AntiNote: This text is a modified version of a talk which Syrian dissident Yassin al-Haj Saleh delivered at the first meeting of the Lancet Commission on Syria, held at the American University of Beirut, Lebanon, 1-2 December 2016. It appeared in raw form on multiple Syria-oriented blogs on 21 January 2017. We have modified it further (editing it lightly for readability).

Syria is the World, the World is Syria

by Yassin al-Haj Saleh

(original post)

The world contributed to aggravating the Syrian malady, which in turn has made the world sicker. The world that left Syria to shatter has in so doing become more Syrian itself, and is walking on the path of self-destruction. What we need to do is change the world that prevented change in Syria.

In March of the coming year, when six years will have passed since the Syrian Revolution started, its crushing will have perhaps been completed, shattering the lives of countless people and obliterating what remains of the society they live in. As we know, after a revolution is crushed there comes the brutal counter-revolution, in which the crushing of the revolution and its communities continues—in this case carried out by a confounding and precarious configuration of foreign authorities (Russian and Iranian) and the domestic fascist enforcer.

This is not a subjective anticipation of atrocities that may or may not happen in the future; it is based on what we have already witnessed in Syria in recent years (as well as decades ago, when the Assadi state crushed another social rebellion, in the early 1980s), and on the reliable historical pattern indicating that dominant elites retaliate brutally against those who dared revolt after they defeat them.

Syrians have fallen under prolonged and profoundly cruel tyranny: the Assadi regime has gone to war against its subjects twice, the first time in the late seventies and early eighties, and again over the past nearly six years. The violence of the Assadi state against its subjects is not punitive, exactly; it should rather be understood as based on humiliation. In the first war, this violence caused the deaths of tens of thousands; tens of thousands more were arrested and tortured, their lives destroyed. In the second war, hundreds of thousands have been killed—with similar numbers detained or tortured—while refugees and the displaced number in the millions. All of this happened right before the eyes of the so-called international community, over months and years.

How can this be explained? I think it has something to do with Syria being a microcosm of the world (in a region that is the most internationalized in the world, the Middle East), and the world being in essence a macro-Syria. In Syria, the world recognizes itself—the self that it does not want to change or reconsider, does not have the will to face and repair. The world, through its international institutions and major players, is in a constant state of denial about its responsibility for the extremist composition of the contemporary Middle East, which was and is based on minoritarian rule, extremism and exception (Israel and Saudi Arabia being the most prominent examples). The Assadi regime in Syria is also based on this trinity—minoritarian rule, extremism, and exception—and does not allow the people to have a say in the political structures that govern them. This has paved the way for the ongoing massacre against them for the past six years.

In 2013, after the regime committed a chemical massacre in Ghouta, the Americans and the Russians came to a sordid deal that ensured the survival of a regime that had violated international law and crossed Mr. Obama’s “red line,” murdering 1,466 of its subjects in the space of an hour. The offender was stripped of one type of weapon (the possession of which is considered the right of the international elite only), but was effectively given license to continue killing by other means. And that is just what the Assadi state did—with everyone’s knowledge and under their watch. The shabiha regime continuously invited additional partners to participate in the murder feast, which proceeds to this day.

The international parties that signed the deal lacked neither the information nor the awareness of what was happening in the country. Everything was clear and known to all. It seems, according to the information available, that the inspiration for the criminal deal came from Syria’s Israeli neighbor, which itself has always enjoyed extreme exception from the rules of international justice—it is another elitist state that has been given full license to continue its own killing.

What we have witnessed for years in Syria—and before that in Iraq, Lebanon, and Palestine—is the extremest form of exposure for defenseless people, the condition of philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s homo sacer (someone whose killing has no meaning or sacrificial value). Not only have Syrians been killed in abundance; they are killed and blamed, killed and slandered, killed and dehumanized, exterminated like pests. They are supposed to have deserved being killed, due to their fanaticism or terrorism. Their deaths are not considered acts of sacrifice that have any emancipatory meaning.

No one in the whole world, except a few people here and there, acknowledge that this is a genocide of the Holocaust type. Why not? Simply put: because no one is willing to see the Nazi when he looks in the mirror. But western cultural and geopolitical discourses have viewed the Middle East as essentially empty of humans for a generation already, if not longer—and dehumanization becomes depopulation soon enough. These discourses are thus genocidal discourses.

This extreme injustice is contagious, both regionally and globally.

It affected Syria before any other. The rabies of extremism spread in Syria strongly after the criminal chemical deal, which was a heavenly gift to nihilistic Islamic organizations. However, there is a global state of denial about these formations: they are considered a special product of our particular societies, of our history and religion. But really these types of formations can arise anywhere, they arise out of the modern world, wherever extreme oligarchic regimes provide them fertile soil to live and grow. Nonetheless, these nihilistic formations have certainly poisoned the lives of many Syrians, many Iraqis, many Middle Easterners. In this way, they are in fact complementary to the impact of the forces of international control and local extremist regimes.

The plague of extremism and discrimination spreads throughout the region, of course, in Iran and Iraq, in the Gulf, in Egypt and Libya. Extreme ideology brings hatred and hate crimes. Formations like Daesh and al Qaeda, as well as Shiite militias such as the Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces, are forces of active hatred.

The world at large constitutes the environment for this contagion. The forces that invest in fear—forces for whom a fearful atmosphere is the preferred, natural political environment—regard the stranger, the immigrant, and the refugee as a danger, a source of pollution. “Never again,” it seems, does not apply to the Syrians. They are utterly exposed, and their extermination is not a big problem.

The world that left Syria to shatter has in so doing become more Syrian itself, and is walking on the path of self-destruction. The world’s reserves of hope, altruism and confidence appear to be at their lowest levels since at least World War II, and despair, selfishness, fear of the future and distrust of the neighbor are progressing in the world.

In our view as Syrians: the world is a Syrian issue. It sounds like I said something the wrong way around there, but I did not. The world is a Syrian issue. The main issue is no longer Syria, it is the world. What we need to do is change the world that prevented change in Syria. This is simple logic. And since it does not appear that there are opportunities for liberatory change in the world today, it is likely that we are going to face more globally-spread fear, despair and hatred, more violence and humiliation, more hardened souls and insensitivity. Trump has been elected in America, and maybe soon Fillon in France—the rise of the populist right in Europe and the triumphal ascendancy of Putin and Bashar Assad, Netanyahu and Abdul Fattah el-Sisi: these are all dreadful signs of a progressively shattered world.

The world is a Syrian issue, definitely. But before that, of course, it bears repeating that Syria is a global issue. Four permanent members of the UN Security Council are in a state of war in Syria, and the fifth, China, offers training and support to the murderer, in addition to political cover. Israel has bombed in Syria whenever it sees fit. Iran and its followers in Iraq and Lebanon are participating in the murder feast. Turkey today is on Syrian territory. Nihilist Sunni jihadists from dozens of countries are fighting in Syria, and there are Kurdish fighters from four or five countries…

Despite all this, there are no serious indications that Syria is indeed regarded as a global issue that needs to be resolved on the basis of justice and equity, or at least something close. The contemporary world contributed to aggravating the Syrian malady, which in turn has made the world sicker. The problem today is not that the world is not helping us; the problem is that the world is not helping itself. The world, our one world, is left abandoned, with no one to care about it, and no one to represent it while the major powers act according to a selfish and narrow-minded logic (leading to a deteriorating situation in these countries themselves as well, not only in the world as a whole). International institutions are empty and helpless, and their global stature is weaker than any other time since the emergence of the United Nations nearly seventy years ago.

This global resignation does not bode well for anyone.

As Syrians we have found ourselves thinking more globally—not only because we are bitter and angry at the world for leaving us to be killed for more than 2,000 days; not because we think we know the world better than others; not because almost the whole world is literally in Syria; but primarily because we have become in the world. We have been thrown outside our country; our trajectories are those of dispersion all over the world, vulnerable and without legal or institutional protections, without recognized status; we are not concentrated in any one country; we are everywhere, and still moving. One could be in one place now, but he does not know where he will be tomorrow. We are here and there, and we are neither here nor there (to quote the great Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish). We, along with the Syrian Palestinians, have become more global than any people in the world today.

This does not mean that we are uniquely able to tell the truth to or about the world, nor that we are closer to the essence of the world than others, but it does mean that the world is for us, more than for anyone else in the world; it is our project. The world is a trajectory, not a reality, and we have been thrown in divergent and convergent trajectories around this trajectorial world. We are the world.

You want to know something about the world? Have a closer look at Syria and at the trajectories of Syrians or Palestinian Syrians, and their destinies.

Yassin al-Haj Saleh is a Syrian writer, based in Istanbul since late 2013. He was imprisoned from 1980 to 1996 for being a member of a communist party opposing the Hafez al-Assad regime. He is the author of several books on Syria, prison, Islam, and culture.

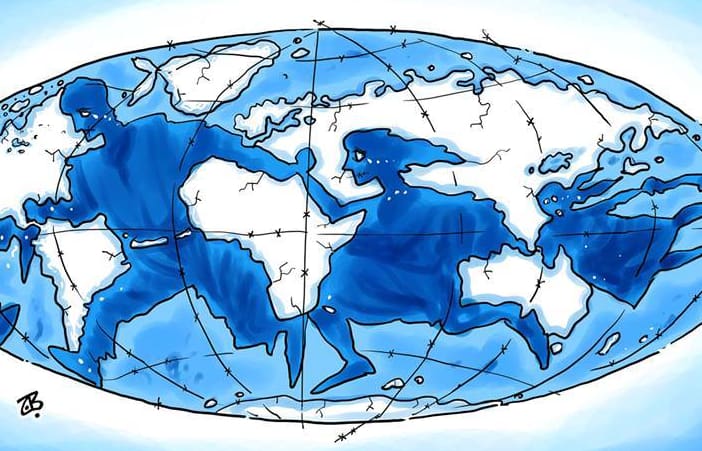

Featured Image: World Refugee Day by Imad Hajjaj

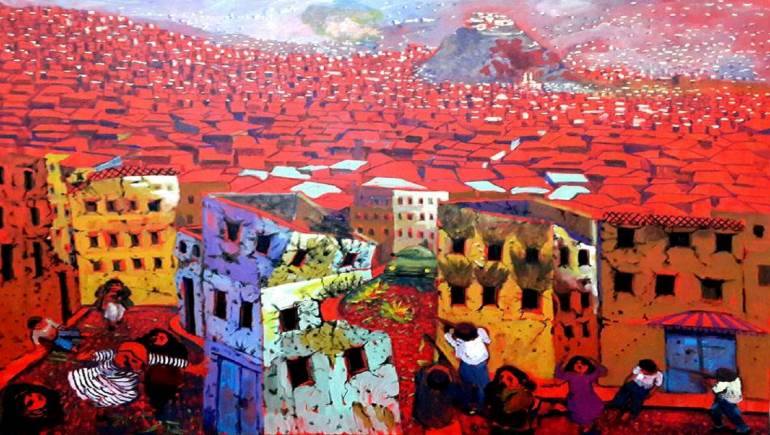

Source of all images: Dawlaty.org (Facebook)