Transcribed from the 11 October 2014 episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the full interview:

“The level of brainwashing in America doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world.”

Chuck Mertz: Arundhati Roy is the author of Capitalism: A Ghost Story. The way Arundhati tells it, “capitalism has been a tale of horror for millions of people in India and tens of millions of people around the world. For many, capitalism is not a theory or an idea, but a frightening reality that tears apart their lives every day, and it’s getting worse.”

Good morning, Arundhati.

Arundhati Roy: Good morning.

CM: The name of your book is Capitalism: A Ghost Story, but could we also call democracy a ghost story at this point? How much do you think the wars in the Middle East that the United States has been behind—the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan, the invasion and occupation of Iraq, the bombing in Pakistan—how much do you think this undermines the ‘brand’ of democracy?

AR: The trouble is that we are reduced to having to accept that a ‘brand’ is all it is. It is a product. There was a time when democracy was a real ‘threat.’ Democratic regimes—in Iran, in so many countries in Latin America—were toppled because they were real democracies. Chile. We know that history.

Then it was taken into the workshop for some touching up, and came out as this product which was fused with free market capitalism. And then the wars start being fought to install these new kinds of ‘democracies.’

In India, elections are celebrated every five years, and everybody is told, “look at this great democracy.” But it is a democracy for only a few people. For the rest it has been something else entirely. For example, since 1947 (when British colonialism ended and another kind of colonialism began) there has not been a single year when the Indian army has not been deployed against “its own people” within the borders of India. Not a single year.

Kashmir. Manipur. Nagaland. Punjab. Hyderabad. Now the army—I mean the paramilitary—is surrounding the forests of central India making war against the poorest of the poor because they happen to live where there is a huge wealth of minerals. The agreements have already been signed. History is repeating itself.

India wants to be a player in the big leagues, and because it does not have colonies, it colonizes its own poor.

CM: I am starting to wonder if there is a sustainable version of humane capitalism, especially after reading your book. When you consider the millions displaced, land lost to huge infrastructure projects or privatization or, as in India, farmers moved off their land: hundreds of thousands commit suicide; they move into the city to find no hope, no jobs; they find racism, they find hatred; they move back to their villages which are gone; they fight to get their land back that was taken by corporate paramilitaries; and they are called terrorists for doing so.

Is there a humane capitalism, and we’ve just chosen the not-so-humane kind?

AR: Unfortunately, I don’t think so. I think it’s time we faced up to the centrifugal force that this system creates. What can it do except increase the gap between the rich and the poor? What can it do except arm the rich to attack the poor?

In India now there are a hundred people who own more wealth than 25% of the GDP, and there are 800 million people living on a few cents a day.

And there are laws under which even thinking an anti-government thought is a criminal offense.

And then there is the Armed Forces Special Powers Act, under which non-commissioned officers can kill—soldiers can kill—on suspicion. Inside the borders of the country, and not in a situation of war. All they have to do is declare they were disturbed. Wherever the army is deployed this is going on.

And there are thousands of people in jail right now. There are thousands of people dying in police custody.

And now, of course, we have a new government, with a prime minister who in 2002 presided over a pogrom against Muslims in Gujarat in which 2,000 were killed. Women were raped and burned alive. And in his campaign for prime minister, when Reuters asked him if he regretted what had happened, he said he would regret even running over a puppy. He refused to apologize. And then he came to Madison Square Garden and spoke about global hygiene to screaming mobs of Indian businessmen shouting “Modi! Modi! Modi!”

This is the reality we live in now. This man is creating an atmosphere of fascism. I mean, he belongs to a cultural organization called RSS, which openly worships Hitler and says things like “the Muslims of India are the Jews of Germany.” There are Muslims living in camps now, having been driven off their farms and lands. And meanwhile he comes to America and tries to fuse himself with Gandhi, saying “I believe in global hygiene.”

CM: So Modi is elected prime minister. The United States had condemned him in the past, associating him with the Nazis and Nazi ideology; then as soon as he gets elected, the United States drops all of those complaints and allows him into the country when he wasn’t allowed in before. What should that reveal to us, either about the United States or about the way that geopolitics is played?

AR: Well look, first of all, your own president is involved in drone attacks and killing people. It’s just that some people are hands-on and some people kill in a remote-controlled way by pressing buttons and looking at computer screens. So I don’t care either way who is allowed in or not. Plenty of killers have been allowed in.

Considering the United States’ own history, from Hiroshima onwards, how can I work myself up over whether yet another person with very dubious reputation is allowed in or not?

“Culture and identity and race are things that affect people’s souls. This is the music, and this is who you are, and what your history is…it cannot just be set aside by class analysis. But then neither can that replace looking at society through the lens of class.”

CM: You are a recorder of the kind of inequality that takes place every day around the world and the harsh conditions of poverty that those on the bottom end of that inequality suffer through every day and throughout their lives. Here in the States, inequality is now only just becoming an issue that our political leadership is willing to exploit. Not that policies have been put in place to stop that inequality, and it continues to grow in the U.S…

To you, as an observer of poverty, as an observer of inequality, what does it say about the U.S. that inequality has been growing since the 1970s and is at it its highest level since 1928, and it has not become a political issue? What does that say about the U.S.? Or what might it say about India, where inequality also doesn’t seem to be addressed as a political issue?

AR: No, in India it is an issue in the sense that there are massive resistance movements, social movements; there are battles, there are guerillas in the forests, there is armed struggle. People are simply being beaten down.

But I think the level of brainwashing here in America doesn’t exist anywhere else in the world. Here, I think there’s been very a careful orchestration; the real battle has been the controlling of minds. The levels of surveillance that Edward Snowden and others have revealed is just the latest and most drastic maneuver involved in controlling people.

In a country like India, the majority of people live “off the grid.” So controlling them through these methods of internet surveillance is not possible because they are not on the internet. It’s not a population that can be controlled by the media—yet. Of course, TV has been making huge inroads.

But here in the U.S., I think the government starts with the understanding that you have to deal with it the way you deal with a war. The more this increases, the more warlike that strategy of what armies call “perception management” will be. Here, perception management is a great art. People accuse Islamists of indoctrinating children, but here, from the time a child opens its eyes it’s being indoctrinated to think that there’s no other way of living, there is no other kind of happiness, there is nothing except consumerism that will satisfy the desire of his soul.

CM: What does the continual return to inequality, despite it proving to be devastating to the economy, say about the nature of capitalism?

A couple of weeks ago we had Slavoj Žižek on the show, and one of the things that he was talking about was the abandonment of the idea of communism. He was pointing out how if somebody wanted to start a communist country, they wouldn’t say, “hey, the Soviets did nothing wrong! We’re going to start right from that place and do it the same way all over again!”

So why do we continue to make the same mistake, over and over and over again, of rising inequality under capitalism?

AR: It’s not a mistake. It’s the nature of the beast. This is not to say that communism and the ways in which it was practiced in the Soviet Union and in China and many other places have not made mistakes.

I’ve written about the system of castes, which is perhaps the most cruel socially hierarchical system that the human imagination has come up with. And unlike racism, this is approved in the scriptures. It has religious sanction. There are a hundred million people who are called “untouchable.” Untouchable not in the Hollywood sense but in the physical sense that these are polluting human beings. And they are one third of the population of the United States.

And you look at how entrenched it has been, and yet the communist movement in India—which was significant—could not address it, did not have the tools. All over the world, the fact is that the politics of culture and identity and race are things that affect people’s souls. This is the music, and this is who you are, and what your history is…it cannot just be set aside by class analysis.

“The mining companies involved in murdering people in the forest can also be running law schools, and in the law schools they have courses on the poetry of resistance. So we are living in a lunatic asylum. At least we must know the boundaries of our cells.”

But then neither can that replace looking at capitalist society or any society through the lens of class. It’s like the heart and the soul is race, identity and culture; and class and political economy is the skeleton; one makes no sense without the other. I think capitalists have to understand that.

Because otherwise, as I write about in Capitalism: A Ghost Story, the major corporate foundations like the Rockefeller and Carnegie and to a great extent the Ford Foundation—they have cultivated an identity politics that removes the whole question of economic injustice. It becomes a firewall against those who question the economic order.

It locks people into these little silos that work as a firewall against any radical questioning. This is a mistake that the Left has to address.

CM: Arundhati, I’ve got one last question for you. It’s what we call the Question from Hell: the question we hate to ask, you might hate the answer, or our audience will hate the response.

You were just talking about corporate foundations. In your book you write about how this is the way that they do colonialism nowadays, they’re the new proxy; corporations are privatized colonialism. And this impacts everything today; it impacts, notably, education here in the U.S.—the economist Dean Baker has been on our show talking about how it’s almost impossible to get an economics paper that is in any way critical of neoliberal politics published at a university, because those foundations fund those economics schools.

You mentioned the Ford Foundation. I was talking to a friend of mine yesterday about this, and he said, “well, the Ford Foundation does fund some really good things; they fund Amy Goodman and Democracy Now! He quoted Michael Moore: “why not take that foundation money? Those people will give us enough rope to hang them.”

Is there anything wrong with taking from these corporate foundations if you then turn around and burn the people who gave you that money?

AR: Well, I’m not talking about some pristine position where you have to be pure. That’s not even possible. Certainly Ford Foundation does fund some very, very good stuff, and I’m not saying nobody should take money from them. I’m just talking about understanding the whole operation. We have to ask, when does the radical edge gradually get sanded down?

If you look at what Ford itself says, in its own description of what it sees itself as having set out to do, it talks about being an organization to defeat communism and to further the interests of the United States. You have to look at the history of what it was doing, let’s say, in Indonesia. We all saw The Act of Killing. What was the Ford Foundation doing at that time? What was the Ford Foundation doing in India?

I’m not a pristine person. But we have to understand the game, because we’re all playing in it. And how do we deal with it? How do we respond to—for example, in India—the big mining corporations that are the reason for the wars and the massacres going on in central India? They fund literary festivals where people come and talk about free speech. They have the money to play both sides.

How do we talk about limiting the power of these people? How do we respond to clear conflicts of interest? Take the big corporation, Reliance, in India: not only does it own petrochemicals and mining and textiles and internet and universities and schools, it also owns twenty-seven 24-hour news channels.

The mining companies who are involved in murdering people in the forest can also be running law schools, and in the law schools they have courses on the poetry of resistance.

So we are living in a lunatic asylum. At least we must know the boundaries of our cells.

CM: Arundhati, I really appreciate you being on the show with us this morning. Truly an honor and a pleasure. Enjoy the rest of your weekend in New York.

AR: Thanks, then. Bye!

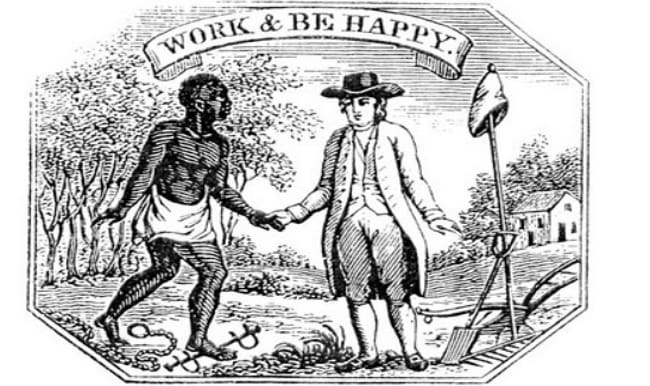

Featured image credit: Nagara Gopal