Notes from Calais

by Ben Reynolds for Fragments

29 October 2016 (original post)

On Monday, 24 October, the French government started implementing its plan to evict the migrant camp known as “the Jungle” on the outskirts of Calais. Prior to the eviction, the camp hosted around ten thousand migrants from countries like Syria, Sudan, Afghanistan, Kurdistan, and Eritrea. Almost all of the migrants in the Jungle wanted to reach the United Kingdom, where they would then be eligible to apply for asylum. The Jungle drew these migrants because of its proximity to trucking routes through the Channel Tunnel. The camp had long been the site of serious contestation between, on one side, migrants who created their own forms of organization for survival and political action and European activists like the No Borders groups, and on the other, the French police and local government. The French government decided to resolve this problem by offering migrants a choice: either register for asylum in France and get bused to temporary accommodation, giving up the right to go to the UK, or rough it in the French countryside, keep trying to make it to the UK, and risk deportation if we find you and arrest you. Whatever you choose, the Jungle is being demolished and you will leave Calais.

A friend and I traveled to Calais that Monday to do what we could to help those now under threat of eviction. We stayed with comrades who have been working in the camp for many months. I am not an expert or authority on migration, the Jungle, or the experiences of the migrants who lived there. I simply want to present some of the things I saw, as I saw them, in hopes of contradicting the extraordinarily misleading media narratives circulating around the eviction of the Jungle. Unless otherwise noted, migrant quotations are translated from the original Arabic. I leave these scattered recollections below.

* * *

It’s Tuesday, late morning. We drive to meet a friend of our comrades, a lawyer, who is stuck outside one of the main entrances to the camp. As the eviction plans got underway, the French police posted warning signs around the camp’s borders stating that anyone without an official pass would be subject to arrest and fines of over a thousand euros. The local prefecture generously offered seven hundred such passes to journalists from all over the world but only five hundred to aid workers, meaning that many of those who had been working in the camp for months and even well over a year (including our comrades) had no passes. We hear that two No Borders activists – radicals who have been living in the camp and doing solidarity work since the camp first arose – have been arrested, and it seems that the cops are enforcing the rules at the camp entrances. The comrades we’re staying with still have vital work to do in the camp – they need to check on their migrant friends, deliver supplies, and get some out of the camp by nightfall. We confer for awhile, hearing reports of others who have been able to sneak into the camp through unsecured routes. We drive into town, hoping to get some press passes off of journalists who might already be leaving. No luck. One offers to hide us in the back of his van, but we suspect this is overly optimistic.

We return to the outskirts of the camp, deciding to try our luck crossing through the fields on the camp’s southern border. The outskirts are ringed by CRS vans carrying France’s notoriously brutal riot police. Cops are milling around everywhere. The municipality has brought in as many as seven thousand from all over France for the eviction. We walk through the tall, yellow grass past a small ramshackle school complex, one of the only remnants of the eviction of the camp’s southern half earlier this year, which pushed all of the camp’s residents into half the space they previously occupied. Scattered plumes of smoke rise from the camp in the distance. We reach a dirt road guarded by a CRS van and a squad of cops. We keep our heads down, hoping to wander through unannounced, but they stop us. Maybe we look a little bit too “No Borders.” My friend, who speaks fluent French, starts explaining that we work with an organization in the camp doing translation and legal work. We all do our best to look meek and confused. For some reason, they change their minds and wave us through. French chauvinism, for once, works in our favor.

We walk down the road, passing a church erected by the Eritrean migrants. The gate is painted in beautiful sky blue with deep red lettering and crosses. When we pass by the church again on Wednesday, we’ll hear hauntingly beautiful singing echoing from inside. It will remain, mercifully, far enough removed from the rest of the camp that it will be untouched by the fires. We pass by volunteers distributing hot food from the back of a van. Finally, we reach the camp. The ground is a soft mud that seems like it never dries, cut with footprints and tire tracks and small puddles that soak into your shoes. The structures on the main road are cobbled together from scrap wood and the odd bit of sheet metal. Some were restaurants, kitchens, and stores, and they still bear the bright paint and slogans that advertised their wares, but most are broken up and closed down due to the coming eviction. Behind the wooden structures are seemingly endless rows of battered, dusty tents, connected by a labyrinth of tiny foot paths. In rare form for Calais, which is cold and damp and rainy as a matter of course, the sun is shining and it’s warm.

We link up with some English volunteers offering to take Polaroid photos for the migrants. They explain that journalists come into the camp and take incessant photos of its people without ever asking. They never give these photos to their subjects. Instead, they offer them up for public consumption, casting the migrants as either pitiful victims or Islamist rapists coming to destroy little England. For what it’s worth, the migrants do seem to love the Polaroid photos. Some kids flash beaming smiles as they have their photo taken. For once, they will be the ones with control over their own image. No one else will have a copy.

The English volunteers tell us that they know someone who has a problem, but that he only speaks Arabic and needs a translator. He’s a shy, soft-spoken Sudanese man with a weathered face but the thin body of a teenager. It takes us some time to adjust to his accent – my dialect is Levantine and my friend’s is Mauritanian – but he explains to us that he wants to apply for asylum in the UK as an unaccompanied minor. Of the migrants in the camp, all of whom want to make it to the UK, only minors without families are eligible to apply for asylum there. The authorities tell the migrants that these minors will be the first to be bused out of the camp and across the Channel before the eviction starts. It later turns out that the children, in fact, will be the last to leave. After registering, they’re to be housed in shipping containers until everyone else has been cleared from the camp. Even when the fires start ripping through the camp on Tuesday night, the children are made to stay in the containers. After leaving, we hear that children who have been unable to register (because the registration areas close without warning) are being rounded up and arrested without explanation.

We take our new friend to an aid worker with the organization in charge of registering unaccompanied minors. We explain his situation, but the aid worker tells us in no uncertain terms that he has no chance of being registered as a minor. We learn that the “process” for determining the age of the migrants is a single French woman who decides, without any additional evidence, whether the applicants appear to be under eighteen. If you’re too tall, can grow a beard, or too weathered, you’re not a minor. If you’re short, have youthful features, and no beard, you might be in. We now have to explain to our friend that his application will not be accepted, and that his remaining options are to apply for asylum in France or try to make it to the UK illegally and face deportation. He receives this news without flinching, thanks us, and lets us know that he’ll have to think about it. After some minutes, we rejoin the volunteers and turn and walk into the camp.

* * *

Tuesday, late afternoon. A tense quiet settles over the camp. We’re leaving with our comrades and some Syrian friends. As we move to start cutting back through the southern field, two journalists swagger past, probably British. One woman, one man. Official press passes swinging from their necks. She’s properly made up and holding a microphone. He’s bald and wearing a bulletproof vest with steel plates. We can barely stifle our incredulity. One of our Syrian friends, a teenager, laughs: “What is this, Dara’a?”

* * *

It turns out that the demolition of the camp is pure spectacle, designed to satisfy an increasingly right-wing French public. Next year’s elections loom ominously for the ruling “Socialist” Party, with the far right National Front gaining ground across France. We hear that migrants are often the victims of fascist attacks in and around Calais, either being beaten by organized groups or ambushed from moving cars and motorcycles. On Tuesday night we hear that, despite security procedures to keep the destinations of registered migrants secret, a few busloads of migrants are turned away from a rural French town by armed fascist gangs. (I want to point out briefly that I am not using the term “fascist” pejoratively. The people in question are literally self-identifying fascists.) So the French government decides it’s going to “evict” the Jungle, and brings in seven hundred journalists from all over the world to bear witness to its well-organized, humane, right-on-schedule little eviction. Law and order for the fascists, humanity and ‘European values’ for the more liberal racists.

This eviction consists, as of Tuesday night, solely of a photo op. At maximum, a little over two thousand migrants of the ten thousand have been registered, despite the government’s pledge to evict the entirety of the camp by Thursday. Registration lines are completely overwhelmed and regularly close down in the early afternoon. There is no way that enough migrants will be registered by Friday, and word circulates that the eviction is actually going to take much longer than expected. Still, the local prefecture and the police invite the journalists down to witness their little sham eviction: a couple tiny bulldozers raze around twenty uninhabited tents on the far side of the camp. The venerable media – including the BBC – dutifully reports that the eviction is going ahead right on schedule. Everything is fine. The government has things under control.

* * *

“We used to say ‘The war will end, Syria will be fine.’ Now we say ‘Syria is over, the war will be fine.’”

– Syrian refugee

* * *

As Tuesday afternoon fades into evening, we sit with our comrades and Syrian friends in a cramped little caravan. The Syrians make dinner, we share tea and coffee, and we talk about the events of the day and the rumors we’ve heard. This is likely one of the darkest periods in the history of the Jungle. Everyone is tense, waiting to see what happens next. The reality is that no one has any idea what the future has in store – not the government, not the NGOs, and certainly not the migrants. According to our friends, a large number of the migrants who were living in the camp have probably already fled into the French countryside.

And yet, despite the endless succession of bad news, setbacks, and betrayals and fuck ups on the part of the French government, our friends are still laughing. They’re joking with us, telling stories, sharing what little they have in food and drink. They’re patiently trying to get nuanced Arabic phrases through our thick skulls. This, despite the fact that one of our friends has just learned that his family’s application for asylum in a certain country in the Western Hemisphere has been denied. Another is very, very sick and cannot get proper medical care in France. All have not seen their families or homeland in as many as five or six years. They have no idea where they’ll be going tomorrow when they get loaded onto a bus, potentially giving up any legal opportunity to make it to the UK. They’ve just heard that many of the other Syrians don’t want to go on the bus, that they’re saying they’ll protest and resist even though they know that the cops will brutalize and arrest them. And here they are, sitting with us, not crying but laughing.

This is why the politics of pity makes me sick. At best, what we get from the mass media is another insidious version of this whole fucking spectacle. It’s not “look at these rapists,” it’s “look at these poor, poor refugees. Can’t we at least take pity on them?” Make no mistake, the conditions in the Jungle are horrible. The experiences and conditions from which the migrants are fleeing are even worse. But the migrants who live in the squalor and brutality of places like the Jungle are not pitiful. Not in the least.

Migrants do not need our pity. We don’t deserve to pity them. They are stronger than us. They have been through trauma that would break the pitiable little bureaucrats who review asylum applications a thousand times over. How many of us could do what they have done? Imagine, for a second: You live in the United Kingdom. Your country descends into civil war. You watch friends and family die right in front of you. You have an uncle who lives in a safe country. This country is Afghanistan, a place you’ve never been to and know little about. Now, go to Afghanistan. You’ll travel most of the way on foot, being hounded by police and fascists the entire way, crossing borders and barbed wire and seas and rivers. Five years from now, you’ll be just across the border from Afghanistan. You’re so close, but still so far. You just have to make it across to claim asylum. Now, you hear that the border camp you’ve been sheltering in is going to be evicted. You have two options: flee to the countryside, or accept that you may never get to Afghanistan. Ever. And here you are, after all this, pouring tea and coffee for Afghan activists in a little caravan, laughing. Laughing.

These people are intelligent, sophisticated, charming, and funny. They bear their scars with dignity. I am not romanticizing the migrant condition. I am not trying to reduce the migrant experience to some essential characteristics, no matter how flattering those characteristics might be. These are facts that I saw with my own eyes. Yes, there are those among the migrants who are truly wounded. There are a few who have been subjected to so much violence that they might reflect that violence outward again. But on the whole, the migrants in the Jungle are some of the strongest people I have ever met in my entire life, and that is likely to remain the case as long as I live.

* * *

Late Tuesday night. Sometime between midnight and one a.m. We’re hearing reports of fires in the Jungle. Friends of our comrades and many migrants are still in the camp. Updates keep coming in and it seems like the fires aren’t being put out quickly enough. They’re spreading. We decide to head back to the camp. The Syrians donate their own bread and clean drinking water to be distributed to those fleeing the fires. We speed down the road, cutting through sleepy little French hamlets. Finally, we arrive outside the western entrance to the camp, an overpass known as “the Bridge.” Cops and their vans and their blue flashing lights are everywhere, along with a collection of mostly pass-less volunteers. We grab the water and head down to the outskirts of the camp.

As we pass under the bridge, we finally catch sight of the Jungle. Smoke is rising everywhere, and the fires are blazing so high that you can see them over the small hill that surrounds the camp’s western border. People are still coming out of the camp, many are just milling around looking at the fires. When a fire reaches a butane cooking stove, there’s a small explosion. Flames lick the sky. We meet up with some Sudanese friends of our comrades. They explain that many people are still in the camp, and some might even still be sleeping. Others have scattered all around the outskirts. We bring water to some of the Sudanese migrants sleeping in the mud under the bridge, we drop off the rest with other volunteers handing out sleeping bags and food and water from a van. Our comrades rush off to find the rest of their friends and bring sleeping bags back from a warehouse. The cops, for their part, do nothing. They patrol the outside of the camp, but are too afraid to go inside. Fire trucks arrive maybe an hour or two after the fires start, but the fires are still blazing when they leave.

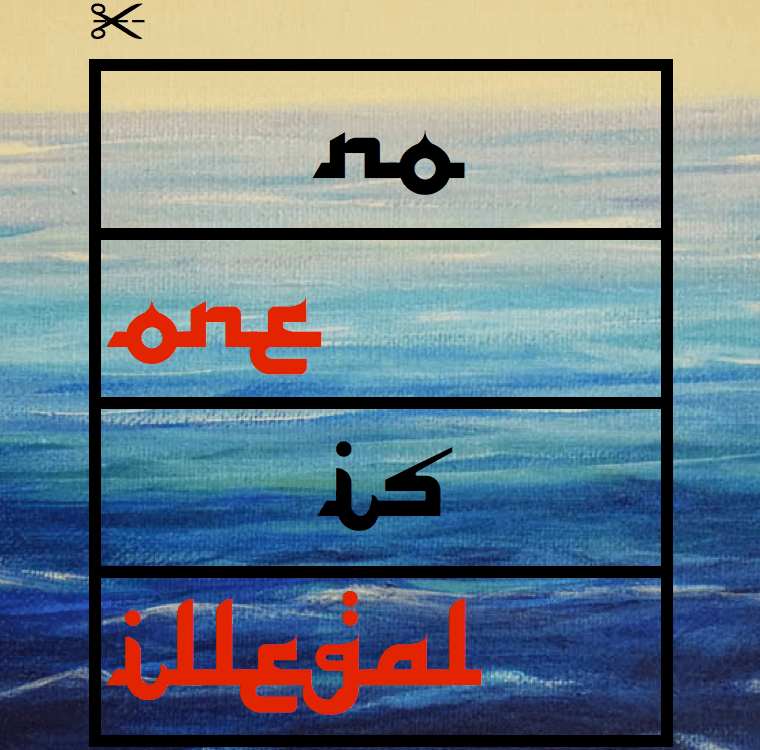

We spend the rest of the night with our Sudanese friends in the mud under the Bridge. The overpass walls are scrawled with a mixture of anarchist and migrant graffiti. NO BORDERS, NO NATIONS. LONDON CALLING. FREE SYRIA. We talk and joke, and they share their water and food with us no matter how desperately we try to resist. I’m wearing two jackets and a thick scarf, but it’s still absolutely freezing. Until some Christian volunteers arrive with extra blankets, the Sudanese children and teenagers are shivering and huddling together under their sleeping bags.

A charming young Sudanese man explains to us that he has no intention of registering with the French authorities. He says that many of the migrants, like himself, will scatter to smaller camps throughout northern France. He says that he has no problem roughing it in the countryside. He’s been through worse. We later estimate that as much as half of the population of the camp won’t end up registering. Though many of the migrants throughout the day have been saying that this is the end, the Jungle is over, he disagrees. “There will always be another Jungle,” he explains. As long as people want to get to the UK, they’ll find a way to live near the smuggling routes. What are now small camps will turn into big camps as migrants make it to France. Who knows, maybe even the camp at Calais will be rebuilt. What could moving 10,000 refugees possibly accomplish? It’s a drop in the bucket. Germany will receive over a million asylum claims this year. We know this. The migrants know this. The French know this. And here we are, sitting in the mud, watching the Jungle burn to the ground so that the folks at home can all feel good about the nice, humane European governments who have everything under control.

* * *

After a couple hours of sleep on the caravan floor, we head back to the camp on Wednesday morning. Our Syrian friends are going to register and get bused off to an accommodation center today, and there are still more migrants in the camp who need last minute aid. We park outside the southern field and head into the camp. The fires are still raging and the sky is choked with thick black smoke.

One of our comrades needs to link up with friends in the camp. We head past the Bridge toward the registration lines, where confusion reigns. The cops have cut off the road, preventing everyone assembled from getting to the registration area. We head back toward the camp, but the cops have formed another line blocking the Bridge entrance and they won’t let anyone back through. There’s a big fire raging close to the camp’s western border, which they now apparently care about (despite the lack of any effort to put the fire out). Entrance denied. We watch firsthand as uniformed medics are turned away from entering the camp. This is against the law. We later hear from a photographer who was stuck inside the camp near the fires that there were multiple injuries, including serious burns. He cheerfully adds, however, that “no one died.”

Despite the harassment from the police, the mood has noticeably changed. Tension and defiance have been replaced by sheer exhaustion. No one seems to have slept much. Despite this, the cops bring in multiple additional riot squads in full gear. They threaten to fire tear gas at the people trying to get past their cordon. The simple presence of tired, listless migrant teenagers seems to be enough to seriously unnerve the bespectacled CRS commander, who paces nervously.

We head back toward the registration lines to help out where we can. We do our best to assist a kind, older Sudanese man with serious diabetic foot problems. Finally, our Syrian friends show up. It seems that the fires changed the community’s mind about the possibilities for protest and resistance. They line up to board the buses together. A French NGO official makes a comment that I can’t make out and one of our friends sharply replies that “the Syrians are not the problem here.” We say our goodbyes and wish each other well. One of our Syrian friends takes my water bottle from me and fills it up with his own water before he goes. He refuses to stop until it’s full. The NGO officials call out and it’s finally time to board the buses. The line of riot cops opens up enough to let the Syrians through, single file.

It’s afternoon. My friend and I have to leave if we’re going to make our ferry to Dover. The fires are still burning and the cops still aren’t letting people past the Bridge. We head up a side street and luckily catch a cab to the port.

* * *

I’m at the ferry terminal in Calais, and I hand my passport over to the border police. No problem. We board the ferry. It has a bar that offers coffee. Starbucks cappuccinos. Cold drinks, if you want. Pre-made sandwiches. I’m ferried from one side of the Channel to the other. I’m not harassed by the police. I’m not beaten by batons or smashed with riot shields. I’m not chased by dogs. I’m not tear gassed. I’m not attacked by fascists. I’m not imprisoned. I’m not deported back to my home country where I’ll face war or torture or death. Tonight, instead of the mud under the Bridge or a tent or a cold caravan floor, I’ll sleep in a bed in a room with heat.

Yet, I’m still back in that camp. I’m still wondering what will happen to those who are still stuck in the Jungle. I’m still praying that the friends we met will find some way to get asylum. I’m hoping that they’ll make it to the UK, that they’ll get proper medical care, and that they’ll see their families again. I feel powerless. I’m not making asylum decisions, I’m not making immigration policy. I can do what I can, as one person, but it will never be enough. I’m still stuck in a West that is steadily walking, yet again, toward a politics of ethnic hatred and fascist terror. A single droplet can’t change the tide.

So, here I sit, looking for other droplets. I hope that these memories find others who are willing to do whatever it takes to bring this barbarism to an end. Because, until the day when borders themselves are a mere memory, there will always be another Jungle.

Featured image source: Calais Action (Facebook)