Transcribed from the 5 June 2016 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

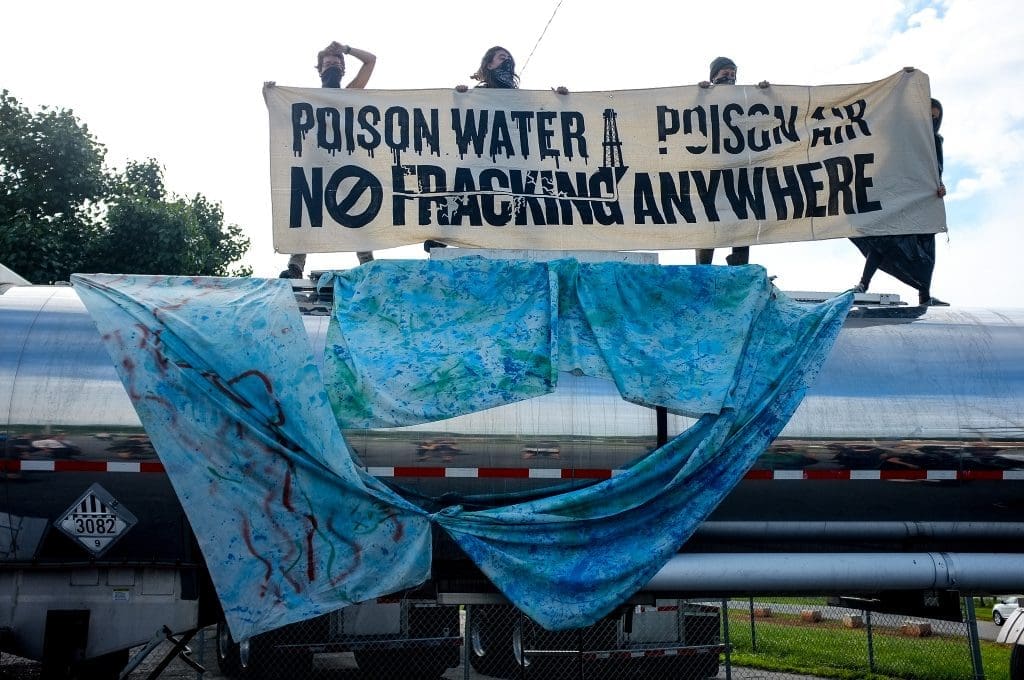

People are tired of these extractive industries coming into their communities, taking out the resource wealth, and leaving them a “sacrifice zone.” That’s what fracking really does. It takes these bucolic rural areas and makes them into an industrial work site, and it leaves people devastated.

Chuck Mertz: Why is fracking so universally supported by politicians on both sides of the aisle? Why, in our bid to fight climate change, is the US government and its elected leaders so enamored with burning a fossil fuel like natural gas, when you consider everything that goes into its extraction, production and distribution may actually be worse for the environment than coal?

I have no idea. But our next guest does. Returning to This is Hell!, Wenonah Hauter is author of the new book Frackopoly: The Battle for the Future of Energy and the Environment.

Welcome back to This is Hell!, Wenonah.

Wenonah Hauter: Hi, I’m so glad to be here.

CM: So, at the front of your book there’s this beautifully weird, web-like schematic showing connections between not only finance corporations and utilities to fracking, but also nonprofits and even the media. How are the Nature Conservancy and Walt Disney connected to fracking?

WH: What we see is an interlocking board of directorships, where the largest institutions work together to promote the status quo. It gets interesting when we start looking at groups that are supposed to be protecting the environment, and find how they’re connected to the finance industry.

In reference to the Nature Conservancy, there is fracking taking place on some of the land that they’ve “conserved.” But what we see in the schematic is that over the last hundred years plus, the rules have been changed—because of the power of the oil and gas industries—to allow a giant monopoly which doesn’t provide us information about the most important issues of the day.

The fact that in 1983 we had fifty different major media outlets and today we have about six shows why there’s been such a blackout of information on what’s really going on with climate change and with fracking.

CM: So in a bigger sense, is this about the interconnectedness of all these industries and their ability to impose whatever decision they want upon the public? Is this more about this web of power over all else, even those who are elected? A conglomeration of wealth that is determining our policies and our way forward?

WH: Yes, absolutely. In Frackopoly, I tell about the epic battle that’s taken place over the last hundred years. Most people think that the word monopoly is an old word, and we don’t have to deal with that kind of structure any longer. But over this time period the oil and gas industries either skirted the law—or conspired to break the law—and then helped put into power president Ronald Reagan, who eviscerated antitrust law, changed the definition of it, and since that time we’ve seen every industry—but especially the oil and gas industries—really consolidate.

A very few major players have been able to rewrite our laws to influence our politicians. Much of the leadership of the Democratic Party is just as in bed with these economic interests as is the Republican Party. That’s why it’s so important that there’s a huge movement growing to stop fracking, to keep fossil fuels in the ground. And that’s why you have seen fracking become an issue in this presidential campaign, because people are wising up.

CM: But isn’t natural gas, like Hillary Clinton says, a “bridge fuel” away from coal and oil and onto cleaner energy?

WH: I’ve been working on energy for almost forty years. We’ve been hearing that natural gas is a “bridge fuel” for at least 25 of those years. The fact is, natural gas is a bridge to disaster. In the short term, methane (and natural gas is methane) is at least 87 times more potent as a greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide over the first twenty years after it is emitted. There’s a lot of scientific research on that now.

We need to take dramatic action to stop emitting greenhouse gases over the next ten years. Methane emissions are, in the short term, more dangerous than carbon emissions. And we’ve just seen the Obama Administration come out with some draft rules around methane, but they actually grandfather in all of the existing infrastructure, including 140,000 wells that have been fracked and are continuing to produce gas and oil.

The other thing that we need to understand is that throughout the production cycle—drilling, fracking, processing, transporting gas—there are major leaks which the EPA has under-counted.

And the last point I’ll make is this: why would we be building and investing billions of dollars in the infrastructure for another forty years of natural gas, if it were a “bridge fuel?” This is really about dying industry, the oil and gas industry, that is willing to wreck our climate to keep producing gas and oil.

And by the way, over the last several years, eighty percent of fracking has been for oil, not natural gas.

CM: So is the problem fracking itself? Or is the problem using another fossil fuel? What is the bigger problem here? Is it the process as well as the outcome that’s the problem?

WH: It’s the process, too. I don’t want to discount the seventeen million people who live within a mile of a fracked well, and the horrible suffering that is going on in these “sacrifice communities” where their water is polluted, their air is polluted, and they’re living with major disruption from industrial traffic: thousands of truckloads of material is necessary to drill one well.

The process itself is very damaging. It employs these science-fiction-like technologies where drillers inject literally millions of gallons of water, dangerous chemicals, and sand into the ground, under extreme pressure, to extract the oil and natural gas. They use about fifty times more water than conventional drilling for oil. And after they drill this deep vertical well a mile or two miles under the ground, then the fracking takes place in several stages along a tunnel that is several inches wide that runs horizontally for another mile or two. That breaks up the shale formations and releases the gas and oil.

The incredible depth at which this all takes place means it’s really impossible to know all of the unintended consequences. And then: coming out of these wells, every day, is on average about 10.5 billion gallons of toxic wastewater. One of the ways that this wastewater is dealt with is it’s injected deep, deep underground, and that’s what’s causing the flurry of earthquakes in places like Oklahoma, Ohio, and other fracked states.

CM: How much do you think those “frack-quakes” (as they’re called) are leading to the renewed and invigorated anti-fracking movement? Do you think that that was the problem that broke the public’s back when it came to issues over fracking?

WH: It depends where you live. My organization, Food and Water Watch, did a lot of work early on; we were the first national group to come out and call for a ban on fracking, in 2011. And there were literally hundreds of grassroots groups around the country, especially in states like New York and Pennsylvania, that were already calling for a ban on fracking, because they saw what was happening, all of the problems, and they were just outraged.

I think people are tired of these extractive industries coming into their communities, taking out the resource wealth, and leaving them a “sacrifice zone.” That’s what fracking really does. It takes these bucolic rural areas and makes them into an industrial work site, and it leaves people devastated. Their property is worthless. That has created a major movement.

There’s another movement now, happening in urban areas like LA, because there’s fracking and drilling going on in the city of LA. There’s fracking going on in the Central Valley of California, where there’s a drought. Some of that wastewater is being used to water food crops. This isn’t something I’m making up. This has been covered in the LA Times.

So there are a lot of issues, especially on top of the droughts that we’re seeing in some areas. A lot of the areas in Texas and the West where fracking is taking place are very, very dry, and frackers are competing with agriculture for water.

Spills and accidents happen constantly all over the country. It’s part of what the industry considers the cost of doing business. The oil and gas industry has always had a lot of accidents. But nobody except alternative media sources really connects the dots about all of the accidents, all of the pollution.

CM: You were just mentioning how money is taken out of the local economy. There were a lot of articles written about the huge boom that was taking place in the Bakken fields in North Dakota. There have been articles about a boom town by the name of Williston, North Dakota, where they went through boom times, then they went through bust times, and now they’re just back to being the small town that they were before.

But you say that frackers take money out and then they leave a legacy of problems behind. So are there people, or business concerns, maybe, within these fracked communities that do want fracking to take place, because of all of the indirect ways in which the community might make money?

WH: One of the problems in our society, especially because so much media coverage is so poor on this issue, is that people have a short memory about booms and busts. The oil and gas industry’s history over a hundred years, really, is about booms and busts. They go into an area, and a lot of people come. That’s what happened in North Dakota. The population surges. A lot of local business leaders do begin to make money, but it also pulls a lot of money out of the community, because they have to build improved roads; there’s a lot of damage that has to be paid for out of tax money.

Some people make a lot of money, but a lot of other people have to live with all of the suffering and the changes in their community. And those changes aren’t always things that one would necessarily think of right off the bat. A lot of young men move into these communities to do the hard labor. They’re called roughnecks. They’ll have a lot of money in their pocket, work long hours, there’s not much entertainment, and there ends up being a lot of drinking; a lot of new bars sprout up. It becomes more dangerous for women: we’ve seen, in some communities, statistics showing more venereal disease and more crime.

So there are a lot of impacts in these communities, and then when the bust comes, the local people who have invested a lot of money to build infrastructure—whether it’s restaurants or the man-camps where the workers live—lose a lot of money. It’s not a long-term rosy picture.

It’s not a way for a community to do local economic development. That would take a lot of policy changes and a real commitment to a future with energy efficiency and renewable energy. A lot of those jobs, making our communities actually energy efficient, would be longer lasting.

CM: You write about thousands of leaks, blowouts and spills from the industry that involve these extremely hazardous wastes. How little are these reported? The media doesn’t have the greatest record when it comes to prioritizing environmental messes. For instance, back in mid-May, an oil spill from Royal Dutch Shell’s offshore “Brutus” platform released 2,100 barrels of crude, around 90,000 gallons, into the US Gulf of Mexico. That’s simply not a big enough spill to get media attention anymore.

WH: The problem is that spills and accidents happen constantly all over the country. It’s part of what the industry considers the cost of doing business. The oil and gas industry has always had a lot of accidents, and worker deaths. It’s a very dangerous industry to work in. But nobody except alternative media sources really connects the dots about all of the accidents, all of the pollution.

And then we see government agencies like the EPA not really doing their job, because they’re terrified. The political appointees are terrified. A few years ago there were three very important investigations of water pollution underway: in Dimock, Pennsylvania; Pavillion, Wyoming; and Parker County, Texas. All three were shut down because of political pressure.

The EPA started this study a few years ago, seriously looking at water pollution. The scope of the study was narrowed; there was criticism from scientists about how the study was designed; and when the study came out the headline was basically, “No Water Pollution.” But when we went through the hundreds of pages, there were many instances of water pollution. And in fact now the advisory committee overseeing the EPA’s work on this study has had several meetings about how the EPA did not do its job and did not tell the truth. We’re hoping to get some justice at the EPA.

The Obama Administration has had very close ties to the industry. The most recent energy secretary, Ernest Moniz, has very close ties with the industry, and has claimed he hasn’t seen any evidence of fracking per se contaminating groundwater, and that the environmental footprint is “manageable.” The interior secretary, Sally Jewell, has actually bragged about fracking wells in her prior career in the industry, and says that it’s an important tool in the toolbox for oil and gas.

It’s been a long story of the EPA ignoring and burying findings, and we have to do a better job holding our elected leaders accountable.

CM: You are also critical of the privatization of utilities. It was all going to lead to more efficiency and less cost, as we wouldn’t have to foot the bill through taxes. Has the privatization of electric utilities led to more choices, better service, lower prices, and overall lower costs because of a cut in taxes and government’s bloated bills?

WH: No. There was a lot of confusion in the mid-1990s among many environmentalists who ended up signing off on the deregulation of electricity, both at the wholesale level and, in some states, at the retail level. Doing away with the regulations around the sale of wholesale electricity has meant that there’s a whole lot more electricity being generated today (and only a small percentage is being generated from wind and solar energy—just over five percent).

Because of other major changes in federal law, in 2005 the rules were changed around how electric utilities can operate, and today we have giant electric utilities like Exelon (which is a behemoth that now operates in about thirty states). It’s really the deregulation of electricity, and the removal of a federal protective law that was passed in the 1930s, that has allowed companies like Exelon to dominate the electricity industry.

We have about twenty electric companies that are so large that they produce more than fifty percent of the energy that’s used in this country. And they gamble in energy futures and derivatives; they’re into all sorts of other kinds of businesses, and it’s simply about being extremely profitable and draining the resources out of these communities. It’s not about having good service or moving into a renewable future. It’s about maintaining the status quo and making as much money as possible.

Why would we put the financial services industry in charge of the environment, especially with all of the gambling that we’ve seen in recent times and how it collapsed our economy? We should work to ban fossil fuels, not to have measures using the market. If we’re going to fight for something hard, we should fight to keep fossil fuels in the ground. We need to make it politically acceptable to say this.

CM: You write, “Unfortunately, while renewable power is growing, natural gas generation is growing much faster at the same time that coal-generated electricity is declining.” So is fossil fuel use growing more than renewable energy use?

WH: What’s happened is that because of electricity deregulation, coal and natural gas have continued to grow. But coal is a special case. Right after deregulation in the 1990s, a lot of old coal plants were taken out of mothball, and were generating a lot of energy. And then a lot of the rules were changed to begin to take coal back out of production, so it’s declining. It was about 33% of our energy mix last year.

On the other hand, natural gas was incentivized at the same time, because of deregulation: all these merchant plants are no longer actually connected to providing electricity service to a customer, but are just producing electricity and trying to sell it. Small gas-fired plants are perfect for that market, especially since the rules have been written to incentivize them.

In 1990 we saw about eleven percent of our electricity produced from natural gas. In 2015 it was 32.7%, about the same as coal, and it’s predicted to continue to grow, unless we change the rules. But Obama’s clean power plan incentivizes the use of gas, because it’s focused on carbon, and of course burning natural gas produces less carbon dioxide. But in the shorter term, all this release of methane—because methane is a more potent greenhouse gas—is actually worsening climate change.

So that’s the sad story. Renewables are growing, but not fast enough. We’re going to have to change the policies to stop incentivizing natural gas, to stop all of these approvals for building the new infrastructure—tens of thousands of miles of new pipeline. In fact, since natural gas was deregulated in the late 1970s and 1980s, which we haven’t really talked about, we’ve seen more than 900,000 miles of natural gas pipelines built. Today we have about 2.5 million miles of gas pipelines in this country, enough to go around the Earth a hundred times, and there are many, many more being built, along with processing facilities. In the northeast, for instance, they’re building pipelines into areas that don’t use natural gas for heating.

It’s all about using more natural gas rather than moving into renewables. We have to get together and start putting in place the policies that are going to move us into that renewable future, not into this continued fossil fuel future that’s going to lead us down a road to a burning planet.

CM: You write, “It is time for the major green groups to fight for a transition to real sources of renewable energy and energy efficiency, not to depend on market-based schemes with no track record of working.”

What major green groups have yet to join the fight against climate change?

WH: In the book, I write a chapter about the Environmental Defense Fund, because no group has run interference for the industry more than EDF. And it’s been frowned upon, in my entire career in the environmental movement, to say anything negative about another environmental group. But some of the things that EDF has done actually make them more of an industry group than an environmental group.

That’s why I take a chapter to look at the history of how the president of the organization, Fred Krupp, was recruited during the H. W. Bush Administration to get on the bandwagon about trading. In that case it was for the Clean Air Act around ozone emissions and acid rain. When you really look at the data, there’s no proof that acid rain was actually reduced from this trading. It probably would have been lowered anyway because of some of the new technologies.

What’s happened since that time is that the EDF has led the drive to use the market rather than to have laws and protective measures in place. In fact, they’re one of the groups that’s now promoting water pollution trading, which has a whole other set of problems. And they’ve been very involved, over the past three decades, in promoting the use of natural gas and making it something in the environmental movement that’s seen as the “responsible” position to move us into a renewable energy future.

I just think it’s time to put aside the nonsense. If we’re really going to put together a movement to fight for something, why would we fight for these schemes? Why would we put the financial services industry in charge of the environment, especially with all of the gambling that we’ve seen in recent times and how it collapsed our economy? We should be putting into place rules and regulations on a range of environmental issues. We should work to ban fossil fuels, not to have all of these different measures using the market.

I’m even doubtful that carbon taxes are the way to go. Look at who’s promoting carbon taxes: Exxon has said that they’re comfortable with carbon taxes. Because they’re just going to pass the cost on to consumers.

If we’re going to fight for something hard, we should fight to keep fossil fuels in the ground, and we need to make it politically acceptable to say this. That’s what we did at Food and Water Watch with banning fracking, when we helped kick off a national movement by working shoulder to shoulder with all the brave grassroots groups, groups all across the country that were fighting for a ban.

CM: You write how “some green groups claimed if electricity were deregulated, renewables would thrive and nuclear plants would be retired. But a close examination of the numbers shows that this has never happened.”

So why aren’t we demanding this in the deregulated market? Is this all our fault as consumers for not demanding more of the market? And are we all, in that sense, still in climate change denial?

WH: First of all I think it’s part of the mythology that consumer choice is going to be a way to a renewable energy future. What we need is for people, rather than being consumers, to be engaged with public policy and to fight to hold their elected leaders accountable. That’s what’s going to take us to a renewable energy future. It’s going to demand collective action.

There is an inattention to our civic duties because people are too busy; they are not encouraged through our means of communication to be involved with politics and policy any longer. It’s our job as activists to get the measure out that we can make a difference. We can ban fracking in states like New York, and have a moratorium in Maryland, and have more than five hundred communities across the country that have taken action against fracking.

But it’s going to take people getting involved. It doesn’t take everybody, but it takes a group of committed people to do that. And that’s why I’m so excited about the future, because I see a lot of young people who are interested in challenging the status quo and fighting for the future that they want and that we all want for our children and grandchildren.

CM: Thank you very much, Wenonah, for returning to This is Hell!

WH: Thanks so much for having me.

Featured image source: Piedmont Earth First!