AntiNote: On 23 July 2018, Palestinian-American activist Malak Shahin (Students for Justice in Palestine – University of Minnesota) and Syrian-American activist Ramah Kudaimi (US Campaign for Palestinian Rights) spoke to an audience of around fifty people at a Minneapolis bookstore about struggles for justice in Syria and Palestine.

Comparing and contrasting these struggles, they shared a broader discussion of colonialism, imperialism, and capitalism, and emphasized the need for connecting resistance movements from below along precisely these vectors, to build networks of practical solidarity locally and globally.

Full video of the event at the bottom of this post.

Malak Shahin: The hard thing about comparing this stuff is that I don’t always know where people are in their education. How many of you know what Zionism is? How many of you know what the Nakba is, 1948? Okay, a good number of you. I’ll start by talking about both of these things and then skip forward a little bit; I won’t go through all the history.

When we talk about Zionism, we’re talking about modern political Zionism. There are different strains of Zionism that started way back when they were first talking about it. A Jewish person would be better to talk about that, because I don’t know all of the different strains of Zionism. But when we’re talking about Zionism now, it’s modern political Zionism; the founding father is considered to be Theodor Herzl, and he defines Zionism as a colonial idea. He approached Cecil Rhodes, the person who colonized south Africa—he’d recently colonized the territory of the Shona people as Rhodesia. “You are being invited to help make history,” Theodor Herzl said in a letter to Rhodes. “It doesn’t involve Africa, but a piece of Asia Minor; not Englishmen but Jews … How, then, do I happen to turn to you since this is an out-of-the-way matter for you? How indeed? Because it is something colonial.”

In understanding the relationship between Israel and the West in general, it’s important to look at the roots of it. It was a continuation of European colonialism and imperialism in the Middle East and Africa at the time. One of the other places that Zionists thought of making their homeland was Uganda, and also Argentina. But they chose Palestine for pretty obvious reasons.

Herzl looked at Israel as “a state that would constitute for Europe and Palestine part of the wall against Asia and serve as a vanguard of civilization against barbarism.” Let’s think about that when we think about how Israel is portrayed in the news as the “only democracy in the Middle East,” and how Palestinians are portrayed as backwards, with all of these Orientalist and Islamophobic stereotypes that are hammered away on whenever Palestinians are mentioned in mainstream news (which isn’t often unless they want to blame us for terrorism). We’re carrying this long legacy of colonialism, talking about indigenous people as savages and as barbaric. That is really important to understanding the roots of Israel, because it is a violent settler-colonial project. Israel and America have a special relationship partly because they have these shared values—we have to look at the fact that they are both violent, genocidal settler-colonial states, and they continue to be, to this day. They continue to inflict violence all over the world.

When the state of Israel was created officially in 1948, that was when the Nakba happened—nakba means catastrophe in Arabic; this refers to the mass expulsion of Palestinians. Seventy-eight percent of Palestine came under Israeli control. The other twenty-two percent was divided into the West Bank, which was ruled over by Jordan until ’67, and Gaza, which was ruled over by Egypt. Around one million Palestinians became refugees by Zionist forces, and this is not to mention the countless Palestinians who were killed. At least two dozen massacres of Palestinian civilians by Zionist and Israeli forces played a crucial role in the mass flight of Palestinians from their homes.

A lot of the Palestinians who left, left everything behind, because they assumed they would come back when the war was over. A lot of older Palestinians still have the keys to their original houses, because they assumed they would come back. It’s become the symbol of return. The right of return is a really important part of Palestinian advocacy.

These numbers are from the Institute for Middle East Understanding: more than four hundred was the number of Palestinian cities and towns systematically destroyed by Zionist forces and repopulated with Jews between 1948 and 1950. Approximately four million—4,244,776—is the number of acres of Palestinian land expropriated by Israel during and immediately following its creation in 1948. So this was a huge loss for Palestinians, and more than one million Palestinians became refugees. Today there are around seven million Palestinians living in diaspora, and the diaspora includes Palestinians living in refugee camps in Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Iraq; there are Palestinians living in the Gulf, there are Palestinians living in America. We’re literally everywhere, and that’s because of the fact that we’re not allowed to go back home, from the Nakba.

So that’s some background to the conflict—I don’t even like calling it a conflict, because it’s not accurate. But I want to talk more about what’s going on today, and the ways that we can all help and support local activists.

I just graduated, but I was a part of Students for Justice in Palestine at the University of Minnesota. We’ve done two divestment campaigns, both successful. The last one was a referendum in which we asked the university to divest from corporations that are complicit in Israeli violations of Palestinian human rights, corporations that are establishing and maintaining private prisons and immigrant detention centers, and also corporations that violate indigenous sovereignty.

These issues are very much connected. Like I said before, when we look at the roots of Zionism, it’s very much a European colonial construct. For us as activists and as people who are educating people on what Palestine is and what Palestine means and what the Palestinian cause is, it’s very important to be able to connect it to these issues. When you connect them, it drives it home for people. We say that what was happening in Palestine is what was happening in Standing Rock. What was happening in Standing Rock was an issue of indigenous sovereignty, just as much as it was an environmental issue. That’s why we use the terminology of indigenous sovereignty. At first we were considering talking about environmental degradation and linking it to indigenous sovereignty, but the fact of the matter is, people don’t get that. We have to talk about indigenous sovereignty in itself. We have to recognize that we are on stolen land right now. People don’t see that, so we have to make those connections. As indigenous peoples globally, we need to be able to link up and talk about how Israel and America continue to hurt indigenous people globally, the same in Palestine as in North America (Turtle Island).

One thing I recently learned is that Israel armed and trained Guatemalan soldiers when they were committing the genocide in the eighties against the Mayan people. It’s things like that where you learn: that makes sense, but it’s so shitty that people don’t know it. Especially in the way that Israelis like to self-Orientalize themselves and talk about how they’re indigenous to the land—that goes back to the claim that Israel-Palestine is a conflict that has been raging for two thousand years between Muslims and Jews and they can never get along. It’s just a way of legitimizing their claim on the land. Think about how, in the post-9/11 era, in the War on Terrorism, framing Israel-Palestine as a Jews versus Muslims thing always frames the Muslims as the bad guys, always makes Palestinians look like we’re bad, we’re the terrorists. It also ignores the fact that there are Palestinian Jewish people, and there are Palestinian Christians, who are also being persecuted. So we have to be very firm with how we frame things. That was something that we were really trying to do with UMN Divest.

We were looking at the prison-industrial complex and connecting that to Palestine, and that is something that needs to be done more often. Right now, although people are paying a little more attention to what’s happening with immigrant detention centers, people are still asking the wrong things, because they just want people to be detained together instead of being torn apart. But they shouldn’t be being detained at all. These are things that are really difficult to talk about for people, because they don’t see how a country in the Middle East is connected to the prison-industrial complex in America.

By focusing on corporations, which is what we’re doing through the divestment campaign, we’re asking the university to take out its investments in funds that include corporations like G4S. G4S is a British security company, and they’ve been really shitty everywhere. They were at Standing Rock, too; they had the dogs, if you saw the pictures of dogs attacking indigenous water protectors. They were also in Israeli prisons. There were rumors that they were leaving Israel, or they said they were going to pull out (because of BDS pressure—they won’t admit it, but it is). They also do deportations. There was an incident where an immigrant from Nigeria was being deported from England and died while in G4S custody, because G4S uses too much force.

Another company that is involved with private prisons (as well as regular prisons) is Raytheon, the defense contracting company, the world’s largest producer of missiles. They rely on prison labor to produce weapons, and their weapons are also used against prisoners in the LA county jail—these weapons weren’t accepted by the US military for contracts, so they were used by the LA county jail, on prisoners.

Those are the kinds of things that our divestment campaign was looking at, and the kinds of things that BDS targets. As far as violating indigenous sovereignty, that was once again G4S, who were up in Standing Rock. That one can go even broader, because there are so many companies that are violating indigenous sovereignty continually. But we focused on G4S, Raytheon, and Elbit Systems. Elbit Systems built the apartheid wall in Palestine. If you don’t know, there is a really long wall that Israel built around settlements and encroaching on Palestinian land. Israeli settlements are little colonies that they have in the West Bank, and Elbit Systems are the ones who are behind this wall, which is something like eight times as big as the Berlin wall. They are also a company that is behind US-Mexico border security. Once again, there are different connections around how borders are violent colonial spaces, and Elbit Systems is responsible for that; that’s why they were one of our targets.

We also had Boeing. They manufacture aircraft and weapons that supply the Israeli military. Their weapons were used against civilians in Gaza in 2014; they’re likely being used against civilians in Gaza right now. After 2014 they received an $82 million contract to continue supplying bomb guidance systems to the Israeli military.

Those are things that our university is likely invested in through all these different funds, and through our divestment campaign we were asking the university to not be invested in them. The hard thing about that is that these companies are shitty regardless. For me, if G4S pulls out of Israel, it’s not like G4S is suddenly an ethical company. I still don’t want us to be invested in it. It’s really difficult sometimes when we’re running campaigns like this one, because nothing is going to make investing in a weapons corporation okay; just because their products aren’t being used against my people, they’re being used against some people. The fact that we were connecting all these different causes builds the foundation for us to be able to push for more radical demands in the future.

Our first divestment campaign was similar. It was a referendum that everyone could vote on. It was a resolution from student government, but everybody had the ability to say yes or no. BDS, for the past thirteen years (since 2005), has been campaigning to get people of the international community to put pressure on Israel to abide by human rights law. It was called for by Palestinian civil society; hundreds of organizations called for BDS and for people to support it—if you’re for Palestinian self-determination, you have to be for BDS.

It has three main goals: ending Israel’s occupation and colonization of all Arab lands (dismantling the wall, pulling out of the Golan Heights in Syria, pulling out of the West Bank, and pulling out of Gaza, but we’re also talking about ’48 land); recognizing the fundamental right of Arab Palestinian citizens of Israel to full equality; and respecting, protecting, and promoting the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes and properties as stipulated in UN Resolution 194. That’s the right of return—think about the symbol of the key, this is the return of millions of Palestinian refugees who are displaced to this day, who are not allowed to go back, who are still in refugee camps in Lebanon, in Jordan, in the West Bank. The right of return is something that you can’t compromise on. That’s a big part of advocating for Palestine. If you don’t recognize the right of return, you don’t recognize Palestinian self-determination.

BDS stands for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions. Boycotting is more on the individual level; it’s me not buying Sabra hummus because I have morals. Divestment means asking institutions like the University of Minnesota, or churches, to take out investments they may have in corporations such as Raytheon, G4S, etcetera. Sanctions are more on the government level, leading up to the point where, internationally, states are actually holding Israel accountable and placing sanctions against Israel until it abides by international law. Those are the three different levels; boycott and divestment are where we have the most power, but it’s building up to sanctions.

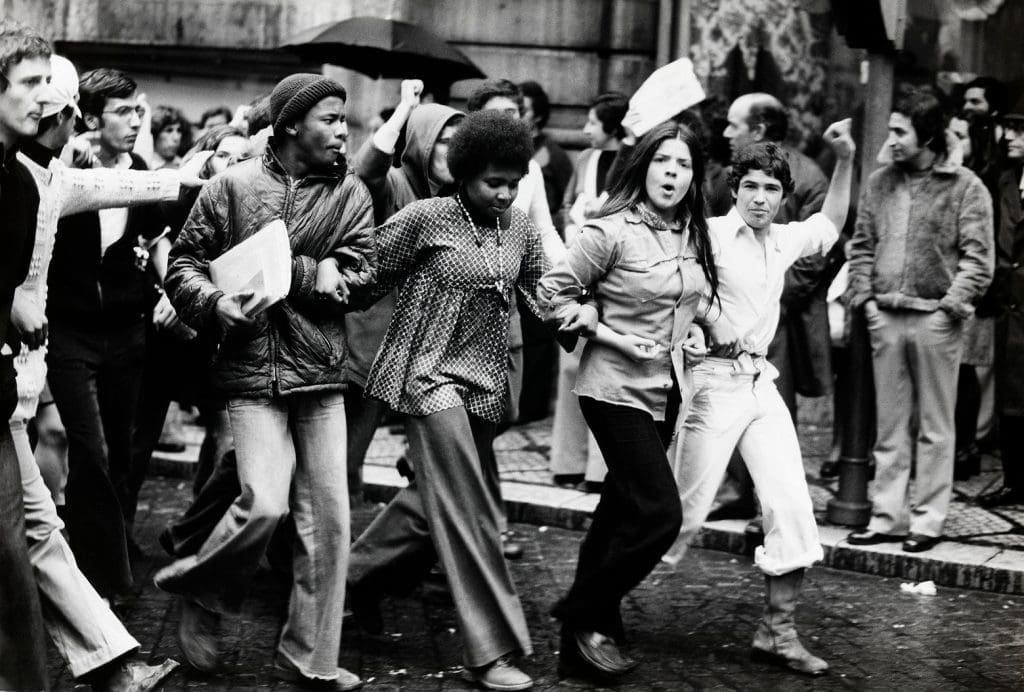

The movement for BDS in South Africa was done through young individuals on college campuses making their universities listen through really radical direct actions. On the University of Minnesota campus, they shut down Board of Regents meetings for eleven years. They would take over Morrill Hall, which is the administration building. There were all these different things that they did; it’s a matter of escalation. By the time universities were starting to divest all over the country, people were becoming very aware of what South Africa was and what South Africa was doing, and why Apartheid was bad. It got to the point where the US congress was able to override Reagan’s veto and pass sanctions against South Africa.

It ended Apartheid, essentially. That’s not to say that black South Africans didn’t have a huge role in that, and it’s not to overstate what role Americans have, but as people in America we are in a unique role to be able to put pressure on the United States and on Israel, because the United States has that special relationship. That’s why BDS is really important, and I think if you don’t support BDS in some way, I don’t think you really support Palestinian self-determination. Like I said, it was hundreds of Palestinian civil society groups that have called for BDS, and that’s been the most effective way for us to make change.

Thinking back to our first divestment campaign at the University of Minnesota, the change in how people talked about Palestine and how people understood what we were talking about, comparing 2016 and 2018—it was huge. We have to keep pushing, make sure we’re educating people, make sure we’re making those connections. That means going back and saying what Zionism is and what Israel is doing and why it’s wrong, and what a Palestinian is—some people don’t know what that is. It’s being able to make those connections and say that Israel was involved in the 1980s with the genocide of Mayans in Guatemala, and they were able to get those contracts by basically selling what they’re doing with their own occupation. I was reading an article on Electronic Intifada about how they basically “palestinianized” the Mayan people—I’m not sure that’s great terminology—by using the same tactics.

That’s what they do. They export their tactics. Again, let’s go back to the prison-industrial complex and how Israel exports its violent tactics to the United States by having these police exchanges. That’s something you can learn more about from Jewish Voice for Peace; they’re doing a campaign called Deadly Exchange, to stop police exchanges from happening.

That’s the biggest thing that I want to drive home: really talking about those connections. The biggest difference between 2016 and 2018 was being able to say that Palestinians are very similar to indigenous people here, because we go through similar struggles. Being able to connect with those people and also connect with people who are supportive of indigenous struggles, they’ll have to realize the cognitive dissonance of being able to support people standing up against Line 3 but not Palestinians who are marching for the right to return or who are protesting Israeli settlements. Pushing that is really important.

Ramah Kudaimi: I want to shout out you students; I’m a BDS organizer, and what students have been able to accomplish is what helps the rest of us do our BDS work, so it’s very inspiring and an honor to sit alongside students and hear about the ins and outs. The opposition is so afraid of student organizing that Sheldon Adelson is pouring in millions of dollars every single year to fight back against students’ BDS activism.

I’m pretty sure you all don’t have anywhere near that amount of money.

MS: Donate to SJP.

RK: Definitely donate to SJP.

Thank you all for coming tonight, and thank you to CISPOS for organizing this event. I’m a Syrian-American activist who does organizing for Palestinian rights as my full-time work, so when I get a chance to talk about freedom and justice for both Palestine and Syria, for Palestinians and Syrians, it’s very special.

Earlier this month, on July 12, forces loyal to the regime of Bashar al-Assad raised their flag over Dera’a, which is the city that was the birthplace of the 2011 Syrian uprising and revolution for justice and dignity. While so much of the news that we hear about Syria these days is unfortunately about violence, about massacres, about airstrikes, today what I really want to focus on is the people. I want to focus on their revolution, so that that part of the story of Syria, the one that is really inspiring and beautiful and heartwarming, doesn’t get lost in all the other horrible things happening.

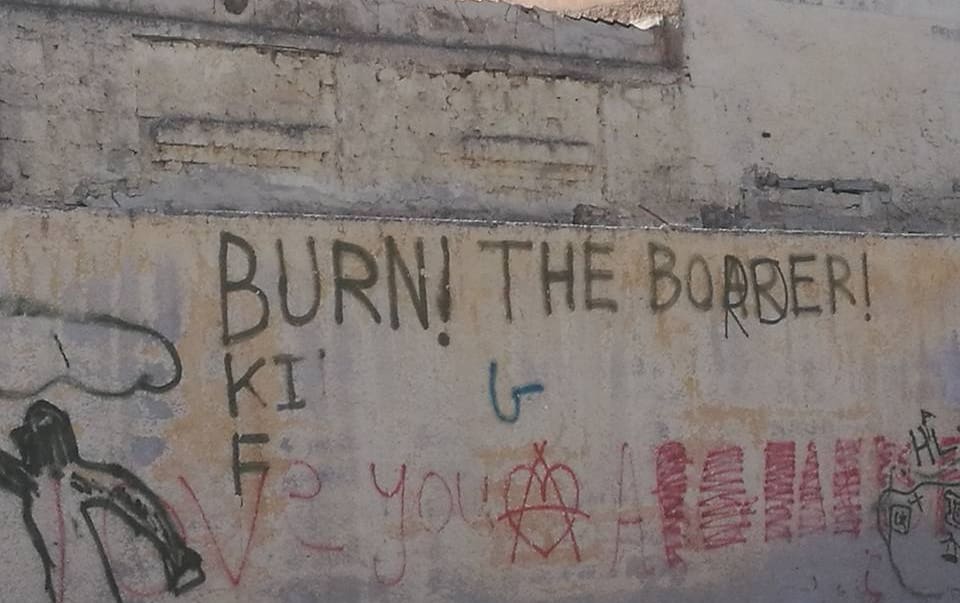

In the most recent history, that story starts in Dera’a. In March of 2011, some youth in Dera’a painted slogans demanding freedom on the walls of their city. They were inspired by what was happening back then all across the region. In December 2010, the people of Tunisia had taken to the streets demanding the fall of their regime after a street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire to protest his mistreatment by police. The protests continued for weeks and ended up forcing then-dictator Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali to flee, after he had been in power for twenty-four years. The call for the fall of regimes spread across the region—to Egypt, to Libya, to Yemen, to Bahrain, and even Iraq, where people had obviously been fighting American military occupation still at that point.

People were inspired, encouraged. They saw videos coming out from each country, and were circulating videos and chants, and people would think, well, if they’re out there in the street there, why can’t we do it here as well? I was in grad school in 2010 and the beginning of 2011 when all of this was happening, and I remember I—and a lot of my friends—would wake up really early in the morning every day for months, following the videos. Protests would start around noontime, so that would be like five o’clock in the morning. I don’t know how anyone got any work done, because that’s all we were doing, just watching videos from Tahrir Square and waiting to see what was going to happen. There was such a feeling of excitement and hope. We were witnessing a breakthrough in a region that had suffered for so long the impacts of British and French colonialism, followed by dictatorship. Its peoples’ needs and dreams were always secondary to the needs and interests of the United States and Israel, and of course the destruction that the US invasion and occupation of Iraq wrought was still having reverberations across the region at that point. People were really forced to think: we have to either accept living under dictatorships, or we’re going to have to accept living under US bombs and US occupation.

Watching the bravery of the millions of people taking to the streets in January and February 2011, many people would turn to me and ask, Is Syria next? And honestly I would say no. I was like, no, there’s no way this would happen in Syria! This was mostly based on how strong a grip I knew the Assad regime had on the country. The current president Bashar al-Assad inherited power after his father Hafez died in 2000. Hafez had ruled the country since 1970, and the Assad regime is frankly one of the most brutal regimes in the region—which is saying a lot. There are people who dream about getting a Nobel Peace Prize; I think these regimes think about getting a Nobel Prize in cruelty and brutality.

I grew up in the United States, but I would go to Syria often. I knew that when I would visit, I shouldn’t be discussing anything political—and no one ever actually explicitly told me that. I think back: did my parents ever sit me down to have that discussion with me? They didn’t. I don’t recall it at all. It’s just something I felt as a kid, to see how fearful people were, seeing how adults around you would just not say anything that would be perceived as critical of the regime.

My parents grew up in Damascus, but my mom’s family is from Hama, where in 1982 Hafez al-Assad killed an estimated forty thousand people to repress efforts to resist his regime. No one ever talked about that massacre in my family, but everyone knew about it and feared that the same would happen again if anyone ever dared rise up. Whereas in Egypt and Tunisia there was some freedom of the press and some space for political organizing (not to whitewash those regimes, which were also brutal—and now in Egypt what we see under Sisi is even scarier than what was under Mubarak unfortunately), in Syria there were only state-owned media outlets and only one political party that you were really allowed to join, the Ba’ath party that was in power.

But in March of 2011, the people of Dera’a proved me wrong. Inspired by what they were seeing in neighboring countries, they painted these freedom slogans on the walls of their city. They were quickly arrested by the mukhabarat (the FBI, if you want to relate it to the US—the intelligence services) and tortured. Immediately, protests erupted demanding their release, as well as addressing other grievances such as high rates of unemployment and other socioeconomic issues that people were facing.

The regime quickly reacted with force, and attempted to repress the protests. By this time, March 2011, we should remember that the people of Egypt had ousted Hosni Mubarak—they had succeeded in making him step down after he had been in power for thirty years. That point was also the beginning of NATO intervention in Libya, where people had risen up against Qaddafi’s brutal regime and NATO had decided to intervene due to his brutal response to protests there. The Assad regime was seeing what was happening, and decided they needed to shut things down and quell any further unrest. Protesters were beaten, and met with tear gas, and within a few weeks the regime was sending tanks to escalate violence against its own people.

What the regime failed to understand from the beginning was these protests that were breaking out in a small city like Dera’a (Dera’a is way in the southwest part of the country near the Jordan border, not a major city) couldn’t remain isolated in Dera’a; in the surrounding villages, people heard about what was happening in Dera’a, saw people killed, and were going out in the streets protesting in solidarity with their fellow people.

The grievances held by people and their demands were things felt across the country. There was an issue of stagnating wages as the cost of living had increased sharply over the last few years. Drought was impacting rural areas. The regime’s neoliberal policies meant the slashing of subsidies, and that obviously meant that everything was becoming more expensive.

And of course the regional context—we can never forget the regional context. Unfortunately, because the region is now in such a dark place, we forget what was actually happening in 2011, the beauty of what was happening. While none of the problems that Syrians were facing were new problems, they were seeing what others in the region were doing and what they were able to accomplish just going out in the streets and making their demands, and that gave them hope that they, too, could do the same. If Hosni Mubarak was able to be forced out of power, why not the Assad regime?

Soon the barrier of fear was broken across the country, as protests spread to major cities like Homs and Hama, more towards the center of the country. Protests spread to the Kurdish parts of the country in the northeast (the Kurds were not considered citizens at that time, and the regime at some point all of the sudden said, “Yeah, you’re all citizens now,” as a way to quell the protests there). There were even protests in the capital, Damascus itself. This probably terrified the regime, that people in such close proximity to them were no longer afraid either.

So the regime decided to crack down on protests, and as the crackdown escalated, it became more vicious and more brutal, specifically in April 2011 when they tortured Hamza al-Khateeb, a thirteen-year-old, and returned his tortured body to his family, with his penis cut off. He had cigarette burns all across his body. People know the case of Emmett Till in this country; that’s what it reminded me of. His body was so mutilated that his own family had trouble recognizing him. That pushed people. If this is how cruelly the regime is going to react, there’s no turning back. We have to keep pushing forward. More people came out in the streets.

So much of the coverage today in Syria is about violence, and portrays Syrians as victims with no agency—I really urge us to go back and really watch. Read the stories and watch the videos of the amazing direct action that took place, the amazing unarmed resistance, the amazing civil disobedience, the creativity of the protesters who went out. There were songs and chants that filled the air during the protests. There were massive sit-ins that happened, workers’ strikes that disrupted business as usual. Cartoons were produced, posters. People were making videos and uploading them to YouTube and various social media sites. Protesters would hand dates and flowers to the regime soldiers, encouraging them: “You can come and join us. We want you to be part of our protest. You can be part of us changing our country.” They created new media outlets—which is, again, a huge thing for a country that had nothing outside of state-controlled media. Now for the first time there were independent media spaces. Local councils started popping up all across the country, where people would come together and discuss protest plans and start imagining what the future of their country would look like.

When I watch videos of protests now, seven years later, it’s really hard to digest how the reality in Syria today is so different from what it could have been back in 2011. Many factors led us to what this reality is today. Today, the Assad regime is still in power. He is consolidating his control over previously liberated areas. The entire international community—for years now—has decided we have to keep Assad in power. Now it’s becoming a reality: he’s staying in power, and everyone is getting into the mode of normalizing that fact.

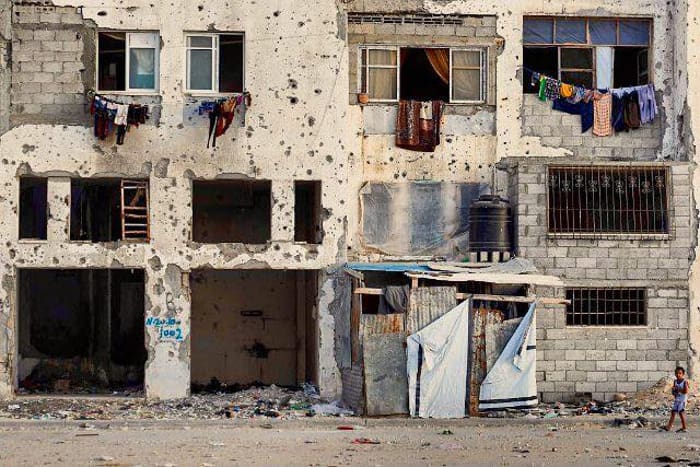

It’s sad. At least five hundred thousand Syrians have been killed—although the UN had this number as the death toll years ago, and they stopped counting. It could easily be double that. Really. There are six million Syrians who are refugees. The idea of Syrians being refugees is a very hard one, because Syria for so long hosted so many of the region’s refugees, whether it was Palestinian refugees or Lebanese refugees or Iraqi refugees—the fact that there are now six million Syrian refugees is a lot to swallow. In addition, there are another six and a half million who are internally displaced, and an unknown number of people—it might be thousands, it might be tens of thousands—in the regime’s torture dungeons and prisons, facing horror there.

Syria had a population of twenty million in 2011. Two thirds of that population have been direct victims of this regime’s war on Syria.

What factors helped get us to these dark days from the beautiful early days of the revolution, when there was so much hope and excitement? There are a couple things I want us to think about. One is going back to 2003 and the US invasion and occupation of Iraq, and the impact that still has to this day, the sectarianism that it set off, the violence. I’m assuming a lot of you are anti-war activists, and understand: what happened in Iraq was horrible. It was a violent occupation that destroyed a society. Obviously Saddam Hussein was a war criminal—his people would have risen up against him eventually just like people rose up elsewhere—but what the United States did was criminal, and there’s obviously been no accountability whatsoever for what happened.

So that’s part of the picture. Another part of the picture is NATO’s intervention in Libya in 2011. Again, that signaled to Assad—and signaled to Assad’s backers, Iran and Russia, that they would need to double down their support. It showed that there might be interest among NATO countries in helping Syrian revolutionaries oust Assad, and that made them very fearful because then they would lose any control that they had in the region.

We’re back to this now; I don’t know if people saw Trump’s tweet about Iran last night. But since the nineties, the United States and Israel have been pushing for war on Iran—and not because they care about the Iranian people. This is about their own “security.” And for Israel, this is a deflection from Palestine. Then there’s the role that Israel played in convincing the US to invade Iraq, with the idea that Iran was next; there are the lies around Iranian nuclear weapons. Bibi Netanyahu, since the nineties, has been claiming that Iran is within two to three years of having a nuclear weapon. It’s a lie, because it’s about deflecting from Palestine and the issue of Palestinian rights.

Slowly, Syria became a global battleground, a battleground of geopolitics. There were forces who wanted to make sure the regime stays in power: that includes Iran, that includes Russia, and that includes Hezbollah (and then there are various militias that Iran would bring into the country; for example, Iran would force Afghan refugees who were living in Iran to go fight in Syria). Then there were the so-called friends of the revolution. So-called friends. No one has the interests of the Syrian people in mind other than the Syrian people themselves. But these “friends” included the United States as well as the various Gulf powers, from Saudi Arabia to Qatar to the UAE, who were always promising a lot more support to the revolution than they actually ever gave—or than they ever really wanted to give—and they were very clear that any support they gave was contingent on their own interests, making sure they controlled whatever the outcome would be.

And then there’s the War on Terror, the War on Terror that George W. Bush launched after 9/11; the first part of that was the invasion and continuing occupation of Afghanistan (we’re now in 2018; seventeen years later the US is still occupying Afghanistan). The War on Terror has become a global war on terror, where any power that wants to can just claim they are fighting terrorism, and everyone says, “Okay! That makes sense.” That’s what Syria has become. It’s become an issue of the War on Terror. The US is “fighting ISIS,” Russia is “fighting ISIS,” Turkey is “fighting Kurdish terrorists.” Everyone is out to ensure that the people they don’t like are labeled as terrorists and that they are able to kill those people as they please.

Then, frankly, there has been international community incompetence. The UN has been unable to do much, because of the veto power of Russia and China; similar to what the US has done with Israel for decades, Russia has protected the Assad regime. And then there is the lack of solidarity beyond the institutions. I work on Palestine, so I don’t have much trust in the UN. But as to what Malak described in terms of BDS and the ability for people worldwide to take action for Palestinian rights: unfortunately we’ve seen a lack of that solidarity in regard to Syria. To be very fair, of course, it took decades to build a solidarity movement in support of Palestinians, so it’s not like it’s going to happen automatically in Syria.

What’s been frustrating about Syria is how people who should get it, don’t get it. The regime claims that it is an anti-imperialist regime, even though this is a pure lie. The regime is one that, for example, was okay with the US invasion of Iraq. It’s a regime that worked with the CIA in its torture and rendition program. They would accept people from the United States that the US government wanted to torture, and they would torture them on behalf of the US government. The CIA was very clear: if you really wanted someone to be tortured, that’s where you would send them. You would send them to Syria. Some people may have followed the case of Syrian-Canadian Maher Arar, who was wrongly renditioned. The US government thought he was a suspected “terrorist,” sent him to Syria, and he was tortured. Finally they were like, “Oops! We made a mistake,” and our court system didn’t even let him sue the US government. He got some justice from the Canadian government—from the US government, none at all.

There are also the neoliberal policies that I mentioned. The rich got richer and the poor got poorer, because they were slashing subsidies and everything was being privatized. How can you be an anti-imperialist when you’re feeding into neoliberal capitalism? That’s the front we’re fighting on. A lot of that has confused people to the point where they actively believe propaganda from the regime, where this is all a Zionist-CIA-Mossad-Google-Turkey-Gulf conspiracy (again, as if the Syrian people have no agency). People literally believe that Syria was a socialist country. “There was free education and free health care!” That’s not socialism, first of all, but the quality of it is another story. It doesn’t matter if you have free health care and free education—and it’s crappy healthcare and crappy education—if you have no political rights whatsoever. There is this idea that if you have some economic rights you can do away with political rights.

Even for people who don’t go to that extreme, who don’t actually believe in the Assad project or the Assad propaganda, there is still an inability to speak out against it, or people say they just don’t know—again, this is because of the effectiveness of the propaganda from the regime, very much supported by Russia. People are paralyzed; they say, “Well, I don’t know what to believe.” For activists who are leftists, who are antiwar, who are used to a binary of imperialism and anti-imperialism (and that binary is the US and everyone else), we seem to have lost our critical thinking skills. It’s like, if you’re against the US, you’re my friend and I won’t speak up against you. Or, I have a duty to speak up about US war crimes and I don’t need to speak up about anyone else. It’s not a very internationalist stance, or how we should be thinking about things. We shouldn’t be limiting our solidarity based on borders.

As a leftist, I think internationalism is a number one priority for all of us. Wherever people are who are oppressed, we shouldn’t be on the side of the oppressor, no matter who’s doing the oppressing.

I’m going to end with a couple more points specifically around Palestine and Syria, and why these two need to be talked about together. It’s very disconcerting to me that we don’t actually talk more about them together; there’s Palestinian activism happening and the whole Palestinian solidarity movement, and then there are folks interested in Syria and the whole Syrian solidarity movement, and rarely do they really interact, even though the countries are right next to each other.

Malak was talking about Zionism and about the impact of Zionism on Palestinians: obviously Palestinians are the first and foremost victims of Zionism—but Zionism’s impact goes beyond that. It goes against the region. It goes against Muslims worldwide: the role Zionism and Zionist institutions play in propagating Islamophobia is huge. As Malak was describing, part of the appeal of Israel is to continue the idea that We Are Like You. “Those are the barbarians, those are the savages, but we are like Europe; we are like the United States; we are civilized.” To continue that myth, they have to continue to push Islamophobic tropes. Again, it’s not just within the Israel lobby and among Zionists; reporters understand that history and they know that they have an in with the United States to continue to do that.

We have to talk about the impact of Zionism beyond just the region itself. Syria has occupied territory: the Golan Heights have been occupied by Israel since 1967. And it’s been the “quietest border” for the Israelis. The Israelis will admit that. The idea that Assad is anti-Zionist and he’s anti-Israel and that’s why Israel wants him gone is a joke. He’s protected Israel. When the regime first sent its tanks to Dera’a, people were mocking him: “The Golan is that way! Why are you sending tanks here? You talk about freeing our land, go actually free it! It’s been occupied since 1967!”

So that’s one point I’ll make. The other point I’ll make is in terms of the specific role of Palestinians in Syria and Palestinian refugees in Syria. There are at least 150,000 Palestinian refugees in Syria, all across the country, but most in Yarmouk refugee camp, which is in the suburbs of Damascus and which for many Palestinians was considered the hub of Palestinian diaspora. Palestinian refugees get different rights in different countries; they’re treated the worst in Lebanon; they’re treated the best in Jordan; Syria was in between. They had a few more rights than they had in Lebanon, but they weren’t granted citizenship like they were in Jordan, for example.

The regime likes to talk a lot about how it’s at the forefront of protecting Palestinian rights, and yet—again—this is a farce. This was a farce long before 2011 and the revolution. There was a massacre in 1976 in a refugee camp as part of the Lebanese “war.” A lot of people may know about the Sabra and Shatila massacre that happened in 1982, when Israel allowed extremist phalangist forces to go into Sabra and Shatila Palestinian refugee camps and just massacre people. Well, six years earlier there had been a massacre at another Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon called Tel al-Zaatar, and that was a massacre that was facilitated by the Hafez al-Assad regime.

Also, there is a branch of the intelligence forces in Syria called the Palestine Branch, and it is notorious for being the one that engaged in the worst forms of torture. Imagine thinking that you’re honoring Palestine by naming the branch of intelligence that engaged in the worst forms of torture after it.

When the revolution started, Palestinian-Syrian refugees were put in a bind. What do you do? They don’t have anywhere else to go. They’re not allowed to go back to their homeland, as Malak was saying. They are denied their right of return, so it’s very hard. Eventually Palestinian-Syrian refugees—it started early on, and then more and more—rose up. People in Yarmouk rose up. People in different camps rose up and were supporting Syrians in their revolution. It was very powerful and very beautiful.

In May of 2011, the first Nakba Day protests that took place after the revolutions had started, Palestinian refugees in both Lebanon and Syria decided, “You know what? We’re just going to walk home.” So the Great Return March that we’re seeing in Gaza now, of people attempting to do just that—there was a version of that which happened in 2011, of refugees in Lebanon and Syria. They started walking, and they were shot at. And it wasn’t the Israelis shooting at them, it was the Syrian regime and the Lebanese regime.

Again, the idea that Assad is somehow supportive of Palestinians is ridiculous. There have been about three thousand Palestinians killed, many of them under torture. Yarmouk camp has been decimated. The regime first bombed Yarmouk in December of 2012, and then slowly completely put it under siege for years. Again, we know Gaza has been under siege for eleven-plus years. There is another Palestinian population that has been under siege for years, but it’s not by Israel, it’s by the Syrian regime, which claims to be a supporter of the Palestinian people.

Yarmouk had a population of about 150,000. It’s down to maybe ten thousand at this point. These are people who were forced to flee: refugees who now twice have been made refugees. When we talk about Palestine, and how right of return is such a big part of the movement: these are people for whom it is even harder to realize their right of return, because now they are scattered in Europe or in other parts of the country, and facing even worse challenges. Because while Syrian refugees’ services are provided by UNHCR, the UN High Commission for Refugees, Palestinian refugees come under UNRWA, a completely different thing. UNRWA for years as been a way for Israel to get rid of the idea of a Palestinian refugee once and for all. They’ve been pushing to defund UNRWA, and to cut services. For Trump, that’s his biggest thing too: he recently cut a lot of money to UNRWA services. They want to get rid of the idea that there is such thing as a Palestinian refugee.

It’s very important, when we’re talking about Palestine and we’re talking about Syria, to make these connections. There is no way there is going to be freedom for Syria while the Zionist regime exists in the form it does. And there is not going to be liberation of Palestine while not only the Syrian regime but really all the Arab regimes are dirty players working to support each other. We are in a world where all of these regimes are coming together. We’re seeing the rise of fascism across Europe. It’s not coincidence that Netanyahu is best friends with Trump, and it’s not coincidence that Putin goes and talks to Iran and Turkey about Syria—as they are all occupiers of Syria—and then he goes and talks about Syria with Trump and with Israel, who are also occupiers of Syria.

People talk a lot about Syrian sovereignty, and how that’s why we need to support Assad, because he’s protecting Syrian sovereignty. It’s because of Assad that there are now six different countries who are occupying Syria, and Syria as a nation-state really does not exist anymore.

One last thing, because we are in a very dark time. Terry asked me yesterday what I think is going to happen in Syria, and it was hard for me to think of anything positive. But I do want to urge people: we need to think about the refugees, refugees from both Palestine and Syria. Refugee rights need to be essential, and we need to figure out ways to protect their rights and to continue helping them survive until it’s time for them to go home. Helping them survive does not mean us having a savior complex. We’re not going to “save” these people. But what are the basic needs that these people have so they can survive and do their own self-organizing? They don’t need us to teach them how to liberate themselves. They know what they need to liberate themselves. They know what liberation for them looks like. But they are under such extreme conditions—how can we lessen those conditions so that they have the space and the ability to organize and think about what their future is more intentionally.

Another thing I want to stress: people, you need to talk with your friends about Syria. You need to talk to your friends about Assad. Read. It’s ridiculous how little people know. And especially with Syria, in terms of the revolution: watch those videos. Remind people to watch those videos. Because again, we only think of violence. Violence is not inspiring. Seeing death and destruction on your television does not inspire people. What inspires people is seeing this is what Syrians did in 2011. They were able to liberate towns? They were able to create committees and talk about their future? Wow. Let’s think about that.

Let’s learn about this. Let’s connect with Syrian refugees, if there are refugees in your community; let’s support educational efforts. If you are an educator, have your students read a book about Syria. If you’re an artist, do an exhibit on Syrian art. If you’re a musician—there is so much amazing Syrian music and art coming out. Make it part of your life. If you’re a doctor, go on a medical humanitarian aid delegation. A lot of times people are like, “Well, I have so much on my mind.” Find ways to connect it to your day-to-day life. That’s the least we can do.

So many times, Syrians think no one cares about us. But if people in their communities are coming together to talk about Syria and letting people know this is happening, it makes a whole lot of difference. There are people interested in what we continue to go through.

Transcribed by Antidote. Edited for space and readability.

This event was hosted by CISPOS – Committee in Solidarity with the People of Syria, Students for Justice in Palestine – University of Minnesota, Mizna, Living Table United Church of Christ, and the Twin Cities Industrial Workers of the World and its General Defense Committee local 14.