Transcribed from the 5 December 2015 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

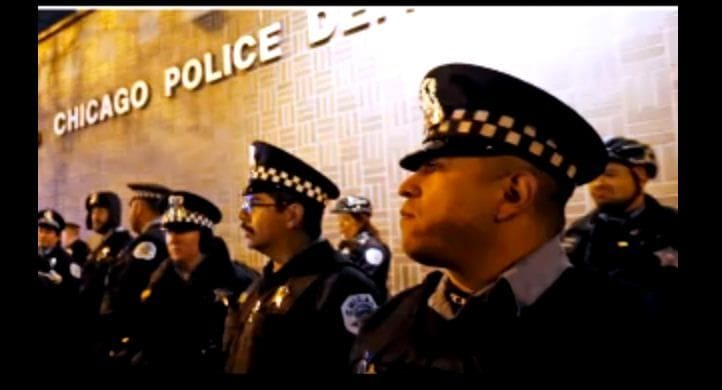

“Think if this were a routine homicide, meaning not involving the police, and you had multiple police and civilian witnesses; you had the videotape of the crime itself; you had, within less than 24 hours, the results of the autopsy, were there any doubt about the violence inflicted on the victim. They would indict within days.”

Chuck Mertz: If it were not for two journalists, to this day we would not know how Laquan McDonald died at the hands of a Chicago police officer. Right now I am very proud to welcome the journalist who was the first to see Laquan’s autopsy report, and the journalist who sued to have the police video released.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Jamie Kalven, and welcome, Brandon Smith.

Jamie Kalven: Good to be here.

Brandon Smith: Hey, I appreciate it.

CM: Brandon, let’s start with you. I just want to get your reaction to the front page of today’s Chicago Tribune. The headline says, “Video contradicts officer Van Dyke’s account, conflicts with dashcam recording of McDonald shooting.” It says that “new details that emerged from hundreds of pages of police reports released to the Tribune on Friday night show that additional police reports indicated that Van Dyke’s partner and two other officers also said that McDonald was advancing on the officers with a knife when Van Dyke opened fire. Two additional officers said McDonald was either turning toward police or threatening the officers when Van Dyke fired, according to the reports.”

So Brandon, my question to you is, how does this change the story? What does this do to the story? And more importantly, what do you think it says about the Rahm Emanuel administration when they don’t release these documents until late on a Friday night?

BS: I think the timing of the documents is more about when we filed our Freedom of Information request, and they basically complied with part of that as soon as they realized they were required to. That said, it certainly doesn’t look great for the Emanuel administration, because every officer on the scene seems to have given the story that officer Van Dyke was in the right and that the young man, Laquan McDonald, was basically being violent or threatening the officers. And of course we know that didn’t happen.

So my question is, why weren’t all these officers sought out and punished a long time ago? The video was in the possession of the prosecutor.

CM: That was journalist Brandon Smith. He runs the website Muckrakery: “Showing powerful people the consequences of their actions since 2007.”

Jamie Kalven is a writer and human rights activist at the Invisible Institute, a journalistic production company on the South Side of Chicago.

Jamie, let’s start with the shooting itself. The video that was released due to both your work, Jamie and Brandon, contradicts police reports that in October 2014, Laquan McDonald, a black teenager, lunged at a police officer with a knife, threatening the officer’s life. Instead, the video shows McDonald walking away from police officer James Van Dyke, and, from a distance, Van Dyke shoots sixteen times, completely unloading his gun, in what’s been described as an “execution-style” shooting.

Jamie, you are quoted in the Chicago Reporter as saying, “Out of concern that Laquan McDonald’s shooting wasn’t being vigorously investigated, a source told me that there was a video and that it was horrific.” In your opinion, why wasn’t this story vigorously investigated by the Sun Times, the Tribune, the Daily Herald, local CBS, NBC, ABC, FOX, PBS affiliates, Chicago Public Radio, even 780 News—what explains to you why so many media outlets, with so many more resources than you have, were not investigating the killing of a young black man by a Chicago cop?

JK: A couple of things. I think we’re treating the Laquan McDonald episode as kind of unique, and there’s one sense in which that’s justified: the extraordinary ugliness of this particular shooting. But there are a lot of things that are routine about this. You were talking with Brandon about the officers lining up, corroborating statements for Van Dyke. This is routine. This is the norm. This is what we mean when we talk about the code of silence.

The code of silence, this narrative control that the department exercises, includes the press. With shootings of this nature (they occur on average forty-plus times a year, citizens are shot by police—not all end in fatalities; eighty-plus percent are African-American victims), the press, as a general matter, publishes the police blotter.

There’s a recipe for how these stories are reported. It centrally involves the voice of either the Department or a spokesman from the Fraternal Order of Police; always the final paragraph says the Independent Police Review Authority is investigating; and there’s almost no independent reporting done on episodes of this sort.

That may change now, but it certainly has been the pattern.

CM: Brandon, you sued to get the video released, but you did not get media or press credentials for mayor Rahm Emanuel’s press conference releasing the recording. Do you think this was about retaliation toward you, or was it just a matter of the process by which the press office for Rahm Emanuel normally works?

BS: Oh, I was unsure at first. But now that I think about it, a week or two later here: they probably want me to attend the press conferences, because then I’d just be one of a hundred reporters trying to ask my one question, and they can just refuse to call on me. Which happened at the later press conference.

The point is, the administration can very easily not answer questions if they don’t want to. So it was a real blunder to not let me into the press conference. I don’t think they wanted to bar me, and they got some negative press for doing so.

CM: Jamie, at that press conference, mayor Emanuel made the “one bad apple” argument, saying one individual needs to be held accountable. But you told the Chicago Reporter that the mayor’s re-framing of the narrative is essentially false, pointing out that “the city knew from day one. They had the officers on the scene, they knew there were witnesses, they had the autopsy, they had the video, they maintained a false narrative about these events, and they did it for a year, when it would have been corrected almost immediately.”

They spent almost a year stonewalling any calls for transparency on any information about the case. Jamie, what would you say if someone argued it was an ongoing investigation? Or that in fact, it even went more quickly than usual? Thirteen months, when these kinds of investigations usually take eighteen months. And the city eventually quit fighting the release of the video.

Was this stonewalling? Was this being thorough? Or was this a cover-up?

When I posted on social media that this was a cover-up, I had a lot of people replying that this is not a cover-up; this is the amount of time these kinds of investigations take.

JK: Maybe the best way to think about it is if this were a routine homicide, meaning not involving the police, or if it were a gang shooting. And you had multiple police and civilian witnesses; you had the videotape of the crime itself; you had, within less than 24 hours, the results of the autopsy, were there any doubt about the violence inflicted on the victim. They would indict within days.

The city had all of that in the Laquan McDonald case, within a matter of hours. So we have to say that this has been an instance of “investigation as cover-up.” This has now been completely upended as a strategy, and I don’t think it will be possible to proceed the same way again in the future. But the way they’ve always handled this is: as long as you can say there is an investigation pending, you can stonewall press inquiries and public inquiries, and you can suppress public information on the grounds that it might conceivably in some way have a bearing on the investigation, or its release might do damage to the investigation.

That line of reasoning, I think, has been completely impeached—and not just in this case but for the future—by the uproar over Laquan McDonald.

CM: Brandon, you said you were dismayed when reporters from the establishment media asked you if you were concerned that the video’s release would lead to violence. Columbia Journalism Review quoted you saying, “Am I concerned? Yes, it keeps me up at night. But to focus stories on any potential or possible violence rather than the larger trend of violence already perpetrated by police is irresponsible.”

So you must have loved the coverage of the Black Friday protests that took place on Michigan Avenue, with every local news channel starting with the impact the march had on shopping—how it hurt downtown employees who work in the service industry and depend on tips, how it angered shoppers—and had nothing on the story of police violence.

As friend of the show Fred Lonberg-Holm told us, they should have changed the hashtag to #BlackFridayMatters instead of #BlackLivesMatter.

What did that reveal to you about the media here in Chicago, Brandon, when it focused on the inconvenience of shoppers instead of discussing, or continuing, an investigation into the problems of the Chicago Police Department?

BS: The funniest thing about that is the idea that the media covering the protests as they did just proves the narrative of the protesters. The narrative of the protesters, the reason they were in a shopping district, is that the system—the status quo police and administrative system, as well as media that don’t keep them in check—cares more about shopping and economic success than they care about violence perpetrated against certain groups of people. It’s funny that the media didn’t listen to the protesters’ claim, and we know that they didn’t, because they covered the protest from precisely that frame that the protesters were criticizing.

I say the system: Jamie talked about “investigation as cover-up.” The city says they’re investigating but what they’re really doing is providing themselves cover so they don’t have to release information. That statement, “we are investigating,” gives the idea that justice is being done. So reporters kind of drop it.

But because this is such a big story now, it is going to allow reporters all over the country to ask, “Well, how are you investigating? Let’s figure out why it’s taking so long.” I talked to a whistle-blower from IPRA just yesterday, Lorenzo Davis. He’s a veteran of that agency and a veteran of investigating police misconduct. And he said an investigation should have taken a couple of weeks, echoing what Jamie said. It’s just nonsensical.

“The procedural protections police officers enjoy exceed those of any other citizens, including children and the mentally ill. That really gums up the works in terms of accountability.”

CM: Brandon, I know you’ve got to go, so let me ask you one more question and then we’ll continue with Jamie.

Brandon, I’m interested in whether you’ve had any blowback from your reporting. I know people who have been in court cases against the police department before, and they say that their personal lives become a nightmare.

BS: It’s not such a big deal for me. I’ve been inconvenienced a few times, but that’s of no consequence compared to the kind of violence we’re seeing. I still go home, and I sleep in a bed every night. I’m warm, and I eat. Maybe not as well as some other people in the media. But I eat. And I am by and large not afraid of the police. The scary, terrible fact remains that a lot of people have reason to be afraid of the police, because in their neighborhoods police act very differently than they do in many other neighborhoods.

I just really want that to change, and Jamie and I and others are going to try to work to change that.

CM: Brandon, thanks so much for being on with us. I’ll let you go, and continue with Jamie.

BS: Really appreciate it, guys, thank you.

CM: Jamie, what does it tell us about the police union when the press spokesman of the Fraternal Order of Police, Pat Camden, a retired long-time cop, misleads the public and the press at the scene of the crime, considering he is the person whose reports the establishment media here in Chicago take verbatim? What does that tell us about the police union?

JK: I think it says more about the media than about the union. I think there are a lot of things to say about the union, but the Pat Camden phenomenon is much more a matter of how the press culture works in Chicago, that they just accept Camden’s accounts of the scene. He’s done this probably close to four hundred times at police-involved shootings, by his own count.

Initially, for a number of years—decades—he was the spokesman for the police department. Several years after his retirement, he resumed in a similar role for the Fraternal Order of Police. The fact that the press in all those instances has largely uncritically accepted his account of what happened as the account, and then broadcast it as the dominant narrative of what happened—that really reflects on the press.

I think there are a lot of issues about the police union, and they are reflected to some degree by the Pat Camden phenomenon, and I know this from talking from Dean Angelo and others: they see their role as representing their members. Even in an instance like Van Dyke’s shooting of Laquan McDonald, that’s just how they see their role.

There are all sorts of provisions in the police contract that are really antithetical to the public interest. Police officers, when they’re involved in shootings or allegations of serious abuse, have so much “due process.” It’s fair to say that the procedural protections police officers enjoy exceed those of any other citizens, including children and the mentally ill. That really gums up the works in terms of police accountability.

There’s also an issue you and your listeners should be aware of; we’ve been in a fight with the police union—the Invisible Institute, my colleagues and myself, and the two newspapers in Chicago. In March 2014, there was a court decision in a case I brought, Kalven v. Chicago, which really established the principle that police misconduct files are public information, subject to minor redaction (redaction that nobody would quarrel with: personal information, social security numbers, home addresses and such). But the names of officers and the substance of abuse allegations and investigations are public.

After that decision came down and after we negotiated a transparency policy with the city for implementing the decision, both newspapers and I made FOIA requests for the entire disciplinary history of every officer that has served on the police force going back to 1967. Essentially the entire database for the modern era of policing in Chicago. Remarkably, the city agreed to the FOIA request without litigation. They agreed to give us this extraordinary data dump which will be extremely revelatory when we can dig into it.

At that point the Fraternal Order of Police intervened and found a sympathetic judge, who imposed a temporary injunction that we’re currently litigating. Their grounds were that the release of the information would violate their contract. There are provisions in the FOP contract, for example, that police misconduct records should only be retained for five or seven years depending on the nature of the complaint.

The FOP—and they have some traction—is basically pressing for a huge bonfire that would destroy records that the public has only recently, through the decision in my case, gotten access to. At a time when we’re talking about federal investigations, and the mayor has created a taskforce, and there’s this moment for examining the systems of accountability in the city—this is precisely the evidence needed for that, but the FOP is making this major counter-attack.

The union is a force to be contended with, and I urge everybody to be alert to this most immediate and current issue about preserving these files. Because it’s really critical. How can you make a diagnosis of an alien system if you don’t have this kind of information?

CM: Can we have successful reform of the Chicago Police Department without having some sort of reform of their union, the Fraternal Order of Police?

JK: It’s definitely on the agenda. I want to be clear: police, like other workers, surely need union representation. But the status of police is something beyond that of workers—who should get decent wages, benefits, working conditions, which you absolutely need union representation to ensure. But take the point I was just making about these documents, which really belong to the public. The documents belong to the public. The idea that the city and the union, in the context of collective bargaining, could bargain away our right is where it gets problematic.

Bargaining on behalf of police officers regarding employment conditions is a completely legitimate function. But the FOP goes way beyond that. There are provisions and protections for officers that really impede investigations and, hence, enable abusers. So yeah, among the various things that need to be addressed going forward, the role of the police union is definitely one of them.

“All of us need to be worthy of this moment, worthy of this opportunity. We’re talking here about saving lives. The stakes are really high at the moment.”

CM: Jamie, you believe these kinds of videos should be released within 24 hours of being recorded: “They should be released within 24 hours unless there are compelling investigatory reasons to hold on longer. The policy should be that the presumption is that this is public information, and it gets released as quickly as can reasonably be done, except in cases where there is a genuine and very specific investigatory need to withhold it.”

Curtis Black at the Chicago Reporter then argues, “Instead of vague and politically self-serving calls for ‘healing,’ it could have begun a process of accountability of the kind necessary to start addressing the extreme alienation between the police and wide segments of our communities.”

Do you think such a release would bring more accountability? Or—as everyone in the establishment media tells me—violence?

JK: It demonstrably hasn’t brought violence. I think we should be proud of the city and of the protesters. There were widespread fears before the release of the video that the demonstrations would be violent and there would be disorder. But the demonstrations have been extraordinarily effective and, in that form of public theater, eloquent.

I’ve done a lot of black talk radio in the last couple of weeks, and we’ve talked about that with people in the studio and with people calling in. And there’s a very strong sentiment in the black community: “Come on, we know this stuff happens. We know this stuff happens in our neighborhoods.” If the mayor and the administration had been forthcoming about it, whether they released the video or not, it would have built public confidence, including in communities that are—and have reason to be—alienated from law enforcement.

But for us to know that the city had this information from day one, and used every means at its disposal to withhold it from the public—that’s tremendously undermining of public confidence. In the year-plus since Laquan McDonald was shot, we’ve seen a number of instances in other jurisdictions where cities have handled it much better.

The most striking example is Cincinnati, I believe the name of the victim was Samuel DuBose: a campus police officer stops and ultimately shoots and kills a motorist. Cincinnati had adopted a policy of timely release, within 24 hours, of video and other evidence of this nature, after a problematic incident. And they held it, actually, for a full week before they released it, but the reason they held it was they were looking into a couple of other officers—speaking of the code of silence—who had corroborated the shooter’s false story. The officers had provided statements about what had happened that were pure fiction.

So they deferred the release of the video for a week in order to nail those officers in their false statements. That seems to me a legitimate reason to withhold public information, and they only did it for a week. That’s what real accountability looks like. That builds confidence.

But in Chicago there was just this broad assertion that an investigation is in progress, and hence this information that belongs to the public could not be released. That just won’t past muster anymore. I think there’s every reason to believe that we will soon have a policy in Chicago that much more resembles Cincinnati’s.

CM: Jamie, Brandon is lucky because he bailed. At the end of the interview we ask a Question from Hell, the question we might hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate the response. You’re still around, so you’re stuck with the question.

You write about how the underlying conditions that shield abuse still continue. Do those underlying conditions go away with the resignation of Chicago Police Superintendent Garry McCarthy, or even the impeachment of Anita Alvarez, or the resignation of Rahm Emanuel? Does any of that make deadly police violence and the police cover-up culture go away?

JK: That’s the question of the moment, and I appreciate it. I was glad to see McCarthy go, but I was also glad to see that nobody was satisfied by his firing as adequate reform. I think it did, as the mayor put it, “remove a distraction.” I very much expect to see State’s Attorney Alvarez voted out of office in March, if she doesn’t leave before that.

I have somewhat different feelings about the mayor in this. First of all, there’s no way he did not know about this case. If not from the first day, certainly from the moment, roughly a year ago, when Craig Futterman and I first made public the existence of the video and called on the city to release it. Within minutes of the posting of my article on Slate, the full text of the article was in the email boxes of the mayor’s entire senior staff—we know that because Carol Marin at NBC FOIAed the city’s email traffic around the Laquan McDonald case. So there’s been knowledge, and we have to hold the mayor accountable for that. He’s implicated in this deplorable episode.

Having said that, I think that he can play a major role going forward in reform. This is one of the great dramas in American political life at the moment. This highly skilled political operative has had the major crisis of his career, precipitated by a police killing of a black teenager. I’m not making a point about the mayor’s character. I don’t know his mind, I don’t know his motivations. But his circumstances are such that the only way for him to recover his political viability and to protect his hope for a legacy is to do the right thing on police reform.

So I think it’s important that the feds come in. I hope it’s a limited intervention, that doesn’t preempt and shut down community processes as sometimes happens when the feds come. But I think it’s a distraction to call for the mayor’s resignation. I think it’s important to keep constant and sustained pressure on him to advance the process of real, enduring reform. Not just scandal management, but real reform.

This has surely moved to the very top of his agenda, and I think that’s important. It’s part of this extraordinary moment we’re living through. We’ll see what happens. But I think if he can rise to the occasion and bring his political skills to bear, we could see the sort of police reform that people have been advocating for and aspiring to for generations.

All of us need to be worthy of this moment, worthy of this opportunity. We’re talking here about saving lives. We’re talking about ensuring public safety and neighborhoods that are, at least in relation to the police, like failed states where people have to figure out how to protect themselves. The stakes are really high at the moment.

CM: Jamie, it’s been a pleasure having you on the show. I really appreciate it.

JK: Delighted.