AntiNote: Since the publication of this article in German, there have been additional developments that have kept the Austrian extreme right in the headlines. It turns out that the Christchurch shooter and Austrian identitarian Martin Sellner were not only in touch remotely and financially but may also have met in person. Also, the institutional extreme right there, embodied by the Freedom Party of Austria (Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs, or FPÖ), founded after World War Two by literal Nazis and part of Austria’s governing coalition since October 2017, has collapsed in disgrace—bringing the government with it—after revelations of attempted backdoor dealings with Russian oligarchs. Make of that what you will.

The Balkans in Rightwing Mythology

by Adnan Delalić and Patricia Zhubi for Die Wochenzeitung (Switzerland)

11 April 2019 (original post in German)

Racist memes, nationalist myths, and crude conspiracy theories: within the ideology of the New Right, southeastern Europe appears as a transitional space where the future of the West is being decided.

Investigations into the 15 March 2019 Christchurch attack took on an international dimension ten days later when federal security and intelligence agents searched Martin Sellner’s apartment in Austria under orders from the prosecutor’s office there. Sellner is a leading functionary of the Austrian Identitarian Movement (Identitäre Bewegung Österreich, or IBÖ). He came under the authorities’ scrutiny because of a €1,500 donation he had received from the Christchurch shooter in January 2018.

After the search, Sellner portrayed himself on YouTube as a victim of state repression. While politicians and commentators argue about the nature of the IBÖ, its members organize demonstrations and solidarity actions and drum up social media and financial support from around the world. A donation does not make Sellner an accomplice to a massacre—but there are ideological bridges that connect the Identitarian Movement (also known as Generation Identity) as well as other extreme rightwing groups to the Christchurch mass-murderer.

Undesirable Foreign Foods

Attempts to distinguish the IBÖ from “ordinary” rightwing radicalism are specious not only because Sellner, according to media reports, used to paste swastikas on synagogues in his youth; beyond that, he belonged to the social circle around Austrian Holocaust denier Gottfried Küssel, whose blog Alpen-Donau.info was removed from the internet by the Austrian interior ministry in 2011. This kind of increased legal and police pressure led to the founding of the IBÖ a year later, which attempts (in the tradition of Alain de Benoist, an early progenitor of the New Right) to replace völkisch-nationalist vocabulary with terms carrying less historical baggage—terms like “identity.”

In a YouTube vlog from early 2015, Sellner posed—with hipster glasses and a sharp part in his hair—in front of a food stand menu offering burgers, hotdogs, and Bosna sausages. His goal: to educate his viewers about Austrian cuisine and undesirable foreign foods. Austrians! Do not eat at McDonald’s—and certainly not at kebab stands, the epitome of “multicultural capitalist mania”! In this online broadcast, Sellner sells the message additionally with his choice of t-shirt (available at his online store…). Upon it are the words “Restore Europe, Remove Kebab, Restore Empire.” Precisely this reference, “Kebab Remover”—a racist internet meme endorsing the genocide of Bosnian Muslims—was on display both on the Christchurch terrorist’s weapon as well as in his manifesto. Sellner has also cracked wise on Twitter about being in “Remove Kebab Mode.”

The Christchurch shooter referred to the Balkans in other ways as well. On the way to committing his act of terror, he listened to a song honoring the Serbian war criminal Radovan Karadžić, who would only a few days later be sentenced to life in prison at the Hague. In addition, the shooter is alleged to have traveled to several countries in the Balkan region in order to visit the sites of historic battles. The engravings on his weapons with the names of figures from Serbian, Montenegrin, Polish, and Spanish history also point to a deep fascination with struggles against the Ottoman empire. Southeastern Europe, in the imagination of the New Right, is a kind of transitional space where Christianity and Islam clash.

This motif is not new, and has many variants, alternately glorifying the Spanish Reconquista, the defense of Vienna, or the Russian-Ottoman wars. Karadžić referred to the genocide at Srebrenica as “just and holy”—in his view, his troops had prevented the establishment of an Islamist caliphate. The Norwegian rightwing terrorist Anders Breivik, in turn, called Karadžić an “honourable Crusader and a European war hero.” Occasionally, the motif appears in reference to a supposed transnational Muslim conspiracy against the Christian West, in which Serbia is presented as the bulwark against a neo-Ottoman invasion of Europe. The Christchurch shooter referred to Kosovar Albanians as “Islamic occupiers.”

An Appealing Trope

There are other points of contact. The Christchurch shooter’s manifesto was titled “The Great Replacement”—clearly named after the racist conspiracy theory popularized by Renaud Camus, an ideological godfather of the New Right in France. In his imagination, Europe’s white, Christian population is being systematically replaced by predominantly Muslim “invaders” from Africa and the Middle East. There are many variations on this demographic panic. It is the glue that holds the Fascist International together.

It can be observed as a central motif in the Greater Serbia ideology of Radovan Karadžić, which purports that Bosnian and Kosovar Muslims are secretly pursuing a “demographic jihad.” In the SANU [Serbian Academy of Science and Arts] Memorandum of 1986, a milestone of Serbian nationalism, it is claimed that the high birthrate of (predominantly Muslim) Kosovar Albanians is a central component of their drive for an ethnically pure Kosovo. The former Bosnian-Serb general Ratko Mladić justified war crimes against Bosnian Muslims with the claim that the Islamic world possesses, if not an atomic bomb, then a “demographic bomb.” Breivik, for his part, refers to this as an “indirect genocide.”

The obsession with birthrates and these paranoid theories of intentional displacement and replacement do not necessarily lead to violence—but they do mentally prepare their proponents for it.

The Islamophobia inherent to the ideology of Greater Serbia, in which traditional and contemporary motifs are bound together, is emerging in the globalized context as an appealing trope for the Fascist International. The specter of multiculturalism can only be overcome with a fundamental reordering of space along ethnic dividing lines that faded out of relevance long ago. The aim of this “racism without races” is the establishment of ethnically homogeneous societies, side by side but separate.

In September 2018, Sellner took part in a torchlight march “in honor of the heroes and saints of 1683.” In this case, Vienna symbolized the bulwark against past and future Islamic invasions. “I don’t get how there can be people from the Balkans who spit in the faces of their forefathers and their defensive struggle against the Ottomans,” tweeted Sellner in June 2017. So Islam must be fought and defended against—but without violence, apparently: “Rightwing terrorism is, like all other kinds of terrorism, to be morally rejected,” announced the leading identitarian figure immediately after the Christchurch attack. How this is supposed to work, when—judging from slogans like “Stop the Great Replacement!”—the Ottoman army is already pounding at the gates, is unclear. War symbolism and fear-mongering only fit into the self-conception of the “moderate migration critic” when rhetorical fear-mongering can be cleanly separated from real terrorism.

No matter how much Renaud Camus and Martin Sellner try to distance themselves from the terror attack in Christchurch, the insistence of the IBÖ that it is not a radical rightwing movement is simply untenable. The fight against this ostensible “replacement” and the IBÖ’s concomitant declaration of war on multicultural society are not “moderate” positions. The claim that coexistence is impossible is not meant merely as a description of conditions but rather as a goal. For Karadžić it was not only about the fight against Islam. Tolerance and the multicultural character of Bosnia were also to be erased and made impossible for generations to come.

Ideological Cocktail

The ideas that became socially acceptable with the rise of Serbian nationalism in the 1980s soon found their concrete political implementation. What emerged was an ideological cocktail of racism, demographic panic, conspiratorial paranoia, and revanchism that ultimately proposed an urgent need for action against an allegedly existential threat. The destruction of the Other became necessary to ensure Our survival. Karadžić still argues to this day that he was acting defensively against a “toxic, all-destructive Islamic octopus.”

It is not particularly surprising that paranoia about demographic “invaders” also takes an antisemitic shape. The Serbian nationalist cult director Emir Kusturica, for example, is among those who pin the blame for the “refugee crisis” on the Jewish American billionaire George Soros. According to social theorist Moishe Postone, modern antisemitism is not merely a form of racism, but at the same time a way of explaining the world which promises mistaken paths out of one’s misfortune. We can understand conspiracy theories like “the great replacement,” which declare as enemies both the weakest among us as well as global elites, in a similar manner. Islam and Judaism overlap as bogeymen, as both sublate the particularity of individual nationalisms. Unity is imperative in fighting the great enemy.

Karadžić’s ideology is neither unique to the Balkans nor the result of “centuries-old blood feuds.” It also is not a genuinely Serbian phenomenon. Rightwing radicalism does not have a country of origin; it derives inspiration from everywhere. The ideological store of the Fascist International feeds on various traditions and regions. What has evolved is a globally available repertoire of nationalist myths, symbols, and tactics to choose from. Events in Bosnia and Kosovo show what kinds of consequences such ideas can bring—and not just there.

Berlin historian Patricia Zhubi studies the past and present of antisemitism and the transnational structures of the radical right. Bosnian-German sociologist Adnan Delalić does research on Islamophobia and genocide, among other things.

Translated by Antidote and printed with the kind permission and help of the authors.

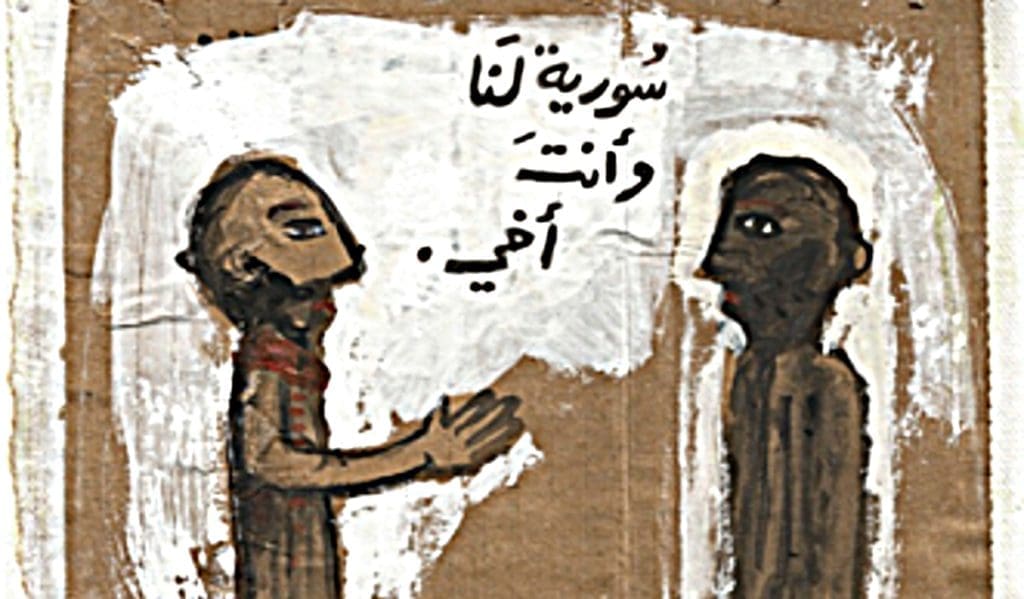

Featured image: artwork by Bosnian-American Samir Biscevic displayed at a ten-year commemoration of Srebrenica at UN headquarters in New York in 2005.