by Fatty McDirty of Lower Class Magazine

(deutsche Originalversion hier einzusehen)

The new year has begun with the sad certainty that the far Right is in full sail. In Germany, racism, xenophobia, and nationalist sentiment are seeing a once-in-a-generation boom.

Surveys are showing that around 50% of respondents sympathize with or at least “understand” the current wave of xenophobic demonstrations. Agreement with statements such as “I am worried that radical Islam is becoming more significant in Germany” and “Germany is currently taking in too many refugees” is polling even higher than that.

The new year has begun with another sad certainty: that this trend will probably not be reversed in the short term. War and crisis abroad are driving more and more people to flee, often to Europe—while a strong Left that could counter reactionary sentiments at home is not in evidence in very many EU countries. The strengthening of terroristic jihadi movements in geopolitically crucial regions is fanning the flames of islamophobic, racist, and chauvinistic ideas in Europe’s metropoles, both inside and outside established bourgeois political parties. Meanwhile the idea of an independent Left appears to have been—plainly speaking—pulped. It is time to ask how lost ground can be retaken.

Where Is the Enemy?

We need to learn, once again, to differentiate. Not every racist is a fascist. Not everyone who seeks comfort in the well-being of her “nation” is a fascist. And not every nationalist is a neo-Nazi. We have to know our enemies in order to fight them, and we have to fight them as they are.

Parts of the Antifa movement are fixated on the “classic” neo-Nazi, organized in clubs or in the NPD (National Democratic Party of Germany, successor to the German Reich Party) and appearing in all the ways we are used to. Wherever five of these exemplary characters gather to demand “Germany for Germans,” we will show up to tell them they aren’t welcome.

That’s fine. On the other hand, the everyday chauvinism, racism, and authoritarianism that comes out of the self-anointed political “center” does not receive the same vehement response.

Fascism has many faces. The neoliberal “cultural warrior” variant from the Identitäre[i] movement has a different ideological basis than the variant connected to the National Socialist tradition. The Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party carries fascist water, but it’s incorrect to accuse them of recourse to national socialism as such. That’s not their jam (except with regard to individual members, perhaps).

We have to understand these movements for what each of them is—and not all of them are “Nazis.” Better differentiation will guard against an inflationary use of the term “Nazi,” and—even more importantly—against missing an enemy because our radar screens are too small.

The radical Left’s selective blindness appears even graver when it comes to the relation of fascism to the German state. Even state and law enforcement support of neo-Nazi murderers in the NSU (National Socialist Underground) has not prompted any radical Left campaign appropriate to the task.

And the issue of support of Banderist[ii] and neo-Nazi militias in Ukraine, which is openly practiced by every bourgeois political party of the German Federal Republic, has barely been broached.

An antifascism staring daggers into every activity unambiguously identifiable as “Nazi” isn’t doing anything wrong—but it is being too well-behaved. An antifascism that balks at attacking capital and the bourgeois state is doomed to remain Sysiphean at best.

Protecting Neoliberalism

“We do not regard antifascism as an end in itself, but as a means to protect bourgeois capitalist society from the monsters it creates,” wrote the No-WKR Federation (which mobilizes resistance to the annual rightwing galas thrown by Viennese academic fraternities[iii]) recently. The sentence is refreshingly honest. It reflects the praxis of broad segments of the antifascist movement which basically act as though nationalism, racism, and the targeting of refugees for discrimination were things that press in on bourgeois-democratic society from outside.

The image of “monsters” is a trip-up as well. It suggests that bourgeois society is a pleasant, friendly mother who has, clearly through no fault of her own, brought up an ugly, mean, and aggressive child that has now inexplicably turned on her—its own poor mother! The horror!

The brave antifascist runs to the rescue! It goes unnoticed that nationalism, racism, repression, the walling off of our metropoles, subjugation, exploitation, and war are not things to which bourgeois society needs to be forcibly compelled, least of all by fascists. These things are already at the core of bourgeois society’s operation. The No-WKR Federation’s theory of fascism, thankfully but regrettably, makes explicit what parts of the antifascist movement already thoughtlessly assume.

Right now, since straight-up fascists can surely be found demonstrating somewhere, further contradictions seem to have escaped our attention as well; parts of the autonomous Antifa are exerting themselves to establish a “broad coalition across civil society” that spans from Left parties through union functionaries and Greens all the way to Social Democrats (SPD)—even including, as of recently, some camps within the ruling CDU (Christian Democratic Union).

This kind of approach was called the “Popular Front Strategy” (Volksfrontstrategie) in earlier times, and was regarded as the correct approach by communist parties resisting fascist regimes. The reasoning behind it (as formulated by one of the strategy’s founders, Georgi Dimitrov, a Bulgarian theorist of capitalism and longtime Comintern functionary under Stalin) was that fascism, where it takes hold, is “not simply the replacement of one bourgeois government with another, but the dissolution of class-based bourgeois state power—bourgeois democracy—by an openly terroristic dictatorship. To ignore this difference is a serious mistake.” It follows, then, that in this scenario the workers’ movement is no longer in a position to engage in revolutionary struggle but only in a struggle “between bourgeois democracy and fascism.”

Therefore, Dimitrov concludes, one must struggle alongside all bourgeois forces—conservative, liberal, and left—that stand opposed to fascism, and struggle not (yet) for socialism but rather for the reinstatement of democratic relations and institutions.

This strategy has had its problems, historically—above all when, after the victory over fascism in the Second World War, Soviet prerogatives were subordinated to other Allies’ imperialist imperatives, leading (among other things) to the destruction of large and locally well-regarded revolutionary movements in Greece and Italy.

Important to us today, however, is to recognize this as a strategy against fascism in power and not against fascist movements within bourgeois-democratic imperialist states. Nonetheless, parts of the antifascist movement are adapting this strategy—without any historical reference or the theory that would come with it—into their day-to-day praxis. They suppose that anywhere fascist demonstrations (or nationalistic ones with fascist elements) occur, we have to work alongside “all the forces of civil society that are also against Nazism” to stop it.

This is also very good manners. It is little more than a self-defeating effort to be compatible with the political requirements of bourgeois-Right parties. “Do not heed their calls!” Chancellor Merkel has implored those perhaps tempted to join the PEGIDA demonstrations in Dresden. For in Germany it is a “matter of course” to aid refugees and to “welcome people who seek refuge with us.”

Pinstripes and Arson

Whoever falls for this chatter is really beyond help. In the 1990s, through the cooperative engagement of literally fire-starting neo-Nazis and pinstripe-suited politicians, the right to asylum in Germany was effectively abolished. Already then, the oh-so-friendly bourgeois society—through its political (CDU/CSU, SPD) and mass media (Springer) representatives—had entered into an informal alliance with “its own monsters.”

“Beneath the ice-sheet of civilization and liberalization that we’ve slowly learned to bear,” wrote historian Ulrich Herbert in retrospect, “it appeared that as always there existed a cesspool of xenophobia and violence, and that it would be easy, given the right opportunity and some help from above, for the ice to break.”

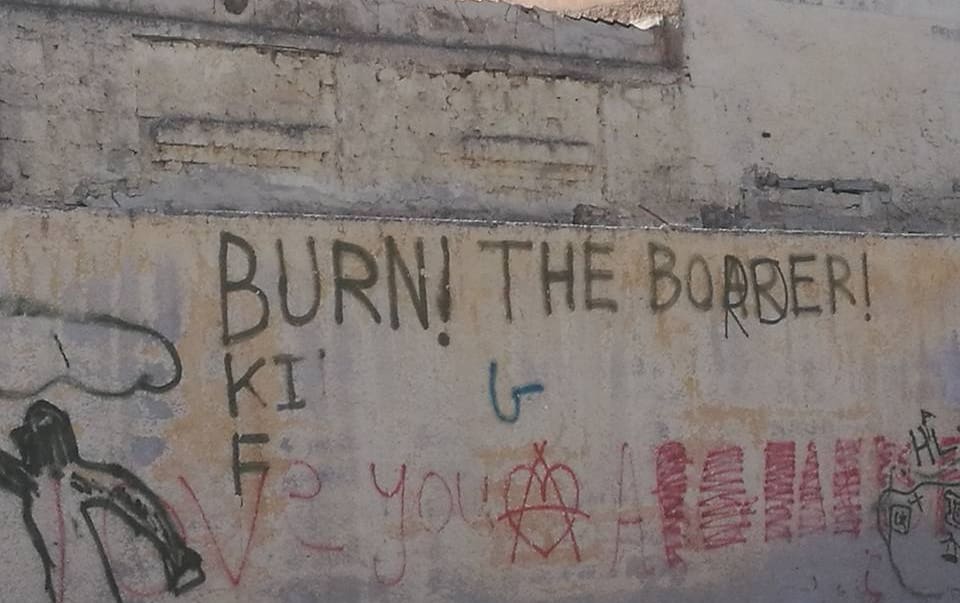

Even if we, unlike Ulrich Herbert, never learned to bear the ice-sheet of civilization and liberalization—to say nothing of whether or not we find the abstract dichotomy of “civilization” here and “barbarism” there particularly apt—a look back at the nineties shows it was the bourgeois state itself that truncated the right of asylum, and in doing so it established a partnership with those who stood in front of asylee group homes with spraycans and wrote, “Germany for Germans! Foreigners Out!”

The fascist mob didn’t have to take power to achieve its goal of effectively closing Germany’s borders to “freeloaders” (as the newspaper Bild so lovingly referred to those in search of aid back then). Bourgeois democracy achieved that all on its own.

This achievement holds to this day. It is not PEGIDA demonstrators who travel to the Greek-Turkish border to save the Homeland from Syrian refugees. It is German police officers. It was not HoGeSa bar-brawlers who passed—again!—newly tightened asylum rules through German parliament, but the Green minister-president of Baden-Württemberg state, Winfried Kretschmann. And it is not the “Nein zum Heim”[iv] parade of assholes that is asserting German interests in the former Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Greece, and Ukraine, but your basic, average Red-Green or Black-Yellow mainstream political coalitions.

Is this to play down the rightwing and fascist movements that are gaining ground every day? No way. We have to fight HoGeSa, and PEGIDA, and whatever the hell the rest of them are called. We simply cannot allow ourselves, in this struggle, to be tricked or forced into overlooking what bourgeois capitalist states are.

Does this mean we should never and under no circumstances enter alliances with bourgeois-democratic parties or institutions? No again. But when this option arises, we do have to assess the concrete situation. Who would such an alliance be helping? Does it help us by politicizing or radicalizing members and supporters of bourgeois political parties like the Greens and Social Democrats, or will we simply function as a figleaf so these parties can pose as representatives of a “humane” and “open” Germany?

The Means Available To Us

The palette of possible antifascist interventions is large and rich in variety. It begins at criticism of the contents of rightwing ideology, continues through the public exposure of specific cadres and functionaries within fascist movements, and stretches all the way to substantial attacks on the various ways these movements manifest themselves in public life.

Which methods we employ should not be decided by our irrational sensitivities but should be guided by the question: how can we most effectively impede—or, ideally, completely prevent—the emergence or strengthening of radical rightwing movements? A method appropriate to a particular purpose will not necessarily be applicable to all others, or at all times. Blockade marches could be the right strategy in one place, whereas in another they could be used jiu-jitsu style by the rightwing movement to bolster their self-identification as victims whose “democratic rights” are being taken away. The firmer the method being used, the more carefully it should be considered.

Blockades, outing/doxxing, and even more militant actions are perfectly legitimate, to be sure. But they all have one thing in common: they are applied where radical rightwing mobilizations are already happening. Even more sensible would be political strategies that don’t even let it get that far. Places with a strong antifascist, radical Left community presence and infrastructure work as a prophylactic against rightwing chicanery. Golden Dawn can’t do its dirty work in Exarchia. Turkish fascists don’t dare enter Okmeydanı. Even in Kreuzberg, where our community presence has long been eroding, we can still declare that nobody who lives there is getting politicized rightward.

In short: in neighborhoods, milieus, and subcultures in which we foster social struggles by building real oppositional structures, we save ourselves the trouble and endless pain of pushing a stone up the hill like that poor mythic hero.

Antifascism as a purely reactive, defensive strategy will not win us any new oppositional territory, as recent years have shown. Without a politics of class and without a real-existing infrastructure, Antifa remains a kind of ineffectual fire department that, because of its own weaknesses, keeps falling back on the mere defense of bourgeois society and its (real or supposed) achievements. Such an Antifa, ironically, becomes “better than federal law enforcement.”

In light of this, we should return our attention to what it is we really want: to fundamentally change the basic assumptions of society and overcome the bourgeois state and capitalism. The antifascist project, to be internally consistent—and to win—must include building up the radical Left, in the most literal sense.

Translated by Antidote

Featured Image: Swiss Antifa focusing its energy on reclaiming the streets in Bern, 2013 (translation: “Occupation not Ownership”). All other images and captions: Lower Class Magazine

+ + + + +

[i] In lieu of an approximate translation of this relatively new political classification on the German Right, we propose a direct English analog—“Identitarian”—because of its parallels in both the British and American (as well as other) contexts.

[ii] Stepan Bandera was a Ukrainian nationalist leader with close but complicated ties to the Nazis during World War II, who is regarded by today’s Ukrainian “patriots” as a national hero.

[iii] Antidote republished a thorough description of these fraternities after the Nazi Balls in Vienna last year.

[iv] “No to the [asylee] Home!” Local movements against the establishment of group homes for refugees—in most cases little more than barracks, and often denounced by their unwilling residents as camps—have sprung up in cities all across Germany. And not out of humanitarian sympathy.