Transcribed from This is Hell! Radio’s 6 September 2014 episode and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

“We face a state that treats black people as if we are about to rise up in an insurgency at any moment. They preemptively police us as if we are an insurgency.”

Chuck Mertz: Live with us right now, executive editor of the Black Agenda Report, Glen Ford. Good morning, Glen.

Glen Ford: Good morning. Good to be here.

CM: Isn’t it great, this post-racial America? It looks great in Ferguson, Missouri!

GF: Oh, I’m just aglow. I’m bathed in it. Aren’t we all?

CM: Back on August 3rd, we spoke with Jonathan Simon, author of Mass Incarceration on Trial: a Remarkable Court Decision and the Future of Prisons in America. He was talking about the historic cases that led to Brown v. Plata in which the state of California conceded that deficiencies in prison medical care violated prisoners’ Eighth Amendment rights, and how the decision eventually forced California to cut their prison population to 137.5% of capacity, down from nearly 200%.

Jonathan writes, “California built prisons heedless of the humanity of those it planned to incarcerate, recklessly accumulated people with chronic illnesses in those prisons, and committed itself to an extreme penal philosophy that left the state unable to address the inevitable suffering and death. The results were atrocious enough to move even a Supreme Court long tolerant of mass incarceration. In the words of Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion in Brown: ‘Just as a prisoner may starve if not fed, he or she may suffer or die if not provided adequate health care. A prison that deprives prisoners of basic sustenance, including adequate medical care, is incompatible with the concept of human dignity and has no place in civilized society.’”

How much is the policy of mass incarceration in the U.S., particularly in black America, responsible for the shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri?

GF: Shootings like Michael Brown’s, and hundreds across the country every year, are a reflection of the mass black incarceration state—that’s the term that we’re using at Black Agenda Report. The mass black incarceration state began to be put in place in the 1970s as a direct reaction to the Black Freedom Movement of the sixties, which was treated as if it were an insurgency. The mass black incarceration state is a counter-insurgency apparatus, which after more than four decades has created what Michelle Alexander famously calls the New Jim Crow, which criminalizes blacks as a people.

If we don’t see Michael Brown’s shooting and all the others in that context, all we do is pick around the edges. We’ve seen all of this national attention on Ferguson, Missouri, and there is a tendency—and it’s not just the corporate media; it comes from elements of the black misleadership class—to particularize Ferguson, to say that it stems from the fact that Ferguson is a two-thirds black city that has only a handful of black police and only one black city councilperson, and so what Ferguson needs is more black elected officials and more black cops.

But right down the street is St. Louis—which until very recently was a majority black city, had a black mayor, had a black police chief (who’s now been appointed to be the public safety director for the whole state of Missouri)—as people were protesting Michael Brown’s murder in the street, the police in St. Louis murdered another black person. We have had black mayors and heavily black police forces for the last thirty or forty years. And yet they still shoot us down in the streets.

In Washington, D.C., we have a police force that has a higher ratio of black folks than the population at large. I guess we’re overrepresented! And they still shoot you down in the street. In Atlanta, the ratio is almost a perfect match for population and police. And they still shoot you down in the street.

So this mass black incarceration state’s manifestation on the ground is dead bodies at high noon.

CM: That is incredibly frightening. One of the things that we were talking about with Greg Palast the other day was how when there is a mass shooting, you will always see the politicians come out and start talking about gun control, but nothing ever seems to be done.

Is the way that gun control is the political reaction to a mass shooting the same as when we hear people saying we should reform the police forces whenever a white police officer shoots an unarmed black man? Is that always the response? If we can just reform the police department, get more blacks in the police department, then the problem will be solved?

GF: Yeah, that’s always the response. And with the Congressional Black Caucus it’s even more hypocritical and dishonest than that. Back in June, a white, somewhat liberal congressman named [Alan] Grayson introduced an amendment that would defund the Pentagon’s 1033 program. That’s the program that sends billions of dollars in militarized weapons and gear and training to local police forces—the very thing that there seems to be a consensus is a bad thing.

The amendment failed miserably. And 27 of the 40 voting members of the Congressional Black Caucus voted against it. Including the congressman from St. Louis, William Lacy Clay, who represents Ferguson. Only eight members of the Congressional Black Caucus voted for it.

But now they’re all gathering for their September galas, and you’re going to hear them all talking about what a terrible thing it is that we have militarized police forces. They funded it. So they lie when they say that they don’t have anything to do with this. In 1986, half of the Congressional Black Caucus, voted for the 100:1 ratio on penalties for crack cocaine. None of them admit to that today. But they are part and parcel of this.

And as for black police chiefs and mayors: Newark, New Jersey has had a black mayor since 1970. Ken Gibson’s campaign was conceived and run on my mother’s kitchen table. And yet, black folks are shot down like dogs every day, to this day, in Newark.

We face a state that treats black people as if we are about to rise up in an insurgency at any moment. They preemptively police us as if we are an insurgency. We had COINTELPRO in the sixties and seventies—and didn’t learn about it until the Church Committee in the mid-seventies—but they had the COINTELPRO program which went after the leadership. That’s when we saw the murder and imprisonment of leaders who were thought to be too militant. But the mass black incarceration state treats all black people as public enemies.

It manifests itself in the biggest prison population in the world. Black Americans make up 0.6% of the world’s population, but about 12% of the world’s population of prison inmates. That it grotesque. That is unique on the planet, and cannot be anything but a manifestation of an ongoing, long term U.S. policy to treat black people as if they are, by nature and definition, criminals. Or insurgents. And that’s more to the point.

“With Ferguson, we’re starting to hear the old slogans and the old ways of reasoning resurfacing as if they are new. And to two generations, they are new.”

It is very clear that black people as a group recoil against the effects of this mass incarceration state. Every rebellion since the 1935 Harlem rebellion (which was the first urban revolt that people called a ‘race riot’ which was not riots of white people against black people)—every single one of those revolts stems from a police atrocity or the perception of a police atrocity. Black people will respond to these atrocities.

Our problem is a contradiction in our community. I’ll encapsulate it by saying this: there are two currents in black America, and these currents have existed as long as there has been a “Black America.”

There is the self-determinationist current that says that black folks have a right to protect ourselves, to build our own communities, to make decisions that we think are best for our people, regardless of what other people say—and so on, all of what self-determination means.

Right alongside it—living in the same black brain—is the representationist current that says black folks have the right to hold all the positions that everybody else in America has; to be the president, the generals, and even the biggest gangsters in the United States.

For a certain current of black politics, the representation—that is, seeing black faces in high places no matter what they’re doing—is what represents progress. But for others, self-determination—the accumulation of black power to run our own lives and defend ourselves against things like the mass black incarceration state—is what politics is supposed to be about.

As I said, they coexist almost always in the same head. So it is a question of leadership. With COINTELPRO at the end of the sixties, the radical black leadership was decimated. A new leadership was launched, through the new opportunities that the victories of the sixties made possible. [These new leaders] went straight into electoral politics and into the corporate arena. They made a pact with the Democratic Party and became embedded in it. And all of that mitigates against mass grassroots activity. We see where it leads. It leads to a Congressional Black Caucus that votes to militarize the police that shoot down their constituents in the street.

CM: When we were talking with Jonathan Simon about mass incarceration, he said it might be ending. Without the political will to end mass incarceration, instead it’s ending with budget deficits, or because of court decisions—

GF: I just interviewed a person from the Sentencing Project. They just completed a study. And they take note of the fact that in recent years, every year, prison populations have decreased. But they also take note of the fact that it’s very slow. At this rate, the prison population would not return to 1980 levels for 87 years. So that’s not something for me and you, or even for our grandchildren.

CM: I’m still heartened by the idea that mass incarceration might be ending because of court cases or because of the bottom line, but I get really disenchanted when I think it’s not because of political will. It’s not because people want to end mass incarceration.

It reminds me of the interview we did with Alice Goffman. when she—in her book she writes about living in the Sixth Street area of Philadelphia and how it’s like living under an occupation. Is this all an attempt to control the population? Is that what mass incarceration is all about?

GF: Of course it’s an armed occupation. This is nothing new. We all said that in the sixties. We said it every day. And this is before the transfer of billions and billions of dollars in military gear. It is not the military gear that gives the police-black community relationship an occupation characteristic. [The police] were an occupation army before they looked like they came out of Fallujah or Gaza. They were an occupation in soft blue caps with revolvers instead of machine guns. It’s incidental what kind of gear they wear. It’s their relationship to the people.

They have been an occupation army—and a conscious one—for five decades. Even this Sentencing Project—which is a liberal organization, not a radical organization with radical analysis—their conclusion [about the mass black incarceration state] is that it emerges from white people perceiving black people as the cause of crime. That is, they would not have created this barbaric edifice unless they intended to put black people in it.

CM: Isn’t this strategy “working,” as far as the police are concerned? We always hear that right now crime levels are at all-time lows, according to the FBI.

GF: It’s never been predicated on crime. Crime levels go up and down. Nothing changes unless the relationship of power in this country changes, until black people can get enough power to stop white folks and their government from doing what they clearly want to do, which is throw as many black people in jail as possible.

We have constitution-free zones all across this country, and they coincide exactly with areas of black inhabitation. Zones in which the Bill of Rights is not in effect. And the uniformity of it, the speed with which, after 1970, this mass-incarceration regime spread north, east, south and west leads one inevitably to the conclusion that this is a general white response to the black presence in this country. It is a response to the period in which black folks said, “we’re not staying in what you call ‘our place’ anymore.” The response was, “okay, well, we got another place for you. That place is prison.”

“There really is no choice but to organize a politics that is not just outside the Democratic Party—that is an absolute necessity—but one that is consciously resistant to the mass black incarceration state. And it must be done in a confrontation with the coercive powers of the state. That is, the police. And it’s got to be a head-on and very conscious collision with Wall Street, which benefits from it all.”

CM: Speaking of trying to control a segment of the population, let’s talk War on Drugs and Richard Nixon for a second.

This is from Nixon advisor H. R. Haldeman’s diary: “President Nixon emphasized that you have to face the fact that the whole problem is really the blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognizes this without appearing to.”

And then there’s this from Nixon White House Counsel Ehrlichman: “Look, we understand we couldn’t make it illegal to be young or poor or black in the United States, but we could criminalize their common pleasure. We understood that drugs were not the health problem we were making them out to be, but it was such a perfect issue that we couldn’t resist it.”

I want to make certain everyone understands that I do not think drugs played a role in Michael Brown’s death directly, but Glen, how much did the War on Drugs—and the culture and infrastructure it created—play a role in Michael Brown’s death?

GF: The release of those tapes was wonderful. They allowed us to become, after the fact, witnesses to the great conspiracy. Their actual words, the actual script, is far more fear-inducing than any speculation or political novel that you or I could write.

They fashioned the War on Drugs as a cover, a subterfuge, for the war on black folks. This was a white (frankly) cover for treating all black people as a criminal class, and a device for not just imprisoning as many as possible but smearing the name of black people. Of making crime and drugs and immorality and debasement and the loss of civilization—all of it—synonymous with black people.

Clearly they succeeded. And frankly, they succeeded so well because there was a white population that was ready to hear it. It was made ready, of course, by slavery.

CM: You write, “the usual black preacher-politicians—first responders to threats to domestic order—hector that the cures to what ails Ferguson are readily at hand: the Gospel and the vote. But liberation theology has given way to prosperity, hustling, and psalm-flavored ghetto pacification while electoral politics, as prescribed by the black misleadership class, is a euphemism for induction into the Democratic Party, which has encaged black politics for roughly the same period as the mass black incarceration state has encaged black bodies in the world’s largest gulag.”

Let’s unpack that a bit. “Liberation theology has given way to prosperity, hustling and psalm-flavored ghetto pacification.” Have you seen any signs that that black religious leadership might be changing their focus back towards the kind of social justice that the black leadership class had back in 1960?

GF: I don’t see any resurgence of black liberation theology in this country. This new black misleadership class—that was unshackled by the civil rights victories of the sixties—just went into the Democratic Party. And that’s where our movement died.

Many of these folks weren’t just rank-and-file hustlers and opportunists, they were high-ranking members of what we used to call the Civil Rights Movement. I’m talking about Jesse Jackson, who went corporate as soon as Dr. King’s blood was dry.

We saw a mass march of the so-called black leadership into the Democratic Party, and they began preaching that we had to have a more sophisticated movement, that the movement had to travel from the streets to the suites. What that did was suppress grassroots activity. Whether it’s a black politician or a brown or a white politician, a politician does not want an active, everyday, 24/7 movement in his community. It is an irritation, a nuisance at best—and at worst a mortal danger to him keeping office.

Politicians only want you to come out once: mass activity every two or four years, to vote for him. So we’ve seen over these four or five decades the accumulated effects of the suppression of black grassroots politics in the United States.

Almost all of black politics takes place, by now, within the Democratic Party. And the Democratic Party is, of course, one of the two business-capitalist parties in the country. The Democratic Party is not going to let folks advance within its ranks who represent any kind of real threat to the prevailing order. So our politics are in lockdown. They have been for four or five decades.

There really is no choice but to organize a politics that is not just outside the Democratic Party—that is an absolute necessity—but one that is consciously resistant to this mass black incarceration state. Mass black incarceration effects every aspect of black life. Employment, health, housing, everything. It is that pervasive.

At Black Agenda Report we believe that the two biggest challenges to black America are mass black incarceration and gentrification.

Gentrification because it closes the window on our ability to form dense enough population centers—majorities in cities—to organize. Not just in the electoral system but in a grassroots way, it’s hard to organize people who have been dispersed. We see that the Chocolate City is becoming a thing of the past. St. Louis used to be one. It’s not anymore. Washington: not any more.

So if these are the two biggest challenges facing black America, the only hope, the only reason to become involved in electoral politics is to oppose those challenges, to defend ourselves against those challenges. It can’t be done through the Democratic Party. It must be done in a confrontation with the coercive powers of the state. That is, the police. And it’s got to be a head-on and very conscious collision with Wall Street, which benefits from it all.

That’s a whole different politics. And it’s only just begun—if it has begun yet—in black America.

CM: Glen, I’ve got one last question for you. As always, it’s the Question from Hell: the question we might hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate the response. There are a lot of Democrats out there who are excited about Hillary Clinton becoming the next president of the United States because they believe that that could help women politically in this country…

Are African Americans better off now that they have had a black president?

GF: We are only better off in that we know we will not be better off with a black president. It took the experience of people feeling it so painfully to understand that truth. That’s a rite of passage that nobody wants to go through. The depression—the hangover, I call it—will be as deep when Obama leaves as the euphoria and delirium was high [when he was elected]. But that’s what happens when you go to Mardi Gras.

CM: Thank you so much for being on the show with us this morning, Glen, it’s always great to hear your voice.

GF: Alright! Bye, bye.

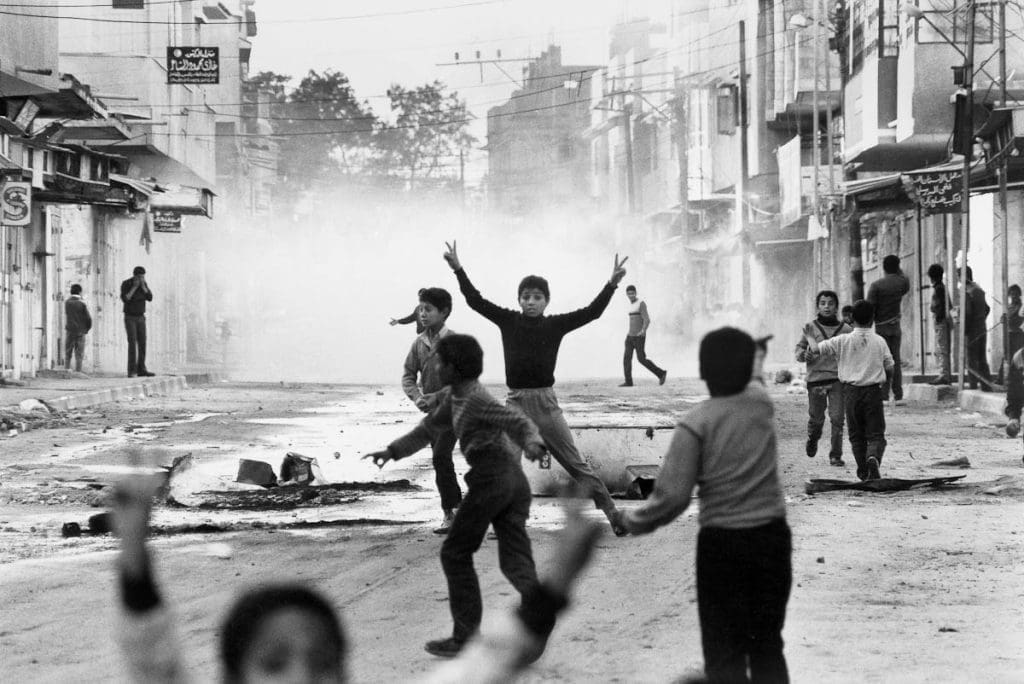

Featured image: the First Palestinian Intifada by photojournalist Jean-Claude Coutausse