AntiNote: Throughout the revolution and genocidal counterrevolutions in Syria, and amid all the fraught intricacies and conflicts within the rebellion against the tyranny of Assadism and the myriad nihilistic forces it spawned, Abdel Basset al-Sarout was frequently elevated as a central emblematic figure. His life and struggle do indeed encapsulate the complexity and damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t dimensions of the uprising and war there.

Under the grim circumstances of his early death defending Idlib last week (he was just 27), we feel compelled to present him in his own words, with all his inner contradictions on display. This interview first appeared in English on the irreplaceable EA Worldview website in 2016; we reproduce it here with their kind permission. It was translated by @malcolmite from a video interview conducted by a fellow opposition activist, Khaled Abu Saleh.

The full conversation (in Arabic) will be embedded at the end of the post. Even if you don’t speak Arabic, it is worth watching for Sarout’s singing alone. May he rest in power.

The Hope and Tragedy of an Uprising

Interview with Abdel Basset al-Sarout

Posted by Scott Lucas on EA Worldview

8 May 2016 (original post)

Note from EA Worldview: Abdel Basset al-Sarout is one of the leading figures in the uprising against the Assad regime in Syria’s third-largest city, Homs. A former member of Syria’s under-20 football team, he was prominent in protests, singing and leading chants.

As protesters began defending themselves against attacks by the regime’s security forces, Sarout took up arms and organized a brigade of local men. His uncle and all four brothers were killed, and Sarout himself survived multiple assassination attempts.

He persisted with resistance, notably during the protracted siege of Homs. When almost all of the city fell to the regime, he continued the fight by organizing another brigade to fight in central Syria.

Sarout has drawn controversy for his activity, notably when he was accused by the jihadists of Jabhat al-Nusra of fighting for the Islamic State.

In April 2016, he gave an hour-long interview to talk about the Homs uprising, his decision to fight, and the battle to clear his name.

* * *

I: The Rising in Homs

Khaled Abu Saleh: Tell us about the beginning of the revolution.

Abdel Basset al-Sarout: I cannot describe the beginnings of this revolution with mere words or actions. It was the most beautiful at its inception, and the beginning was much more difficult than what we are witnessing today. I was at the grassroots of the revolution, and I went out to support the people.

KS: Tell me about your first protest where you proceeded to sing.

AS: My first protest was at the clock tower in Homs. I went out with the protesters in honor of the martyred, and there were Assad regime snipers posted around the area. So I led the chant: “Listen, listen oh sniper, this is my neck and this is my head!”

KS: You also used to host other celebrities at your demonstrations such as the starlet Fadwa Suleiman. Could you tell us about this experience?

AS: Firstly, we hosted many brilliant celebrities from all sects; Homs was gaining the reputation as the capital of the revolution and spirit of the revolution. We represented the most beautiful demonstrations of the people of this country, among them Fadwa Suleiman and other actors, and many from the area of Salmaniyah. We all had the same objective: the fall of this regime and calling for freedom. We were all united in speaking up against this tyrannical regime and all its oppression.

KS: In the first year of the revolution, you and your group used to move from one place to the next, from Deir Baalba to Bayada to Khalidiyeh to Bab Amr. How did you manage to move around (since all residents of Homs were well aware that regime checkpoints were widely dispersed), and how did the residents welcome you?

AS: Of course just conjuring up the memories of those days brings tears, and also happiness. These situations were the most precarious. There would be two checkpoints separated by only four hundred meters, and we would have to cross between them on foot. At times we were subjected to live fire. When we reached Khalidiyeh, we would realize that the residents were actually waiting for our arrival, and all the areas were in solidarity with each other.

KS: The regime offered a cash reward for leads on your whereabouts. Even now, very recently, the regime has put a high price on your head. Could you tell me why you think the regime wants to capture or kill you, and who are the people who have tried?

AS: I don’t know how to answer this question for you. Should I answer it as an individual who has been oppressed, or should I answer it with the spirit of the revolution, or should I answer it with all simplicity, or from my own experience? The subject of this question is very disconcerting.

Oh people, we are the family of the revolution, we are the ones that went out and we were the ones that the regime were in pursuit of. We were the ones who the regime was paying large sums of money for people to kill us, meaning we were more powerful than the weapon. This is undisputed. Yes, the weapon has a role, and you know very well that taking up arms was forced upon us.

However, you know when they start pursuing you and offering money for your murder, this means that your voice is very great. All these voices had the regime quaking.

KS: How did you find the response of the regime to the demonstrations? Was it proportionate? Was it reasonable?

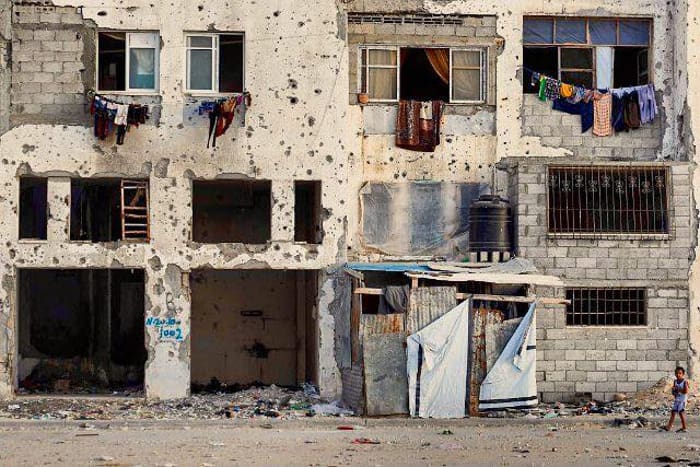

AS: The soil of Homs, the blood of Homs, and destruction of Homs, and the martyrs—the picture is clear, it was a brutal response. You would think we were producing chemical weapons in Homs to warrant such a response from the regime with its entire arsenal. In fact—with the exception of airstrikes—we were the first ones to experience it all. Even chemical weapons: we were the first casualties of such attacks, even before Ghouta [near Damascus in August 2013]. Deir Baalba and Bayada were the first to be subjected to it.

KS: In the beginning of the revolution, was the regime more frightened of demonstrations or of the Free Syrian Army?

AS: They were both interdependent. The protests were breaking the regime’s back; they were the earthquakes below the throne of this regime and sent a clear message for all the people. However, after the attacks on protesters, the demonstrations and the Free Syrian Army would complete each other.

* * *

II: The Battle Against the Regime

KS: Why did you—already known for being a pioneer in the revolution—take up arms?

AS: We made the decision to take up arms because initially we went out with olive branches and bared our chests. We never had any intention of taking up arms. We showed the whole world the full picture of what was happening, once they saw us demonstrating with no bigotry or sectarianism—and on top of that being killed. We had no choice anymore but to defend ourselves, to defend our land and our honor. The matter of jihad in self-defense is nothing to be ashamed of. This is a commandment from god, to defend oneself.

This constant pressure on us forced us to take up arms, but it was the last thing we wanted to do. You keep hearing every day about a protester being killed, day after day, eventually you realize that you must defend yourself.

KS: How did you form your brigade? Who does it consist of?

AS: Martyrs of Bayada Brigade were composed of the same exact people that used to help me organize the protests, who wrote the placards, who would play on the drums, who cleaned before and after the protests. We were all the very same circle of people. In later stages, I would simultaneously fight and then put down my weapon and join the protests. My group would organize and unite the people, and make announcements.

KS: You were fighting on the most dangerous front [in Homs — Ta’minat]. Were you not afraid because of your lack of experience in warfare?

AS: See, we gained all our military experience from this front. Our main military successes came from this front, but after we lost Khalidiyeh, after losing Ta’minat, and after losing Bayada and Deir Baalba from intense airstrikes with little military experience, this was a big problem.

* * *

III: The Siege of Homs

KS: In the beginning of the siege on Homs, you withdrew to the direction of Rif, so that you could meet up with other fighters to break the siege. Tell us about that.

AS: When I left the siege, I left to gather food for the brigade. I decided to organize a new brigade to break the siege from the outside. It was rigorous work. I was exhausted, and even injured twice in the battle to break the siege. The battle of Deir Baalba was the most successful—it resulted in breaking the siege.

In the battle of Deir Baalba, we had up to 120 men and captured it immediately. We did not expect it to be so easy but god gave us success. We would then simultaneously advance to Bayada, both the ones under the siege and the ones outside the siege. The ones on the inside were extremely successful, and there was only a short distance remaining between us and them—that’s when the Assad regime hit them with chemical weapons.

The regime also hit us who were in Deir Baalba with chemical weapons. That was the very first time chemical weapons were used. We had cases of suffocation. Many people died, and that’s why the breaking of the siege eventually failed. If the regime didn’t realize we were about to break the siege, they would never have used chemical weapons.

KS: After you couldn’t break the siege, you decided to re-enter the besieged area. Why did you go back into the siege?

AS: Those who leave their home and become strangers find that being a foreigner is much harder. You hear the Syrian refugees sometimes say, “I wish I could go back to my home, even if I had to die.” I decided that I would return, in solidarity with those under siege—that we would starve and even die with each other, and if god granted us liberation then we would all be liberated together. At least we could rest assured that we did all we could before god, but even then we have so many shortcomings.

KS: A day later, your brother was martyred.

AS: Yes. I was shot in the stomach, and my brother Mohammed was martyred. May god accept him.

KS: How did you feel inside the siege after two years, resorting to eating leaves? Did you feel abandoned? Did you feel no one was trying to break you out? What kinds of thoughts were going through you mind?

AS: We went through stages—see, the moment we went back into the besieged area, that’s when the real starvation started. Before, you could get a hold of some bulgur wheat or regular wheat. After a month, there was no more food. We were reduced to eating grass, chili flakes, and pomegranate syrup, and soup consisting of water and spices and grass. It was difficult, but god gave us the strength to withstand.

As for news coming from beyond the siege, we stopped believing anything we were hearing. We only had our hopes with god.

What made it easier was that the siege was full of blessings. Every hardship would bring us closer to god, to be rewarded. In every step, there was a reward with god. Imagine if you had died, in defense of your rights, defense of your land and religion, in such a throttling siege. It reminds you of the days of the companions of the prophet—of course we will never reach their status. You feel as though god has chosen you, and this alone would be soothing to your heart.

KS: Tell me about the flour mill where around 64 young men were killed attempting to bring back flour to make bread for the children. A large number of your men were also killed, including two of your own brothers.

AS: In all honesty, the conditions of the siege and this incident—if all the historians of the world were to write about it, it will stand as legendary in its own right. It is the epitome of valor. Even the definition of valor would fall short, and I am not just talking about my brigade. In this battle, we were just a branch in many branches where we all worked together under the siege. Again, by god, I am not talking specifically about my brigade or my two brothers who were killed.

A woman would go out into the street and cry, “Who will provide food for my children?” This was the reason for this operation, and we made the conscious decision when heading to the flour mill that either we will all die or we will succeed in bringing back flour. We partly succeeded, but the operation ended in failure and our reward is with god.

KS: Could you tell me what you felt as you were being escorted out of Homs in buses—to your right was the mosque of Khalid Ibn Walid—after such a long siege and the endured hardship and martyrdom of the finest youth of Homs?

AS: [Breaking into song] “Our Homs, Our Homs, Our Homs, I swear I never wanted to leave you, you are within us. Oh Master Khalid, Oh son of Walid, may god never allow our efforts to be wasted. The soil of Homs is like the soil of al-Quds. We will return by the promise of our Lord, we will wipe your tears dear mother.”

KS: After you were transported to northern Homs in May 2014, you were welcomed into the people’s homes; could you explain to me what you were planning to do after this?

AS: Of course we had already planned the next stage before we were evacuated. We had decided to organize under one movement called “Fallaq Homs” and because of what we experienced during the siege, our immediate goal was to break the siege on the people of al-Wa’er [the last remaining opposition area of Homs]. There were more than 150,000 besieged civilians, women and children there. It was obligatory on us to think of these people. It would be a crime for this revolution if we did not work to break this siege.

* * *

IV: The Allegations About ISIS

KS: Soon after you formed Fallaq Homs, you left it. Shortly after that, rumors started to circulate that you gave allegiance to the “dawlah” [Islamic State]. What are the origins of these rumors, and what are they grounded on?

AS: There is no smoke without fire. If there were no basis to these rumors no one would even bring up such an accusation. So I can confirm it does have a basis.

Seven months after I left Fallaq Homs, I was in contact with a man called Abu Dawud from eastern Homs, from the Ahlul Sunnah wal-Jama’a group. He had left this group and was searching for fighters to form a new splinter group that would eventually give allegiance to ISIS. I was one of those people looking for work. I was frustrated by seven months of no progress with my previous group trying to break the siege.

KS: So what did you do with Abu Dawud?

AS: We gathered some groups, including mine. They asked us: “When ISIS reaches this area, will you be prepared to give allegiance?” In all honesty, I was one of those willing to give allegiance because I wanted to work. So I told Abu Dawud, and he automatically took it as allegiance. However it later became clear that it wasn’t a valid way of giving allegiance, and it was nullified.

KS: So was he actually an agent of ISIS?

AS: No, Abu Dawud was just like us. He had no affiliation. This was his own hypothetical project that ISIS played no part in or had any knowledge of.

KS: So he was just a regular person who thought of starting a group that would give allegiance?

AS: Exactly, it was just an idea. He was just seeing how many people would be willing to give allegiance, and after he got the numbers on that basis, he would then talk to ISIS and ask them if we could give allegiance. So we were never actually affiliated to ISIS or even gave them allegiance. Even my own pledge of allegiance to Abu Dawud was invalid because he had no authority from ISIS.

From this basis, the rumor started that “Basset pledged allegiance to ISIS.”

KS: OK, what provoked someone like you to contemplate even joining ISIS?

AS: Many people were provoked to consider joining, not just me. When you as a brigade get out of a siege, and as fighters start getting offered backing, you have no other choice but to work with what you have. You see brigades being starved of supplies for such a long time, and witness no political headway. You have every right to look for a way elsewhere. As for the Dawlah [ISIS], they were already in the Rif by the time I left the siege.

By the time I left the siege, there were also [Jabhat al-] Nusra, Ahrar [al-Sham], and many other battalions. Back then they weren’t fighting each other.

KS: In the beginning of April [2015], ISIS dispatched a group of its Sharia legislators—around eight individuals—to the Rif of Homs. Of course at this point there had been no presence for ISIS in this specific area yet. But they sent eight legislators to receive the pledge of allegiance to ISIS, and even opened training camps. Did you ever meet any of these legislators? Has there been any communication between you?

AS: In that period, during gatherings there were people that knew each another from every group. Some mistakes were made by some groups that were an anathema to the religion and the revolution, so I decided to withdraw. Mistakes were made by the very same groups that were interested in joining ISIS.

KS: Just so people understand: so the very people who were calling on the factions to unite and pledge allegiances to ISIS were the very ones who made the mistakes you speak of?

AS: Yes, and they were a large group of people, and around three quarters of them were inclining to pledge allegiance. I swear by god they numbered around five thousand—people who had previously given and sacrificed everything for the revolution. Regardless of affiliation, I hold all the fighters in the highest esteem—but I swear three quarters were willing to pledge.

However, there were certain military leaders who committed grave errors, so I withdrew completely from the whole project and wanted nothing to do with it. I made this absolutely clear. I even told Jabhat al-Nusra, I told Fallaq Homs, I told all of them that I just wanted to work. I discovered, however, that politics had tainted the revolution.

When the legislators arrived, they sought me out to receive my pledge, after being told that I was one of those who had said previously that I wanted to pledge. Abu Dawud and groups from that same project told them that I had changed my mind for my own reasons. So they reported me to an individual from Talbiseh [in Homs Province]. I was told, “The emir is coming to take your allegiance.” I asked, “Where will I be posted?” He said he was in Talbiseh, and to come to Zafaran.

I told him Talbiseh and Zafaran fall right in the middle of the north, why should I be posted there? Where is the work? For example, we should be heading to the east, to Houla [in Hama province], a very large area. You know, to work. Not merely to establish a state in the north and start dictating over people.

So this individual came to me and gave me an ultimatum: either I pledge allegiance or I relinquish my weapon.

KS: Why did he want your weapon?

AS: Because as far as he was concerned I was now a murtad [apostate] for not pledging allegiance to ISIS. The weapon was my own personal weapon, and not issued to me by the organization. I told him I would not pledge or relinquish my weapons.

More importantly, someone had slandered me another way, and accusations of “sahawat” [a pejorative implying cooperation with the US] were circulating. So I was told to pledge. I told him I am a man who doesn’t want to pledge. He said, “Then give me your weapon.” I replied, “If there is someone among you tougher than Abdel Basset, let them come forward and take my weapon. Gather all the men you have and take my weapon. If you are more of a man than Abdel Basset, or if anyone with you is, let them try to take my weapon off me.”

That was my response to them. Think of it like this: if someone is prepared to address them in this manner, then you know immediately that all ties have been severed.

KS: So just make it completely clear, you never pledged allegiance [to the Islamic State]?

AS: Of course not.

KS: On 9 September 2015, your brigade put out a video to deny you pledged allegiance and to make it clear that you were an independent brigade. What was the reason?

AS: The battle in Zafaran and Talbiseh had begun, rebel factions fighting against ISIS. In the middle of this, Jabhat al-Nusra approached me requesting my allegiance. This was in the heat of the battle, and many witnessed this. They came to me; they were afraid of me. These legislators—Sheikh Abu Rashid Al Gahm, Sheikh Hatim, and Sheikh Azzam—asked me what my position was regarding this battle.

I told them we don’t want to get involved. We are a group that refuses to spill the blood of other Muslims, and at any rate if we supported ISIS, we would have pledged allegiance to them. They were very understanding at first: “May god reward you; we know you don’t like bloodshed and you have always been good role models.”

After the battles had ended, I would come and go as if nothing had happened. The battle was over. Within six to eight months, I would work in the eastern areas to support the fronts. I was working independently. As you know, I wasn’t affiliated to any faction and I didn’t have any foreign backing. I started my own brigade. We worked in Hasad; we worked in Zaytouna and Baluz.

Everybody knew this as a fact. Maybe in other areas like in Idlib or Dera’a, they could be ignorant of this. I swear to god that everyone in the Rif knew this, even the group that fought me. All of them are well aware that we established this brigade from our own hard work and sweat; we funded ourselves through war booty on these fronts. We ambushed that pig [regime commander] Suheil Hassan’s men in Salamiyah, capturing Grad rockets and Konkurs [anti-tank guided missiles], and we executed thirteen of them. This is how we provided for ourselves.

I believe this is the real reason they fought me: because we were becoming so much stronger and influential in the area. They eventually started reducing the number of my men on the fronts.

KS: Why were they removing your men? What excuse did they give?

AS: It was certain individuals they targeted. We were apparently committing “crimes,” such as listening to [Islamic State songwriter] Abu Hajar al-Hadrami’s nasheeds. They would take you and place you in re-education, because listening to these songs meant you had sympathies to ISIS.

KS: So this is why you released a video?

AS: Yes, I released a video to set the record straight, and I was very honest and clear; however, today I regret releasing it. I regret it because it gave legitimization to the trial. Really I should have just released a statement from the start and put an end to this whole ordeal.

KS: After you released this video, you were requested to appear before the High Sharia Court of Homs, because Jabhat al-Nusra had accused you of having pledged allegiance to ISIS. What exactly happened during your trial?

AS: If I tell you in detail I will take an incredibly long time. I will give you a curtailed version with just the important parts.

I was summoned by the court, and it brought a jury that would observe my side of the story first. Then they would be invited to another sitting where they would only see Nusra’s side of the story. After hearing both sides independently of the other, both I and Nusra would be summoned to a second hearing where all sides were present.

The jury was made up of a mixture of well-known people from a variety of areas who had previously arbitrated settlements between different factions from Talbiseh and Nasr al-Nahar [in Homs Province]—including, for example, Fallaq Homs.

I sat down and straight away told the court: “So I am being accused of being affiliated to ISIS? Okay, bring the proof.” They didn’t have any evidence. They asked me daft questions like “Do you listen to songs by Abu Hajar al-Hadrami?” These kinds of questions are embarrassing, because everyone in the north listened to his songs. These were merely suspicions, and in Sharia law you cannot base your evidence on suspicions.

I sat down in this hearing to see some evidence. They purposely delayed things in order to talk about suspicions based on some in my group who “give the vibe” that they are affiliated to ISIS because they have long hair, or listen to Abu Hajar al-Hadrami. I asked that Nusra bring all their evidence and accusations forward, and that we all sit down together in court as two parties with witnesses.

But I sat down with the jury for the first hearing without the presence of Nusra, and they too would sit in court without my presence (and without the jury) to put forward their claims. Then, when the trial actually commenced, we were meant to sit down as two opposing parties with evidence brought against me.

But when the trial began, I found myself alone in the court: no Nusra or jury. “Where are my accusers?” I asked. I was waiting for their evidence and accusations, and if I were proven to be an ISIS member I would surrender with my brigade, my weapons, and equipment like I had agreed. I would also have had to make a public apology admitting that I was part of ISIS, and acknowledge that I received a fair trial. I was prepared to solve the whole matter for them.

But I turned up to court and there was no Jabhat al-Nusra. I asked the sheikh, “How come there is no Jabhat al-Nusra?” He replied, “If only Nusra would show up, we could settle this matter. They promised us they would leave you alone, and you also promised the same.”

So we sat down for another hearing—the court had told me they would like this to be resolved, and I wanted it to be resolved quickly as well. We weren’t that unoccupied, to be wasting time like that. We still had Al Wa’er and other areas to worry about. We’re not that unoccupied, to be stopping each other at checkpoints and fighting each other.

So at the final hearing, the jury were present. It was ruled that Abdel Basset is not with ISIS, he just doesn’t want to fight them. I admit I don’t want to fight ISIS, and one of my reasons is that I don’t want to oppress civilians by arresting them on suspicion of them being involved with ISIS, only to find out that they weren’t—similar to how I was framed and oppressed. And some of these people might have children. I am not compelled to oppress people in this way, only to later discover they were just civilians and not affiliated with ISIS.

I told the court I only want to fight the regime; I will fight it to the last drop of blood. They were well aware that I wasn’t affiliated with ISIS. The whole dispute was based on me refusing to fight ISIS, and I have witnesses to confirm this.

Then they told me, “In that case, since there are front lines only manned by your group—if you don’t fight ISIS what will you do when they come from your side? This means that they will eventually enter north Homs.” I told them to bring the military and Sharia councils and to come and observe the front lines and see for themselves. Furthermore, I told them, if the distance between myself and ISIS allows either side to enter one another’s territory, then I hand you the area, my weapons, and myself.

Could I have said anything better than that?

KS: So the court put together a council? Who was part of this council?

AS: It was made up of leaders from all factions: Hajj Bilal from Fallaq Homs; commanders; and a sheikh from the high court. They showed up at Aydoun unannounced and found it completely in ruins. They found both myself and Ahrar al-Sham, which meant I did not have a monopoly over the front, and if I didn’t want to fight ISIS then Ahrar would be prepared to fight ISIS.

Then, when they went to the Dalak front, they found my brigade only forty meters away from Ajnad al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra—three different factions in Dalak. They also found that in the space between myself and ISIS were more than forty villages that were controlled by the regime. There was Salamiyah and many checkpoints—a large distance between us.

KS: So the council presented its findings to the court that it is impossible for ISIS to enter this area?

AS: Yes, and I have witnesses.

KS: However, despite this the court ordered that you and your fighters leave your fronts and fight in a different area, and even convicted you of having pledged allegiance to ISIS. How do you respond to this decision? Why did they ask you to change your fronts, despite admitting it was impossible for ISIS to enter through your area?

AS: This was the crime. I refused to be moved, because my whole brigade was made up of locals that defended their villages first and foremost (and then would defend other villages secondarily). If I left these areas I wouldn’t have anyone to support me—nor do I have foreign backing. The war booty was just about sufficient for us, our whole inventory is made up of arms we captured.

These fighters were local. If I were to go thirty kilometers away with just five of my fighters, my whole brigade would fall apart. That would mean you have killed me. So I outright refused, on the principle that the council had found I wasn’t affiliated to ISIS and neither could ISIS enter from my front. This was in front of a council that had more than forty witnesses.

I asked, “Hajj Bilal, what were the findings of your council?” He replied, “It’s impossible for ISIS to enter from where you are posted, nor do you have a monopoly over those areas”

KS: So why did they announce that you were convicted of pledging allegiance to ISIS?

AS: Because I had rejected their judgment. Today these courts unify all the brigades, and they have to form a consensus. This is the real battle—not whether I was an ISIS member. My battle was that the high court represents all the factions, but is dominated by Ahrar al-Sham on one side and Jabhat al-Nusra on the other. If I refuse their judgment and they’re not able to implement their order on me, they will look incompetent.

Both Ahrar Al Sham and Nusra are in competition to show up the other—now why should I and my brigade fall victim to their competition?

* * *

V: Inter-factional Battles

KS: This leads me to my next question. Very shortly after your disagreement and refusal of the court’s decision, a battle broke out with your brigade and Jabhat al-Nusra because they had captured a group of your men from Shuhada Bayada brigade. Nusra later announced that two of those captured were ISIS fighters. Tell us how this incident began, and how it escalated, with your brigade becoming a target.

AS: Firstly, we did not start the fight which caused Nusra to retaliate. The high court—which I am sorry to have even participated in—ordered that no faction or individual has a right to capture fighters from another brigade without written permission from the high court. It also allowed for self-defense if anyone transgressed those bounds. This documentation is for all to see. So I personally was behaving lawfully under Sharia to defend myself.

KS: So what happened? Nusra captured these men?

AS: No, they did not “capture” them. They kidnapped the military commander of Shuhada Bayada, who is my relative, who fights every day in the path of god, as well as my cousin Nizar Sarout.

After they kidnapped them, they told all the factions they had discovered silencers and targets in their possession, and instructions from ISIS. They would go to Sheikh Azzam and tell him they discovered a hit list with his name on it. They would go to Ahmed al-Durzi and tell him, “Abdel Basset has your name on a hit list.” They presented all this information to the court, which would later release its verdict—a big error—that Abdel Basset’s Brigade is involved with ISIS.

Of course they [Nusra] had started it by setting up checkpoints in Zaytouna which flanked my forces on all sides, which led to clashes. I admit I fired on them. They encircled me, and I fired at them. I did not go and attack them. I stayed in my area, and they encircled me after they removed my commanders. If they are going to remove my men and commanders every day, then we have nothing left, and I have a right to fight back.

KS: How many were killed from your side?

AS: Eight brothers.

KS: In this single dispute?

AS: In this dispute two, but in the ensuing battles six more. And not a single one from Jabhat al-Nusra was killed.

KS: We can return to this later; we have gone into too much detail for the viewers.

Some time later, Jabhat al-Nusra attacked an office in al-Ghantu village that was harboring six men from Shuhada Bayada Brigade, and all six were killed. Why did Jabhat al-Nusra attack this office in this safe village, even though it did not have the authority from the court?

Had this dispute between you and them turned into a personal one?

AS: If it were personal, it would have been a lighter situation. It would actually have been cute. However, it was worse than that. This was defiance between us, and a tit-for-tat. By any means, they had to prove I was with ISIS because if it turned out I wasn’t, it would be a calamity. It would make them criminals.

You didn’t let me finish what I was saying before, which was far more important. The moment when the factions had captured me, I swear by god, I swear by god, I swear by god if I had wanted to slaughter them I could have killed no less than 150 of them and swam in their blood. I swear by god, I didn’t back down for the commanders’ sakes but for the soldiers from all the factions whom I respect.

KS: So you refused to fight them?

AS: I swear by god we defended ourselves, and withdrew, and were handed over to the joint army despite having the power necessary to retaliate.

Ahrar al-Sham and Jabhat al-Nusra and all the factions know how steadfast we are in the face of the regime when it is attacking us with ground forces and jets. Despite all attacks, we still hold our ground. I swear by god I was scared for their lives more than my own when they attacked us.

KS: After your brigade had no more presence in the Rif of North Homs, the court carried on trying to prove your allegiance to ISIS. It even released a video entitled “Tibyan Al Haqiqa” which incorporated images, WhatsApp screenshots, and Skype communication to prove your pledge of allegiance to ISIS. Why is the court even now still pursuing this matter to establish proof of your allegiance?

AS: [Mockingly] To prove to the people that I am innocent.

KS: How so?

AS: Have you ever heard of a trial where it would take six to seven months after the conviction to start producing evidence that Abdel Basset is affiliated with ISIS and he is a criminal? In that case, why did you fight me? By god, the factions have now been incriminated in my attempted murder because Nusra told them I had silencers and hit lists from ISIS.

However, they release a video of one of their commanders saying I was going to get silencers and hit lists—notice the nuance on “was.” From the moment they shed blood, they were incriminated and they would have to prove I was part of ISIS, because if I wasn’t it would make them all criminals. I am only a small faction whereas they have organizations and backing and they have the eastern area, which is a beautiful geographical area.

KS: Now in front of the millions of Syrians who will witness this interview, what do you say to them? Did Abdel Basset pledge allegiance to ISIS, yes or no?

AS: My friend, right now I am in Turkey and not in Raqqa [the center of ISIS in Syria].

* * *

VI: Back to the Roots

KS: Tell me about the most beautiful moments of the revolution that you lived. What were the most beautiful moments you witnessed?

AS: A protest would erupt with forty thousand protesters with one voice and one spirit in complete unison.

KS: Where do you see the Syrian revolution at this stage?

AS: Personally, I as an individual am out of the revolution. But I am the son of the revolution.

KS: What do you mean by “out of the revolution”?

AS: As in: I am not in the land of our nation, I am outside of Syria. By god, these days only remind me of the start of the revolution. These were the best days of the revolution.

See these people who are going out and protesting? They will once again go out against Bashar [al-Assad], corruption, oppression, Russia, Iran, and all the nations of the world. This nation will never submit again. This matter has already been decided. We’re already victorious; we can’t be defeated.

These coming days, I believe we are witnessing the tipping point of victory. By god, this is the peak of victory. I am not reminded by anything except the beginning of the revolution.

KS: Before the interview, you told me you had new songs which you will sing for us for the first time. If you could, please sing for us.

AS: Before I do, I just want to apologize if I have defamed any of the fighters. I send out this message to every fighter and every faction: I wasn’t generalizing about Jabhat al-Nusra nor any other faction. I was speaking about some emirs in Jabhat al-Nusra in the north who believed I had taken some of them prisoner in Sednaya. I did not imprison them, by god it was the regime that had imprisoned them.

The fighters in Jabhat al-Nusra or Ahrar or Fallaq Homs—all factions, even if they fought me, I forgive them all because they fought me under orders. The fighters are a crown on my head and I hope they don’t think that I was attacking them.

I dedicate this song to all the Syrian people as a whole. This song also reflects my recent ordeals. It’s entitled “This Nation.”

[Singing] This nation with our souls; This nation, its blood flows in our veins; This nation loves Uthman and al-Farouq; We remain dismayed, and brothers become disunited; My Lord most high, have mercy and give victory to the downtrodden nation.

The oppression we will never forget, and victory is coming with drums beating; Keep patient, oh Dera’a, we have laid down our lives for you. Don’t forget us; Have pity on us; Your victory is in our hearts.

The dogs of betrayal are propping the powerful on their seats; They were the ones that brought hardships upon this nation. Greetings to Idlib and Horan, we need your men. At times I am hungry, and at times I have tears, but I am always proud; As oppression and calamities increase, the flags of tawhid [unity of God] will keep waving over the lands of the Sham [Levant].

Whoever transgresses on your land, Syria, will die on your land.

I am Homs, I dream every moment that I see you; Oh Homs, I promise that forever I will never desert you. Madaya got aid but when will Homs get aid? They betrayed it and fed Fu’ah [a regime enclave in Idlib Province] and starved all Homs’ people.

This nation the land of the Levant, its people have never been sahawat, nor murtad; This nation is the one that began this revolution, and it will end it and be victorious.

Featured image: Abdel Basset al-Sarout leading a “Worldwide Red” protest in exile in Istanbul during the diasporic Syrian-led global #AleppoIsBurning campaign, 1 May 2016. Source: @AleppoIsBurning (Twitter). All other images and videos via EA Worldview.

Lightly edited by Antidote for readability.