Transcribed from the 16 July 2016 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

The end point of Trump is not simply antipolitics. The end point of Trump is concentration camps. That’s something we cannot forget.

Chuck Mertz: With the amount of hate we hear spewed by our media and politicians, and the staggering toll violence has taken on our society, is it any wonder that we end up with candidates for president like Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump? Here to give us his take on US politics as we head into the two major parties’ political conventions: educator, scholar, public intellectual, and cultural critic Henry A. Giroux.

Henry, great to have you back on This is Hell!.

Henry Giroux: Hi! Great to be back, Chuck.

CM: Henry’s most recent writing includes Antipolitics and the Plague of Disorientation: Welcome to the Age of Trump. Henry’s most recent book is America’s Addiction to Terrorism, but he has a new book being published in early September, so I’m betting he’s going to be back on This is Hell! real soon; the name of that book is America at War with Itself.

In an email you sent me this week, Henry, you wrote, “At one level there is, and rightly so, a lot of talk about the violence waged against the police and the police violence waged against poor blacks who live in America’s war zones. Yet nothing is said about either the wider backdrop of violence that fuels a national election or the deep roots it has in the torture, lynching, maiming, and crippling of millions of ungrieved bodies.”

How much do you believe violence defines the United States today?

HG: It is the central organizing principle of American culture and American society. It touches everything. It touches sports, it touches entertainment. It’s deeply embedded. It’s legitimized; the police can act with impunity; Barack Obama can kill people indiscriminately with drones and claim it’s justified. It is present in an economic system that corrupts everything it touches and causes enormous, widespread misery. It’s deeply embedded in our school systems, which now look more like prisons than schools. It’s deeply embedded in a mass incarceration system that now has become the default welfare system for blacks.

It’s difficult to get away from. It seems to mediate everything that we touch, and it seems to generate a kind of historical and social amnesia. We have no understanding of the historical narratives that produce it (and that have gained momentum in the current moment). And we have no understanding of how to take isolated issues of violence and relate them to a broader theoretical and political understanding of what that violence is about and how it gets legitimated, produced, and used.

CM: You write about a “discourse of hate that is normalized by the Republican Party and covered up by the Democratic Party.” So hate and violence is not a partisan issue; it is bipartisan. How does the Democratic Party cover up the discourse of hate?

HG: It covers it up by making the claim that it cares about working class people, while it’s in bed with the lobbyists of the financial state. It covers it up by supporting a neoliberal system that causes enormous misery for workers, for people in unions, for educators. Think about Obama and this embarrassing discourse of hope that he started, which really became a discourse of hopelessness. Think about his educational policies; think about his wars abroad. Think about one trillion dollars being allocated to upgrade the nuclear arsenals. Think about the disposability that goes on in the United States. He has expelled more immigrants than any other president in history.

We have a party that looks at Trump and says, “Oh my god! Trump is so dangerous! Look how irrational he is! Look how emotional he is!” and at the same time, under the banner of reason, the policies they implement, and the social misery and the energies of death that they mobilize, the zones of abandonment that they produce, are just mind-boggling.

The Democratic Party wraps itself in a weak appeal to the social contract, and at the same time presides over a country in which massive inequality has reached proportions unknown to the human imagination. It’s really difficult to not recognize that they are a bit more than simply complicit.

CM: You were saying that the Obama administration has deported more people than any other administration in US history. Do you think that the Democratic Party turns a blind eye to the inherent racism that fuels anti-immigration sentiment not only here in the United States but overseas as well?

HG: They make gestures towards what it might mean to control it. But at the same time, they simply don’t implement the measures that would address the problem. The Obama Administration plays both sides of the coin. At one level there’s rhetoric that says we need to do something that will address the issue. But they compromise. This is the party of utter compromise, and they compromise with the right.

Whenever I hear the Democratic Party speak about justice, about the social contract, about what it might mean to address the needs of minorities, it makes my head spin. Because it never gets to the heart of the problem. It never says we need to abolish the mass incarceration state. It never says the problem with police violence is not simply about the police, it’s about a culture of violence. It never says we live in an economic system that is so unequal and so death-oriented, so abusive in what it does to most people in the United States, that it really has to be changed.

What they say is, “Well, maybe we need to tax corporations a little bit more.” They don’t talk about redistribution of wealth. They talk about modifying, in a very minor way, the power that’s already in place. They’re not talking about changing the system. They’re talking about strengthening the system by leading people to believe that they really want to change it.

CM: Does the contradictory nature of a rhetoric that’s undermined by compromise lead voters (and non-voters) to believe that government simply can’t ‘get the job done?’

HG: It leads people to believe that politics doesn’t work anymore. It leads people to believe that they’re being written out of the script. So we turn to saviors, we turn to heroes. We turn to people who mobilize hate. We turn to the strong man. We turn to people who claim, “I’m going to make it easier; I’m going to make it simple for you. You don’t have to think about this. Just follow me.”

This is not a new script. This is a very old script. We saw it in Argentina, we saw it in Italy, we saw it in Germany. The United States is now facing a moment in its history that’s the most dangerous moment it has faced since the Civil War. This country is on the verge of fascism. What is so startling about this is the spinelessness of liberals who support this crap, who will say things like “Well, he’s not that bad. There are certain economic measures, like he’s against the TPP.” Look, this guy’s a fascist. He wants to energize and mobilize violence against dissidents. He wants to build a wall. He wants to deport eleven million people. What do you think is going to happen when he becomes the president of the United States?

How is it we can wipe out whole segments of the American public and say that they don’t count anymore, and have four hundred families control half the wealth in the United States? That’s fascism already. That’s fascism with a different face.

What is the United States going to look like? What is dissent going to look like? What is the use of force going to look like? What is the military industrial complex going to look like? What is foreign policy going to look like, now that it will be mobilized by a hysterical militarist? It’s frightening. And yet, I read a piece in the New York Times last week, by Sam Tanenhaus, saying he’s not that bad! Maybe he can help the Republican Party be more conscious about what it’s doing! Maybe he can implement reforms that Republicans haven’t thought about!

Honestly, I want to throw up. I read that stuff, and I think reason has just gone out the window, and liberals are going to find themselves, in about five years, with a knock on their door, and they’re going to be in jail. The end point of Trump is not simply antipolitics. The end point of Trump is concentration camps. That’s something we cannot forget.

CM: Do you believe that all of his supposed policies are a distraction from his key, core belief: racism?

HG: I think it’s absolutely right. All this stuff about how he’s going to lift the working class up, he’s going to save jobs, look at his tax reform policy, he’s going to do this and that for working class people…it’s nonsense.

Trump is the embodiment of a financial elite who will lie, who will mobilize emotion over reason, who will scapegoat and demonize, who will say things like “We’re really angry!” (of course people are angry!). And then he tells them they should be angry at blacks. They should be angry at Mexicans. They should be angry at the Chinese. But they shouldn’t be angry at Putin. They shouldn’t be angry at Saddam Hussein! After all, as he said, “He kept people in check.”

This guy is a nightmare. He’s like some kind of historical fiction that appears on your screen for thirty minutes, and you think, wow, is that possible? Could they really create a program that bad? That horrifying, that terrifying? He’s terrifying. In light of his fascist ideology, to believe for one minute that Trump is going to implement policies that are going to somehow extend the promise and the ideals of democracy—particularly economic democracy—while at the same time violating every principle of justice…that’s hallucinatory to me.

CM: You write, “Unfortunately, recognizing the United States is about to tip over the edge of the abyss of authoritarianism isn’t enough. There is a need to understand the context—historical, cultural, political, and economic—that has created this moment in US society in which fascism becomes an end point. Trump is only symptomatic of the problem. Condemning him exclusively does nothing to contain it.”

So is Trump, then, not an outlier? Because a lot of people think if you defeat Trump, you defeat the Trumpism within the Republican Party right now.

HG: That’s a fabulous question. The notion that if Trump is defeated, we’ve won…the real question is not whether Trump gets defeated, but what the forces are that produced him. How have they been sustained over the last thirty years? What about the discourse of racism that we saw in Reagan and Nixon? What about the War on Drugs? What about the increasing rise of a neoliberal policy that has no concern for human or social cost whatsoever? One that separates economic activity from social costs? What about the corruption of politics? What about the takeover of the mainstream media by corporations? What about the increasing attempts to eliminate dissent? What about the takeover of the cultural apparatus and the turning of investigative journalism into simply entertainment, being held up by a celebrity culture in which idiocy becomes more important than literacy? What about the collapse of civic literacy in society? What about the collapse of public culture and public goods? The public sphere?

These are the issues that we have to trace. We have to ask ourselves how this happened. What kind of ideology was put in place to legitimate this? How was it spread? How was it defined? What kind of institutions supported it? Who are the people who benefit? Who are the people who live off the energies of the dead, feeding off people who are no longer worried about getting ahead but are now just worried about survival? How is it that questions of disposability became so widespread that the word disposability no longer speaks only to the margins of society but now speaks to workers, to teachers, to public servants, to the middle class?

How is it we can wipe out whole segments of the American public and say that they don’t count anymore, and have four hundred families control half the wealth in the United States? That’s fascism already. That’s fascism with a different face. That’s a fascism that is subtle in its claim that it isn’t fascism, because it makes a claim to being democratic. It’s emptied out politics by removing two things: any form of ideological substance, and the opposition that might be able to challenge it.

CM: How key is the loss of public space, with traditionally public goods being sold off to the private sector?

HG: It’s central. Look, public space provides the language. It provides the opportunities, it provides the inspirations, it provides the energies for people to define themselves as something other than consumers. It talks about justice. It gives some legitimacy to the notion that empathy matters. It makes the suggestion that we can’t live alone, that the emphasis on self-interest and radical individualism, this cage culture that we have created, this reality TV in which there’s only one person left on the island—that this is a form of social poison. It kills the notion of the social.

The public sphere resurrects the social. It inspires it with a democratic dream and a promise about justice, about equality, about providing for people, giving them a sense of agency, and talking about choice without the kinds of constraints that make choice a silly and ideologically propagandistic term. Sure, we have “choices.” But you can’t talk about choices without constraints. What the hell kind of choices do you have if you’re poor? What kind of choices do you have if you can barely feed your children? What kind of choice do you have when your choice is the choice between taking medicine and buying food?

CM: You also write, “When the mainstream media can write and air allegedly objective stories about a candidate who is a fascist, who delights white nationalists and neo-Nazis, without highlighting that he advocates policies that are racist, constitute war crimes, and if elected will throw the world into chaos, this suggests that America has forgotten what it should be ashamed of. It means that collective morality and the ethical imagination no longer matter.”

What do you mean by the collective morality and ethical imagination?

Rather than bewailing what Hillary will inevitably do, let’s get real. Let’s build the institutions, let’s build the movements. Let’s stop fragmenting the left. Let’s get together and see this as an enormous opportunity to redefine the meaning of politics. Let’s get radical.

HG: The question of ethics itself has been relegated to the dustbin of history. We find ourselves working within an ideology now that says there is no correlation between any kind of activity and the social cost that it produces; that we don’t care about what the consequences are, because morality doesn’t matter anymore. Morality doesn’t add up in the increased profit motive, so let’s get rid of it. Social responsibility is seen as a burden. People who claim that they care about other people, people who claim that we should be concerned about the consequences of our actions, that human beings and their well-being should be the end point of how we think about how a society is constructed—those things are seen as a pathology.

The Republicans in particular have created a whole vocabulary to expel the notion of social responsibility from the world of political discourse. They call people who are poor “moochers.” They say that workers and people who are part of unions only do this to benefit their own self-interest. They claim that any time people work together, that’s a sign of weakness. And in Ayn Rand fashion, they make the claim that the only thing that matters is to be strong, powerful, and indifferent to any sense of justice.

When we talk about the question of morality and about the radical imagination, and social justice—this is a discourse in decline. Because the public institutions and the public spheres that have always legitimated it—and made it matter, and instilled in generation after generation its political and moral currency—are in decline.

We don’t talk now about what the obligations of citizenship are. To eliminate poverty, to eliminate human suffering, to take care of people. We say the obligation of citizenship is shopping. We have a crisis, the president appears on television, and he says, “Go shop. Go to Disneyland.” The language has been emptied of any moral or political substance. We should be ashamed, in some way, of this flight from social responsibility. Its consequences are deadly. We see one of those consequences right now in the emergence of a political party and a leader with the fascist echoes of Nazi Germany.

CM: So is a vote for Trump, then, not just a loss of faith in Republicans or in Democrats, but in democracy in general? Is it a vote against collective responsibility?

HG: It is not simply a vote for a rightwing politician. It is a vote against democracy. The real struggle here that nobody wants to talk about is that the social and political divide in the United States is no longer just between the left and the right. It’s between those who believe in democracy and those who don’t.

Let’s be clear about this. What we are on the verge of facing is not simply the emergence of another rightwing lunatic who’s going to throw the United States and the world into chaos. We’re talking about Argentina in ’73. We’re talking about the rise of a Pinochet. We’re talking about the drastic elimination of what we might call democracy itself. Adam Gopnik, in his piece in the New Yorker, said that democracies don’t just commit suicide. They’re killed by murderers. And as flamboyant as that language might sound, in some cases, the urgency of the crisis that we face in the United States in this upcoming election is unlike anything we have ever seen. Because we’re not just talking about reform. We’re talking about the death of democracy.

CM: You write that “Hillary Clinton is the underside of the new neoliberal oligarchy which indulges some progressive issues but is indebted ideologically and politically to a criminogenic culture of finance, racism, and war. Put differently, she represents a less obscene, less in-your-face form of authoritarianism, hardly a viable alternative to Trump.”

Can we vote against authoritarianism taking office in November?

HG: Yeah, we can. We can, because it seems to me that as bad as Clinton is, there’s no comparison to Trump. Trump doesn’t believe in climate change. Trump has his finger on the possibility of a nuclear holocaust. As bad as Clinton is, at least there’s a space where Clinton that can be worked with. There’s a language that can be held up against the underside of its violation. There’s a chance to mobilize against Clinton in ways that could build a social movement.

My friend Noam Chomsky has argued against a lot of people around this issue, and I’m with him on this. It’s clinically insane, at this point, to claim that Clinton is worse than Trump. I just don’t understand that. With Trump, we could see the end of the world. We could see the end of the species. We could see a nuclear holocaust. As bad as she is, she’s not Trump. Look at who Trump is surrounding himself with, look at the potential for violence, look at the racism: that’s not at all part of her language. This is not to say that she hasn’t done horrendous things. But I would rather have her in office so that we can at last begin once again to work on figuring out what we have to do to eliminate this two-party system and make sure that Trumpism is never on the register of political opposition, and what we can do to get rid of the Hillary Clintons of the world and the system that produced her.

With her, there’s at least room for radical struggles. Under Trump, there’s the potential of concentration camps and mass repression and violence. That strikes me as worse.

CM: One last question for you, Henry. There is fear that a Hillary Clinton presidency will be so bad that it won’t reflect any of the victories that progressives who were supporting Bernie Sanders may have made, and that the backlash if she has any failures will mean the country will move farther to the right; meanwhile Clinton, in order to cater to that right, will push through legislation that a Republican could never pass (like privatizing social security), and anything that she does that’s seen as a failure will be blamed on progressivism.

Is Trump still worse than a Hillary presidency that privatizes social security and turns its back on all the Sanders stances that attracted so many?

HG: Absolutely. It’s between concentration camps, the total suppression of dissent, the use of state violence, the massive suppression of all the kinds of institutions that matter on the one hand, and on the other a Hillary Clinton that will teach us once again that there’s no chance for reform within the Democratic Party. Rather than bewailing what Hillary will inevitably do, let’s get real. Let’s build the institutions, let’s build the movements. Let’s stop fragmenting the left. Let’s get together and see this as an enormous opportunity to redefine the meaning of politics. Let’s get radical. Let’s talk about radical democracy. Let’s talk about justice. And let’s make Hillary Clinton a perfect example of what we don’t want.

CM: Henry, I love having you on This is Hell! Thank you so much for all your years of support.

HG: Chuck, thanks so much for inviting me.

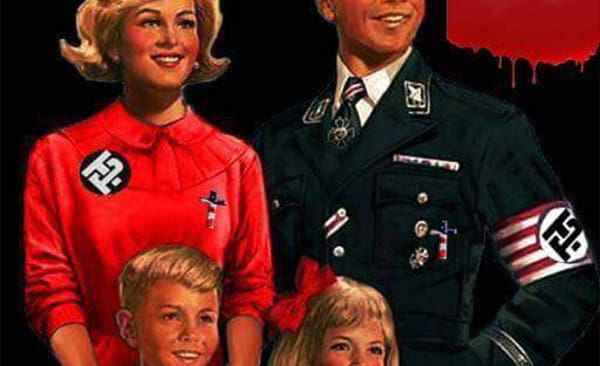

Featured image source: Twitter