AntiNote: Alexandra recounts her visit to an Athens squat with a women_*’s floor, her experiences and conversations with refugee women_* in Idomeni, and what flight can mean for women_*. Alexandra is an activist from Zurich involved with various autonomous women_*’s spaces such as the Woman_* Bar in the Kernstrasse autonomous center, as well as with queer/feminist women_*’s groups.

We are grateful to Alexandra for this important text, which first appeared in German in the 4 March 2016 print edition of Vorwärts (Zurich). We extend our gratitude as well to Chloe Kritharas Devienne for her photographs.

(deutsche Originalversion ist hier einzusehen)

A group of women_* are sitting in the living room of a squat. There is coffee, tea, dumpstered cake and pistachios. The room is full; we sit on the floor and on sofas made homey with blankets, getting comfortable. There is a lively discussion taking place about how the new anarch_a-feminist group should best present itself on a compositional floorplan of the house, summed up in two sentences (“Is it necessary to explain the term ‘anarch_a-feminist group’ more precisely? Or is it already clear from the name that the women_*’s floor is open for people who live outside of the gender binary?”). Yesterday there was an unpleasant incident because someone had drunkenly overstepped boundaries. This is also discussed, and there is a lot of laughter as well as earnest listening; everything as it always is when anarch_a-feminists gather.

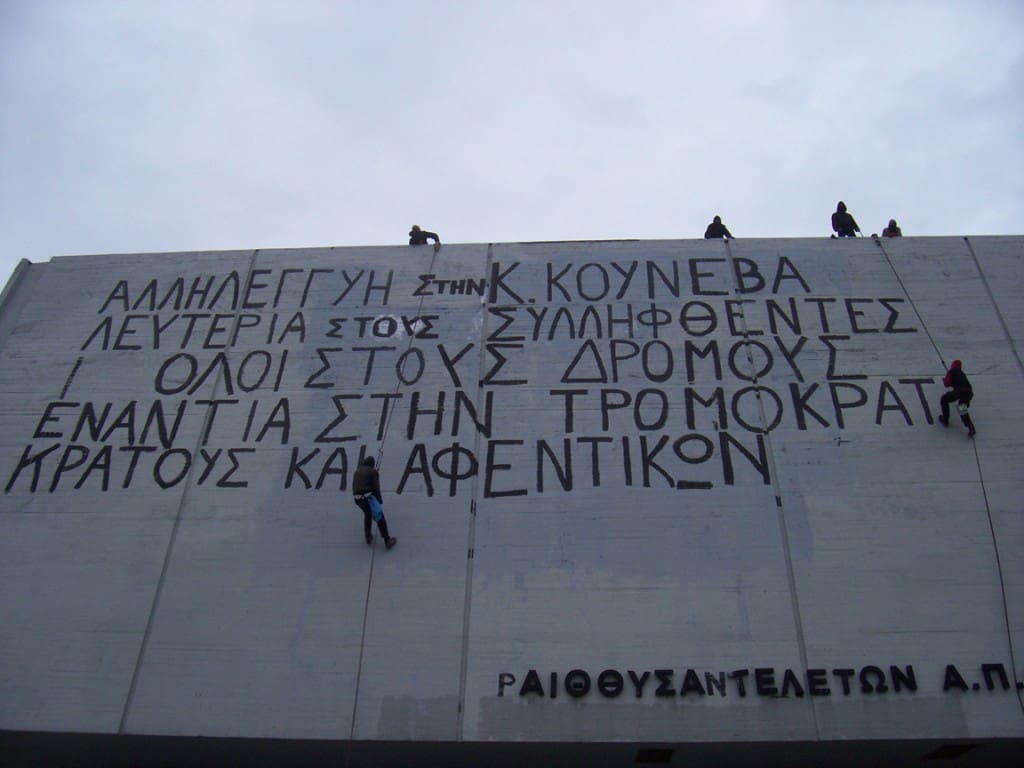

Well, not entirely everything. The squat is located in Athens’ Exarchia neighborhood, and was occupied a month ago with the intention of offering a space for people both with and without documents who have been stranded in Athens on their way to western Europe and would otherwise be living on the streets—a self-organized anarchist space for refugees and their supporters. The house has several floors, and room for around fifty refugees and activists to live and sleep. In a lower floor there is a large kitchen and a common room where, every evening, everyone gathers, cooks, and eats together.

There is a free store, a resource center with information about the asylum process in Greece as well as about onward travel, and there are showers. The house is lived in and maintained by people both with and without papers—what is special about it is that an entire floor is designated as a women_*’s space, where women_* with and without legal residence status live together. The other women_* at the meeting tell me that this is new for Greece, and that it feels liberating.

The women_*’s meeting is vividly mixed: women_* from lesbian groups, queer and trans activists, migrant women_*, and women_* who have never heard the word anarch_a-feminist before; women_* who are looking first and foremost for a place to sleep, and women_* who have for years been part of Greece’s strong, militant anarchist movement.

I am sitting somewhat in the middle, and I am trying to translate for Sara, a woman_* from Morocco, what someone just said about how it is important that this space be open for trans people and people who live beyond gender normativity. I am a little overwhelmed. How do I describe this to Sara, first of all in French, and second of all in simple, clear words, without losing complexity? I falter—but am pleased when she says, “Oh, it’s not necessary to decide if you are a man or a woman, you can be somewhere in between.” Yes, that’s basically what we mean.

An open, non-hierarchical space welcoming the participation of all women_* is a major challenge in this context of different lived realities crashing together. It takes constant examination of our own privileges and socialization, and much explaining of what we mean by things—both extremely important activities for which barely anyone has time because of the immediate demands of the overall living situation, but without which nothing would work.

My way here took me through Croatia, Serbia, and Macedonia to the border town of Idomeni, Greece, where I stayed for four weeks. This evening in Athens is my last after five weeks in the Balkans.

On the border in Idomeni

Anywhere from six hundred to five thousand people arrive in Idomeni every day, wanting to cross the border into Macedonia. Since this option has been repeatedly restricted—first to people from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan; then to only people from Syria and Iraq [and ultimately, since the time of writing, to no one at all]—the situation for people from other countries (mostly Iran, Morocco, or Pakistan) is especially difficult and precarious. They are stuck at the border, living in the forest, looking for ways to get across, only then to begin the six- to ten-day march to Serbia. It is yet another enforced stop on their long journey to western Europe in which they experience yet more police violence, cold, hunger, lack of information, and great hopelessness.

Our support is barely more than a tiny drop in the ocean, but it does make it possible for some to carry on their struggle and their flight—their flight to an even more uncertain future in western Europe. The opening and closing of the border—as well as the sorting and re-sorting of people into categories determining who can and cannot legally cross—occur from time to time, usually arbitrarily. There are strict document checks, language checks, and a long survey with exactly three correct answers. Therefore even people who could theoretically pass the border often get stuck in camp at Idomeni or a gas station in the middle of nowhere, for days on end.

For months now, autonomous groups have attended to the distribution of clothing, tea, food, and information—as well as observing and documenting the practices of the border police—at the gas station, in camp, and in the forest. The volunteers themselves are increasingly criminalized by the Greek state and constrained in their work, facing regular identity checks, house searches, and surveillance. The feeling is palpable there that the borders of Fortress Europe are becoming increasingly impassable. But what does this mean for women_* in particular?

Women in Flight

Among the fleeing are ever-increasing numbers of women_*. According to the UNHCR’s figures from the end of January 2016, over sixty percent of the people arriving on the Greek islands are women_* and children. Last summer it was only thirty percent—this is a monumental increase in the numbers of women_* risking the dangerous journey to western Europe, often with their children.

Flight holds a different set of dangers and realities for women_*. This is not much talked about, and even less written about. In the course of the last few weeks I have had many conversations with women_* in Serbia as well as in Greece, both in Idomeni and in Athens. The stories always resemble one another. Women_* tell of violence, sexual assault, and fear. They get threatened and attacked by fellow travelers, the police, smugglers, and their own families.

At the same time they are burdened with great responsibility, as they are frequently solely responsible for children and also carry all the family’s valuables and money, since it is believed that it is safer with women_*. Aysha told me at the MSF camp in Idomeni that she did not feel safe there, because she had to sleep sharing a large tent with many men. She reported having woken up many times during the night with a hand on her breast, and having been harassed by strange men while going to the toilet at night. She commented, almost excusingly: “But why should it be any different here than where I come from or anywhere else in the world?”

I thought to myself, she’s right. Structural violence against women_* is a part of our reality, part and parcel of our patriarchal world. Nonetheless, the situation of refugee women_* is more fraught with oppressive structures and threats than my privileged situation is. Refugee women_* find themselves facing the difficult choice, for example, of either making themselves more vulnerable to (sexual) violence by traveling alone or in groups of exclusively women_*; or attaching themselves to men—who can “protect” them but who can also exercise a lot of power, which can lead to more (sexual) violence and oppression.

Either way they are not safe, and therefore suffer that much more severely from the strains of fleeing, because they barely sleep, are constantly looking after children, and have to remain in a 24/7 state of alert in order to protect themselves.

Women_* who have neither Iraqi nor Syrian papers and therefore cannot travel the state-approved corridor—instead getting systematically sent back from borders, arrested, and possibly even expelled—experience this reality even more acutely.

Smugglers repeatedly blackmail these illegalized women_* into sex—either offering to reduce the price of the journey, threatening to cut the journey short, or simply taking advantage of the power they hold over them. Many illegalized women_* are forced to sleep on the street, not a safe place, and if they get picked up by police they are confronted with yet more violence, robbed and beaten. Many of these women_* are pregnant. Making matters worse, women_* make up only a small proportion overall of the illegalized refugees, which makes it nearly impossible for them to defend themselves collectively or protect one another.

For these reasons, structures like the women_*’s space at this squat in Athens are so important. They offer women_* the chance to compare notes and talk openly about experiences of violence, and provide a safe place where they can get some measure of peace and quiet. In certain ways, it doesn’t make much difference if the women_* have documents or not or if they are activists or refugees.

We share experiences of violence, though they might vary in severity as well as frequency; we share anger at oppression and powerlessness under patriarchal structures, and we share the solidarity that we have for one another. This gives me renewed energy to keep fighting—for myself and together with women_* in flight.

If you too would like to get to work in Greece building women_*’s structures or would like to support existing women_*’s spaces in Athens or Idomeni financially, please write to alexandra[at]ungehorsam[dot]ch; I would be happy to put you in touch with women_* in either place.

THE WORD WOMEN_* IS WRITTEN THUS IN ORDER TO DEMONSTRATE THAT IT IS A WORD DESCRIBING A SOCIAL CONSTRUCT; AND THAT THE AUTHOR LIVES THE IDEAL THAT WE MUST LET GO OF THE GENDER BINARY AND THE PATRIARCHAL STRUCTURES THAT COME WITH IT.

Translated by Antidote