At the Core of the War in Syria

by Bente Scheller for the Heinrich Böll Foundation

5 October 2017 (original post)

No matter how complex and religiously-driven the conflict in Syria may seem, its basic constellation is this: a regime with powerful allies is waging a war of annihilation against wide swathes of its own population. How could it get to this point? And what can we do?

Note from the Heinrich Böll Foundation: This article is based on a talk given by Dr. Bente Scheller, director of our Beirut office, in Munich on 17 September 2017.

Those of you who visited Syria before 2011 may tend to remember your journeys as fondly as I do: A country in which buildings from a variety of eras bear witness to a long history of many peoples and religions. The old town of Damascus in which the Umayyad mosque rises atop the foundations of the ancient Roman temple of Jupiter; an environment characterized by tradition, in which people, between prayer calls and church bells, go about their everyday lives which in turn could be thought to have emerged from the tales of the Arabian Nights.

Engulfed by the scent of jasmine and cardamom coffee, a foreigner can easily forget about the dark side of Syrian life. Syria was not only a country in which you could positively feel the heartbeat of thousands of years of ancient societies, but also a state in which the most enormous security apparatus in the Middle East virtually strangled its citizens.

The widely praised peaceful coexistence of religions was certainly no feat of Hafez al-Assad, who had gained hold of power in the country by means of a coup in the 1970s. It was rather a characteristic of Syrian history, without which so many small and minuscule communities of different religious affiliations could never have developed and persisted.

Yet his grasp for power presented a religio-political issue for Hafez al-Assad. As is common with dictators, he was concerned with assuming the appearance of legitimacy—however, while the Syrian constitution states that the president must be of Muslim denomination, Muslims were conflicted over whether the religious community to which he belonged, the Alawites, were part of Islam.

As much as he laid emphasis on the pan-Arab nationalism propagated by the Syrian Ba’ath Party, the crucial question remained: how should he deal with this religious matter?

Hafez al-Assad is succeeded by his son Bashar – and history repeats itself

This was Hafez al-Assad’s solution: to have a religious decree fashioned by Muslim scholars which declared his religious community Muslim. Simultaneously, he disallowed any discussion of religion or political-religious questions such as whether any one religious group enjoyed privileges or was oppressed.

Not everyone supported Hafez al-Assad’s politics. Expropriations, for example, which were enforced on the basis of socialist-tinted politics and the disadvantaging of certain territories, caused tensions.

When, towards the end of the seventies, a first major uprising formed for this reason, the regime crushed it with armed force and Hafez al-Assad branded the movement “Islamist.” Although the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood was the driving force backing the rebellion in the beginning of the eighties, it was by no means only its members who were met by violent suppression.

Syrian human rights lawyer—of Christian faith—Anwar al-Bunni, who now lives in Berlin, experienced the insurgency and its suppression in Hama, the city center of which was leveled to the ground at the time. Widespread arrests caused all men fit for military service to be put under general suspicion. Even back then, it was enough to be in the wrong place at the wrong time for a person to be executed on the spot or to be abducted.

The suppression of the uprising by Hafez’s son and successor Bashar al-Assad which commenced in 2011 is a repetition of history, only at a much greater scale.

As soon as the demonstrations began to form, Bashar al-Assad denied the insurgents any form of humanity: they were, in his view, “microbes”—an evil that had overcome Syrian society and required eradication. Not long after, they were declared “terrorists”—a term that also entices people in Western societies to abandon constitutional thinking and to justify any means.

The majority of insurgents were without doubt of Sunni faith—simply because the majority of the Syrian population, approximately seventy percent, is also of Sunni faith.

The protesters in Syria demanded only what is a given for us in Germany

However, the demands brought forward by the insurgents were neither of a religious nor of a secular nature. They were humane.

Those who, in the hundreds of thousands, summoned the courage to take to the streets were neither controlled from the outside nor did they have a religious agenda. They demanded what is a given for us in Germany: dignity, freedom and justice.

The women and men protesting chanted “silmi, silmi”—“peaceful, peaceful”—while they raised their hands to the sky to show that they did not carry any weapons. And they were met with the regime’s bullets.

Bashar al-Assad mocked the victims during his parliamentary speech at the end of March 2011. And yet, in order to impart its message, “do not dare challenge the powers that be,” on the population, the regime quickly discovered even more cruel methods.

One of the first casualties was thirteen-year-old Hamza al-Khatib. The secret service arrested him amid a demonstration and, a few days later, handed over his brutally mangled corpse to his parents. A child, tortured to death by the secret service.

With that, the regime revoked the unwritten pact that at least those who do not pose an essential threat to its power would be spared. A certain degree of security and stability, a bare minimum for the sake of which many Syrians had been prepared to accept authoritarian rule, was therefore no longer given.

This is a prime example of the fact that autocrats are not only no guarantor of stability, but are its natural enemy: due to their lack of democratic legitimacy, they live off turning any opposition to their rule into a threat to society—at best, a threat that also strikes a nerve in democratic states. Such as terrorism. Autocrats do not stick to the rules, they bend them. Their rationale is despotism. They thereby disqualify themselves as reliable partners of constitutional systems.

Because prominent Christians and Alawites were among the ranks of the Syrian resistance, because many purposefully nonviolent activists had attained a certain reputation within and outside of Syria, it was of much greater importance for the regime to silence them than to deal with the protagonists—who, it bears mentioning, only started to arm themselves after six months.

One of our partners, internet activist Bassel Khartabil, was incarcerated and tortured to death

Perhaps you are familiar with Padre Paolo Dall’Oglio. Paolo was an Italian Jesuit priest who had settled in the Deir Mar Moussa monastery. There he founded a community which took it upon itself to restore the seventh-century cloister and to transform the place into one of interfaith dialogue. Here, one would meet young Syrian men and women of various denominations who would work and meditate together. Looming majestically above the scraggy mountains, Mar Moussa became an emblem of Syrian diversity and lived cooperation that was tolerated—though also regarded with distrust—by the regime.

Padre Paolo was an impressive personality. After decades of working in Syria, he spoke fluent Arabic, and never failed to speak his mind when it came to decrying injustice. At the beginning of the revolution, he called for a shared solution and for people to be vocal against violence.

As a consequence, the Syrian regime expelled him from the country. Syrian members of his community were arrested.

Activists in Syria face danger from all sides. Whoever is persecuted by the regime is just as persecuted by the so-called Islamic State, or ISIS. In 2013, Padre Paolo traveled to Raqqa in order to negotiate with ISIS, a force that cares little for conversation. It is here that he was abducted. To this day, he remains disappeared without a trace.

In 2012, nonviolent internet activist Bassel Khartabil, a partner of our office, was among those arrested and tortured to death within months. At the same time, the regime was discharging many Islamist detainees.

These had only ended up in prisons in the first place because the regime itself had once recruited them as fighters for Iraq in order to perpetrate attacks against the American occupation there. Still, most of the people who fell victim to their attacks in Iraq were not occupation soldiers but Iraqi men, women and children.

The regime is not afraid of Islamist terrorism. Assad uses it for his own purposes

The jihadists who returned from Iraq were incarcerated by the Syrian regime. The regime regarded it as too risky to have these battle-hardened extremists at large in its own country. However, in a time of political crisis, they worked in its favor by adding vigor to the regime’s narrative that it was dealing not with a revolution but with an attempted Jihadist coup.

Islamist terrorism has by no means been what the regime fears most, but rather is what it has learned to brilliantly exploit—something it continues doing to this day.

It was not until the so-called Islamic State proclaimed its caliphate that a counterpart came into existence beside which the Syrian regime—which itself had forced millions of people to flee their homes, had killed hundreds of thousands and had disappeared tens of thousands more—appeared to be the “lesser evil.”

Nowadays, people who shy away from criticizing the regime typically do so while referencing religious minorities. Assad as the guardian of Christians has become a truism. How far have our standards declined if we accept Mafia-like sponsorship without question?

Chartered rights are what protect minorities. What we see in the Syria of today is the exact opposite. When armed groups set their sights on the Christian town of Maaloula in which to this day Aramaic—the language of Christ—is spoken, the regime chose not to protect it at the town gates but instead positioned itself between churches and monasteries, with aim of provoking headlines to the effect that the opposition was specifically targeting Christian institutions.

Regime forces were withdrawn from the characteristically Islamist city of Salamiyeh in order to exert pressure on its population to send their sons to join the military service. Minorities have no rights in Assad’s Syria. Protection is granted or withdrawn as an act of grace, depending on the current political expediency.

To my knowledge, the Syrian regime has not put itself forth as secular. Yet, with the emergence of ISIS, it seems to me that the regime is being increasingly perceived as secular in Western countries. The paralysis which befalls Western societies when confronted with ISIS leads to this seemingly so obvious and simultaneously problematic conclusion.

Assad’s regime abuses and kills like ISIS – only at a much larger scale

The Syrian regime’s propaganda in many ways contains religious references, starting with their slogan “Assad forever,” which was later extended to “Assad forever and the time thereafter”—a clear reference to the afterlife. Or, as chanted by Assad supporters: “With our soul, our blood, we defend you, Bashar.”

I have not watched only the perfectly staged execution videos released by ISIS which were recorded for Western eyes with the aim of spreading fear. I have also seen hundreds of videos by the regime’s henchmen who have proudly filmed their abuse of prisoners.

One element that constantly recurs is that prisoners, while being abused, are shouted at: “Say it! ‘There is no God but Bashar!’”—a derivative of the Muslim creed ‘There is no God but Allah.’ One need not be of Muslim faith, or even a particularly religious person at all, to feel the humiliation being heaped on the defenseless victims.

Barbarism is what ISIS is rightly known for. However, in reflection of all that I have seen not only on YouTube but from the reports of former detainees in Syrian prisons and former employees of Syrian hospitals (some of which are part of the Syrian torture apparatus), I am left only with this: it is a challenge to identify a form of abuse or killing that is deployed by ISIS and not also by the regime. The latter simply does it on a vastly larger scale.

There is no shortage of evidence for these atrocities. A military photographer who was tasked by the regime with taking pictures of those tortured to death in Syrian prisons smuggled 55,000 photographs out of the country, depicting more than 6,700 slain people. Nobody should be forced to see these images. However, it is of much greater importance to establish: nobody should be forced to suffer what has been inflicted on the people in these pictures.

In 2004, the Syrian regime signed the international Convention against Torture. In 2013, the Syrian regime joined the international Convention against Chemical Weapons. The regime is regularly and systematically in breach of both. That is no trivial offense and also, in my judgment, not a matter internal to Syria. It constitutes a serious breach of international law which we should view with deep concern.

As soon as the air strikes grind to a halt, people return to the streets with their demands: dignity, freedom, justice

International conventions set limits on the rights of the more powerful protagonists. They protect the weaker ones. If we allow the conventions to be consciously and frequently breached, we thereby not only abandon our values and question our own moral integrity, but also endanger our security and the security of many others.

Even when what ISIS seems to stand for and what other Islamist protagonists seem to strive towards instills fear in us, we should not be tempted to understand this situation as a religious conflict, as a war that draws from religious convictions that are foreign to us and that we struggle to comprehend, and therefore assume we cannot speak up for humanity and human rights.

This is a conflict which over the course of years has increasingly exhibited the characteristics of a proxy war between international militaries and political protagonists.

This is a conflict that has been religiously charged.

Yet, at its core, this is a conflict that pursues interests comprehensible to us: a conflict for power and participation in profoundly mundane processes. And furthermore with protagonists who continue to demand what is closest to us: dignity, freedom, justice. Even in the face of an increased emergence of Islamist rebel groups, that has remained unaltered.

During the (few) moments in which negotiated ceasefires prevail, the following scene can be observed in hundreds of localities: As soon as the air strikes of the regime and its allies grind to a halt, people take to the streets with unchanged demands, even in regions that, for years, have been starved and riddled by bombs.

Most of the oppositional areas in Syria suffer a double threat: while ISIS and the Syrian regime largely stay out of each other’s way, they instead both run riot on the Syrian opposition. As soon as the opposition has a moment to catch its breath, it drives out the Islamists, be it ISIS or, as recently happened in the locality of Saraqeb, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (the successor of Jabhat al-Nusra, itself close to al-Qaeda).

As complex as the situation in Syria may seem, its basic constellation is clear: a regime which not only holds sovereignty over the airspace and the air force, but which also counts powerful international protagonists as its supporters, is waging a war of annihilation against wide swathes of its own population.

The very least we can do for people in Syria

It may be difficult to imagine a different Syria and even more difficult to show how to get there. The opposition is fragmented and as such is unable to present any viable alternatives.

However, the conclusion cannot be to remain uncritical of the regime’s systematic displacement of Syrians and—in the words of human rights activist Stephen Rapp—the “killing on an industrial scale.”

The very least we can do for Syrian civilians—who continue to make up over ninety percent of the Syrian population—is not to demean the active democratic forces among them.

If, politically, we are unwilling or unable to end the war, we should acknowledge that we at least have a responsibility to those who were forced to flee. And yet, it is our policy to coerce the people who come in search of protection into committing “illegal” acts: whoever wishes to find security is often forced to pay smugglers and put their life at risk once again during the unsafe journey across the Mediterranean.

Only recently, a television appearance of a Syrian army general, Zahreddine, was aired in Germany in which he said, accompanied by the derisive laughter of surrounding soldiers: “My advice to those who fled Syria to another country is to never return. […] We will never forgive nor forget.” To “not forgive” that they fled war and violence? That is a clear indication that those who have fled cannot safely return to Syria.

Based on my own studied observation of Afghanistan and also on our office’s work in Iraq I can say: the Syrian population’s will to govern itself, to not lose heart when faced with military superiority, and to create alternative civil structures is exceptional. For that, many Syrian activists have paid with their lives. And we have largely looked on without taking action.

Those remaining deserve not to be brushed aside as irrelevant or non-existent, and for us not to lose sight of the true perpetrators.

It is not the Syrian revolution that brought about death and ruin to the country, it is the Syrian regime’s brutish response.

The first placard those entering Syria see reads: “Welcome to Assad’s Syria.” That is precisely how the Assad clan perceives the country: not as a state of which they have been temporarily entrusted and therefore the citizens of which they carry the responsibility to safeguard, but instead as private property. Private property that they would rather destroy than abdicate their power. That is dangerous.

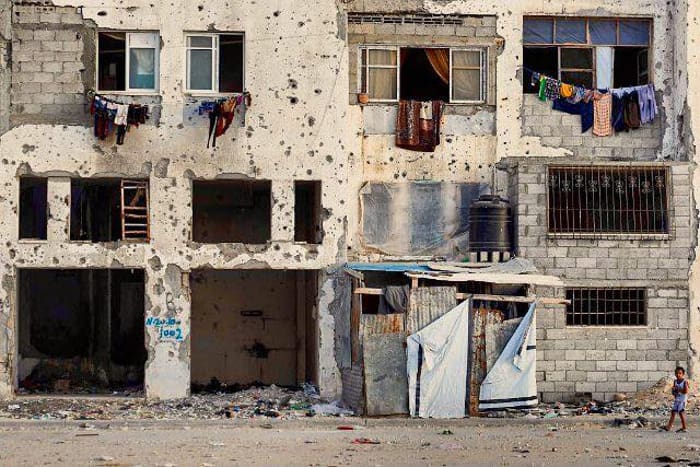

Featured image: from The Restless Earth, an exhibition about migration at the Triennale 2017 in Milan with artists from Syria. Source: MANYBITS (flickr) via Heinrich Böll Foundation