Transcribed from the 18 July 2015 episode of This is Hell! Radio and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

“In Egypt in 2011, they were where Burma was in 1988. Burma has a very long history, now, of resistance to military rule, and different ways to go about that. It’s not just about getting millions of people into the streets, that’s not good enough. What do you do next?”

Chuck Mertz: Award-winning reporter Delphine Schrank went undercover inside the military junta-ruled nation of Burma to find out how a resistance movement overcame decades of abuse, arrests, torture, and deadly violence to finally challenge the dictatorship.

Delphine, thanks for being on our show this morning.

Delphine Schrank: Thank you so much for having me, Chuck.

CM: Delphine is author of The Rebel of Rangoon: A Tale of Defiance and Deliverance in Burma. Delphine was the Burma correspondent for the Washington Post, where she was an editor and staff writer.

You write of Burma—Myanmar—as “a country whose very choice of names since 1989 bespeaks one’s political sympathies.” So what political sympathies does either name reveal? And why do you use the name Burma?

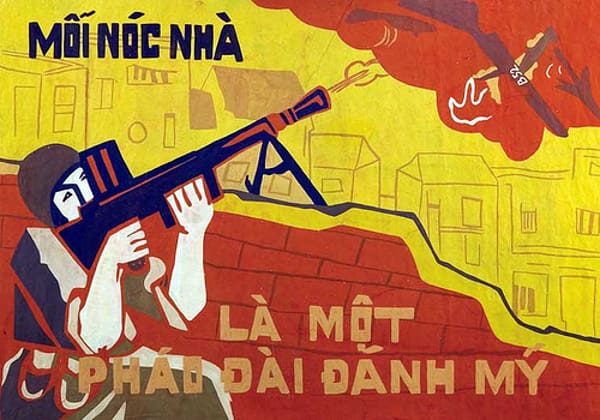

DS: There was a massive uprising in Burma in 1988 in which millions of people poured into the streets to kick out a military general called General Ne Win. And they managed to kick him out, and there was going to be a regime change, and it seemed like parliamentary democracy was on its way. But the military had never retreated to the barracks, and, in a counterrevolution, took over the country.

A junta calling itself the State Law and Order Restoration Council, the SLORC, took over and began twenty years of deeply repressive rule. In 1989 they changed the country’s name from Burma to Myanmar.

Democracy activists persisted in calling it Burma, and persisted in calling the capital city at the time Rangoon instead of Yangon. The United States recognized that; several holdouts in the West recognized that; the United Nations ended up calling it Myanmar. So ever since then, people who recognize the legitimacy of the democracy movement, the legitimacy of a political party that won elections in 1990, the National League for Democracy—they prefer to call it Burma.

As for me, I persist in calling it Burma because the protagonist of my book would prefer to call it that.

CM: You originally go to Burma to cover the aftermath of tropical cyclone Nargis, which ended up taking nearly 140,000 lives and made landfall in Burma on May 2nd, 2008. How was the response of the government affected by the type of government it was (a military junta)?

DS: All we know of the junta, really, was that it was a faceless band of generals who had brutally repressed their people for years, and had complete control of the economy, politics, and every aspect of society—even co-opting religion.

So when tropical cyclone Nargis hit (it was the most lethal natural disaster in the world since the Asian tsunami in 2004: about 138,000 people were dead or missing; the numbers were climbing very quickly), the military junta was dragging its feet.

It had, three years before that, relocated the capital from Rangoon to a new city built from scratch in the middle of the country, a city called Naypyidaw. A bit like the Pyongyang of Burma. And from that central zone it was more isolated from the people.

When tropical cyclone Nargis hit, international aid workers immediately wanted to come into the country; the junta dragged its feet and would not let them in. Those who were already in the country managed to get to the storm-ravaged zones, but beyond that it was more or less impossible to bring emergency aid to storm survivors.

That was fairly typical of the way that the junta operated at the time, that it neglected its own people and refused to recognize actual emergencies happening all over the country.

CM: The Burmese military junta refused visas to international aid workers in the wake of tropical storm Nargis, just as they had limited access to journalists since the late 1980s.

That leads me to two questions. The first is, if you’re an all-controlling military junta, why prioritize your image over the safety and well-being of your citizens? The second is, what didn’t they want journalists to see?

DS: They were completely divorced from the realities within the country. The reality was that Burma had been a country that, at independence from Britain in 1948, was considered the shining promise of southeast Asia. It is a country of about 51 million people. It’s significantly large. Huge natural resources, great social mobility.

But over the course of fifty years of successive military rulers, it was steadily impoverished and became one of the poorest countries in Asia. At the time of tropical cyclone Nargis, 2008, the reason that there was such an extraordinarily high death toll was that people were living in tiny little straw huts that a little bit of wind would just blow away. It took just one bad rainstorm, and over 100,000 people were wiped away.

The junta didn’t want to recognize it, because it was the junta’s mismanagement—and particularly that of the strongman who headed the junta at the time, a man called Senior General Than Shwe—that was responsible. It was a classic case of a tyrannical leader not wanting to recognize the reality of the impoverishment of the country he had charge of.

So they wanted, first of all, to deny the damage. And they certainly wanted to prevent outside analysts—and even their own people—from recognizing what was going on.

But I think also they just weren’t aware of it. They were completely detached and divorced from the realities of their own people.

CM: You write, “The storm was the worst natural catastrophe to hit Burma in modern times. Its ferocity was briefly matched by the response of the population as they tuned into illicit shortwave radio broadcasts and heard how their government first denied the extent of the damage, then blocked foreign aid from reaching survivors.

“So they took it upon themselves. I watched them gather at dawn and by night across the tree-clogged intersections of Rangoon—monks, bands of friends, actors, doctors, housewives, colleagues, whole neighborhoods. For days at a time they shuttered their shops and clinics, hired trucks and boats, and threw together bags of rice, blankets, candles, soap, and cooking oil. They negotiated and fought their way through checkpoints and army convoys, surrendering goods when ordered, clinging to the rest, and rattling for hours down the lone broken road to the delta or navigating a maze of tide-locked rivulets, to find survivors in dozens of forsaken towns and villages.

“They returned with tales of official confiscations and neglect, of bloated bodies floating in the bracken rice paddies, of frail men and women evicted from refuges to nonexistent homes, of government rice handouts fit only for pigs.”

How much is the organization that was created in the wake of tropical cyclone Nargis—and the organization of the opposition—due to the opposition movement’s already growing capacity? Did the response to tropical cyclone Nargis reflect how well the opposition was already organizing, or did it spur the opposition to become a better and more organized force?

DS: It’s actually a combination of both, I would say. On my first trip to Burma, the important thing became seeing that, recognizing that. I had been told that civil social organization of that nature—people’s ability to help themselves, and to organize and help other people, in the absence of their government—was more or less nonexistent.

There were, of course, a whole slew of extraordinarily oppressive laws, and a police state with informers and spies everywhere. People were terribly afraid. The junta operated by fear. But after Nargis people were organizing, and finding ways to get down to the delta—and it was very visible.

So as to the question of whether Nargis was the impetus for that—certainly, in a way, it was. Only eight months before, there had been street protests that the world came to know as the Saffron Revolution, led by Buddhist monks calling for lovingkindness. And it had been brutally suppressed. Snuffed out. So eight months later, when tropical cyclone Nargis hit, people were still afraid.

And yet they found ways to bring help down to the delta. I think on the one hand Nargis was an impetus that gave them a creative way to get around the junta. There were ways to gather together, there were ways to bring aid, and they could always just say, “We’re just bringing aid down to these people, you can’t reproach us for that.”

But it also reflected an underlying desire to bring about change. The people that were doing this were themselves hit by the storm, and lived barely above a subsistence level. The fact that they organized so quickly suggests that there was an underlying ability to gather together and connect and tap into the web of alliances that any society inevitably has, and that the Burmese society could have maintained throughout years of repressive rule.

“Monks happen to be behind this. But it’s just boilerplate racism, not Buddhism.”

CM: So did Nargis give cover to the revolution?

DS: To some degree, yes. Well, some people really just wanted to deliver help, and were refugees, were people whose own houses had been blown away. But there were also a lot of activists resurfacing who had been hiding since the protests eight months before.

Many monks and other political activists who had led protests had had to go underground. But they were able to use the chaos and the opportunity of what followed in the wake of tropical cyclone Nargis to again rise out of the underground and find ways to get down to the delta and help out, and through that, to reconnect.

So yes. Tropical cyclone Nargis, through the tragedy of it, allowed people to prove that they were able to do something, and that in itself is empowering for a society.

CM: You write you knew very little about Burma—but nobody knew much about Burma, as the military junta had closed off the country to outside eyes for two decades. Because of a lack of information, there’s plenty of space for us to speculate. So what did you expect about Burma that ended up not being true?

DS: The top one was that political resistance was dead. Like I say, I’d been told that. Yes, I knew next to nothing of the country—I could barely place it on a map, and I had about a four-day scramble to get myself there and to get down to the storm-ravaged zones, which, as I understood, were blocked by military checkpoints. And as a foreign journalist I wasn’t allowed in (I was working undercover while I was there; I had to pretend I was not a journalist at a time when there were very few foreigners in the country). So it was going to be very difficult.

Really all I knew was that Burma was ruled by a band of faceless generals, and likewise that there was a democracy icon whose name I couldn’t pronounce (I can now), Aung San Suu Kyi, who was languishing under house arrest in the middle of Rangoon somewhere. And that beyond her there was nothing. That’s what I heard.

And as it turns out, there was a lot of activity going on. The more I scratched at that, the more I began to understand what was really behind what I was seeing—a spirit of defiance and dissidence—and the more I saw how far-reaching it was.

That exists, at the same time, within a very deep-rooted culture of fear. That much was true. As I was saying, the junta operated through fear. It was their great mechanism of control. So to find political resistance alive and well—not very visible, and in very, very creative and subtle ways—was the biggest surprise.

CM: You write, “Like the Burmese, I learned to see the holes in the system of the junta, to tell a half-truth, to blink and smile and speak in metaphors. To my editor in Washington and sources in Burma, I emailed cryptic messages under an absurd pseudonym, and when I emerged, I wrote about storm survivors’ efforts to rebuild, the effects of general economic collapse, the political rite of passage that was prison, a rising generation of activists, and the emergence of a citizen movement fueled on quiet rage.”

How big are those holes? And how are they to navigate? How did you get around the junta in Burma?

DS: I was very lucky. I had one contact in Burma, a Burmese doctor. I couldn’t tell him in advance, via email, that I was a Washington Post reporter, because I knew that email was monitored on both ends, and I didn’t want him to get in trouble. He was my only local contact, and I had one other contact, a foreign man doing humanitarian work in Burma. So I didn’t really know what to expect.

When I met the Burmese doctor, he started introducing me to people. It was really through his guidance and the guidance of Burmese citizens that I learned how you talk around issues, and that you couldn’t directly ask questions about politics—people would shut up like clams. It was an intuitive learning process, person by person. You meet someone, you look them in the eye, you get a sense of whether they’re going to talk to you or not, and then you sort of feel your way into a conversation. I think through that I kind of figured out how you can talk to people under very, very repressive rules that prevent them from talking openly and directly about certain issues.

And as I would go back over time, it became easier to enter into these conversations with complete strangers. Because of course as I got to know other people, they would speak to me very openly, in a way that they couldn’t to each other—they had to be very careful of what they were saying, because of who might overhear it.

CM: You write about 2007, “A small, isolated protest of civilians and monks broke out in towns and cities; most were rapidly snuffed out. A report spread about violence of state officials against monks in the northern town of Pakokku on September 5th. They managed a week of steadily-swelling marches, joined by growing numbers of civilians, before security forces brutally charged in.”

So here I am supporting the Saffron Revolution, supporting these Buddhist monks standing up to the junta. And then I read about Buddhist monks who are killing Rohingya Muslims. How should I wrap my head around the apparent contradiction of standing up to authority while imposing oppression on a minority?

“The people that were doing this were themselves hit by the storm, and lived barely above a subsistence level. The fact that they organized so quickly suggests that there was an underlying web of alliances—that any society inevitably has, and that the Burmese society could have maintained throughout years of repressive rule.”

DS: Well, the Buddhist clergy in Burma comprises about 400,000 monks. It’s about the same size as the Burmese army. Because in Theravada Buddhism, which is the Buddhism we’re talking about in Burma, men go in and out of the monastery. Virtually every young man becomes a monk at one point and leaves again. So we’re not necessarily talking about the same individuals.

I’ll say this: on my last trip to Burma I met with the ultra-nationalist monk who is considered to be the spiritual leader of the hateful movement that uses the name of Buddhism to attack the Rohingya and the other Muslims. His name is Ashin Wirathu. And he was in prison during the 2007 Saffron Revolution. He wasn’t on the streets. He was in prison for having done exactly this, for inciting people to attack Muslims. So it’s not necessarily the same monks. That much I will say.

The second thing is that in 2007, when the monks were on the street, they were not, initially, preaching something political. They were chanting the Metta Sutta, which is a chant of lovingkindness. The protests took on a political character later. Whereas now, the name of Buddhism is used by the movement around Ashin Wirathu, but as far as I’ve been able to gage there’s really no textual basis in Buddhist scriptures to justify it.

So he happens to be a monk, and monks happen to be behind this. But it’s just boilerplate racism, not Buddhism. It’s nasty catchphrases about how “the Muslims are raping our women and destroying the Buddhist character and they’re the greatest threat to the country.”

I should say that the Muslim population in Burma, of which the Rohingya are a very small part, is about 4%. The entire Rohingya population is one million, in a land of 51 million people. So these are just distorted, hate-filled ideas that don’t correspond to Buddhism or to the larger Buddhist project of the country.

CM: But how much traction are they getting in Burma? Are they another alternative political faction opposed to the junta? Or are they just a front for the junta, which is exploiting vulnerabilities and trying to divide and conquer the population?

DS: Well, first of all the junta dissolved itself in March 2011, and put in place a system of parliamentary, sort of quasi-civilian government. The new himself had formerly been the number four general in the junta. But they took off their uniforms, so there is a supposedly civilian government.

The connections of the government with the Buddhist ultra-nationalist movement that has incited violence against Muslims and Rohingya in Burma (although that has been a long-standing phenomenon, I should say, we just didn’t notice until very recently) remain tenuous. When we’re talking about the government we’re no longer talking about a monolith, although there are different elements of the military who still wield a huge amount of power. Are they connected to Ashin Wirathu? It’s very possible. There have been meetings between Wirathu and members of the military.

Calling them a front for the junta, I think, is a bit strong. But it is certainly true that they have been allowed to continue. Wirathu and other abbots have been conducting sermons in front of packed-out crowds in which they repeat the same invective, and they haven’t been clamped down on, whereas a lot of other protests that have sprung up around the country—protesting land grabs, protesting a copper mine that would have destroyed a Buddhist heritage site; students protesting, very recently, in the streets of Rangoon against an education bill they find repressive—have been clamped down on by security forces.

CM: You describe this opposition as “a community of ordinary citizens, people who knew themselves to be poor players with little time to strut and fret, even as they each took up their baton in the long and wearying effort, and insinuated themselves into that age-old tale of the little slingshot-wielder against the weaponized machinery of an all-powerful ruthless state.

“Across the years, they would not die. They would not break under the beatings and harrassments and exiles and the lies and the divide-and-conquer rule of a Senior General schooled in psychological warfare. They endured and fought back across constant brutality and half a dozen failed uprisings. They regenerated from regularly-demolished ranks, turned violent, turned peaceful, doubted themselves, educated themselves, dissipated, fragmented, thwarted the fragmentation, recruited, forged alliances, and appropriated the international legal framework to push for global action.

“Among global movements and what some like to call ‘global civil society,’ they became an international model of creative resistance.”

What do you mean by ‘creative resistance?’

DS: The democracy movement contains many different elements of society. On the one hand, it’s senior politicians who won the negated elections of 1990 and are now in their sixties and seventies maybe, but they were lawyers, doctors. They weren’t necessarily qualified to be politicians or had any intention to be, but they felt a duty to their society.

Then there are young university activists who either ended up in prison or had to flee into exile in neighboring Thailand or China or India, or even the US. Some of them used their ability to stay in touch with what was going on “inside,” to work with activists who were trying to build networks underground.

And what are those networks? They’re basically education groups. But at critical moments—at a moment like the price hike of 2007—they would be the people that would call on their networks of activists to get out into the street and lead the protests. So, across borders and within the country, they’ve been able to use organized tactics of civil disobedience and find ways to move their country forward.

I was in Burma during the Arab Spring in 2011, and I asked a young activist at the time, who appears in the book under the pseudonym Glimmer, what he thought of what’s going on in Egypt. And he said, “I’m really proud of the Egyptians! Because now they’ll always know, no matter what happens, they have taught themselves that they have the collective power to stand up and mobilize, whatever government they have.”

He seemed to have a sense of the counterrevolution that was coming in Egypt. He was saying that in Egypt in 2011, they were where Burma was in 1988. Burma has a very long history, now, of resistance to military rule, and different ways to go about that. It’s not just about getting millions of people into the streets, that’s not good enough. What do you do next?

Well, the Burmese opposition is keeping alive a viable political party, in this case the NLD—with offshoots in the meantime, like the National Democratic Force. You need to find other mechanisms. You need to teach people about their rights. You need to build a nation. The Burmese opposition understands that, and it’s taken them a very long time.

That’s the sense in which the Burmese democracy movement is creative: its capacity to evolve. I think a lot of other freedom struggles around the world can look to it for lessons, for sure.

CM: I really appreciate you being on our show this week, Delphine.

DS: Thank you so much, Chuck.