Transcribed from the 28 November 2015 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

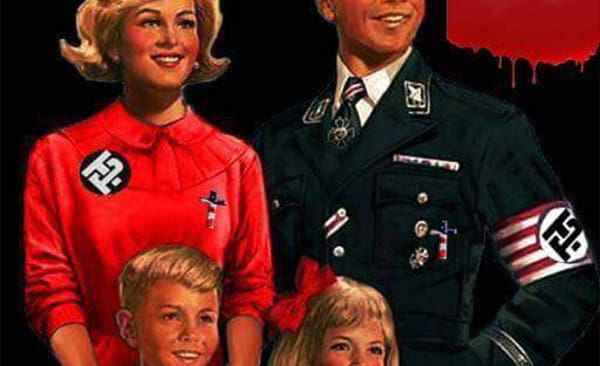

“The Islamic State is a dynamic, revolutionary movement that’s joyful. Very much like the National Socialist movement, it’s a movement of camaraderie and good feeling among its adherents; it promises to change the world for the better; and for those who are rebels looking for a cause or want to stick it to the man, it’s a great and glorious adventure.”

Chuck Mertz: The problem with ISIS is that to a lot of young people, ISIS is cool. The other problem is that US policy refuses to reflect that view. Here to tell us what makes ISIS cool to young people and what that means after the terror attacks on Paris: anthropologist Scott Atran. He co-wrote the New York Review of Books piece Paris: The War ISIS Wants with Nafees Hamid. Scott’s other recent writing includes the Guardian article Mindless Terrorists: The Truth About ISIS Is Much Worse. He is director of research and anthropology at France’s National Center for Scientific Research in Paris, and is also a senior research fellow at Harris-Manchester College at Oxford University.

Good morning, Scott.

Scott Atran: Good morning.

CM: I want to start at the very beginning with ISIS. This week there was an opinion piece in the New York Times by Kamel Daoud, a columnist for Le quotidien d’Oran. In it, Kamel argues, “Daesh has a mother: the invasion of Iraq. But it also has a father: Saudi Arabia and its religious industrial complex. Until that point is understood, battles may be won, but the war will be lost. Jihadists will be killed only to be born again in future generations and raised on the same books.”

How accurate is it to say that the invasion of Iraq is ISIS’s mother and its father is Saudi Arabia? And is there something missing from that family tree that we should know about so we can better understand ISIS?

SA: The 2003 invasion of Iraq led to a big black hole in terms of the struggle in the Muslim world between Shi’a forces and Sunni forces (which had been building up since 1979—the great turning point in history when Western hegemony was broken for the first time in a couple hundred years). It allowed the virulent strain that we see now in ISIS to emerge. But it’s not the cause.

Saudi Arabia is a great problem. The expansion of Wahhabi evangelism is a precipitator of much of this, especially the Arab Sunni revival of which Al Qaeda and ISIS are the spearhead (although the Muslim Brotherhood, which is quite opposed to the Wahhabis, and the new Deobandi movement out of Pakistan that was founded by Abul A’la Maududi were also precipitating factors).

There are many factors involved, and the Iraq War and the expansion of Wahhabism certainly have contributed to it.

CM: What would you say to Americans who don’t understand the Saudi support for ISIS while they are supposed to be the closest ally—outside of Israel—to the United States in the region?

SA: The Saudis don’t support ISIS per se. The Wahhabi movement is a little bit like the Calvinist movement in the sense that they preach obedience to the state. The Wahhabis will never challenge the Saudi ruling family as long as the Saudi ruling family permits the Wahhabis to proselytize wherever they wish to proselytize, whether it’s within Saudi Arabia or anywhere in the world.

They’re quite different than the Islamic State, even though they share many of the same basic principles. They will never oppose given Arab regimes like Saudi.

CM: I have also spoken to people who don’t understand the differences between this Islamic State and the Islamic Republic of Iran.

SA: There are striking differences between the Iranian Republic and the Islamic State. First of all, the Iranian Republic is a classical nation-state, and engages in power politics very much like other classical nation-states, and plays the world system pretty much the way it is.

Whereas the Islamic State is a truly revolutionary force which rejects the nation-state system as it exists, and its plan is to create jihadi archipelago, a global archipelago where volcanoes of jihad will erupt in areas of chaos around the world, in places like the African continent or Central Asia, and eventually, as those burst out and they become part of the Islamic State, their ideas and their wars will envelop the world, and form one world system, the world system of the Islamic State.

It’s a very, very different model. And this is according to the Islamic State’s own manifesto. According to their manifesto, the Idarat at-Tawahhush, the “Management of Savagery,” that is their plan. The Iranians are not interested in producing chaos everywhere in the world.

CM: One concern many have is the Islamophobia brought about by this war. Defenders of Islam argue that ISIS does not reflect the overwhelming majority of Muslims’ views and beliefs. In the last year, President Obama has referred to the Islamic States as “not Islamic.”

How Islamic is the Islamic State? How should we consider Islam within this context?

SA: Religions, no matter what religion, have no fixed content. What makes them survive over the centuries is the very fact that they are open-textured. They can be reinterpreted in many ways—and in contrary ways depending on who’s interpreting them.

Right now the Islamic State has a particularly brutal and virulent brand of Islam that is growing. It certainly doesn’t represent the majority. But that’s not all that important, in the sense that revolutionary vanguards rarely represent a majority of the people. They’re just the most active, and they’re able to capture the imagination of people they happen to be proselytizing to, very much like the National Socialist movement or the Bolshevik movement—or the French Revolution, for that matter. So it doesn’t matter whether or not they are the majority.

As far as “true Islam“—that makes no sense, any more than “true Christianity” makes sense. Within Islam (or Christianity, or Judaism), those who support this or that sect or this or that interpretation will always claim theirs to be true. If that works, if appeals to “true Islam,” like appeals to “true Christianity,” can work to bring people away from violence, all the better. But conceptually it’s sort of absurd.

CM: In the past year, President Obama also called the Islamic State “Al Qaeda’s JV team.” Obama told the New Yorker, “If the JV team puts on Lakers uniforms, that doesn’t make them Kobe Bryant.” To what degree is that an accurate statement? And if it’s not accurate, then what is the message the president is trying to convey?

SA: That is one of the dumbest things he’s said during his presidency. Very much like George W. Bush’s “Mission Accomplished.” I don’t think that his administration understands what the Islamic State is all about. It is the most dynamic counter-cultural movement in the world since World War II. It’s attracted people from over ninety nations. It has the largest volunteer fighting force since World War II. It has conquered hundreds of thousands of square miles of territory and rules millions of people. And it did that in less than two years.

So it represents—at least in the Middle East—a true existential danger of world-historic proportions. It fortunately doesn’t represent that kind of existential danger to our societies, at least not yet. Although in Europe, the hatchet job that both this form of radical Islam and the xenophobic ethno-nationalist right are doing on the European middle class is itself creating an existential crisis that Europe doesn’t seem to be handling very well.

“If we look at revolutionary and insurgent groups just since World War II, they have beaten armies and police with up to ten times more manpower and firepower because they rely on commitment, whereas armies and police rely on standard material incentives like pay and promotion. It’s commitment that drives these people. And the important thing to recognize is that this commitment is genuine and sincere. Otherwise it wouldn’t work.”

It is, as I said, a dynamic movement. If you look back in history, you’ll see that Al Qaeda was very much like the anarchist movement which burst upon the world scene in the late nineteenth century: killed the czar of Russia, the president of the United States, the empress of Austria, the king of Italy, untold many French leaders.

And the world response to the anarchist movement was very similar to the response to Al Qaeda. Teddy Roosevelt’s first speech after the McKinley assassination was very much like George W. Bush’s speech—in fact, almost line-for-line—after the 9/11 attacks: ‘the United States now has the right to police the world, because other nations aren’t.’ And the United States embarked on an imperial mission. In part, ostensibly, to meet the anarchist threat.

The FBI, Scotland Yard, and the precursor of the Russian NKVD all emerged to deal with the anarchist movement. Militaries were mobilized. Now, the anarchist movement wasn’t really much affected by all of that. What killed the anarchist movement was the Bolshevik revolution. The Bolsheviks co-opted much of the anti-capitalist message of the anarchist movement, and they were much more brutal. And they were territorially-based, and they were here-and-now. They could say, “We have, here, a communist utopia in the Soviet Union, and it’s eventually going to take over the world.” And this was a much more appealing argument than the anarchists’ diffuse one.

What the Bolsheviks did to the anarchists is very similar to what the Islamic State is doing to Al Qaeda. In fact, when I was talking to Nusra fighters in the Middle East recently, they themselves told me that Daesh was eating them up.

CM: So are the youth who are attracted to ISIS—are they attracted to the world that they believe will be created out of this revolution? Or are they attracted by the revolution itself? The love of the fight? What is it exactly that ISIS highlights in attracting young people?

SA: The people who join ISIS are for the most part youth in transitional stages in their lives: students, immigrants, between jobs, between mates, having left their native family and looking for a new family of friends and fellow travelers to find significance in life. About three of every four who join ISIS do it through their friends. About one in five through their family. Very few through active recruiters and anonymous strangers.

They’re looking for adventure and glory. Especially those on the margins of society increasingly find in ISIS something to give them meaning in life. I was talking to someone, for example, who wanted to blow up the American embassy in France, and I asked, “Why would you want to do that?” He gave me the whole spiel about the persecution of Muslims around the world, and I said, “Yeah, I get that. But why do you want to do it?”

And he said, “Well, I was walking down the Boulevard de la Republique with my sister, who wears a hijab. She was window shopping, and she didn’t look where she was going, and she bumped into an elderly Frenchman, who spit on the street and said, ‘You dirty Arab.’ And then I knew I had to join the jihad.”

And I said, “Well, there’s always been racism like that, in France and elsewhere.” And he said, “Yes, but the jihad didn’t exist.”

So it’s an attractor for self-seekers who are dissatisfied with their personal lives, for whatever reason, or who can be convinced by their friends that they shouldn’t be satisfied by their life for whatever reason. Perhaps they have personally suffered, perhaps not (mostly not); perhaps they have frustrated aspirations (this is often the case, especially in Europe).

One big difference between Muslims in Europe and Muslims in the United States is that the United States, regardless of foreign policy, is built to absorb immigrants (though some nutcases on the Republican right are trying to change that). And that means that within a generation, Muslims who come to the United States attain the average—in fact, surpass it—in education and economic status within the first generation.

In Europe, they are five to nineteen times more likely to be poor, even up to the third generation. In places like France, seven to eight percent of the general population is Muslim, but seventy percent of the prison population is Muslim. It’s very much like the worst of the urban ghettos in the United States; there is a permanent underclass.

Muslims who come into US prison, for example, enter “Prislam,” as the NYPD or the LAPD would call it—they might radicalize and fall into jihadi movements. They do this in order to defend themselves against white supremacists inside. But when they get out of prison, there’s no echo in the community. So there’s really no jihadi afterlife, with a few exceptions in some communities.

In Europe, the opposite is true. When they get out of prison, they go back into these vast, soulless housing projects or slums or neglected neighborhoods, and it doesn’t have the iron bars of prison, but it certainly has much of the atmosphere of prison. And there is this constant counter-cultural aspect in the community, where the community will not turn in their own. So this culture can develop, and the Islamic State provides an outlet for it.

Again, the Islamic State is a dynamic, revolutionary movement that’s joyful. People don’t understand that, because our propaganda says they’re criminals, they’re psychopaths, they’re brutal, look at what they do, they behead people. But in fact, very much like the National Socialist movement, it’s quite a joyful movement, a movement of camaraderie and good feeling among its adherents; it promises to change the world for the better; and for those who are rebels looking for a cause or want to stick it to the man, it’s a great and glorious adventure.

“Brutality and blood are the preferred way that societies have of binding themselves against enemies. It’s sublime. It’s a visceral and passionate way of creating a community. It’s truth. And it scares the hell out of enemies and fence-sitters.”

CM: How much were the attacks on Paris, then, blowback to racism and discrimination?

SA: Of course racism and intolerance of minority cultures have been a big part of it. But Europe has basically dealt with this ostrich-style. The idea was that secular pluralist Enlightenment culture would be embraced by anyone who’s exposed to it. But again, because the immigrant population has been a downtrodden, distressed population, it never really got the chance to embrace that. It was kept sort of isolated. The Enlightenment has never been successful for these people.

People talk about the “Clash of Civilizations”; in fact it’s almost the exact opposite. It’s a crash of cultures, territorial cultures and others, in which the vertical lines of communications between elders and youngers have been sundered, and young people are left flailing about looking for a new sense of significance, and they hook up with friends.

Parents have no idea what these kids are doing. It’s very rare that parents know what’s happening. These kids are hooking up horizontally and creating these new jihadi cultures—“ninja” cultures in a very tight informational bandwidth, but one which spans the globe.

And the parents, when they finally find out about it, they invoke something like “brainwashing.” This is a vapid notion, of course, that came from the Korean War when a hundred Brits and American POWs didn’t want to go home; the idea emerged of these Chinese social-engineering geniuses using Pavlov techniques to wash the brains of these soldiers, The Manchurian Candidate was written, and ever since then it’s come into popular culture. But there was never anything like it and it doesn’t exist. Still, it’s a very convenient notion for people who don’t want to pay attention to what’s going on.

Anyway, it’s also only a small percentage of young people. But it’s important to understand that even though it’s a small percentage, this can change history. Again, they are a vanguard. All revolutionary movements begin with a small vanguard. Even calling it terrorism or extremism I think I a mistake, because evolution and history only care whether it succeeds or not, as Darwin said in The Descent of Man.

Darwin had a problem. He asked, Why are there heroes and martyrs? Why are there people willing to sacrifice everything in a losing cause? This seemed to go against his first book, The Origin of Species. He said it’s because heroes and martyrs, if they can get others to follow them, can ultimately get even low-power groups to triumph over groups that are initially much stronger—to triumph in the spiraling competition for survival and dominance in our world.

In fact, if we look at revolutionary and insurgent groups just since World War II, they have beaten armies and police with up to ten times more manpower and firepower because they rely on commitment, whereas armies and police rely on standard material incentives like pay and promotion. So it’s commitment that drives these people. And the important thing to recognize is that this commitment is genuine and sincere. Otherwise it wouldn’t work.

I was on the front lines in Iraq, embedded with the peshmerga and the PKK, right near Mosul. If you can imagine the front: it’s like a medieval front of mud mounds that stretched for 1,050 kilometers just in Kurdistan alone, and roughly every kilometer there’s this round mud turret with sandbags, and in there are about twenty fighters. Some of them hadn’t left these turrets for about seven months, if they’re defending against the Islamic State.

And in a few of them, there are still Iraqi soldiers, not Kurds. Arab-Sunni soldiers. I asked them what happened, as I asked the Kurdish leaders. Back in June 2014, about eighty trucks, with four to five fighters in each truck, came to free a prison in Mosul called Badush prison; they massacred 600 Shi’a in that prison, but they released the other prisoners. And the Iraqi military forces in Mosul, trained to the tune of billions of dollars by the United States and under the personal command of the head of the Iraqi Army, with eighteen thousand troops, ran away in a matter of hours.

I asked one of the Iraqi soldiers why he stayed and why his fellow soldiers left. He said he stayed because—he pointed with his hand—there, about a kilometer and a half away, is a village that ISIS controls, and his family is there. So he stayed. But he said the others didn’t want their heads chopped off.

People think the brutality of it is a terrible thing, and how could people possibly practice it or support it? Brutality and blood are, in the history of our species, not only common, but they are the preferred way that societies have of binding themselves against enemies. It’s sublime. It’s a visceral and passionate way of creating a community. It’s truth. There’s no society in history that hasn’t been formed in blood like that. There has been no revolution that hasn’t been formed by rivers of blood. And it scares the hell out of enemies and fence-sitters.

CM: I think that’s the part that people don’t really understand: how the youth could be attracted to that kind of violence. But I also want to ask you, how much is it also because democracy or the West lacks a positive message compared to what ISIS offers?

SA: There are two aspects to it. First, does our message appeal to these young people who are on the margins? Apparently not. The dark side of globalization allows these young people to flail about until they find some positive message like Daesh’s message, which is great and glorious and adventurous.

Some of my research assistants and students dialogue with Nusra and Al Qaeda and ISIS—and they dialogue for months on end, and in a very sincere way. They say, “Look, I’m a student, I’m doing my degree at whatever university, and I want to just understand more what’s happening, and can you please…” And they enter in a very personal dialogue.

One of the great advantages of the Islamic State over our own feckless propaganda counter-narrative is they spend hundreds of hours talking to people. They try to bring them out and to try to see which way their personal stories and grievances can be wedded to the story of the change in the world that they’re proposing.

Whereas our messages, from the US State Department and others, are basically repetitive lectures for mass consumption which are completely meaningless. “Daesh cuts off heads, and they want to control your diet and dress.” They fall flat. They don’t work at all.

It’s a problem that George Orwell raised in his review of Mein Kampf in 1939. He asked: Why is it that the socialist countries, and to a more grudging extent the capitalist countries, offer their citizens ease, security, avoidance of risk, comfort, short working hours, and birth control? And why is it that our Oxford Student Union, the cream of our intellectuals, votes that they will never fight again for such values? But Mr. Hitler, what is he offering his people? He is offering adventure, glory, death and destruction, but most of all a feeling of transcendence and self-sacrifice. And so eighty million people fall down at his feet.

And how did we defeat the Germans? The Germans, by any measure, outfought—to the end of the war—all the Allied armies. The American army, the Russian army, the British army. What defeated the Germans was overwhelming firepower produced by the United States, which was an order of magnitude greater, and the willingness of Soviet leaders to throw tens of millions of people at the Nazis. The Germans couldn’t replace their losses; that finally defeated them.

“Our job is to figure out and help young people across the world who are looking for a sense of significance and transcendence and meaning in life. We’re not doing it. But I think if we do, if we are sincerely devoted to it, then things could turn out for the good.”

It wasn’t our ideas that defeated them. It certainly wasn’t a shopping mall mentality. That’s not to say that democratic ideals can’t win out in the end. If we look back at the American Revolution, whatever you might think about it: in 1776, after months of voting to separate from England—the first motions were defeated—motions were finally carried because Adams had convinced the property-less artisans in Philadelphia that they could have a stake in the new republic, and that their vote, their voice counted as much as that of anyone with property. By swaying the property-less artisans of Philadelphia, they swayed Philadelphia, and in turn swayed Pennsylvania, which controlled the Mid-Atlantic colonies, which basically controlled the majority. And so the vote to separate from England was made.

Then England sent the largest naval expeditionary force in history up to that time—hundreds of ships and thirty thousand soldiers—against New York, which only had twenty thousand inhabitants. The American army was beaten to a pulp. It was an all volunteer army, and it was about to be disbanded and the colonists were going to go back to cultivate their crops (the Americans actually had the highest standard of living in the world at the time. Much more than England itself).

And eyewitnesses say in December of that year Washington actually got up and made a speech saying that this was their one time to fight in the cause of liberty, and perhaps that cause would spread across the world. And they did. And they suffered tremendous losses. And they bonded in Valley Forge to form what was a fractious army before into a solid army. Of course, they also had the help of the French (who continue to this day to believe that they won the war). But the revolution succeeded.

Revolutions succeed because people are committed. And the question the Islamic State presents for future generations, and for the future of open societies in the world, is whether our values can mobilize “our” people to the same extent that these other values mobilize “their” people. One would hope that civil and human rights are more appealing than the kind of message that the Islamic State is preaching. But it’s not all that sure.

Again, the National Socialist movement lost by a hair’s breadth. If they had come up with nuclear weapons, they might well have won. It was very attractive to the people who belonged to them. And our message, our democracy, is much more focused now on simple material incentives. Again, comforts, good life, ease, avoidance of risk. And as Orwell said with respect to Mr. Hitler, human beings intermittently need a feeling of transcendence and self-sacrifice. That’s what brought us out of the caves. That’s what creates movements in history. That’s why civilizations rise and fall, not on the basis of material means as such. If we can mobilize our people, if they believe in our cause—that is the cause of human rights—I think it will win in the end.

But actually, human rights are a crazy notion. For 200,000 years, human beings practiced cannibalism, infanticide; every society in the world up until recently practices domination of women, intolerance of minorities…but all of the sudden a bunch of European intellectuals in the mid-eighteenth century decided otherwise.

Then the notion of individual rights developed, also for the first time in history. An Italian marquis named Cesire Becaria, writing about a water-boarding case—Jean Callas in France, who was water-boarded for heresy—argued that such torments of the body and the individual are intolerable if we want to create a free society. Adam Smith and Voltaire and Jefferson and Tom Paine took that cause up, and by the end of the century, torture was banished in England, France, the United States, and slavery was abolished—that took a little while longer—and eventually there was universal suffrage of women, which reversed 200,000 years of human history.

And that was done through war, economic competition, and social engineering. It had nothing to do with providence or the Creator or anything “natural.” In order for that to endure—and not to spread across the world, but just to survive—it’s going to take struggle, because there are countervailing forces within human beings that oppose it.

CM: Scott, I’ve got one last question for you. Our final question is always the Question from Hell, the question we might hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate the response.

Last week on the way home from the radio station, I heard a CBS News radio commentator say that “unless some modern-day version of Lawrence of Arabia appears, it looks like we’re going to be in a very long war in the Middle East.”

That comment did not sit well with me, Scott. What would you say to someone who argued that the problems in the Middle East could be fixed by a “new Lawrence of Arabia?”

SA: Well, the problems of the Middle East were in part instigated by Lawrence of Arabia, and those he was working for. I think the West’s attempts to try to control and harness these forces has been misbegotten from the beginning.

What I think our chance is for the coming generation is to listen to the young people in the world. Allow their ideas to bubble up. Many of their ideas are crazy, right? And as Alan Brooke, Churchill’s chief of staff, said about his boss winning in the Second World War: “He has ten ideas a day, one of which may be good. Our job is to try to figure out which one.”

I think our job is to try to figure out and help young people across the world who are looking for a sense of significance and transcendence and meaning in life. We’re not doing it. But I think if we do, if we are sincerely devoted to it, then things could turn out for the good.

CM: Scott, it’s truly been a pleasure, not only having you on this week’s show but also getting the opportunity to read your work. It gave me a totally new perspective about the Islamic State. I truly appreciate that opportunity. Thank you so much for being on our show this week.

SA: Thank you for your kind words.

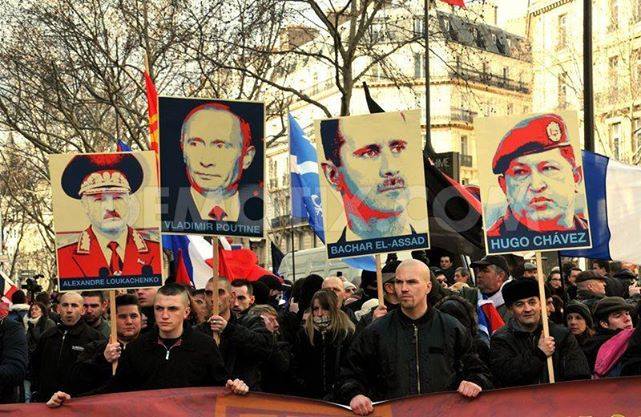

Featured image: Scene in Aleppo, summer 2015. Translation: “Down with Assad and ISIS.” Teenage rebellion takes many forms.