Self-Defense and Strategic Escalation Against Violent Racists

By Antidote’s Ed Sutton

Sometimes I hate being right. Of course, in the last few years, the further intensification and proliferation of racist violence in Europe and North America has been a pretty obvious horse to bet on, so my having called a couple close ones does not count as any kind of unique prescience. But even if it did, it’s nothing to celebrate when a group of visiting Greek students gets attacked by hymn-singing neo-Nazis in the heart of Zurich. “I told you so!” isn’t exactly the winningest response. One young man was hospitalized and nearly lost an eye.

I had been watching the frequency and audacity of rightwing attacks on migrants rise in Germany and France, and just a few days prior had said it wouldn’t be long until we start seeing the same shit in Switzerland. The tone of the discourse here has long been highly tolerant of intolerance, to put it mildly. To put it accurately, the Swiss radical right has been insinuating itself into the mainstream for years, gaining an important foothold during debates over EU cooperation and freedom of movement two decades ago (no to both, of course), and not looking back since.

The attack on the Greek students was last fall. Last month, there was another attack, again in a central neighborhood of Zurich (Wiedikon). This one got far more attention: an orthodox Jew was set upon in broad daylight by twenty—twenty—neo-Nazis. In front of passersby, who called the police but did not otherwise intervene.

Can you blame them? Would you have intervened? Would I have? Certainly not. Twenty neo-Nazis is a lot of neo-Nazis.

But. We need to find a way to change the parameters such that our intervention would be imaginable. Because this will not go away on its own. Indeed, the likelihood of our personally encountering such chicanery—or even facing it ourselves—only increases with each passing day of inaction. I would go on to say we need to make our intervention in this increasingly untenable situation not only imaginable, but also expected, and effective.

In other words, we need to make the price of committed Nazism and fascism higher than these sorry scrotes are willing to pay. It should not be decent caring citizens who are afraid to show their commitments in public for fear of reprisal by racist lunatics, but rather the other way around.

A Crash Course in Empathy

Now, before this essay descends into adolescent superhero fantasy or reactionary, paternalistic “peacekeeper” logic, I should be clear that I am aware of these traps. I share with many on the left a reflexive distaste for violence of any kind, both in recognition of its being frequently counterproductive and for its inherent thoughtless machismo. I am also aware that the argument I intend to make will teeter close to the brink of endorsing criminal acts—tangling with fascists often leads to tangling with law enforcement, considering that in many places the two operate in concert and even overlap.

But first of all, I think that the ethos of creative resistance popular among the autonomous left can provide ways around these pitfalls, and still be assertive and impactful. And secondly, neo-Nazis could not care less about these concerns of ours. While we flop around agonizing about pacifism, patriarchy, and police, they will continue threatening and brutalizing their racial “enemies,” burning asylum-seeker group homes, and in places where it is practically feasible, committing outright massacres (not just the United States but also Norway and Turkey come to mind).

And they are also coming after us, by which I mean primarily white, “native” leftwing opponents of their misanthropic ideology. For many years the question, shamefully, was always how many Senegalese? How many Senegalese, Iraqis, Syrians, Afghanis, Nigerians, Libyans have to get stabbed on the streets of Athens, Bristol, Calais, Dortmund, Gothenburg, Rome, Rotterdam, Zurich before the need to do something becomes impossible to ignore? It appears that the threshold, again shamefully, is quite high. But now the question is, do you want to get stabbed?

Me neither. For many (whites) in Western Europe and North America, it is difficult to imagine being confronted with a social climate in which your free expression of left or even liberal commitments could put you in physical danger (apart from at political demonstrations, where the danger of police violence is distressingly routinized). But this might not be a long ways off, and might, in a way, be just the crash course in empathy that is needed. Many previously insulated, privileged leftists may begin experiencing the kind of fear and repression long faced by migrants, gender-non-conforming people, and other targets of xenophobic ire. A few already are.

This is something already familiar to activists in Eastern Europe and the Balkans. The experience of leftists at Maidan is a general example, but there are specific cases as well, which don’t get much international attention. Among the better-circulated are the murder of Polish housing rights activist Jolanta Brzeska in Warsaw in 2011; the murder of antifascist rapper Pavlos Fyssas in Athens in 2013; and the beating of human rights activist Artan Sadiku in Skopje also in 2013.

Each of these attacks occurred in the context of escalating political tensions in those cities around issues of migration, housing, and government corruption. These are places where it was becoming less unusual for rightwing gangsters, already long in the habit of persecuting migrants and Roma, also to attack nodes of leftwing political activity such as squats and demonstrations.

Sound familiar? That’s because this is also becoming less unusual in towns and cities in Western Europe as well. Indeed, it was never really that unusual—we can shed our last desperate clinging attachments to the orientalism embedded in the statement “Well, that could never happen here.” One night last summer, a newly-squatted farmhouse was stormed by armed Nazis in Matzenried, Switzerland. And just last week the Forsthof of the Lohmeyers, a veteran anti-racist activist couple in the terrifying Nazi backwoods of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania, was burned to the ground. And this all without having mentioned the murder of Clément Méric in Paris in 2013.

Again, I regret that this “It could happen to you!” appeal appears to be what it will take to mobilize a broader, more militant antifascist front. This does not reflect well on us. But the question, to reiterate, is how, knowing this, to respond.

Learning from Experience

Let us take for granted that the liberal response—now that it has finally come—to the increasing boldness of fascist sentiment in the discourse, and the physical brutality that it makes room for, will be insufficient. Yes, shock and outrage at the use of dehumanizing language online (“and not even anonymously—under their real names!”) and at the spiking incidence of racist assault and arson, accompanied by calls for “civic courage” in the face of public racism, are all to the good. The people who drove a racist would-be instigator of violence off of a public bus last week in Munich should be praised, and have been.

But the liberal reaction to recent larger antifascist mobilizations has been telling. That local leftwing Autonomen disrupted a public campaign event held by the rightwing populist Swiss People’s Party (SVP) in Zurich’s main train station late last month—this after the uproar over the Wiedikon attack, which is apparently held by most to be an unrelated issue—was largely regarded with scorn.

And although there was plenty of glee sloshing around social media following the successful counterdemonstration to the White Man March in Liverpool, England over the weekend, there was also plenty of equivocation. People who had perhaps praised German news commentator Anja Reschke for her stern exhortation to stand up to racists now felt uncomfortable seeing it actually happen.

Why? Mostly, it seems, on the principled grounds of nonviolence and aversion to any appearance of aggressivity mentioned before. The thing is, though, there are plenty of examples to draw from which suggest the benefits of accepting a diversity of tactics and which could begin thus to quiet these objections. In other words, we’ve been here before.

This is one area in which I will claim to have a somewhat unique perspective: I was a teenager on the periphery of the punk scene in Minneapolis in the mid-nineties, when the young militant organization Anti Racist Action (ARA, apocryphally founded in Minneapolis) was in its terrible toddlerhood and causing rifts among friends more invested in the scene than I.

I overheard all the same arguments then that I am hearing now: “It’s excessive and aggressive and gross;” “It only feeds and inflates the attention-hungry Nazis, we would do better to ignore them;” “An eye for an eye leaves everyone blind;” “By using violence, you come to resemble your enemy—don’t stoop to their level.”

I found those arguments largely persuasive back then, and still do. At the same time, I have to admit: even though white supremacist activity is famously prevalent all around the Upper Midwest region (where indigenous populations appear to be a main target of racist hostility, notably in the Dakotas and northeastern Wisconsin), the Twin Cities have remained by and large “Nazifrei.” Comparing Minneapolis to similar cities especially in the American West where racist violence is more common (if not widely reported upon), it is not such a stretch to say this might be thanks in part to a few strategic, lightly-publicized shows of antifascist force, which were condemned at the time by the liberal establishment as well as the then-marginal left fringe.

“Accomplices Not Allies”

I could go on, because there are so many other examples, especially in Europe, where robust and well-defended antifascist infrastructure and assertive resistance have created in some cases quite large areas where Nazis fear to tread. But I will linger in Minneapolis for a moment longer, because obviously the pubescent ARA is not the whole story.

Minneapolis, as many readers of Antidote are likely aware, is also the home of the American Indian Movement, a radical organization famous for its activities in the sixties and seventies but which persists to this day and whose presence was palpable in my Minneapolis of the nineties. If any one group should be taking credit for establishing a No Pasarán! climate in the Twin Cities by actively demonstrating their readiness for self-defense, it is arguably AIM. There are still ‘AIM patrols’ in parts of Minneapolis—they are of a more communitarian nature, sharing food and finding accommodation for rough-sleepers on cold nights, but still cherish their capacity to intervene and settle social disputes should the need arise.

It would be interesting to find out to what extent, if any, ARA and AIM actively collaborated (or do now) in any of their efforts and actions. Maybe I will. The truth is probably disappointing, but for now I should refrain from speculating. Still, it is a vision for that kind of collaboration that I would offer now as a tentative answer to the question of how we (white or otherwise privileged antifascists) should adjust our tactics to the new, unpleasant and dangerous reality of an emboldened radical right—without, in our eagerness, either becoming “white horse” paternalistic or otherwise damaging a larger leftwing project of dismantling structures of domination.

It should not have escaped anyone’s attention that, amid the current escalating refugee “crisis” in Europe, it is refugees themselves that have already shown, in now innumerable cases, their capacity for organization and resistance in the face of violence both formal (state) and informal (racist gangs), despite being orders of magnitude more vulnerable to it (and having fewer resources to fight it) than their “native” sympathizers on the left.

Around this time last year, I bit my lip and wrote a stubbornly optimistic screed that included reference to some instances of this resistance in Athens, Berlin, Calais, and Zurich. Today I am more convinced than ever: migrants and refugees will be this century’s revolutionary vector. While many “native” leftists scream and yell after every fascist attack but generally just watch in horror (now joined by liberals) as it keeps getting worse, at which point we scream and yell some more, not realizing the extent to which our agonized howls simply fuel the Nazis’ sadism, refugees—in many cases cornered, homeless, hungry, hunted—have been figuring out how to survive and fight it.

A wealth of experience has been and is being accumulated, which (with a few notable exceptions in the cities just mentioned and elsewhere) is being ignored by both the institutional and autonomous left. One giant first step, which virtually anyone in a city housing (or imprisoning) refugees can take at minimal risk, would be to tap into it. That is, reach out.

In cities like Berlin where refugee resistance is already well-organized, there are plenty of migrant activists with plenty to tell, and ongoing campaigns that could use concrete, specific support and resources (which may or may not mean your tough-guy barricade-building skills).

In the North American context, there has already been an intense conversation underway about the participation of white “allies” within or parallel to radical (and less radical) black antiracist campaigns, as well as an intense conversation about whether this conversation should even be had (that’s the fun one). There as here, it is the humble opinion of the AWC that what should guide our activity in this regard is the “accomplice” concept outlined last year in a well-circulated blog post by Indigenous Action, if we want to avoid the “Kool-Aid Man” effect (among other alienating collaboration-killers).

But regardless of how awkwardly these collaborations are built, they could have the instantaneous effect of extending the antiracist, antifascist bulwark (the areas “where Nazis fear to tread”) also to include areas most mercilessly exposed to radical rightwing violence—the places where refugees, Roma, and other “undesirables” live. Now that would be effective organizing.

Of course, I’m not the first to have this idea. Far beyond merely babbling about it online, there are already individuals and groups doing it this way (Calais Migrant Solidarity comes to mind, and there are less formal examples in Greece and the United States). At the same time there are also individuals and groups doing it their own way (ARA, for example, is still active in various forms around many parts of the US)—that’s fine. It is not the intent of this essay to condemn any group or tactic out of hand, it should be clear.

Across the board there should be a greater tolerance for more assertive forms of resistance and self-defense, greater patience for mistakes and failures, and a greater impulse toward solidarity among groups with clear affinity.

At the end of the day, it comes down to whether “we” want to have a confrontation on our or their terms. It’s going to happen one way or the other. Similar to how I think that in order to forestall global societal breakdown we should all quit our jobs (i.e. counterintuitively), I think we should forestall the further escalation of racist violence by escalating our resistance to it. Now.

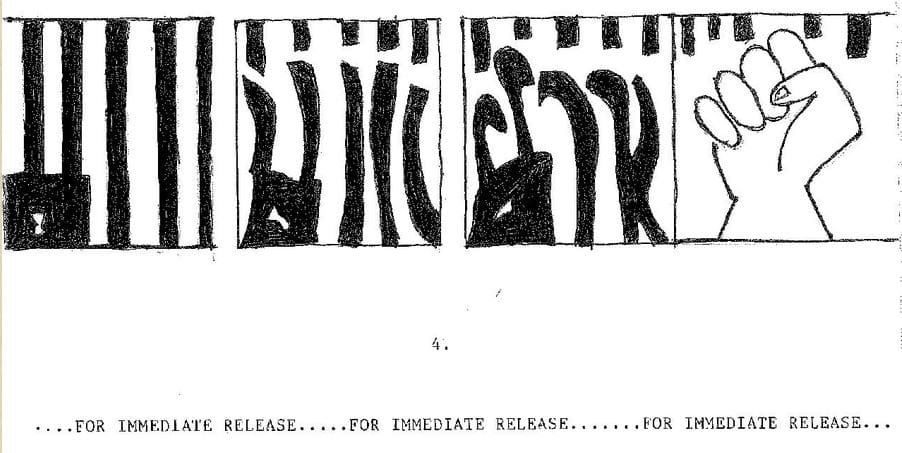

Featured image source: Places, a Critical Geographical Blog