Transcribed from the 2 December 2017 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

When I began reading Franz Fanon, C.L.R. James, and Cedric Robinson, I began to understand what I had taken part in with the special forces. I was just one among the latest generation of imperial soldiers of color who were sent out to the periphery to police the empire for US capital.

Chuck Mertz: Black liberation stands in defiance against the ravages of imperialism, no matter where imperialism raises its ugly head and no matter what nation’s shoulders that head rests upon. Here to tell us how a fight against imperialism is a fight for black liberation, historian Paul Ortiz wrote the essay “Anti-imperialism Is a Way of Life: Emancipatory Internationalism and the Black Radical Tradition in the Americas,” which is included in Gaye Theresa Johnson and Alex Lubin’s collection Futures of Black Radicalism that we featured on last week’s show and will be featuring in interviews throughout the month of December.

Welcome to This is Hell!, Paul.

Paul Ortiz: Thank you so much for having me, it’s great to be here.

CM: It’s really great to have you on the show.

You write, “I had to leave the United States to understand it. As a sergeant in the US special forces in Central America in the mid-1980s, I encountered Augusto Sandino. I saw him everywhere I went. Representations of the Nicaraguan revolutionary’s visage and murals of his guerilla comrades etched into walls with Sandino’s sayings were ubiquitous in the region. Governments that had aligned themselves with US interests viewed Sandino’s words as seditious. No sooner had the policía scrubbed Sandino’s injunction ‘Come, you pack of morphine addicts, come to kill us in our land’ from one side of a building, descending artists would write on the other side, ‘We’ll go to the sun of freedom or to death.’”

Last week one of our guests was Suzy Hansen. She’s the author of Notes on a Foreign Country: An American Abroad in a Post-American World. In her book she writes about her travels to Turkey and Greece: “What continued to surprise me was that I kept learning from foreigners about my country, about America in Turkey and then about America everywhere else.”

How much better do you think outsiders understand the US than a typical US citizen?

PO: It really wasn’t until I delved into African-American history that I began to grapple with this question. I had been in Central America and South America in the special forces; I’d been a soldier of empire. But when I returned to the United States in 1986, I really didn’t have any way of making sense of my experiences. I didn’t know back then that there was such a thing as an antiwar movement. I grew up in a military town, Bremerton, Washington. If there was an antiwar movement there I didn’t know about it.

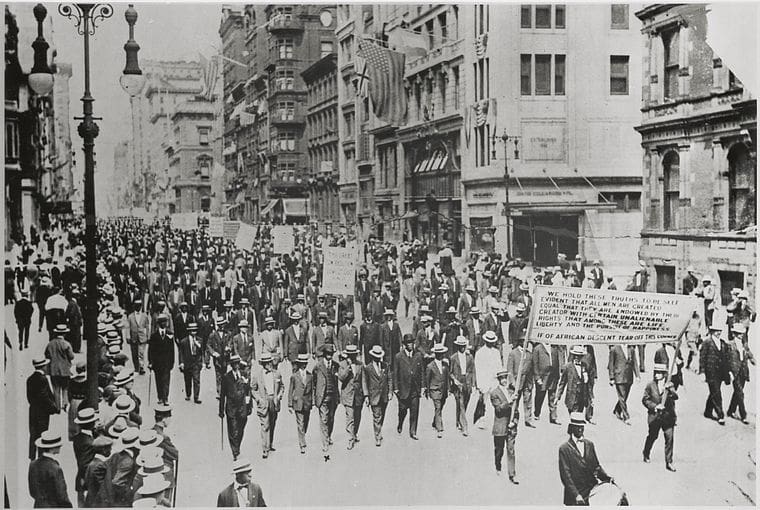

As for the passage you just referenced, I had started doing research into black history of the 1920s and came across all these amazing critiques in African-American newspapers of American imperialism—and not just critiques but positive, laudatory pieces about Augusto Sandino and many other anti-imperialists throughout not only Latin American but also Africa and Asia. In other words, African-Americans were seeing American imperialism in the 1920s, they were calling it out, they were not celebrating American intervention overseas.

What can we learn about this country from people overseas and in other countries? We can learn, finally, to see the United States through the eyes of the majority of the world’s population.

CM: How much, then, did your time in the military—maybe ironically—lead to your criticism of US military policy and the way that the US military is used around the world?

PO: For me it was the beginning. I mentioned I grew up in a military town. I didn’t grow up in any kind of left or radical tradition. I had some great teachers, though. I had teachers insist I read Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, John Steinbeck, people like that. So I had an awareness, but really going into the military at age eighteen I didn’t have a way to understand what I was taking part in.

That experience, though, was critical. When I got back to the United States and began reading Franz Fanon, C.L.R. James, and Cedric Robinson, I began to understand what I had taken part in. I was just one among the latest generation of imperial soldiers of color who were sent out to the periphery to police the empire for US capital. I came across other books as well. Smedley Butler’s War Is a Racket was a very important book for me. Here you have a marine corps general who at the end of his service realizes he’s been a “hired gun for capitalism”—those were General Butler’s words.

But really above all it was reading Cedric Robinson’s Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition which truly gave me some intellectual and social movement tools. Because I was also involved in social movements. I was organizing with the United Farm Workers. I worked with a lot of people who had been refugees from Central and South America and Mexico. And when I say refugees, I mean they were fleeing US military and trade policies. Cedric Robinson’s work was a way to understand how those processes of imperialism and racial capitalism (as he called it) worked, but also how people fought back—these resistance struggles really connect us to people from other countries. Until we learn those connections, we’re always isolated. We’re individuals. We’re disempowered.

We can be on Facebook and write wonderful tweets, but we can’t link up to broader struggles. That’s what I think this entire book Futures of Black Radicalism is about.

CM: To you, what explains why we know so little about our country, and those who do not live here know so much? Suzy Hansen talked about our dependence, here in the US, on the myth of American exceptionalism. Is it our dependence on myths like American exceptionalism that makes us turn a blind eye to the real problems the United States causes around the world?

PO: Yes. It’s a big part of it. Really since the election of Andrew Jackson we’ve been asking how we’ve arrived at such a debacle. Why do we have such seemingly lousy leaders? We’ve been doing this now for over two centuries. Every time we elect someone like Warren G. Harding, Polk, Cleveland, Bush, Trump, we keep asking the same question. How did we arrive at this disastrous juncture?

What I call the “soothing anti-depressant” of American exceptionalism blinds us to the fact that oppression, imperialism, and corruption have been integral aspects of our history. These are not aberrations. It might be that we have to give ourselves fairy tales to get up and look ourselves in the mirror every morning. But these are really crippling types of fairy tales. If you listen carefully to the black radical tradition and these struggles that have happened in the Americas, you come to a much more accurate rendition of our history.

No one in power is going to help us remember or teach us how to challenge their power. That’s why we have to do it on our own and in concert with each other.

America has not been that City on the Hill. Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison would have had no love for you and me. If Jefferson, Hamilton, and Madison were here today, they would be disgusted at this interview right now. Their conception of American politics was that they were the people who should be ruling the place and you and I should be happy to vote every four years and then go back to our plows.

But the thing is, if we say we don’t agree with American exceptionalism, we’ve got to replace it with something. Cedric Robinson argues for replacing it in part with the story of struggles against injustice. That’s what we get if we look carefully at African-American and Latino experiences in this country. We’ve never been given anything. We’ve had to fight for everything we have. To me that’s a wonderful way of replacing a fairy tale which covers up imperialism and racial capitalism with something much more realistic.

If the US really were the freest nation on Earth in the 1820s and 1830s, even if it were only in the top ten, it would have joined with Mexico in Mexico’s struggle to abolish slavery and Mexico’s struggle against the Spanish empire. Instead, the US did exactly the opposite. The US invaded Mexico and extended slavery into what had been Mexico. That’s just another example of how that myth of American exceptionalism, in devastating ways, really prevents us from actually dealing with these recurring tragedies—Donald J. Trump being just the latest.

CM: I want to get into the way in which the United States tried to export and protect slavery around the world in just a second. But since you touched on Trump as well as the worst aspects of Hamilton, Jefferson, and Madison: to what extent is Donald Trump “making America great again” in that fashion, in the worst aspects of Hamilton, Jefferson, and Madison?

PO: If we put Donald J. Trump back in time at a dinner table with Alexander Hamilton, John Quincy Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Madison, and you said, “Talk about race. You have five minutes. Go,” those gentlemen would have much more in common than they would have differences. They would get along quite well. Their conceptions of who should rule—the white elites—would be in complete harmony.

All of them had differences. We read the Federalist Papers, we talk about the differences between Hamilton, Jefferson, Adams, and others, but on certain issues they are uniform in their approach. John Quincy Adams supported the US invasion of Spanish Florida during the first Seminole war, because he believed we had to defend slavery’s southeastern perimeter. That’s beyond argument.

There are differences, obviously, between John Quincy Adams and Donald J. Trump, but on certain big-ticket items—that is, extending racial capitalism and extending empire—they would march in unison with each other. Those are the types of truths that Cedric Robinson and the other authors in this wonderful volume are trying to get us to understand. But it’s not like we’re saying, “Let’s feel bad about our history.” We’re saying, “Let’s feel good about the histories of struggle.”

When I was in Central America, I didn’t realize at first that there was this amazing liberation theology movement. I realized it towards the end of my time there, and I began learning and studying it. When I got home, I met people who had actually been openly fighting against the US intervention in Central America. I was able to take part in the liberation theology movement and the sanctuary movement. But I had to get out of my ignorance.

My ignorance was thinking that my country was the freest country on Earth, that there might be some problems here and there, but we’ll take care of those in the future; progress will take care of those. But the reality is, we started off on the wrong foot in this country. We’ve got to realize that, own it, and then figure out how we’re going to get out of that mess.

CM: I’m glad you touched on liberation theology. We had the pleasure of interviewing John Dear in the past (a gentleman who luckily avoided that horrible killing of nuns in El Salvador: he had left the building, and then went back and discovered what had happened). He introduced us, at least on this show, to the concepts of liberation theology.

You write, “José María Morelos, leader of the Mexican war of independence, wrote to president James Madison in the summer of 1915 requesting the support of the United States in Mexico’s struggle against Spanish colonialism. Morelos’s program abolished slavery, called for an end to legalized caste oppression of indigenous people, demanded independence from Spain, banned torture, forbade the waging of war on other countries, and promised ‘the education of the poor.’”

As you point out, Morelos was a priest. We know that in the twentieth century, liberation theology by Catholic priests and nuns had a huge impact on independence movements at the time. How much is radical thought that challenges US power—whether it was Mexicans in the nineteenth century, Latin Americans in the twentieth, or African-Americans in the twenty-first—framed within religious (and in particular, Christian) beliefs? Is opposition to US imperialism, whether expressed at home or abroad, driven by Christianity?

PO: I think a good portion of it is. I wouldn’t say all of it, certainly, but when we look at African-American freedom struggles, what Cedric Robinson called the black radical tradition, we find within radical abolitionism in the early nineteenth century, for example, a very strong Christian viewpoint. Radical abolitionists in the early nineteenth century were often using Christian conceptions of social justice to talk about how we need to abolish slavery not only in the US but in Cuba, in Brazil, and other parts of the world. The discourse of Christianity allowed people to communicate across national boundaries.

That’s where it becomes part of the black internationalist tradition. At the same time, though, there are different tendencies within black intellectual thought. If we look at Universal Negro Improvement Association in the 1920s, which is really the largest black mass movement in history, there were wonderful, sometimes competing narratives and strategies. There was a strong Christian tradition within UNIA (Garveyism), but there was also pan-Africanism, there was also Marxism. We can never underestimate the impact of what Cedric Robinson called black Marxism, people like C.L.R. James, W.E.B. DuBois, Sylvia Wynter.

Sometimes these different traditions—whether Christian, atheist, communist, anarchist—are in tension, but oftentimes they work together in really creative ways.

We are born trapped. We’re trapped in this myth that we live in the freest country on the face of the planet, and if we do, then if you protest the freest country on the face of the planet, you can be nothing else but a traitor or a fool, someone to be vilified or marginalized.

CM: You quote John Quincy Adams, who was the leading diplomat at the time of the Mexican independence movement, writing, “The resemblance between this Mexican revolution and ours in the United States is barely superficial. In all their leading characteristics, the wars for US and Mexican independence present a contrast instead of a parallel. Ours was a war of free men for political independence. This, the war in Mexico, is a war of slaves against their masters. It has all the horrors and all the atrocities of a servile war.”

There are those who in the last twenty years of globalization have said that the elite in the US have more of an allegiance and more in common with those within their own class than they do their fellow citizens, that they identify more with the rich of Europe, than they do with their own fellow citizens, that they have more affinity and loyalty to class than country.

Could the same have been said of nineteenth century and eighteenth century American elites? That they had more loyalty to their class than to any fight for democracy and equality like the one the US had just engaged in with the British empire? Is this not that new of a thing?

PO: John Quincy Adams was carrying on direct correspondence with the Spanish Crown, the King of Spain, in the early nineteenth century. He was trying to wrangle Florida away from the Spanish. He’s using those discourses of elite rule and power and hierarchy and race to justify American diplomacy. I think you hit it on the head.

If we look at the American civil war and at the diplomatic efforts between the Confederate States of America and many of the European powers at the time, we see a lot of affinity. It is true that US-based elites, who we call now the 1%, have much more in common (and in their more candid moments they will be quite open with this) with their elite counterparts in Europe and other parts of the world.

This is exactly why the black radical tradition is so important. Cedric Robinson said this quite often: we’re not going to be taught how to liberate ourselves in our school system today—whether it’s private school or public school or the Ivy Leagues or wherever. These stories of struggle are so unusual and so hidden and so forgotten because the system that we live in, racial capitalism, is not going to teach us those tools.

You mentioned liberation theology. I can mention liberation theology to a group of freshmen at the university I teach at, and they would just look at me blankly. They could have had—and they likely have had—pastors in their own communities who took part in the sanctuary movement or in liberation theology. But no one in power is going to help us remember or teach us how to challenge their power. That’s why we have to do it on our own and in concert with each other.

CM: In your opinion, to what degree did the founding fathers stand for the preservation of slavery more than the spread of democracy?

PO: It’s clear that the founding fathers stood for the preservation of slavery even at the cost of destroying the republic. Let’s look at a person like Alexander Hamilton, for example. Hamilton is notorious among African-Americans in the early nineteenth century for his intervention in the early congress after independence demanding Great Britain return the African-Americans who had fled, who had evacuated with the British at the end of the American revolution. Hamilton was so enraged that the British stole what he called “our property,” he really staked his entire reputation on getting those enslaved people back.

I’m kind of digressing here, but the most concise answer to your question would be the American civil war. It was the failures of the founding fathers that brought us to the bloodiest civil war in human history. If you want to call it a success, be my guest. But I come from a military background, and when I read about the carnage that took place during the civil war, I have to place it all right at the feet of the American founding fathers. Staughton Lynd broke this down for us many years ago in a wonderful book called Class Conflict, Slavery, and the American Constitution. Staughton Lynd taught us that if we look carefully at the constitution, it’s designed to enforce property rights and place property rights above human rights—to place property rights above the dignity of the individual.

That’s the US constitution that creates the Fugitive Slave Act. It also creates the Naturalization Act, a corollary to the US constitution which limits naturalization to white people and white people only. These founding father philosophies—and, more importantly, policies—that become enshrined in the constitution get us off on the wrong foot, and get us on the side of imperialism, of racism, of racial capitalism and injustice.

All the traditions that Cedric Robinson talked about are traditions of struggle against these mistakes—though we could use a much stronger word—of the founding fathers. We have to get over Alexander Hamilton, Madison, and Jefferson. We should study them, yes. Study them, learn what they said. But realize they had no love for us. You and I would have no place whatsoever in their conception of what democracy was.

CM: I want to ask you another question about the military. It would seem that US military policy is relatively above criticism among whites compared to among African-Americans. Why is that the case? Numbers would suggest that African-Americans are more likely to have served in the military than whites. And this week there was a story at the New York Times that implied Native Americans are more patriotic than we might think, since proportionally they make up a larger share of the military than other races.

So why would African-Americans be more critical of US military efforts overseas when they are more likely to have served in the military itself?

We’ve got to get over this self-centeredness. It’s such an infantile way of approaching the world. We have to see ourselves as connected to the world and not above it.

PO: In many ways you just answered the question. African-American communities—not just in this generation but across many generations going back to the American revolution—are much more attuned to the actual workings of US empire, because they have been much more likely to serve as soldiers of empire.

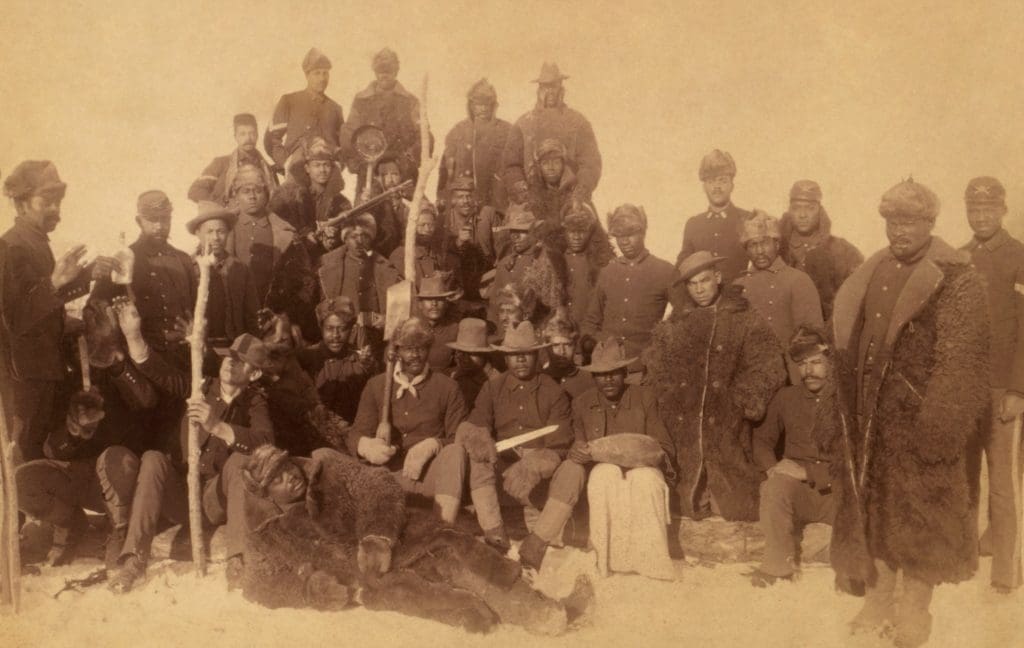

Think about Bob Marley’s wonderful song, “Buffalo Soldier.” When I teach African Diaspora, that’s the first document we look at or listen to. Think about what that song means. It’s a song about young black men who were sent out to serve US empire, putting down Native Americans. This also links up with what you mentioned in terms of the Navajo code-talkers in World War Two. But we can take it even further. Go to the site of the battle of Little Big Horn, the great Lakota coalition defeat of general George Armstrong Custer. If you visit that battlefield, which in many ways represents the apex of Native American victory against the United States, just less than a mile away is a cemetery full of Native Americans who have fought in every war in this country’s history since the time of Little Big Horn.

We find ourselves as soldiers of empire over and over again. When I was sent to Central America in the 1980s, I was fighting people who had the same surname as me. And I had no conception of what I was doing until I began to ask older people: “Where did you serve? What is this all about?” That’s why I think people of color understand much more about empire.

In terms of economics, where else do we go to get a college education? I didn’t have anyone handing me scholarships when I was in high school. We didn’t have college outreach. I grew up in a shipyard town. The generation of African-American veterans of World War Two who went on to become amazing radical scholars didn’t have access to the types of resources that most white upper-middle class people had. Many of us end up in the military for economic reasons.

CM: You write, “Emancipatory internationalism was grounded in social movements, both local and international in scope, that viewed slavery as an aggressively imperial institution that grew by waging war on Native Americans, Mexicans, and others. This was a rejection of the idea later referred to as American exceptionalism, that the United States was uniquely democratic and served as an exemplar to other nations. Just the opposite was true.”

How much do you think any political disconnect between blacks and whites is driven by belief and faith in American exceptionalism?

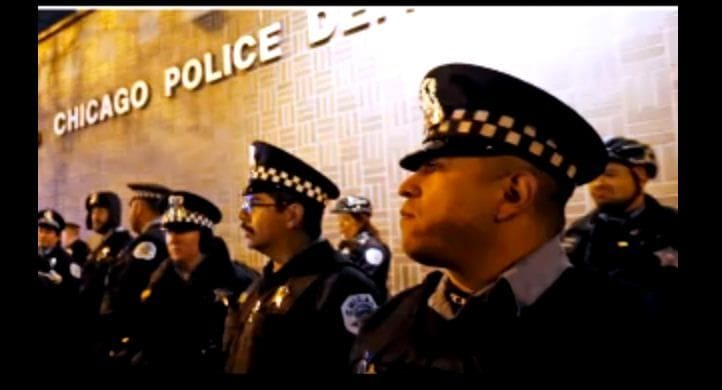

PO: It’s enormous. It articulates itself even in the protests being engaged in by NFL football players. It has manifested itself in the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. Here we have this incredible movement led by a multi-generational African-American freedom struggle tradition, initially initiated by young African-American women—and we see how quickly the broader society vilified Black Lives Matter.

It’s an enormous disconnect. If people were really down with democracy and freedom and justice, they would support Black Lives Matter. They would support the NFL football player protests. They would demand that Colin Kaepernick play professional football. The disconnect is that we are born trapped. We’re trapped in this myth that we live in the freest country on the face of the planet, and if we do, then if you protest the freest country on the face of the planet, you can be nothing else but a traitor or a fool, someone to be vilified or marginalized.

The other side of the coin is, it’s not as if people throughout the world hate Americans. When I first started traveling separately from my army experiences, I would come back to the United States and people would say, “Weren’t you afraid? Aren’t people angry at us about our freedoms?” You’ve got to be kidding me. Other people don’t really care about Americans. They don’t think about us unless we impose ourselves, unless we invade them.

We’ve got to get over this self-centeredness. It’s such an infantile way of approaching the world. We have to see ourselves as connected to the world and not above it. That’s why people like Trump have the power that he has. He’s selling us a false bill of goods. He’s saying we have to understand ourselves as the most powerful nation, the freest nation. If we really believe that, there’s no space for dissent. There’s no space for independent intellectual thought. There’s no space for the dignity of the individual and the right of the individual to disagree with the system.

CM: How far would accepting (or being taught, rather than denying) the history of the US becoming a world power due to slavery, destroying the indigenous, and invading Mexico to support slavery internationally—how far would that go to ending the massive denial the US is in on a daily basis? Is realizing that the people who built America weren’t Rockefeller or Carnegie or Edison or Ford, but slaves—is that what is needed in order to end our denialism?

PO: Cedric Robinson taught us in an amazing way. He was a person of tremendous humility. If we challenge the narrative of American exceptionalism with the same kind of humility, rigorous research, and concise argument that Cedric Robinson modeled for us throughout his entire life, we would go a long way down the road to ending oppression.

However, that’s not quite enough, is it? Cedric also taught us we have to engage in social movements. Think of another part of that black radical tradition: Dr. Martin Luther King talked about education and social action. He said education is wonderful, it’s necessary; learn where you come from, learn your history, learn who you are—but unless you use that to challenge the status quo, then it’s not much good, is it? The reverse is also true. If all you engage in is social action without education, then you’re not really going to do much.

W.E.B. DuBois wrote this wonderful book Black Reconstruction, which is a critique of American imperialism, and I once thought, “Wow, what an amazing, insightful thinker to come up with this idea.” But I realized in my research for this essay that DuBois was a genius rather because he tapped into a black radical tradition, a tradition of social movements, of struggle, and that’s how he ends up with this wonderful analysis of capitalism and American empire.

We have to do both. The learning, changing the textbooks: let’s do it. But we have to go beyond that to engage in a real political struggle, or else we’re only going halfway.

CM: I really appreciate you being on the show with us this week, Paul. Thank you very much.

PO: Thank you so much for having me.