Transcribed from the 8 July 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

The people with whom I speak, who went out to protest, call the beginning of those protests and the Syrian revolution a breaking of the barrier of fear. They say they lived in a regime of fear. They lived intimidated, unable to speak, unable to express themselves, for years. But people tasted freedom going out in the streets in 2011, and they say, ‘We tasted freedom. We cannot go back to being unfree.’

Chuck Mertz: There is plenty we do not know about the war in Syria. Unfortunately, there’s plenty we do “know” about the war that is just plain wrong, and maybe—just maybe—we don’t know what the hell is going on because nobody seems to be interested in what Syrian refugees say about the war. Luckily, somebody does, and she is our next guest. Political scientist Wendy Pearlman is author of We Crossed a Bridge and it Trembled: Voices from Syria. Wendy is a professor and award-winning teacher here at Northwestern University, specializing in Middle East politics.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Wendy.

Wendy Pearlman: Thank you so much.

CM: From the people you spoke with, could they imagine a Syria as it was before the revolution began, with Bashar al-Assad still in charge? Or is that something they believe just cannot happen, we cannot have Bashar al-Assad controlling Syria?

WP: The people with whom I speak definitely can’t imagine themselves living under such a situation. It’s a complex story, and it’s helpful to go back a bit and see the whole context of the unfolding of this war from its origins. As you mentioned, this book tries to tell the story of the Syrian conflict, from what life was like in Syria before the uprising to the present, exclusively through personal stories. I did all these interviews with displaced Syrians from 2012 to the present, across the Middle East and across Europe, and their individual stories really coalesce in a collective narrative about what Syria and the Syrian conflict is all about.

They really unify in painting a picture of an authoritarian regime that ruled for decades. Hafez al-Assad seized power in 1970; his son Bashar took over in the year 2000. This was rule by a single party that did not allow for any meaningful engagement or competition by other political parties, where there was a ubiquitous security force apparatus. Security forces, without any sort of accountability, could meddle in people’s lives: could take them away to political imprisonment in dungeons where they’d be disappeared and tortured and never heard from again; there was surveillance, there was a network of informants. People felt afraid to speak about politics sometimes even in their own homes. They had a sense that this was a place where there was no freedom: no freedom of expression, no freedom of association, no rule of law, no accountability; where one family ruled and there was nothing you could do to try and remove them and have other people rule; where those with power abused it almost without limit; and where those without power—your average citizen—really couldn’t do much about it.

That is the picture that they paint of what Syria was like up until 2011. The opening entry of the book is from a drama student who says, “In Syria before, a citizen was just a number. Dreaming was not allowed.” No freedom, no rights, no dignity, and no horizon for a possibility that citizens could achieve—or even imagine—anything better.

As we know, Syrians went out to protest with the backdrop of the Arab Spring—first tens and then hundreds and then thousands and then millions went out into the streets calling for change. First calling for reform: calling to lift this emergency law that allowed security forces to commit all sorts of abuses with impunity; calling for the dismissal of some particularly abusive and corrupt governors; calling for the opening up of the system. When the regime forces responded to those peaceful protests by killing, arresting, and injuring unarmed protesters, gradually people increased their demands, calling for regime change, reaching the sense that there was no way of working with this regime. It had too much blood on its hands, it showed too little regard for their lives. People got to the point, after several weeks, of feeling like there’s no solution but simply to call for the overthrow and the collapse of this regime.

After many months of enduring regime crackdowns, eventually the opposition took up arms, at first defensively—to protect themselves from what they saw as a regime crackdown—and then eventually carrying out more offensive operations. What began as an amazing show of people power, of unarmed protesters of all walks of life going out into the street, risking their lives to call for change, evolved into a war that had components of being a civil war—of Syrians fighting Syrians—and then increasingly became this multidimensional, penetrated regional war with regional actors, international actors, and the emergence of Islamist groups with fighters from all over the world fighting with agendas and goals and ideologies that were extremely different than what those first Syrians went out into the streets calling for. It evolved into this horrific, brutal destruction that we see today.

The people with whom I speak, who went out to protest, call the beginning of those protests and the Syrian revolution a breaking of the barrier of fear. They say they lived in a regime of fear. They lived intimidated, unable to speak, unable to express themselves, for years. They said they were raised to submit themselves to this cruel authoritarian regime, but then they went out into the streets to call for change, and it is difficult to imagine going back to rule by fear, going back to having to keep your mouth shut, to not being able to raise your head, to not being able to say no. People tasted freedom going out in the streets in 2011, and they say, “We tasted freedom. It’s difficult to go back to being unfree.”

For them, the idea of going back to live under Bashar al-Assad is going back to being unfree. And for the people I met, it’s just impossible to imagine doing that. It’s too painful. It’s too dehumanizing.

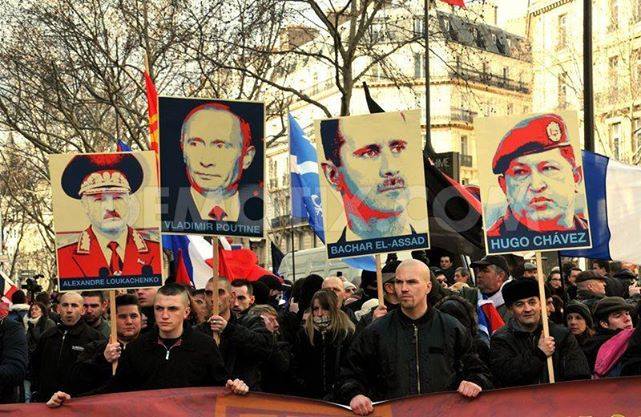

At this point, very sadly, the US and international powers are more and more accepting of a reality that, after so many deaths and so much destruction, means the continuation of the Assad regime. The real problem, they say, is ISIS. After all Syrians have suffered and sacrificed, maybe it’ll just be the Assad regime again, ruling through fear and intimidation and violence.

It’s difficult to trust in the intentions of the Assad regime, no less its backers. It’s hard to be optimistic these days.

CM: How much has Bashar al-Assad been able to rebuild that barrier of fear that the revolution took down? Or can that barrier of fear, once it’s down, never be rebuilt?

WP: I wanted to think that once the barrier of fear was down it could not be rebuilt. I even ventured to write things of that sort in articles. But then I began to hear about regime-controlled areas in Syria: that includes Damascus, where the regime has always been strong; it includes areas that had risen up and considered themselves liberated from regime forces, by the rebels pushing out the regime and rebel forces ruling themselves, as in the city of Homs and the eastern part of Aleppo, which have now been retaken by regime forces with absolute brutality, by aerial bombardment, by besieging and encircling communities and not allowing any food or medicine to enter.

In the city of Homs, for example, people and fighters held out for years in the old city. They were surrounded, and no food could enter, no medicine could enter. There’s a long interview in my book with a fighter who was in the old city of Homs for two years. People got to the point where they lived on grass and leaves. They would go out and collect grass and leaves and boil them in water. They ate grass and leaves for about two years, until the point where they were so near starvation that finally regime forces coerced these rebel groups to surrender. They organized an evacuation, and those rebels walked out of the old city of Homs, got on buses, and agreed to be transported to another part of the country.

The regime has now retaken Homs, and the fear has returned. If you want to live in Homs and not be killed, not be arrested, you keep your mouth shut and you don’t even think of criticizing. You get by. The people there are living in that state again. People have either left the country, or they’re there and that’s their reality. In Aleppo, which was retaken by regime forces last December, it’s a similar situation.

There are parts of the country that are still under rebel control, in Idlib in the northwest and other places, where people can speak freely, where they can talk, where they can try to have self-governance councils to rule themselves. But it has been a long, brutal effort by the regime, with its backers Russia and Iran, to reconquer the country step by step through bombarding people until they flee; through surrounding and starving communities until they surrender. That’s been their strategy in community after community: in Homs, in suburbs of Damascus, in Aleppo and so forth.

And the world has largely stood by and watched this happen in the cities and villages and communities—one after another—where Syrians rose up and in many places succeeded in pushing the regime forces out, and held out as long as they could against unbelievable odds, risking starvation, eating leaves, having no medicine, dealing with daily bombardment, holding out as long as they could until regime forces gradually took over again.

Even with this new ceasefire there are some who fear that the regime has no intention of any real peace; that it uses these ceasefires in order to alleviate pressure, to redeploy forces from one part of the country to another part of the country; that it takes advantage of “lulls” in order to regroup and restrengthen, just waiting for the next offensive where it will take back a major area with more strategic value.

It’s difficult to trust in the intentions of the Assad regime, no less its backers. It’s hard to be optimistic these days.

CM: You write that the goal of your book is to explain the Syrian uprising, war, and refugee crisis and “lay bare, in human terms, what is at stake.” And maybe that’s the part that outsiders do not realize: what is at stake in Syria. The Syrians we’ve spoken with have said that they still want a single Syria—the multicultural, multi-ethnic, multi-religious state—to exist. Is that what the Syrians you spoke with said was at stake, the idea of a multicultural state existing within the region? Or is there something even more?

WP: There is definitely the idea of a single, complete, multicultural, multi-ethnic, coexisting Syria. What’s also at stake is the human quest and drive to live in freedom. People who identified with the revolution saw it as a revolution for dignity, for freedom, against a regime in which people felt like they could not speak their minds, where they were not respected, where they had no rights, they had no protections. They were really going out and fighting for that freedom. The first words that people said when they went out in the streets were Freedom and Dignity.

That’s what I think was most at stake: people wanting to live in a place where they can achieve their aspirations, where they can feel safe from arbitrary abuses and violations of rights, where if you are arrested you have a trial and an opportunity to defend yourself, not thrown in jail forever without even a charge, to say nothing of a trial.

When the revolution first began, there wasn’t really much talk about multiculturalism and so forth. Many Syrians take that for granted. The Syrians I spoke with today say, “We were always a multi-ethnic, multi-religious society, and it wasn’t that big of a deal for us.” People like to say things like, “You didn’t even know what religion your friends were.” Syrians with whom I speak talk about the multi-religious, multi-sect nature of Syria with tremendous pride, and really with nostalgia. There is a pride that Syria was a place where people of all religions lived together and it just wasn’t that big of a deal. You had your religion, and people respected others, and it wasn’t anything to talk about or fight about, it was just coexistence and mutual respect.

It was one thing to suffer political indignities when at least you felt like you could feed your family and have access to work and so forth. But when you are both hungry and you feel like your dignity isn’t respected, then there’s really little to say in favor of this regime.

Of course, during the course of the terrible war, sectarianism has taken on a new tone. Many people blame the regime for what they see as a deliberate strategy of sectarianization: that the regime used sects in an effort to divide and conquer its own population by setting groups against each other, by trying to foment distrust as opposed to the kind of trust that would bring people together in a united front to fight for a civil, free state; that it used sectarianism as a way to try to discredit and slander the opposition and the revolution by accusing them of being terrorists or Islamic fundamentalists or Saudi-funded jihadists and so forth, at a time when it was young people going out and calling for freedom without any words about religion or any sort of religious agenda.

The regime, from the very start, used accusations of extremism and sectarianism, and accusations that the revolution was the Sunni majority rising up, and that religious minorities should be afraid, that this was a community that was going to rise up and try to create an Islamic state, and it would be harmful and dangerous for religious minorities. That was the kind of rhetoric it used from the beginning, in a dirty attempt to support and bolster its own rule.

The revolution, from the beginning, always fought against that rhetoric. There are signs and slogans and songs you can see on YouTube, of people calling out and saying, “Neither Islamism nor Salafism, My Revolution is Freedom,” and “To our Brothers, O Syrians of All Religions, Stand With Us!” In other words, “This is not about sectarianism, we’re against sectarianism, we want a place where all citizens can be free and be respected.”

Activists really went to heroic lengths to try to demonstrate that their cause had nothing to do with religion or religious intolerance. But the regime played a dirty game in trying to paint it otherwise.

CM: You write, “Neoliberal economic reform opened the country to new consumer goods and commercial possibilities. Many in the urban middle- and wealthy classes rejoiced in access to novel comforts. Unleashed without political accountability or oversight from an independent judiciary, however, privatization and trade liberalization allowed corruption to reach unprecedented heights.”

How much is the Syrian revolution an uprising against neoliberalism?

WP: I think in some ways, the neoliberal reforms that were made in the 2000s were the straw that broke the camel’s back. The first part of the book are stories about life under the regime of Hafez al-Assad, who ruled from 1970 to 2000, and the stories they paint there is of a security-centric, single-party, tough regime that was also a regime with a state-dominated economy. The Ba’ath Party prided itself on socialism, and Assad came to power building on a previous Ba’ath Party regime in Syria in the 1960s that gave out lots of subsidies and services to peasants and workers, and made a huge investment in a state public sector. The state became the major employer of the country—it brought a huge number of jobs, but also brought electricity to the countryside, free education, free healthcare and so forth.

A lot of those social reforms, that basic redistribution economics, made a lot of people’s lives a lot better and opened opportunities that especially poor communities in rural areas would not have otherwise had. But unfortunately it was unsustainable. The state simply could not afford to sustain this huge, bloated public sector, and it was just trying to disguise the lack of a more productive, dynamic economy that could produce prosperity. It was just putting more and more people on the state payroll and then paying them such meager wages that someone working as a civil servant could barely pay the rent. People had to work as taxi drivers or have other jobs in addition.

So there was a ticking timebomb, as far as the economy went. Then Bashar al-Assad came to power in the year 2000, recognized these economic problems, and tried to resolve them through a shift towards privatization and neoliberal reforms, a shift from a state-dominated economy to a market economy. And as it says in the portion you just read, since this was done in an environment where there was no rule of law and no judicial oversight and no political accountability, it essentially created a situation in which the Assad family and other crony capitalists around them got monopolies and exclusive, uncompetitive contracts, and a handful of people got really rich by owning all of the cell phone providers or all of the media outlets, or having the first crack at all of the contracts for building.

A handful of families, through a small network of these collusive business-government arrangements and relationships, got really, really wealthy. And at the same time, that bedrock of services and subsidies, of free education and free healthcare, of investment in infrastructure, got rolled back more and more, so that the bulk of the population saw their lives get worse and worse. The poor got poorer, free public education became less and less meaningful and valuable, with hundreds of students stuffed into classrooms and so forth. The poor got poorer and their opportunities began to shrink while a few got very wealthy with a new kind of conspicuous wealth. In the eighties and nineties, with a state-dominated economy, there just weren’t that many products on the shelves. One expression was, “Even Hafez al-Assad himself doesn’t have bananas.” He can’t get that kind of fancy import. In the 2000s, though, there was Starbucks and fancy brands.

Some got wealthy, and then there was an affluent, aspirational class that also rejoiced in having new opportunities and fancier brands and being able to go out at night in fancy cafes in Damascus and Aleppo that simply weren’t available in prior years. But the bulk of the population got poorer and poorer.

What really spurred the revolution, though, was this foundation of political grievance, of people wanting rights and liberties and to be able to choose their own government and rule themselves. The real bedrock, I think, was political grievances. But the fact that they didn’t have those political rights, and then over the years they also didn’t have the economic services and subsidies and opportunities they once had, really tipped things over the edge. It was one thing to suffer political indignities when at least you felt like you could feed your family and have access to work and so forth. But when you are both hungry and you feel like your dignity isn’t respected, then there’s really little to say in favor of this regime under which you live. It can push people to say, “Enough. We want something better.”

One other complication that some people talk about is the fact that there was a drought in areas of Syria, from 2006 to 2009 or so, which caused much more additional hardship, especially in rural areas, with some farmers needing to abandon their fields and their livelihoods in agriculture because there simply wasn’t water. That was not just a natural catastrophe of lack of water, but also government mismanagement, a failure to bring proper irrigation.

The people who went out into the streets did so risking their lives. When I talk to Syrians, again and again they say that when you went to a protest, you did so prepared never to come home.

There’s always this link between political problems and economic problems—either economic problems or political problems alone might not be enough to bring people to risk their lives calling for change, but the two of them together form a very powerful impetus that can bring people to say enough is enough.

CM: I hate to do this to you, Wendy, but I get emails from listeners, and they blame different things for the Syrian war. I really want to clear this up, and you clearly are versed in this. So back in April 2011, the New York Times reported, “A number of the groups and individuals directly involved in the revolts and reforms sweeping the region, including the April 6 Youth Movement in Egypt, the Bahrain Center for Human Rights, and grassroots activists like Entsar Qadhi, a youth leader in Yemen, received training and financing from groups like the International Republican Institute, the National Democratic Institute, and Freedom House, a non-profit human rights organization in Washington, according to interviews in recent weeks and American diplomatic cables obtained by Wikileaks.”

And also back in 2011, the Economist had a story on all the conspiracy theories within the Arab world of the West trying to overthrow everyone in the region, reporting, “The story goes something like this: Western powers, led by America, are realizing their long-held aim of dividing and weakening the Arab and Muslim worlds.”

To you, how much was the Arab Spring about people in the region yearning for change? Or was it about the US, the CIA, and Western powers yearning for regime change?

WP: It was absolutely about people of the region yearning for change. The people who went out into the streets in many of these countries did so risking their lives. When I talk to Syrians, again and again they say that when you went to a protest, you did so prepared never to come home. You could be killed on the streets because there were police there shooting; you could be beaten; you could be arrested, taken away—there are reports now estimating tens of thousands of Syrians have been tortured, imprisoned, disappeared, and never heard from again. Not only could you possibly be arrested on the street, but even if you made it home from the demonstration safely, you could get a knock on your door the next day because someone saw you in a demonstration, and now they’re coming to pick you up.

People talked about how there were undercover informants or security agents mixed among them in the protests, there to take pictures, to know who was who, and to arrest people. I heard a story from one young man who talked about a friend of his who took part in a protest, linked arms with somebody on the right and linked arms with somebody on the left (because people would dance and sing and celebrate) and these two people slowly led him to a police car, where they put him in and drove him away. They were undercover police agents.

There’s a story in the book about one man who was on the shoulders of another protester, singing and dancing and chanting, and then he got pulled in for interrogation with the secret police and they showed him the film, and it turns out he was on the shoulders of somebody who was an undercover agent.

I tell these stories—and there are so many more—just to emphasize the degree of danger, mortal danger, that people were confronting and accepting to go out and fight for change. This is no Western plot, no CIA plot. These are people getting to the point where they’re willing to risk their lives for their own communities and their own selves to live as humans, free beings.

There might have been cases of US-sponsored training or support. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s there was a big push for US programs of democracy promotion. But I don’t think that constitutes a CIA regime-change plot. There were millions of dollars from the US government and from US foundations and US civil society organizations spent on the idea that in order to promote democracy, you should promote civil society. That means youth groups and women’s groups and discussion circles and forums and newspapers and all of these social capital ways that bring people together because that’s a way to enrich the democratic capacities of countries. That’s not talking about regime change. It was an idea of investing in civil society as a way of promoting democracy.

Under that rubric, money and support filtered into human rights organizations and civil society initiatives throughout the Middle East and throughout the world. Some of the organizations that maybe later took part in the Arab Spring very well might have participated in a training or gotten some sort of a grant, or gotten a computer that was given by USAID or something. But that was under the rubric of democracy promotion, not “regime change.”

There are a lot of studies, actually, that talk about how US democracy promotion activities were not seeking regime change, but the opposite: stabilizing regimes, creating a status quo in which it appeared that the US was promoting democracy but with which ruling dictators were quite comfortable. They thought they had it under control. They had elites in their pocket, they co-opted who they needed to, they used violence whenever they needed to, they could rig elections and so forth. So it didn’t matter if there were hundreds of thousands of dollars coming in from USAID for women’s groups or youth projects. Hosni Mubarak was quite comfortable with that, as were dictators in other places.

If “moderate” means not upholding any sort of ideology of religious extremism, seeking a political solution that respects religious difference, calling for rule of law, calling for a civil democratic state in which all people can be citizens and have their rights respected regardless of religion—if that’s what moderate means, I meet dozens of moderate Syrians every day.

All of those programs were criticized in the 1990s because they didn’t seem to be leading to democracy. Indeed they seemed to be undergirding and sustaining and contributing to the relative stability of the status quo. So I think it’s quite ironic that, once people went out in the streets in 2011, we would suddenly look back and say, “Oh, you see, all of that American money was part of a Western plot to overthrow regimes.” At the time people were saying the exact opposite.

Really, the US was quite comfortable with authoritarian regimes in the Arab world. Hosni Mubarak in Egypt was a very important ally of the United States, as was the president in Yemen and other places. We worked with the authoritarian president in Yemen because he was on our side in fighting Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula and so forth. You can see our very warm relations with Saudi Arabia and other Gulf dictatorships. The United States does not have a history of trying to overthrow Arab authoritarian regimes. The opposite. We’ve been quite comfortable with them as long as they have maintained relative stability and worked with us in “fighting terrorism.” We’ve never been so concerned about the violations of human rights that they commit against their own citizens.

I would be more likely to accuse the US of not doing enough to really stand up to authoritarian regimes than to accuse the US of plotting to overthrow them. I think the Arab Spring took the United States totally by surprise, and it did so precisely because it was ordinary people, many of whom had no contact with any of these civil society initiatives, simply saying enough is enough. They surprised us with their courage and their sense of having no other choice and nothing left to lose but to go in and call for something better. I absolutely see the Arab uprisings as people-powered movements, as grassroots movements. The US was twenty steps behind the people on the ground who just pushed forward with something that they needed to do for themselves and their communities.

CM: One last question for you, Wendy, and as we do with all of our guests, our final question is the Question from Hell, the question we might hate to ask, you might hate to answer, or our audience is going to hate your response.

When we have had guests on about Syria in the past, nearly every time we get someone telling us or emailing us or leaving a message on Facebook or Twitter that there is no such thing as a moderate that is a non-ISIS or Al Qaeda-affiliated Syrian in the opposition. To you, what explains that despite the existence of revolutionary coordinating committees and organized resistance and opposition to Assad that has now been going on strong for six years (you still say that there are rebel-held areas of resistance still within Syria)—what explains this belief that’s widely held that there are no moderate Syrians? Or is part of the problem that we’re using the phrase “moderate” Syrians?

WP: What explains why people say there are no moderate Syrians? My first response is intellectual laziness. I think it is just a cop-out. They’re not doing their homework. I don’t even know what “moderate” means. But if moderate means those people who are not upholding any sort of ideology of religious extremism, who seek a political solution that respects religious difference, who call for rule of law, who call for a civil democratic state in which all people can be citizens and have their rights respected regardless of religion—if that’s what moderate means, I meet dozens of moderate Syrians every day. They’re not just on the ground in Syria. Many of those who have been displaced continue to be involved in amazing initiatives.

I’m meeting this week with an organization called Citizens for Syria. There’s another one called Adopt a Revolution. There are dozens of civil society organizations, some now based in Germany, some on the border of Turkey and Syria, throughout the region. There are many Syrian-American organizations based in the US that are doing amazing work, still struggling for what they hope is a free Syria. And when they say “Free Syria,” it has nothing to do with Islamic law or an Islamic state or any policies that would impose a religious agenda on anyone else.

Of course, in war, when people are brutalized and subjected to horrific violence, some people become radicalized. For sure. I would encourage all of your listeners to think: what would you do if you lived through years under bombardment? If you lived for years in which a national and a world media misrepresented who you are and accused you of goals and rhetoric and ideologies that you don’t actually uphold? If you can’t access food, and a loved one was killed, and there’s nowhere you can appeal, and members of your family were arrested and you’ve never heard from them again, and you don’t even know if they’re alive or dead?

It’s hard to say where these conditions would drive each of us. I think it might drive everyone to a different place. But it will certainly drive some people to want revenge and to embrace violence, and it is heroic that so many Syrians under these conditions still call for forgiveness, call for coexistence, and don’t have hearts filled with hatred. All people react to these types of circumstances differently.

There are hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Syrians who believe in coexistence, who want freedom and democracy. But every day they are slandered and bombarded, arrested and disappeared and killed. There might be fewer and fewer of them who are in a situation to rebuild the country in that direction. It’s a shame. Many of those “moderate” Syrians were the first to go on the streets, which also means they were the first to be killed. They were the first to be arrested. They were the first to be disappeared. We will maybe never even be able to write the histories of all of those moderate Syrians who were systematically removed from the scene.

Some people say that Bashar al-Assad wants that reality. He wanted to remove the moderates so he could say, “See? It’s only me or the extremists. It’s me or ISIS. It’s me or Al Qaeda.” Moderate Syrians were the greatest threat to the regime. He needed to get rid of them in order to promote the narrative that would allow him to be seen as a legitimate option.

So I would say there are still “moderate” Syrians, many of them. If their numbers are fewer, we need to ask ourselves why. Where did they go?

CM: Wendy, thank you so much for being on our show this week. This is one of my favorite books I’ve read so far this year.

WP: It’s been such a pleasure. Thank you so much for the opportunity.

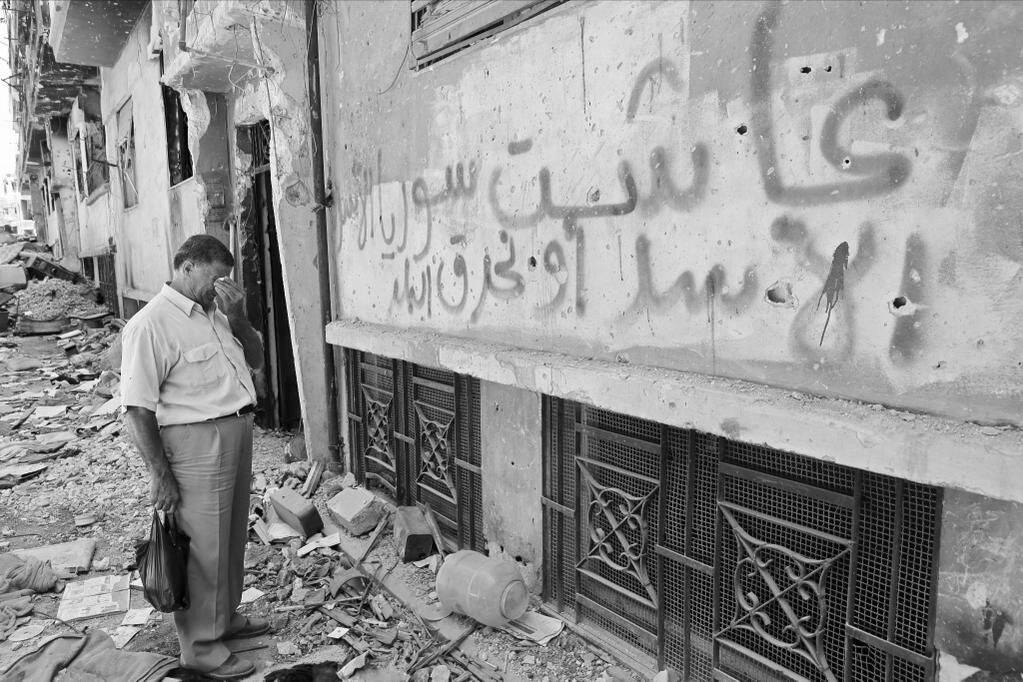

Featured image: Homs. A man weeps in front of shabeeha graffiti: “Assad or we burn the country.”