Transcribed from the 5 May 2018 episode of This is Hell! Radio (Chicago) and printed with permission. Edited for space and readability. Listen to the whole interview:

We talk about needing billions of dollars for education, for instance, or for healthcare. Well, that money is easily available if we slash the seven hundred billion dollars of this year’s military budget.

Chuck Mertz: The United States’ permanent war, its militarism and war economy, are not only devastating countries around the world, but are destroying the poor—especially women and people of color—back home in the States. But there may be a way to challenge it. Here to tell us about the war economy’s impact on all of us, and what we can do about it: writer, activist, and analyst on Middle East and UN issues, Phyllis Bennis is a fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies, where she directs the New Internationalism Project. The institute has released a new report entitled “The Souls of Poor Folk: Auditing America fifty years after the Poor People’s Campaign challenged racism, poverty, the war economy/militarism, and our national morality.”

Welcome back to This is Hell!, Phyllis.

Phyllis Bennis: Great to be with you.

CM: The report is an “assessment of the conditions today, and trends of the past fifty years in the United States. In 1967 and 1968 reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., alongside a multiracial coalition of grassroots leaders, religious leaders, and other public figures, began organizing with poor and marginalized communities across racial and geographic divides. Together they aimed to confront the underlying structures that perpetuated misery in their midst. The move towards a Poor People’s Campaign was a challenge to the national morality. It was a movement to expose the injustice of the economic, political, and social systems in the US during that time.”

To what degree did military spending and war play a role in reverend King’s Poor People’s Campaign?

PB: It was a huge factor. The Poor People’s Campaign began its organizing a the end of 1967, and the actual mobilization, what was known as “Resurrection City” in Washington DC, took place the following summer, the summer of 1968, following the assassination of Dr. King—which had of course led to huge uncertainty, grief, mourning, and terror among people who were mobilizing for the Poor People’s Campaign.

And that summer, the summer of 1968—the summer that saw the uprisings of workers and students in France, the uprisings at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, just months after the assassination of Dr. King himself—that summer, thousands of people camped out on the national mall for weeks, in the rain and in the mud, and got virtually no publicity.

There had been a call for this extraordinary gathering of people, concerned not only about poverty and racism, but also about their systemic connection, and at that time it was a question of Vietnam. The war in Vietnam had stripped the ability of the Johnson administration to make good on the claims of the War on Poverty. That was what Johnson had hoped would be his legacy: that there would be new money available for jobs, education, and health care—all the same issues we claim now we don’t have money for, and for the same reason. And it’s because the money was being sucked into payments for the war in Vietnam.

At the time, the US was already spending more than twice as much of its discretionary budget on the military as it was on poverty reduction. Today it’s an even greater gap: almost three times as much. The US today spends fifty-three cents out of every discretionary federal dollar on the military. That’s fifty-three percent of every federal dollar no longer available for jobs, for healthcare, for education, for all of the things that we so desperately need in this country—and that we can afford.

One of the problems that we face is that the result of having such a high proportion of our income going directly to the military means that generations of people in this country, generations of taxpayers, have grown up thinking we really need some austerity, because we just don’t have enough money. We don’t have enough money to pay for what every other developed country in the world has, which is healthcare as a right, made available to everybody regardless of their income. We can’t afford it.

That’s not true. We can afford it. We could have afforded it back in Vietnam. We certainly can afford it now. But we have the same problem of where the money goes. It’s not that we don’t have the money.

Another challenge that we face is the question of what the military actually does, a lot of which we hear in the context of mythology. There was a study as recently as January of this year: it turns out that eighty-seven percent of American voters said that they have either “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the military. No other institution in this country came close. Not congress, not the political parties, certainly not the presidency, not the media, not anything. No other institution had anything close to that level of public support. Somehow people have this idea that “the military” is a thing apart, that it’s something better than everything else in this country.

We don’t think about the people who are dying in Afghanistan, in Libya, in Yemen, in Syria, in Somalia, in all of the places where US troops are deployed, US special forces are carrying out assassinations, US drones are carrying out assassinations, US airstrikes are attacking wedding parties. We simply don’t hear very much about it—partly because of the nature of those wars, and partly because the sorts of people who become journalists in this country tend not to be like the people in the military, who disproportionately come from small towns and rural areas, so journalists grow up not knowing anybody in the military.

All of those factors create this situation that we face now, with this huge percentage of people, eighty-seven percent of people, who think that the military is by far the most credible and important institution in the country, and they have the most confidence in it. That’s a huge challenge for us.

CM: You were mentioning how in the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968, despite being very high profile in Washington DC, was ignored by the media. I know it was a different media climate at the time, but there’s a new Poor People’s Campaign, and I haven’t seen this one in the media either. So to you, what explains why that Poor People’s Campaign in 1968 was ignored? And do you think that the media is going to ignore the new Poor People’s Campaign as well?

PB: I’m not sure I completely agree with you that it’s been ignored by the media. There has been some very good coverage of the Poor People’s Campaign. The day before the campaign was officially launched (which was on November 4 of last year, the same day that the Poor People’s Campaign of fifty years ago was announced by Dr. King), the New York Times had a major piece profiling reverend William Barber, who’s the co-founder and co-chair (along with reverend Liz Theoharis) of the Poor People’s Campaign this time around, and it was very good coverage. Reverend Barber has been on a host of media outlets; he’s spending a lot of time on the road speaking. Reverend Liz, same thing: she’s on the road meeting with people, speaking with people, gathering people.

There are now people in thirty-five states who have come together on statewide campaigns aiming at forty days of civil disobedience, which will be beginning quite soon, with each week having a different theme among these issues that our report deals with and that the original Poor People’s Campaign under the leadership of Dr. King dealt with as well. In those states, the focus will be on mobilizing in the state capitals, and focusing on state policy. And we’re seeing a significant amount of press in the state-level newspapers and media outlets. It’s not all making it to the national press, although some of it is, but we’re seeing a great deal more attention being paid where the target is, which is at the state level.

The militarization of our community hits the hardest in poor communities and communities of color, but it affects everybody. No one is immune from that. We have to recognize that these kinds of effects and consequences of US militarism and the war economy affect everybody.

The idea of the Poor People’s Campaign in 1968 and the idea of the new Poor People’s Campaign now is not simply to highlight the problems that we still face—the problems Dr. King talked about, the evil triplets of systemic racism, materialism, and militarism, with the addition of climate degradation (I think if Dr. King were with us today he would be talking about climate as well)—but looking at two crucial aspects: one is how these four arenas all intersect with one another. How does racism play a major role in militarism in this country (whether within our military systems, in terms of the impact of the military budget or in the choice of where the US forces go to war)? How is poverty connected to environmental injustice? How is the environment connected to militarism? All of these things are connected to each other.

That’s one aspect of how we look at it. The other is, what are the solutions? We talk about needing billions of dollars for education, for instance, or for healthcare. Well, that money is easily available if we slash the seven hundred billion dollars of this year’s military budget. Our military budget dwarfs the next seven countries combined—and those countries are spending huge amounts of money on their own militaries. We’re talking about China, Russia, Saudi Arabia, France, the United Kingdom—these countries are spending a lot of money on the military. And yet we spend more than the next seven countries combined. That’s why we don’t have the money, and that’s the solution.

There is also the issue of cutting the ability of corporations to steal more money and pay their CEOs enormous salaries while their workers get paid nothing. If we combine the ideas of ending the tax cuts for the rich and cutting the military budget, we would have all the money we need for all of these social programs, not only ending poverty, but providing a really world-class education for all our children, providing healthcare for everybody. All of those things would be very easily possible.

Clean water. The fact that we don’t have clean water available here in the wealthiest country in the history of the world is a travesty and a crime. It’s an absolute crime. It’s not only in Flint, as we now know. It’s happening in Detroit; it’s happening in Chicago. There are people who either can’t pay their water bill, or the water that comes out of their tap is not safe to drink. That’s just unacceptable. We could have clean water for everybody in this country. And for only about ten billion dollars a year more, we could have clean water access for everybody in the world. That’s a pittance compared to our military budget.

The military spending simply dwarfs all these other needs, and distorts how we think about the federal budget as a whole.

CM: And as the report states, and as you were saying earlier, “We must break through the notion that systemic racism, poverty, the war economy, militarism, and ecological devastation only hurt a small segment of society.”

So how does systemic racism, poverty, the war economy, militarism—I understand how ecological devastation affects all of us. But how can we convince people that the war economy and militarism actually does affect all of us?

PB: The war economy is one piece of the broad question of militarism. If we look at this issue of the federal budget—this enormous amount of money, fifty-three percent of every discretionary federal dollar, goes directly to the military. First of all, is that keeping us safe? Do people in this country feel safer when we hear that US airstrikes have attacked a wedding party in Yemen, or are responsible, with the Saudi Arabian air force, for killing enormous numbers of people in Yemen? Do we think we’re safer when what is now by far the longest war in this country’s history continues in Afghanistan?

I think we forget sometimes that the war in Vietnam, which we talked about in a way that has shaped a whole generation, lasted ten years. The US role in World War Two was about four years. The war in Afghanistan is almost eighteen years old. The US has been fighting against terrorism for eighteen years, and terrorism is doing just fine. Because you can’t fight terrorism with the military.

So it doesn’t work to make us safer. It engenders more anger, and ultimately more terrorism—that’s one way that it affects everybody in this country. Another has to do with what doesn’t get funded because the money is going to the wrong place. If we want to talk about having top-level schools for every student in this country, something very far away from the reality of what we have now, the immediate answer is there’s just no money for it. Well, of course there’s no money if you put fifty-three cents of every dollar into the military instead. So that affects everybody too.

Also, the question of how Americans are viewed around the world affects everybody. Americans are viewed around the world through the lens of the wars we carry out around the world. This is important when we talk about the cost of war: part of it is what you and I have been talking about just now, the cost to the United States in terms of our federal budget. But we also have to recognize: if it were free, if we could provide in-air refueling to those Saudi bombers that are destroying civilian life in Yemen—would that be OK if it were free? The answer is no, because the cost of war has to be figured to include the cost to the victims of those wars, to the civilians who are dying in such high numbers.

The war in Afghanistan that has been going on now for eighteen years has had successively higher numbers of civilian casualties almost every year. This year, and last year, and the year before, the United Nations—again and again and again—said they were particularly concerned about the growing number of civilians being killed by airstrikes. The Taliban is creating plenty of havoc and is killing plenty of people in Afghanistan, but there’s only one side that has airstrikes, and it’s not the Taliban. It’s us. It’s the US and our allies who are carrying out airstrikes that are killing civilians in huge and rising numbers.

If we could do that for free, do we think that would be OK? I don’t think so. So we have to think about this in an international setting. This is the difference between the militarism component here and the issues around the more immediate questions of the environment and poverty and racism. But they are all connected. And thinking domestically, there’s also something called the 1033 program; basically the Pentagon is allowed to get rid of any surplus military gear by giving it for free to local police departments. A lot of your listeners probably remember the uprising when Michael Brown was killed by police; there was an armored personnel carrier patrolling the streets of the black community in Ferguson, Missouri. That’s not something we should ever see on the streets of this country.

With today’s level of robotics and high-tech warfare, the number of people being hired is way lower than before. It’s not huge factory lines that are producing war materiel. It’s small numbers of very technically trained workers; they are pretty well paid, but there are very few of them. And in the meantime, the profits are enormous.

That’s a big problem that affects everybody. The militarization of our community hits the hardest in poor communities and communities of color, but it affects everybody. No one is immune from that. We have to recognize that these kinds of effects and consequences of US militarism and the war economy affect everybody. We don’t have a draft anymore—it was never an absolute democratic institution that meant every young man had the same chance of being pulled into the military; there were always privileges for rich kids, kids going to college, etcetera, but at least every young man had the same sense of fear when he had to register on his eighteenth birthday. Now, with what we like to call the “all-volunteer” military, the people who go into the military tend to be the poorest. And the people who die in the military, who pay the biggest price, tend to come from the poorest communities as well. What does that say about our country, about how we share sacrifice in this country? That’s something that affects all of us.

CM: The report states, “The United States, since Vietnam, has waged ongoing wars that have little to do with protecting Americans and are much more motivated by profit.” That’s a pretty big claim to make. What would you say to someone who argues that war is the last resort to ensure security, and any money made off of it is merely an unintentional consequence, not a driving factor in why the US went to war?

PB: That’s all true if you believe the political science textbooks and history textbooks that want you to believe that every war we have ever fought was a just war, was a necessary war, and was chosen as a last resort. One of the problems we face is that wars—let’s just look at the recent period, say, post-World War Two—are no longer declared. No war has been declared in this country since World War Two. Presidents have gone to war, and congress has sat back and allowed it to happen, without authority, often based on what we now know are lies (whether it was the so-called Tonkin Gulf Resolution or the claim of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq).

Part of it is that the claims were based on lies. The other part of it is that this is often the first choice, not the last choice. In the moments after the horrific attacks of 9/11, there were already, within moments, discussions in the white house not even about the necessity of going to war against Afghanistan (despite the fact that none of the hijackers were Afghani, they didn’t live in Afghanistan, they lived in Hamburg; they didn’t go to school in Afghanistan, they went to school in Florida; and they didn’t go to flight school in Afghanistan, they went to flight school in Minnesota), but about going to war in Iraq, for reasons that had nothing to do with 9/11. It was a choice.

It was a war of choice. It had to do with oil, it had to do with military bases, it had to do with the expansion of US military power in a strategic part of the world. There were a host of reasons. But none of them had to do with keeping the US safer. And since we know, among other things, that ISIS was created in the context of and as a result of the US occupation of Iraq, we know that that war did not make us safer.

We know that in the US-NATO war against Libya in 2011, ironically it was the diplomat in chief, the secretary of state, who was cheerleading for war. That was a Democrat, Hillary Clinton, who said we needed to go to war, that it was necessary because of humanitarian considerations. It was the head diplomat who said we have no choice, we have to do this. Well, there were lots of choices. And again, it was based on a false claim: that there was going to be an inevitable and imminent massacre of civilians in Benghazi. Many people said at the time that a massacre was indeed possible—there was a terrible situation in Libya—but it was neither imminent nor inevitable. And when the first bombers struck—it was a pair of French bombers that were first in line to drop their bombs—they attacked a column of Libyan military that was leaving the town, because the people of Benghazi had been able to drive them out. They didn’t need French or US or NATO bombers.

But the bombers destroyed the country, led to the overthrow and ultimately the capture and murder by a mob of Qaddafi, and have left Libya what it is today: a completely devastated country overtaken by extremists of all sorts, with three competing governments fighting each other, tremendous levels of violence and the continuing deaths of civilians, and with all the arms caches throughout the country opened up to militant groups that have now spread across the Middle East and the northern, central, and Sahel parts of Africa. This was a result of the supposedly “necessary” decision to go to war.

CM: The report finds that “Washington’s wars of the last fifty years have had little to do with protecting Americans, while the profit motive has increased significantly.” What has led to the profit motive increasing significantly?

PB: There are a number of factors, but one of the big ones has to do with the nature of the wars that we are fighting. In the period after World War Two, when what president Eisenhower first named the “military industrial complex” was first being created and emerging as a major economic force in this country, there was a sense that it could be what it had been before, in the period leading up to and during World War Two: a partial way out of the Great Depression. War production meant jobs. The wars were demanding lots of equipment, and that meant lots of factories, more jobs for more people—including, particularly, a lot of women who got those jobs when more men were being drafted into the military—and the economy was rebounding.

The problem is, that was in a different era where production was different, jobs were different, what was required was different. With today’s level of robotics and high-tech warfare, the number of people being hired is way lower. It’s not huge factory lines that are producing this stuff. It’s small numbers of very technically trained workers; they are pretty well paid, but there are very few of them. And in the meantime, the profits are enormous.

One of the great examples, of course, during the Iraq war, was vice president Cheney, who had spent years as the CEO of Halliburton. Halliburton didn’t manufacture war materiel. It was a war “servicing” company that serviced oil fields and provided contract workers to clean up the bases—to do the things that once upon a time in our country (and every other country around the world) low-ranking soliders did: cooking, cleaning, driving, all those things. Today, in war theaters all around the world, much of that is done not by low-ranking soldiers but by private contractors who are hired either from the local country or from other low-wage countries like Pakistan or India, and paid very badly.

The military is the biggest usurper, if you will, of our collective money, as well as being the greatest creator of greenhouse gases in the entire world. It’s the equivalent of the whole country of Sweden. Just the US military.

Or: they are very highly paid military contractors, paid far more than soldiers for doing the same things under even less scrutiny. There was an incident, a massacre committed in Iraq by four Blackwater guards. They killed seventeen Iraqi civilians. This was the only time that there was even the semblance of a trial, and only because there was such a public outcry about it—those private soldiers are not typically held to the same standards of accountability. That particular case was the only time they were convicted, and in one case sentenced to a long prison term—but within three months the guy was released. So it’s a fraudulent sense of accountability anyway.

The reality is that these companies are making far more money than other similarly-sized companies. If we look, for example, at the first few years of the war in Iraq, the CEOs of these major military companies—the ones that produce weapons, that recruit and train and pay military contractors, all those things—were averaging twenty million dollars a year in income. Then look at the people who are really fighting the wars, who are paying the price for those wars and their privatization. If the average was $19,200,000 a year for the CEOs of these companies, an army private, who I would argue is facing far more risk in those wars, was making just over $29,000. Compare it even with a military general, a general who has been there for more than twenty years: his or her pay would be about $214,000. That’s less than one-tenth of one percent of the almost twenty million dollars a year of these CEOs. The war profiteers are making a killing.

During the period between 2001 and 2004, CEOs generally were doing really well. They were making a ton of money, and they averaged about a seven percent raise during that period. But during that same period, defense CEOs, the CEOs of these military companies, were averaging two hundred percent increases in their already very high salaries. We can see who’s making the money here, and who is paying the price.

One of the famous instances was a guy named David Brooks, who we profile in the report because it was such an egregious example. He was the head of a small company that was producing flak jackets, vests to protect soldiers from IEDs. Very important in the Iraqi war. He was making a ton of money, and when the war broke out he began to get a huge number of new orders, and his profits began to spike—in the one year of 2004, he earned seventy million dollars, and that was an increase of more than thirteen thousand percent over his earlier salary. The irony here was that the bulletproof vests that he was producing didn’t work. Five thousand of them had to be withdrawn because they were fraudulent.

So he was making a fortune and putting the on-the-ground grunt soldiers at risk. It’s just one of those classic things about how this system of privatizing the wars works. There is a much smaller military; you can convince people across the country that the wars are winding down because the number of troops is dropping, without saying that there may be even more private contractors than there are soldiers. It’s misleading, it’s lying to the American people. It’s our community, our young people, who pay the price, and it’s these obscenely wealthy CEOs who are making a killing on these wars.

CM: The report states, “The US department of defense was responsible for emitting seventy-two percent of the US government’s total greenhouse gas emissions in 2016—almost three quarters. The department of defense’s overseas emissions, which are produced during the most destructive operations of the US military, accounted for fifty-six percent of the US government’s total greenhouse emissions. However, these overseas emissions are exempt from the US government’s emissions reduction goals.”

I was going to ask how bad wars are for climate change, but more importantly: can we fight climate change without cutting military spending?

PB: Not sufficiently. We can address all kinds of things. But this is a desperate moment of our planet’s existence, when the very continuation of life on this planet is at stake. Without cutting the military budget to provide more money for paying for all of the existing impacts of climate change that are already unstoppable, and paying for things like normalizing the pricing of wind power, solar power, and hydro power to replace fossil fuels—that’s going to cost some money. We can’t pretend that’s cost-free.

The military is the biggest usurper, if you will, of our collective money, as well as being the greatest creator of greenhouse gases in the entire world. It’s the equivalent of the whole country of Sweden. Just the US military. That tells you something about what our military is doing around the world.

Look at the question of what happens to the water when US military bases are built around the world, and burn-pits that are burning chemicals and plastics filter down into the water table. What happens there? We see the impacts on the overall environments of those areas just as we do on the overall social environment when US bases go up: what happens to women who live in communities near those bases, the rise of rape and sexual assault. All of those things continue to go forward.

This isn’t a hard question, and I hope that many who are listening will not find the answer anything but an inspiration to all of us to take seriously our responsibility to challenge the militarism of our society. If we were able to stop these wars, we would not have the same reliance on fossil fuels that we have today. If we stop relying so much on fossil fuels, there would be more money for developing alternative fuels that will not destroy our planet. And once we have those fuels in place, we will have the potential for infrastructure, for rebuilding not just the bridges and roads but the schools, the hospitals, the universities. Then we can talk about real education for everybody, healthcare for all, the way other countries have it.

It shouldn’t be stunning to us, it shouldn’t be surprising to us when we hear about the healthcare system in France or the education system in Iceland, in all of these places where people are doing better than we are. Women in this country are dying in childbirth at rates higher than any other developed country in the world. Cuba is doing way better than the United States. And black women across the United States are doing the worst of all; they are at greatest risk of dying from childbirth-related conditions. Washington DC has the lowest rank—more women are dying of childbirth-related conditions there than anywhere else in the country. In our capital. That is all unacceptable.

It’s things like the military budget that make that happen. That’s why all of these things are connected. You can’t solve any one of them by themselves. That was what Dr. King understood so well in his Riverside church speech, when he talked about the evil triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism—and we add to that climate degradation. All of these things have to be solved together.

CM: Phyllis, it has been a pleasure having you back on the show. Thank you so much.

PB: Thank you very much.

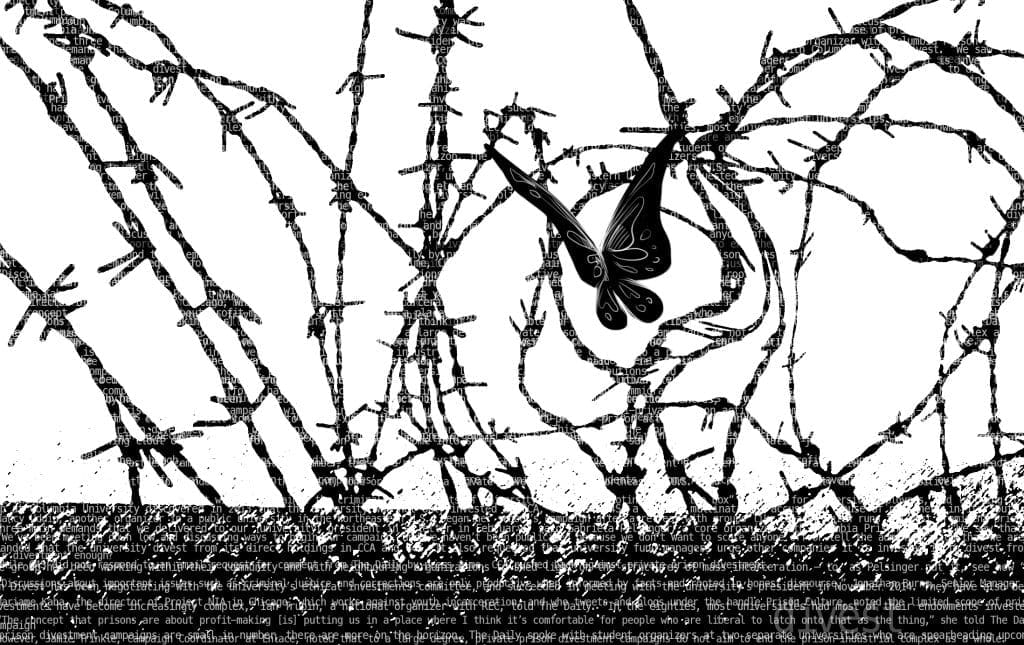

Featured image source: Prison Divestment Movement