Torture, Tears, and Desperation in Mexico’s Migrant Jails

By Movimiento Migrante Mesoamericano

27 June 2019 (original posts in Spanish and English)

Translated by Scott Campbell and cross-posted at It’s Going Down, Falling Into Incandescence, and El Enemigo Común. Republished with permission.

Lizzi was detained for forty-five days, during which time she says she suffered physical and psychological torture. “The treatment we received the entire time was disgraceful.”

“‘You’re going to die! Sign your deportation and go back to your country!’ was what I heard as I struggled to recover from the asthma attack I suffered in the migrant detention center. I felt cornered by the guard and considered doing it, but remembering the problems that led me to leave my country, I dropped the idea.”

Lizzi is one of 51,607 people detained in Mexico by the National Migration Institute (INM) during the first four months of 2019. She was detained for forty-five days, during which time she says she suffered physical and psychological torture. “We felt like we were in a jail, it was horrible! I had two asthma attacks inside. When we came back from the doctor, another guard asked me, “And you want to ask for refuge? Do you know you’ll be locked up for three to six months?”

A few meters from Pakal’ Ná park, near the train tracks in Palenque where hundreds of migrants meet to share their stories, the young, twenty-year-old mother recalls her painful experience. She left Honduras because she had problems with her son’s father, who belonged to one of the gangs. After years of abuse and threats, one day she decided to flee with her son to the United States to start a new life.

They crossed the border in mid-April at Frontera Corozal, Chiapas, but were detained at the intersection to Palenque. She remembers it was early morning, they were nervous when they were asked for their IDs, and when they didn’t show them, they were forced into an INM vehicle. “They didn’t identify themselves or say if we had any rights, they just put us into the vehicle that took us to the detention center. We were five adults and two children (three men, two women, my six-year-old son, and a baby).”

While her compatriots watched with longing and curiosity at the movements of the train on which they could reach their wildest dreams or suffer their worst nightmares, Lizzi continued her story: “It was traumatic. One compañero who refused to be detained was shoved in by force. They didn’t care that they were doing this in front of children who were crying without understanding what was happening. In that moment, I thought about what would happen to my son and me if they deported us to Honduras.”

In the detention center, other women told her about the possibility of requesting refuge in Mexico. “I asked the immigration agents and they got upset. They just said that the process took three to six months. It wasn’t until a representative from the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR) visited the center and explained it to us that we decided to begin the process.”

From January to April 2019, the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance received 18,365 applications, of which 10,107 were from Hondurans; 2,880 from Salvadorans; 2,464 from Venezuelans; 973 from Guatemalans; 760 from Cubans; 696 from Nicaraguans; and 485 from individuals from other countries.

“The months we were in detention were very torturous,” Lizzi expressed sorrowfully as she continued sharing her experiences. “In the women’s area there were around eighty people: thirty-five women and fifty-one children. But one day there were more than a hundred, in a space with no ventilation, with heat, mosquitoes, lack of water. As well, the food they gave us was cold and sour, so the children couldn’t eat it and got sick, with the most serious ones being hospitalized.”

These conditions caused the baby that was detained with her to get sick. “We were really worried and called to the guards but they ignored us, saying they’d pass along the report. One day the girl started vomiting at six in the morning and even though she was emaciated, they made us wait until seven p.m. for someone who was already coming to see to a pregnant woman experiencing complications. Then they saw the little one was dehydrated and decided to take her out to give her an electrolyte solution but later brought her back to her mother without her having seen a doctor.”

The girl’s mother was next to Lizzi and sadly nodded as she patted the back of the constantly coughing baby. “The next day they saw she wasn’t improving and decided to take her to a hospital where a doctor reported that she was in such serious condition that she could die in twenty-four hours if she contracted pneumonia. He gave her a prescription and recommendations that immigration decided to ignore on the grounds that they couldn’t provide the child with a special diet of fruits and vegetables because they didn’t have authorization.”

As of April 22 of this year, 31,982 medical consultations were provided to migrants in Chiapas, 258 for pregnant women, 20,646 electrolyte solutions and 13,894 condoms distributed, and 633 rapid HIV tests administered. This according to statements by sector head José Manuel Cruz Castellanos in a newsletter announcing that the state had a comprehensive care plan allowing for dignified and humane attention to all foreign citizens entering the state. But it doesn’t mention how many patients came from migrant detention centers and in what conditions they arrived in.

During her time in detention they suffered from lack of water. “They started to deny us water. Initially, they gave us four or five large bottles but decreased the quantity without warning us. On one occasion they didn’t bring water until 3pm. The children were crying because they were thirsty and we felt like we were suffocating. We begged the guards but they just screamed at us to shut up. One woman who had saved a little gave it to the children, but there was only enough for each to have one bottle-cap full.”

Lizzi thinks the mistreatment was intended to pressure them to sign their deportation orders. “They rationed the water, only giving us access for half an hour. We had to compete to wash ourselves or drink. Some days we didn’t make it. We talked to the guards to ask for their help but they would just arrogantly reply, “Did you apply for refuge? You have COMAR? Well, put up with it! This is how it’ll be for you the whole time and it hasn’t even started to get hot yet.”

In addition, “the toiletry kit didn’t have menstrual pads, only toothpaste, shampoo, and mild soap that we shared with the children. On one occasion we asked for pads. In response, a guard gave us a diaper that we had to cut into pieces. The food was the same for everyone and when there were a lot of people, it wasn’t enough for everyone. There was never adequate attention given to the children.”

The third day after the girl was taken to the hospital, COMAR’s intervention allowed for them to leave their confinement. “At least fifteen children became ill from the heat that fluctuated around forty degrees (104 degrees Fahrenheit) and from mosquito bites. Most of them had the flu, rashes, and stress. Many days, we mothers didn’t sleep because we were fanning them so they could rest. Sometimes we’d take turns so we could sleep. The treatment we received the entire time was disgraceful.”

Responding to statements from Amnesty International, Luis Raúl González, president of the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH), rejected claims that Mexico’s immigration policy was equivalent to that of the United States. “They are different realities: over there is a discourse of hate that creates xenophobia and racism; here there are serious problems as the policy of the current government is more flexible than the previous government.”

However, during the thirty-seven days that Lizzi was in the migrant detention center, she only saw representatives from the CNDH on one occasion. “Even though we told them about what was happening inside, they just took notes and things remained the same.”

The CNDH, in press release DGC/145/19, published on April 15, requested protective measures for migrants from federal and state authorities in Chiapas due to overcrowding in INM facilities, as well as the slowness of immigration processing at the Rodolfo Robles International Bridge, the Siglo XXI Migrant Detention Center, and the shelter in the municipality of Mapastepec, without mentioning reports from the migrant detention center in Palenque.

Lizzi still dreams of reaching the United States to be with her brother. “Mexico is a beautiful place but I don’t feel good here. People look down on us and I’m alone. I’ve been free for several days and I still dream about what I suffered in the migrant detention center. It was very hard because as a mother it hurt to see the suffering of my son and the children around me. I want this story written for them, so that it’s known what migrants are suffering.”

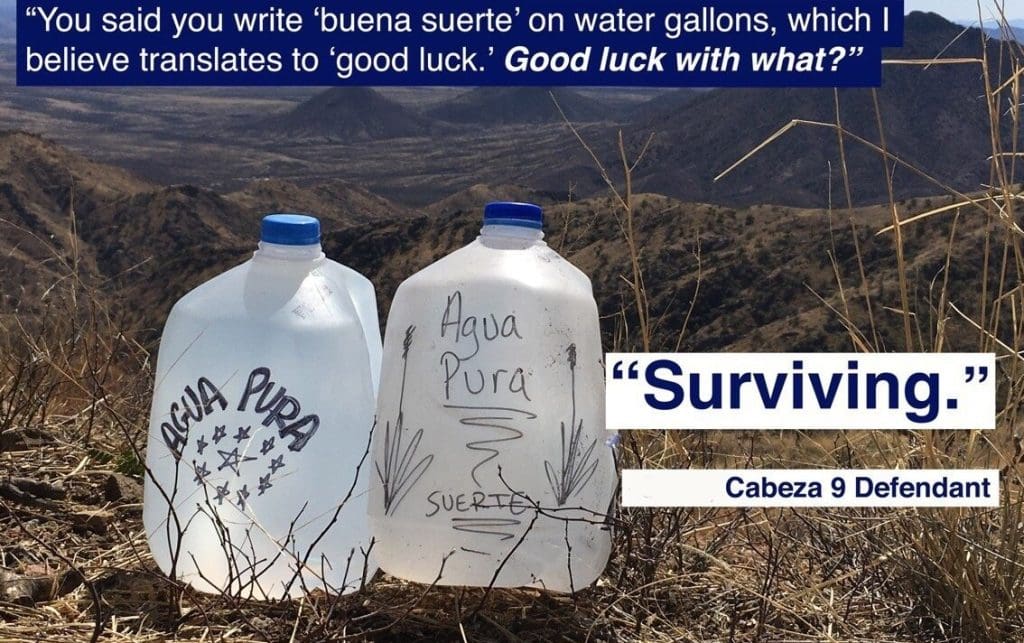

Featured image via Scott Campbell