AntiNote: Conditions continue to deteriorate, detentions extend, and deportations accelerate on the Greek frontier islands. The widely reviled EU-Turkey pact of March 2016 has “finally” been kicking into gear, and it is both worse than we feared and getting less attention than we dared hope. The following is two months’ worth of testimony from Lesvos on developments and repressions there. Please support these activists who are supplying some of the only authentic aid and solidarity available to travelers stuck in Lesvos as well as some of the only authentic street-level information available to those few elsewhere still interested in this epochal struggle.

Deportations, Deportations, and More Deportations

by No Borders Kitchen Lesvos

20 April 2017 (original post)

In the last weeks the repression on Lesvos has continued. There have been more forced deportations to Turkey, and the asylum procedure is still a tangle of bureaucratic nightmares, especially for people of certain nationalities. This situation creates a great hopelessness. Many people’s mental health is getting worse and a lot of people sign for a so called “voluntary return” to their home countries as their only option to get off this island and not spend months in prison in Turkey.

Trying to get asylum on Lesvos often means further abuse and imprisonment for people already fleeing abuse and imprisonment in their home countries. Here are two stories emblematic of the deportation situation for those arriving in Greece.

A. arrived on Lesvos in April 2016. He had been waiting for almost a year in the hot-spot Moria to have his case examined. When they finally did so, his asylum claim was rejected. They picked him up on the street and brought him to prison in Moria. There he was held for two months and then transferred to the police station, where he was held for another month. Then he was deported to Turkey. He will spend six months in prison there. When his deportation to his home country finally happens he expects to be arrested at the airport upon arrival and again taken to prison.

B. also arrived in April 2016 after being released from a detention center in Turkey where they had held him for several months. After a year of waiting on Lesvos he was arrested in the camp when he tried to renew his papers. He was brought to the prison in Moria. There they forced him to apply for asylum. After a few days he had his interview. Because independent lawyers have no access to the camp he had no preparation for the interview and his case was rejected. He was tired of Lesvos and wants to get out of prison so he signed up for voluntary deportation. The process takes from weeks to many months in Lesvos. Ultimately he will be transferred to Athens into a detention center and imprisoned again for months. When he arrives at the airport of his home country he’ll have to bribe the police not to be taken to prison.

Deportations to Turkey

In April, a total of seventy people (for whom we have confirmed information) were deported from Lesvos to Turkey. 49 people were brought from Mytilini to Dikili on April 6, and another 21 persons on April 12. Most of them have citizenship in Algeria, Pakistan, Morocco or Bangladesh. Upon their arrival they are held in closed removal centers, essentially a prison. According to the people being held there, they are told they will be there for six months. We found that there is no maximum period of the detention—anything from a few weeks to several months to a year is possible. The people in the center are asked to pay for their deportation themselves, with the promise of being deported faster if they do so.

It is incredibly difficult to keep in contact with people deported to Turkey. Not even lawyers have good access to people in the removal centers. The detainees’ phones are confiscated with no access to friends, family or a lawyer. Their only option is to use the expensive payphones inside the prisons. If they are out of money they might lose contact to the outer world. Furthermore we have been told repeatedly about the horrible living conditions: no proper food, overcrowded cells, no cigarettes and lots of police abuse.

So-called “Voluntary Return”

To avoid being deported to Turkey, many people on Lesvos are signing for their own deportation with IOM (International Organization for Migration.) The IOM returns people to their country of origin. We have not been able to find official numbers of returns with IOM for the last two months (yet). As we have posted earlier, the so-called “voluntary return” is not as voluntary as IOM claims.

Voluntary returns are forced by the circumstances on this island. The hopelessness, the living conditions, the waiting, the fear of being returned to Turkey, the fear of spending months in prison, and always the fear of the police.

Voluntary deportees are now being promised 1000€.i

IOM’s website says that “voluntary return” is for people who do not apply for asylum or have been rejected, but it has not been possible for people who appeal a negative asylum decision, and were again rejected, to return under this IOM program. Instead they are forcefully returned to Turkey. We know of two cases who were returned to Turkey against their will after they signed for a voluntary return with IOM, but we believe there are many more.

“The International Organization for Migration (IOM) confirmed to News That Moves that people hosted on the Greek islands of Lesvos, Chios, Samos, Leros and Kos, who entered Greece after 20 March 2016 and whose asylum request has been rejected, have five days to either appeal against the rejection decision or ask for assistance from IOM for voluntary return to their home country, if eligible.”ii

This creates a situation were people have to decide between using their right to appeal the decision and maybe be deported to Turkey to spend months in prison there, or to return before having the chance of having their case examined by a court. Their right to a fair asylum procedure is undermined by the threats of imprisonment and forced deportation.

Arbitrary Detention and Biased Asylum Procedures

After signing for IOM deportation, some people are released from prison. Others sign and remain in jail for several months in Mytilini before being transferred to a jail in Athens and eventually deported. People never know how long they have to stay in prison. The two weeks some people are told by the police they have to stay sometimes turn into several months.

Prior to their deportation to Turkey, people are held for weeks and sometimes months in Mytilini either in the prison inside Moria or the police station in the city. While in the Moria prison they can keep their phones, they cannot do so in the police station. Here, just as in the Turkish centers, their only way to have outside contact is to use the pay phone. Visits are only possible for close family members—of which many have none on Lesvos.

As reported by [German humanitarian organization] Pro Asyl, arbitrary detention of asylum seekers is common on the islands, and new closed detention centers are already being established on the other islands. New laws are being established that basically make it possible to detain any asylum seeker on the islands.

“The legal framework defining the grounds for detention of refugees and migrants leaves many options for arbitrary detention, i.e. under the general grounds that persons who are accused of “law-breaking conduct” or are “considered to apply merely in order to delay or frustrate return” can be detained. These prerequisites open up the possibility to arbitrarily detain almost every protection seeker on the islands.”iii

In December, the EU states made a Joint Action plan for the implementation of the EU-Turkey Agreement. Among others things it stated that detention capacities on the islands should be increased. On Lesvos, people are detained based on their nationality; in particular, people from Pakistan, Bangladesh, Morocco, and Algeria are held during their asylum procedure. Therefore, the people of these nationalities have very little access to a fair asylum process. In prison it is hard for them to access independent legal aid prior to their interviews. Furthermore, the asylum process is negatively biased towards the people with the citizenships above. Many of the people who are in prison during their procedure are or will be deported back either to Turkey or to their home countries.

Even for people who have a chance of getting asylum, the situation is not good. The waiting times for interviews are very long. Some people have waited for many months just for their first interview. Often when their interview date comes and they go to Moria, they are told to come back again in a few days or weeks. Some people have had their interview date delayed five or six times before they could finally do it. There are also other faults in the system, like a lack of skilled translators and interviewers who are sensitive about gender-based violence as a reason for women fleeing their home countries. Furthermore, the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) [wow, just look at these ridiculous assholes’ website. —ed.] is losing interview records and therefore forcing people to go through the process a second time.

People who are granted asylum in Greece are left with nothing. They receive papers that allow them to stay in Greece but get no support whatsoever in order to survive and build a life for themselves here. Of course the responsibility for this does not lay only with Greece but rather with the EU politics of forcing people to apply in the first country they enter Europe and therefore forcing people to stay in the poorer southern European countries.

A conclusion about all of this? Everything on this island is totally fucked up and we don’t see where all of this is leading except to even more repression and more suffering.

Eviction of “Old Squat” for refugees on Lesvos

by No Borders Kitchen Lesvos (Facebook)

29 April 2017 (original post)

Yesterday one of the squats we supported was taken away by the cops and the Alpha Bank and turned from a home into an old abandoned unused building again. All people were arrested and detained for a day and might face charges for trespassing and destruction of property. Now many people are out on the street, with no safe place to go.

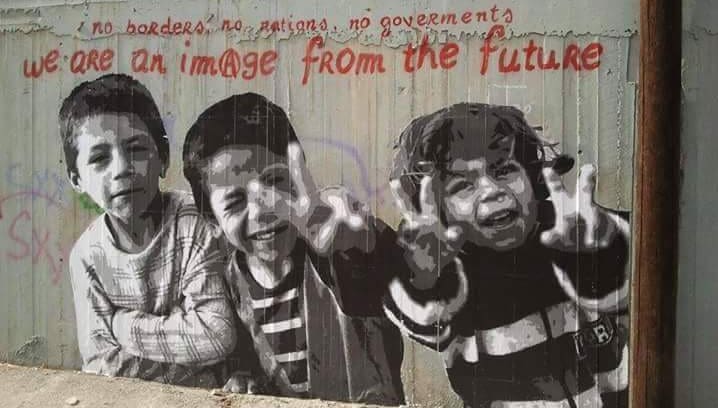

What happened yesterday leaves us sad and incredibly angry. What was destroyed by the state and capitalism was not just a building. It was a home. It was a community. It was a place for friendship, for solidarity, for struggling together against borders and the system that creates them.

The squat was not a perfect place. There was always rubbish lying around, the sound of the power factory next door was the lullaby and the toilet was rarely cleaned. But still we loved it.

Yesterday we were awakened at seven a.m. as the police kicked our doors over and over. When we came out of the rooms there were numerous policemen, regular city police and OPKE [special heavily armed police unit for “Crime Prevention and Suppression” —ed.], in the yard. Over the three days prior, we had already watched workers turning this home into a jail, so the eviction didn’t come as a complete surprise. Each day workers would continue placing the razor wire around the wall of the squat we supported and lived in, while we tried to decide if there was any way to resist.

At the time of the eviction there were around 35 people in the squat, and all were gathered in the yard. The segregation and racism began immediately as people that looked like “refugees” had to gather in one corner of the yard and everyone’s papers were checked and taken by the cops. Then people they considered “Europeans” or people with passports were also asked to give their passports. Some refugees were handcuffed to each other for no apparent reason. We tried to resist the separation but those who insisted on staying were pushed and dragged away. All people with Western passports were taken into an arrest van and brought to the police station. We were made to sit down in a corridor and were given contradictory information whether we were under arrest or taken for ID control only. While we were waiting, we saw that the refugees were also taken to the police station. They were all put into cells while everyone with a Western passport was kept in the hallway.

After hours of waiting, we were informed that we were all being accused of vandalism and trespassing. Every one of us was taken into an office and asked to sign papers written in Greek. Only oral translation into English was provided and we had to ask repeatedly for a complete oral translation of the documents. Everyone had their fingerprints and pictures taken. At around seven in the evening the last person was released from the police station. When the police let us go, they didn’t inform us if we had been formally charged or not. It is still unclear what will happen now, whether we will all face court or not. We left the police station with relief and happiness to feel the sun warming our skin and to see the faces of all the friends that were welcoming us outside. The relief lasted only a short while. The eviction left dozens of people without shelter, without any safe place to go. What was a home is now an empty building surrounded by NATO wire and guarded by security officers.

This eviction didn’t come as a surprise. In the last four months the repression of refugees—especially people without valid papers and of certain nationalities—as well as of solidarity movements has become worse each week. The destruction of any autonomous spaces for people to live was expected. Many friends we support living outside of the camps have been checked and arrested in the last months. There have been many steps taken in order to clear the streets and the city of refugees and keep as many people as possible within the confines of Moria camp. They have been tightening security at Moria, police presence on streets has become stronger, many people have been and are being detained during their asylum procedure, and deportations happen on a regular basis.

This time it was Alpha Bank, the owner of the building, that had the power to cause the most damage to us. It was Alpha Bank who pressed charges against us and pushed this eviction. We are sure that the building will not be used. It is very old, in the ugliest spot in Mytilini next to a power electric factory billowing steam and chemicals, causing air and noise pollution. No one wants this building, except those with no other option besides the prison that is Moria.

All of this also coincides with the announcement that all NGO and international groups will leave Lesvos by July 31. As we are one of a handful of groups without government contracts working outside the camps, the EU and Greek government would very much like to see No Borders disappear from Lesvos.

Unfortunately this eviction is not the end of a series of repressions but rather the beginning. We expect evictions of the remaining squats in the next weeks and months. Furthermore we also expect the arrests, imprisonments, and deportations to keep going.

But we are not ready to give up. We will stay here, we will continue to support the people in their struggle for freedom of movement and dignity. We will keep fighting.

We send a lot of Love and Rage to all people standing with us and fighting against all borders here on Lesvos and everywhere!

No Borders Call for Support

by No Borders Kitchen Lesvos

2 June 2017 (original post)

The No Borders squat in Lesvos was evicted five weeks ago, and it feels like we’re losing more space every day. It’s been a month of harsh police crackdowns on squatting and rough sleeping, vicious and increasingly frequent deportations, and dwindling financial support. The EU is funneling the thousands of refugees here into the Moria detention center, deporting them to face persecution and death abroad, and washing its blood-stained hands of the whole affair.

No Borders Kitchen is still here, still fighting and still providing food, care and legal support to hundreds of refugees, but our work is more difficult than ever before. Here’s how the situation has deteriorated for the roughly four thousand refugees trapped on Lesvos, how No Borders is struggling to respond, and what you can do to help out.

The “Beautiful Prison”

As the time refugees are trapped here lengthens, the island grows smaller and smaller. There is little else to do each day besides trudge to Moria to hear that no progress has been made on your case, fight over cooking oil, and skip stones in the Aegean Sea. People are making increasingly desperate attempts to escape Lesvos—the ‘beautiful prison,’ as one refugee recently described it. Earlier this month, one young man attempted suicide in Moria’s Section B detention center, stabbing himself in the chest with a switchblade. He remains incarcerated.

It is easy to think of time as standing still, but actually it is sliding away: people have been waiting for nine, twelve, eighteen months as interview dates are bungled, translators cannot be found, and the broken assessment system grinds slowly on. These months are taken off young lives, eating into education and careers among much else, and cannot be bought back at any cost.

There are months and months of nothing, and suddenly there is no time at all. Once an asylum application fails, as over ninety percent eventually do, refugees have five days to lodge an appeal before deportation. Many are not told they have this right and so are deported when they still stand a chance of securing asylum. Some physically sick refugees, and others with the legal right to remain, have been pulled off the deportation ferry by lawyers; others are illegally kicked out ahead of time. Friends of ours awaiting deportation in Section B are shivering with sickness, while others are covered in historic torture wounds and recent self-harm scars. If they are not stopped, these deportations will kill.

Deportees are taken from Moria to the port under cover of darkness, but deported under the cover of tourist-trap sunlight. Handcuffed and stripped of their mobile phones, they are muscled onto private ferries, and the holiday-makers around the harbor never realize human rights are being infringed twenty yards from their cocktail bars. Official figures show 129 deportations under the EU-Turkey deal from Lesvos since the start of April. And as the EU is finally clearing its backlog of stranded refugees—by deporting the overwhelming majority—we expect a severe increase in arrests, detention, and associated police violence.

Some deportees attempt a return as soon as they escape detention abroad. “Until they die, they will never stop coming back,” one Pakistani refugee recently said. Many take the suicidal Libyan route, through waters where an EU-trained coast guard sprays bullets at drowning toddlers and deaths are so common they seldom make the news.

Giving up any hope of claiming asylum, those opting for so-called ‘voluntary return’ are bribed and coerced into returning to life-threatening danger in their home countries. Following a lengthy jail spell in Athens, they are imprisoned for months in Pakistan or Afghanistan, until a family member can bribe an official to have them released. For families who spent all they had to send one child to the imagined safety of Europe, this is often impossible, while violence, abuse, and suicide are of course rampant in these prisons as well.

No Space

Every time we walk the long, hot coastal road from the city center to Moria, we pass the mocking empty space of the old No Borders squat, still daubed with anti-patriarchy graffiti but now ringed with razor wire and under 24-hour security surveillance. Scores of refugees and activists ate, slept, and lived together here in shared struggle.

The squat’s eviction and closure makes it hard to even meet with our refugee friends, let alone support them in resisting deportation. For the crime of sheltering in a derelict building, refugees have been hit with heavy legal fees and court cases which will badly affect their asylum claims. Some former squatters now sleep on the beach or in the woods, and some have returned to Moria. Others have opted for voluntary return, preferring an unknown prison sentence to the certitude of sectarian violence in the prison camp.

The remaining squats are increasingly violent and volatile. Friends of ours have been beaten, robbed of their mobile phones, and extorted for the safe return of sim cards containing their only contacts to their families back home. These squats also face imminent eviction: a derelict white building we called ‘Casablanca’ was forcibly cleared out, and all its occupants detained or charged with squatting, just two days ago.

Pending court cases, combined with the police’s increasingly violent and zero-tolerance approach to squatting, mean we cannot find a new space to live together. While we continue to find shelter for the most vulnerable, we are forced to tell many refugees in desperate need of shelter that we can no longer keep them warm and safe overnight.

Our Work

Food is the focus of our practical support. Each week we provide up to three hundred refugees with all the ingredients they need to cook for themselves and subsist autonomously, packing up boxes in an abandoned strip club and distributing them in squats and parking lots around the island.

Every month we distribute over 1500kg (each) of flour and rice, 800kg of potatoes, and hundreds of kilograms of fresh fruit and vegetables, lentils and pasta, plus spices, tea, coffee, cooking oil and toiletries. We receive more requests for boxes daily, and are currently forced to turn families away due to a lack of funds. Each day, we provide a hot meal to around sixty refugees, catering to those unable to cook for themselves and creating a small ad hoc social space, and have recently started meeting for tea, coffee, and hot food with refugees living in Moria. We also feed desperately impoverished Roma families, marginalized and persecuted here since before a single refugee arrived.

Drawing on our network of contacts across the island, in Moria, and in detention, we are now offering material support and legal assistance to detained refugees. All deportations are cruel, violent and illegitimate, but many are also illegal, and we are working alongside lawyers and refugee activists to save people from forcible transfer to Turkey. All our work enables us to stand in close, personal solidarity with our refugee friends, particularly those shut out of the asylum system and failed by the big NGOs, and support them in their struggle for asylum and dignity in countless different ways every day.

Our Needs

Many more refugees will arrive in Lesvos over the coming summer months, as people-smugglers take advantage of the clear nights and heavy maritime traffic. Sixteen people recently drowned offshore, while four boats containing hundreds of refugees made land just this weekend. Since the EU-Turkey deal began on 18 March 2016, the number of migrants stranded in Greece has actually increased by 45%. Thousands of new arrivals are currently being dispatched by Turkish smugglers to nearby Chios, and many will be transferred here for detention and deportation.

As the tourism season comes around, Frontex will prevent the ugly sight of refugees washing up on golden beaches by intercepting them in dangerous deep water, and the police will come down even harder on paperless refugees sleeping rough among the olive groves and cobbled streets of Mytilini. The EU is trying to squeeze these refugees out of existence, but we are determined to give them room to breathe, and the best chance possible of continuing onward to a better life.

Please get in touch if you would like to work alongside us in Lesvos. We are particularly looking for longer-term activists who share our political principles, and drivers with cars [for full pitch and bank information for monetary donations, please visit NBK’s original post. —ed.].

With love, rage and solidarity always,

Your No Borders Kitchen crew

All images: No Borders Kitchen Lesvos

i. https://greece.iom.int/en/assisted-voluntary-return-and-reintegration-programs-avrr

ii. https://newsthatmoves.org/en/rumour-five-days-before-deportation/

iii. https://www.proasyl.de/en/news/greece-back-to-detention