, Nicole Aschoff, said the U.S. isn’t quite neoliberal, because of examples [of state intervention] like quantitative easing. In your opinion, how neoliberal is the U.S.? And neoliberal or not, how has neoliberalism as an ideology affected the U.S.?

HW: I think the fact of quantitative easing doesn’t weaken the argument that it’s neoliberal. I think it points to the contradictions and inconsistencies within neoliberalism. The claims of neoliberalism are that it’s about a small state, about weakening the state. But in reality, neoliberalism and market capitalism have always been dependent on the state. This is the irony of the situation.

You can look at the example of Thatcher: she used highly-expanded aspects of the state. She weakened the democratic institutions of the state, but she strengthened those dimensions of the state which guaranteed the position of Capital.

The state has always acted as the guarantor of Capital. You saw that in the bailouts, of which quantitative easing is, in effect, a part. There the state moved in—not to support the people, get the economy going, create demand, and create jobs, but to bail out the banks. So the state is part of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism isn’t the market versus the state.

If we understand the complexity of mechanisms by which neoliberalism maintains its power, we have to hit at many different levels that are not necessarily political, but nevertheless are instruments of power.

CM: Let’s talk a little bit about the influence and the impact of neoliberalism. You write how the central relationships that define the state—between state and economy, state and civil society, government and the people—have changed beyond recognition. The processes producing this shift include the steady but radical decline of party democracy and the increasing occupation of the state by private business. To what extent, then, is private business an unchecked branch of government?

HW: I don’t know whether it’s right to talk about a “branch of government.” I think it’s more complex than that. But I’d say that neoliberal governments have created alliances with private business, created an alignment between private business and the interests of political power.

You saw this very clearly with [Rupert] Murdoch. What came out in the inquiries into Murdoch was the number of times he’d been invited to Number 10, the office of the Prime Minister. That was not about Murdoch becoming a “branch” of government, but becoming an ally of government. It’s not that [private businesses] have become part of government. They’re working within their sphere, in this case the media, in ways that are aligned with the interests of the elite that govern the state.

It’s interesting to note that one sees the notion of networks as part of government. We talk about networks in terms of our social movements. But we’re talking about a democratic process—they’re talking about a network that reinforces elite power. Maybe that’s not entirely new; we’ve had C. Wright Mills talking about the Military-Industrial Complex. But that had specifically to do with the alliance between the state and military producers, arms companies. Now we’re in a more complex, widespread alliance between government and private corporations.

CM: You write: “It is not sufficient to show the irrationality and injustice of capitalism, implying the need for a rational alternative. Capitalism is not a monster that can be slain by a single strategic sword. Rather we face a complex and constantly mobile organism: half-machine, with its automatic drives towards accumulation; half-animal, with the reflexes to get around barriers, cannibalize other capacities, and reproduce itself by feeding rapaciously off its environment. We need to recognize we are up against a Hydra-headed system that cannot be destroyed at any one point but can only be surpassed through multiple points of transformation based on an ecology that has at its center the drive for human well-being.”

So if not showing “the irrationality and injustice of capitalism, implying the need for a rational alternative,” then what should social movements be doing?

HW: If we understand the complexity of mechanisms by which neoliberalism maintains its power, we have to hit at many different levels that are not necessarily political in the sense of “run by the state,” but nevertheless are instruments of power.

One good example that has emerged in Britain, and maybe in the States too, is experimenting around alternative currencies, ways of developing a local economy so we’re less complicit. Money and our means of daily life goes into small or social cooperative businesses, and we achieve a kind of autonomy, material autonomy, from corporations. It can’t be complete; none of these local initiatives, these alternatives, are complete in themselves—but this is why I talk about an “ecology.”

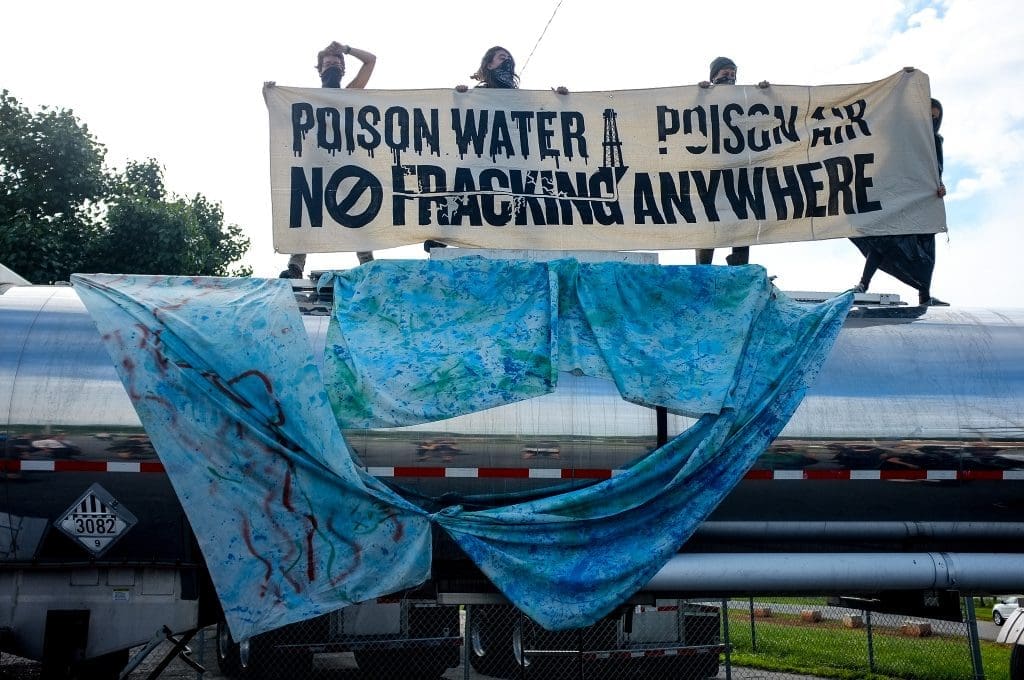

In some ways Occupy, the Indignados, other new movements (although there are connections between them and the ethos of the movements in the ‘60s and ‘70s) start from a recognition of the way that we reproduce capitalism in our daily lives without necessarily wanting to, and that we need to think of ways of breaking that reproduction and turning that daily power into a transformative power, whether it’s through different ways of ‘consuming,’ different currencies, producing renewables, or producing organic food. Being mindful of our daily decisions, thinking all the time: are there alternatives, can we create alternatives? We can hollow out capitalism in the way that capitalism has been hollowing out the state. But that should go alongside the constant process of exposing and making transparent the workings of corporate and state power.

CM: As you’re pointing out, it’s not just being critical, it’s also taking action and showing some sort of transformation that will be the building blocks, the foundation for something in the future that can challenge the means of power right now.

One last question for you, Hilary, and as it is for all of our guests it’s the Question from Hell: the question we might hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or the audience is going to hate your response. I think this is a pretty simple question, I think that our audience is just going to hate the response. How important is secrecy? How much of a villain to neoliberalism are people like Private Chelsea Manning, people like Edward Snowden and Julian Assange?

HW: We can only interpret the way in which Chelsea Manning is being treated, the way in which Julian Assange is being treated, and the way in which Edward Snowden is being treated, as absolutely brutal—there’s such a determination to destroy them. You have to ask why. It is because transparency, the light of public opinion and public perception is more dangerous to the powers-that-be than anything else. It’s a bit like a laser beam. For them it’s completely deadly.

So they’re turning it back on the people that are trying to direct that laser beam on them and they’re trying to effectively kill their capacities by repression and by attempts to isolate them, as with Assange or Snowden, or attempts to silence them, to instill fear. Those campaigners are among my heroes, and we’ve got to give them all the support we can, because without transparency we’re much less powerful, we’re in a kind of fog. They’ve helped open things up.

Wikileaks has been crucial to the Arab Spring, to so much of what’s been going on because we’ve been able to see the workings of power. And in a way that’s what we’re trying to do with this report on Davos. It’s not as potent as something like Wikileaks, but we hope it can follow in the wake of those bold initiatives and enable people to reflect on what has been revealed by Manning and Assange and Snowden.

Transcribed and printed with the permission of This is Hell! Radio. Archived audio to be made available online eventually.