Exploring the potential and the limits of anarchism: a long bike ride to Athens

Everything in Exarchia gets lent and borrowed, everything gets traded. Above all perhaps the most valuable asset: time.

by Antidote’s Laurent Moeri

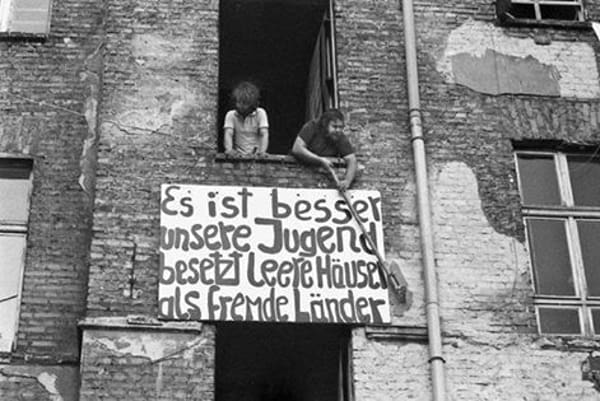

2011 was the year of Occupations. From Cairo, through Athens, to New York, Frankfurt and Zürich, people grabbed their tents and made themselves some space to voice their grievances. But not only that—they established free spaces in which, away from commercialized party politics, they reclaimed the empty husk of democracy and began filling it with life again.

At first glance, the uprisings against dictatorship in North Africa and the waves of protest through Western metropoles didn’t appear to have much in common. Yet they were unified in their impulse to break out of coercive, repressive structures.

Anarchists and Autonomists are often portrayed as deranged rioters. What is often forgotten is the radical political philosophy that underpins their activities: the idea that people are capable of organizing themselves, among themselves and without hierarchies. It is this insight that connects the social movements of the Global North and the liberation struggles of the Global South.

Because democracy does not consist merely of putting a slip of paper in a box every couple of years, but rather of people’s direct say in decisions that have lasting impact on their lives, anarchism is becoming the progressive dream of the 21st century. So in order to get to know this idea, its potential, and its limits a little better, I pedaled down to Athens. During an earlier visit to that city, an anarchist friend had told me she didn’t know whether a utopia would emerge in Athens, but that if one were to appear on the horizon you’d be able to see it from there too.

Starting out in Zürich, going by countless run-over animals and never-ending monocultures, I came eventually to Venice, and then on to Trieste. In northern Italy the Eurocrisis was already evident, and a frequent topic of conversation. I found the parmesan cheese to be particularly emblematic: in all the supermarkets it was locked up in alarm-secured cases.

Then on down the Croatian coast to Opuzen. Opuzen would be unremarkable, had a certain Stjepan Filipovic not been born there. As the commander of a group of partisan fighters, he was hanged by the Nazis at age 26. The photograph of him standing on the scaffold, the noose around his neck but his fists raised high, shot around the world and is hanging in the United Nations headquarters. He shouted “Death to fascism! Liberty to the people!” before he dropped.

His memorial monument was blown up by Croatian nationalists during the Balkan War and, like hundreds of other antifascist monuments in the region, it has been defaced with swastikas and nationalist slogans.

Then through Montenegro and warm-hearted Albania—I arrived in Athens on the 4th of December. The megalopolis that knows neither sleep nor regulated traffic harbors at its very center one of the most extraordinary neighborhoods in all Europe. The mythology of this Rebel’s Quarter began with the student uprising against the military junta in November 1973. Radiating from its focal point, Athens Polytechnic University, Exarchia emerged.

Exarchia again made international headlines in December 2008. After the murder of 15-year-old Alexis Grigoropolous by two policemen there, Athens—and in short order all of Greece—descended into unrest as had never been seen before. The December Revolt, as it is called, was a turning point in modern Greek history, and neither Exarchia nor Athens—nor Greece—can be properly understood without it. Since then, Exarchia has become a laboratory for social movements seeking to put their theories into practice.

But Exarchia is not at all the only area that has undergone fundamental transformation since 2008. All over Greece, neighborhood assemblies have emerged, with one basic tenet: whoever lives here should be able to participate and contribute.

Aided in part by the failure of state institutions, groundbreaking projects for a new, solidary economy began to spring out of these assemblies. These projects are as essential as they are (so far) insufficient. And they have shown that the crisis has not only created misery—in the form of glaring unemployment, homelessness, and vertiginous suicide rates—but it has also presented a chance to fill the ratty shoes of a dilapidated state structure with human feet.

While the neo-Nazis of Golden Dawn hold their populist demonstrations on Syntagma Square and operate a soup kitchen for Greeks only, anarchists a stone’s throw away—but away from all the cameras—are at work in a free clinic. Every day, a variety of medical services are provided free of charge in the basement of a squatted apartment building. The clinic is run by volunteers. Some of the doctors are unemployed, others come in on their days off. Anyone and everyone is treated.

Across the street, there is a cafe that uses all its proceeds to benefit political prisoners. A couple of streets down, a parking lot has been turned into a park and playground. Countless collectives run community kitchens. Classes are offered for Greeks and migrants alike. No one is turned away, everyone is welcome. A free store operates on only donations and is near to bursting with items for the taking. Everything in Exarchia gets lent and borrowed, everything gets traded. Above all perhaps the most valuable asset: time.

The unemployed lose their jobs, but not their abilities. A project called the Timebank is based on this simple principle. People from all careers meet here and trade their time. In this way, a plumber can continue his work in spite of being “jobless,” and receive for each hour of work a coupon of sorts, which he can then “spend” on some other service. Each neighborhood runs its own Timebank. The one in Exarchia currently offers more than 170 services. Carpenters, barbers and translators, even psychotherapists all exchange their capabilities there.

Solidary living is something that must be learned, of course. Therein lies the current limit of our social movements. Acting beyond the promise of monetary reward takes practice. A look at Exarchia reveals that the erection of alternative structures is arduous, but possible—and that with the help of well-organized societal bonds, each can find her own way out of crippling unemployment, out of despair, out of this crisis.

This article was first published in the February 2014 Special Issue of ADC’s Cicero magazine. The original German can be read here.

Translated by Antidote