Transcribed from the 13 June 2015 episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the full interview:

“We don’t want to be the alternative in a generalized system of inequality and injustice. We want to be the mainstream.”

Chuck Mertz: A revolution has been happening in Greece that may overflow and create solidarity for all of us. At least that’s the hope of this movement: to have the potential to change the way we lead our everyday lives.

Live in studio, all the way from Greece, Christos Giovanopoulos, is a member of Greece’s SYRIZA party and an activist working with Solidarity For All, a network of grassroots organizations in Greece fighting against austerity. Chris is currently touring the US, speaking to different groups and raising money for Solidarity For All.

Hello, Chris, how are you?

Christos Giovanopoulos: Hi! Yeah, very well.

CM: At the beginning of the show this week, we talked to Yash Tandon about his book Trade is War: The West’s War Against the World. At the end of this book he talks about nonviolent guerilla actions and movements that can lead to changes in the way that we structure our economy and our lives, to change the fact that, well, trade is war.

And Yash talks about all the ways people are trying to confront it, and he especially mentioned Greece. So how have you seen trade policies acting as war in Greece, and how are people responding?

CG: The Greek people are resisting what we call a financial dictatorship. So first we have a dictatorship. Putting it this way is drawing on a collective memory of the Greek resistance against the Nazis. They are speaking about a new, post-modern form of occupation.

One of the slogans has been, “First they came with the tanks, and now they came with the banks.” I think that says it all.

CM: So you have a pamphlet called Solidarity For All: Building Hope Against Fear and Devastation, Four Years of Resistance and Solidarity. In it, it says, “The possibility of Greece breaking with the neoliberal assault on the European people is sending shockwaves through the centers of EU finance and governance. They are resorting to the 2012 script of threats, not only against the Greek people but also against their own people, in order to terrorize and extort their vote by any means. This only demonstrates that fear has changed sides.”

How are threats against Greece threats against the rest of the EU’s people as well?

CG: They are trying to make an example out of Greece by imposing these very strict neoliberal measures in Greece—but they have deepened neoliberalism in the overall EU institutions and legislation elsewhere also.

I’ll give you a concrete example. Let’s say that Germany decides to pursue this tactic in order to “save the Euro” and its own people—of course they can blame the Greeks for what has happened to them and say they don’t want to pay for the Greeks. This is the dominant discourse.

But by destroying Greece and the periphery of Europe, first of all, they destroy an outlet for their own production. Secondly, they force people—mostly young people—to migrate to Germany, to become an educated but cheap labor force that pushes down the wages of the German people themselves. And third, in reality the German government takes money through taxation from the German people to give it to Greece, and, through Greece, to return it back to the German banks. So they are bailing out the German banks, through Greece, by looting their own people as much as the Greek people.

CM: If it’s so detrimental to the EU, there’s got to be somebody else who’s profiting. To you, what explains why this process continues?

CG: During the crisis, the rich and mighty from the banks and the financial system have profited from it. What we say is that the European people are losing, but the rich and mighty are winning. In Greece, the number of millionaires has gone up during the last five or six years of austerity.

But also there is the complete evaporation of the middle classes, especially the lower middle classes, that have been impoverished. Many of the people on the streets, the “new homeless,” come from the lower middle classes, not from the working class.

CM: Is homelessness new in Greece?

CG: Relatively new, yes. Because family networks are very strong, and there is also the tradition of neighborhoods, that we help each other. Also, we have had a very high percentage of home ownership—over 80%. That is one of a number of policies that the EU and the troika don’t like, and they tell us we have to bring it down to the EU average, which is 45%. Why? Real estate. This is going to be a market for developers.

It’s not that we didn’t have homeless people before, but now it has gone up by several times. We’re talking about 20,000 new homeless people in the last three or four years alone.

CM: The Solidarity For All pamphlet states, “Despite the soothing claims that the markets are protected from a possible Grexit and/or from a write-down of part of the Greek debt, what they fear is the contamination of the political message that the undisciplined Greeks could send to other countries, most notably to the “bailed-out” (austerity-ridden and deregulated) countries of the European periphery.”

The EU could afford cutting the debt, and they could afford a Grexit—do you think that if they allowed either, that other countries would join in, or do you believe that the EU’s fear of that is paranoid and groundless?

CG: I don’t think it’s paranoid. They may not have a very concrete strategic plan, because things unfold and develop in unpredictable ways. There are always cracks in dominant systems. What they see is this process of the delegitimization of the political establishment and dominant structures, and the architecture of the EU being threatened because of the crisis and because of the mass mobilization of the European people.

If they allow the Greek people to develop a different paradigm of how a society and an economy can be run without austerity, this would become a very tangible example for other people. And in Spain Podemos is coming up: for them, this is another urgent reason to make a different example out of Greece: for the sake of the next European country.

They can sacrifice Greece. Greece is small. They can afford the economic costs, and they may think that they can restrict the political effects of the Grexit. But for them, Spain is too big to fail. This is where their fears come from.

“A catastrophe for this system doesn’t mean a catastrophe for the people, necessarily. The people don’t have to believe in it. The people have a creative force to overcome the constraints of this system.”

CM: How much do you think the ideas of Solidarity For All—or the ideas happening in Spain, for that matter—come from Latin American democratic ideals from the late nineties?

CG: They are connected very closely. You mentioned Spain as well. During the 2011 revolts around the world—when I was in the communication group of the people’s assemblies in Syntagma Square, every Sunday we had online Skype connections, public to thousands of people, between Athens, Madrid, and Barcelona.

But if there is one recent source of experience that has informed what we have been doing in Greece the most, it would be the Latin American experience. Already traditionally there have been parallels between the development of the Greek nation-state and society with Latin American states. One recent historical commonality was the dictatorships that were imposed by the US in both Latin America and in Greece.

So it is a historical bond also, of which we are very aware—especially since the Zapatista movement. Solidarity with the Zapatista movement was big in Greece. We have exchanged a lot of knowledge with activists from Latin America. The Argentinian experience with crisis, and what the people did—many of the things that are now happening in Greece, we had seen in pictures from what happened in Argentina.

And of course SYRIZA as a government now faces some of the same challenges that leftwing governments have faced in Latin America. I hope that we can learn from the mistakes or the failures of some of those leftwing Latin American governments and do better.

CM: You mentioned Argentina. There is a movie from the early 2000s by Naomi Klein, The Take, about a factory occupation in Argentina. The Solidarity For All movement has also taken control and changed the production structure of a factory in Greece. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

CG: Well, it was not Solidarity For All. Solidarity For All is just a collective that facilitates the horizontal networking of different solidarity structures; it’s a more decentralized logic. The workers from a factory that had been abandoned by its owner—the Vio.Me. factory in Thessaloniki—decided to take it over and run it. They produce house cleaning and personal cleaning stuff, like shampoos, etcetera. But in order that it can be sold to the people, it is distributed through the solidarity movement.

Solidarity For All just took on the distribution side of this. We managed to create a cooperative. And actually the distribution of the products of Vio.Me. is legal, but their production is still illegal.

But it is also a matter of how we try to change legislation and provide a more favorable institutional framework for these kinds of self-organized structures to emerge, so they might become generalized practices instead of just pockets of good, willing people establishing temporary autonomous zones.

We don’t want to be the alternative in a generalized system of inequality and injustice. We want to be the mainstream. This is the end goal that we have to have if we want to change the society with the people at the forefront.

CM: On the This is Hell! Facebook page, we have had listeners post links to articles that have leftwing critiques of SYRIZA. What do you think is a legitimate leftwing critique of what SYRIZA has done so far?

CG: There are various left criticisms of SYRIZA. One is what I would call an ideological critique—measuring SYRIZA on whether it ticks all the boxes of what it means to have a left government: that it is anti-privatization, raises wages back to what they were before the crisis (to 750 euros instead of the 560 that it is now), and all that stuff. But I think this is very easy.

For me, a good left criticism would examine what SYRIZA does as a party and as a government to prepare and help the Greek people, and Greek society, be better organized to open up a different alternative. Whether SYRIZA proposes and supports this course, and changes the correlations of power to enable a different kind of politics, for me would be the criteria for a legitimate critique.

I would like SYRIZA to have done more (not just since SYRIZA has been in government, but since 2012) to have prepared Greek society and the Greek people better to have a more offensive position. “It is your choice, Europeans, whether to kick us out or not, because we can do it without you.” I think they could have been more constructive and proactive in terms of developing more options in Greek society, because there existed such potential in Greek society—there still is.

CM: Your report states, “Things are dire in Greece. Poverty has skyrocketed; there has been a great leap backward in children’s well-being, according to UNICEF; debts are up; taxes are up.”

Could things get worse?

CG: Things can always get worse. I don’t think there is a bottom of the barrel, as we say in Greece. At the same time, though, despite this kind of deterioration of the general social and economic conditions in Greece, there are other more positive results. I’ve been active since my teen years—and I don’t remember seeing, in the eighties, so many people becoming part of a collective movement in Greece.

The system is trying to impose its own catastrophe on the people, but a catastrophe for this system doesn’t mean a catastrophe for the people, necessarily. The people don’t have to believe in it. The people have a creative force to overcome the constraints of this system, and we see moments of this in Greece, especially in the solidarity movement.

CM: Just a couple more questions for you, Chris. In the pamphlet that you guys have, you talk about the social solidarity services, food solidarity structures, healthcare solidarity structures. There are all these different, weird, new ways to approach things and give people services in a moneyless fashion. The report states how the “cooperatives acquire practices that contest the prevailing organizations of everyday life.”

How would everyday life change if those social structures were everyday life for everybody in Greece?

“This has the ability to change how we think about public goods as commons. And this is happening in a very tangible way.”

CG: These structures are completely people-driven. First of all, as you said, they are moneyless. So people offer their skills and their time voluntarily, and the people who enjoy the services enjoy them for free. But the important thing about the existence of the solidarity structures is that they create these collective community spaces where democracy is actually practiced at an everyday level.

The aim of these solidarity structures is not only to provide food help, healthcare help, etcetera. It is also to engage those people that are in need to become part of the solidarity movement, and become part of building the conditions for a solution for everyone.

CM: And in the pamphlet it says that Solidarity For All and these social structures don’t mean to be a replacement for the public welfare system.

CG: Right. But we are producing a different model that can also change the public welfare system per se by making it more accountable and managed by the people themselves, by creating these participatory spaces where people can have a say about what kind of healthcare they want, what kind of education, how they can build direct networks between farmers and consumers outside the official market, etcetera.

I will give you one very concrete example. One of the most successful campaigns of the solidarity movement is the collection and redistribution of medicine. Because of austerity, even medicine has become scarce for public hospitals. But in our fridges in Greece, because we suffer from this culture of over-prescription, we have many medicines. So the solidarity structures asked for people to bring medicine they didn’t need anymore. They collect medicine in this way and give it to people who can’t afford it anymore.

In Greece, we have had three million people excluded—just in recent years—from the welfare system because of austerity and the restructuring programs. We have more people excluded from the public healthcare system than you do in the US. We were better off than you until five years ago, but now we’re much worse.

When people go to the solidarity clinics to receive medicine, they develop a different understanding of what medicine means. They return the medicines that they don’t need to the clinic. This never happened before in the public healthcare system. The public healthcare system secured universal access to health services, but it didn’t change this relationship between doctors and patients.

There are other ways the solidarity structures build a different kind of social relationship between doctor and patient: there is a greater acknowledgment of causes—whether patients have enough to eat, if they have electricity and they can cook or not become concerns of the doctor. It’s a different approach that brings a different kind of social relationship of trust and respect and equality and common contribution from all, for all.

This is why it has the ability to change how we think about public goods as commons. This is happening in a very tangible way. Not just in the theoretical way I speak.

CM: Can the EU, through those debt talks, stop whatever revolution that Solidarity For All, the solidarity structures, and SYRIZA hope for, for Greece? Can they destroy all of that at the debt negotiating table?

CG: I think they will try. But I don’t think they will manage. Because even if they manage to suffocate the Greek economy, I’m pretty sure—as we learned from the Argentinian experience, which was much farther from Europe—that other people in Europe will take up the cause and all together we will succeed to strike a blow against all these extra-democratic institutions that protect the rich and try to make the poor pay.

CM: Let’s say the EU wanted to get rid of the solidarity movement. Could they do something incredibly kind to Greece, like suddenly excusing all of Greece’s debt? Would that undermine the solidarity movement?

CG: It may undermine some of the particular forms that the solidarity movement uses now. But I think that at the same time it will be perceived as a political success for this movement. What the troika cannot undo is this movement’s proposal for a different kind of social organization. With real resources, these kinds of democratic, self-organized spaces may be able to expand outside of meeting only immediate needs, to working on how we decide about other models like what kind of state we want, what kind of education, what kind of culture.

CM: It’s really great to see that there seems to be a long game going on right now with an alternative way of approaching everyday life. I’m very excited that some things are coming out of it, like your group Solidarity For All, as well as SYRIZA and Podemos.

It’s really a pleasure to have you here, Chris. Thank you very much.

CG: Thank you very much.

Antidote has more on the solidarity structures in Greece (here and here, to begin with). But not a lot more. Yet. Something to add? antidote[at]riseup[dot]net or @AntidoteZine on Twitter.

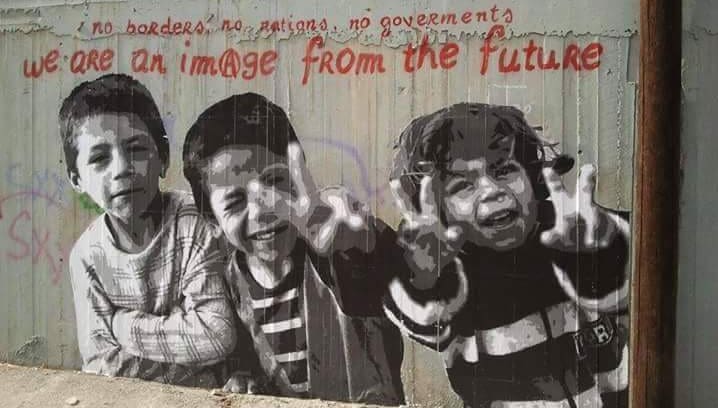

Featured Image: The playground at the collectively-built Navarinou Park, Exarchia, Athens